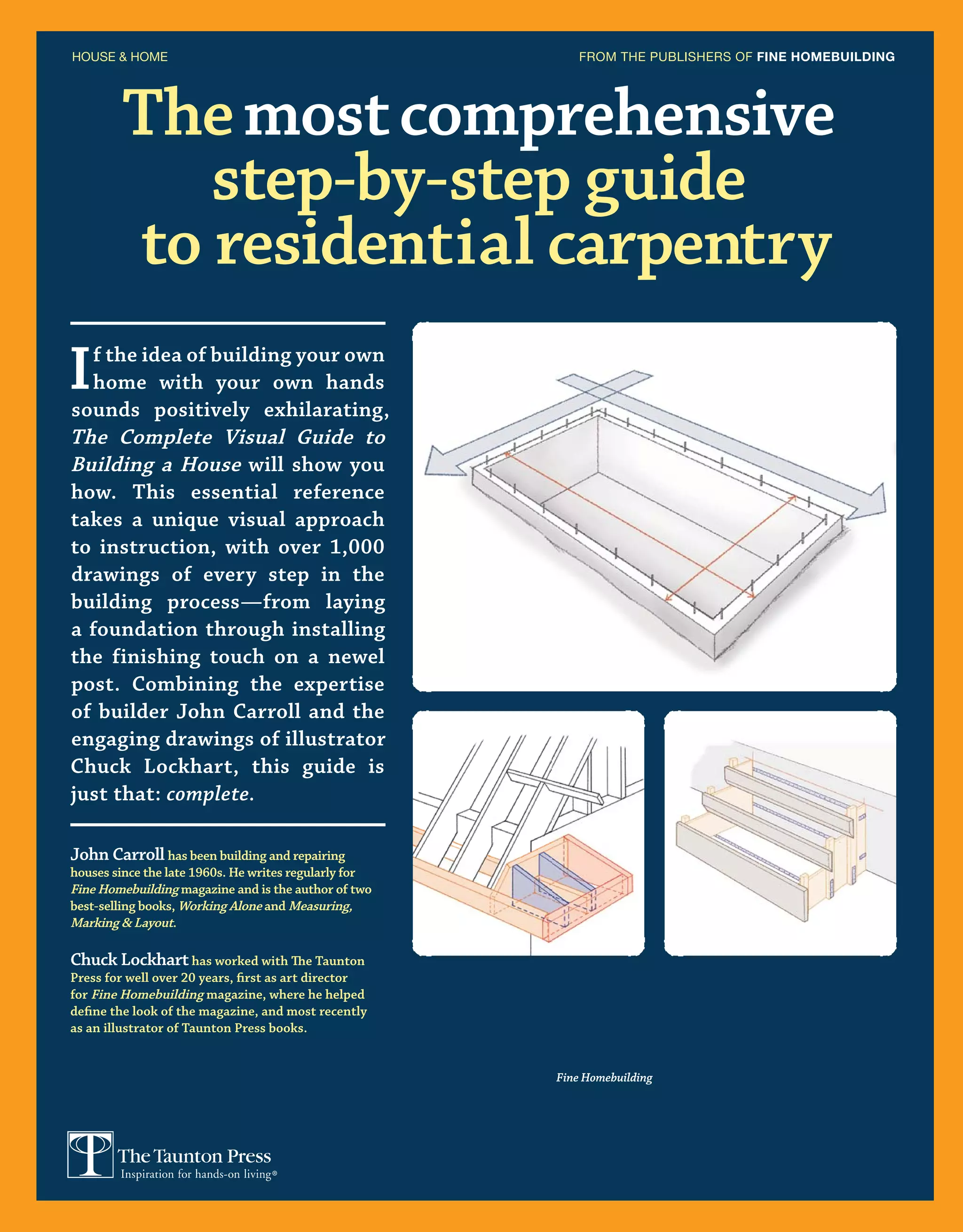

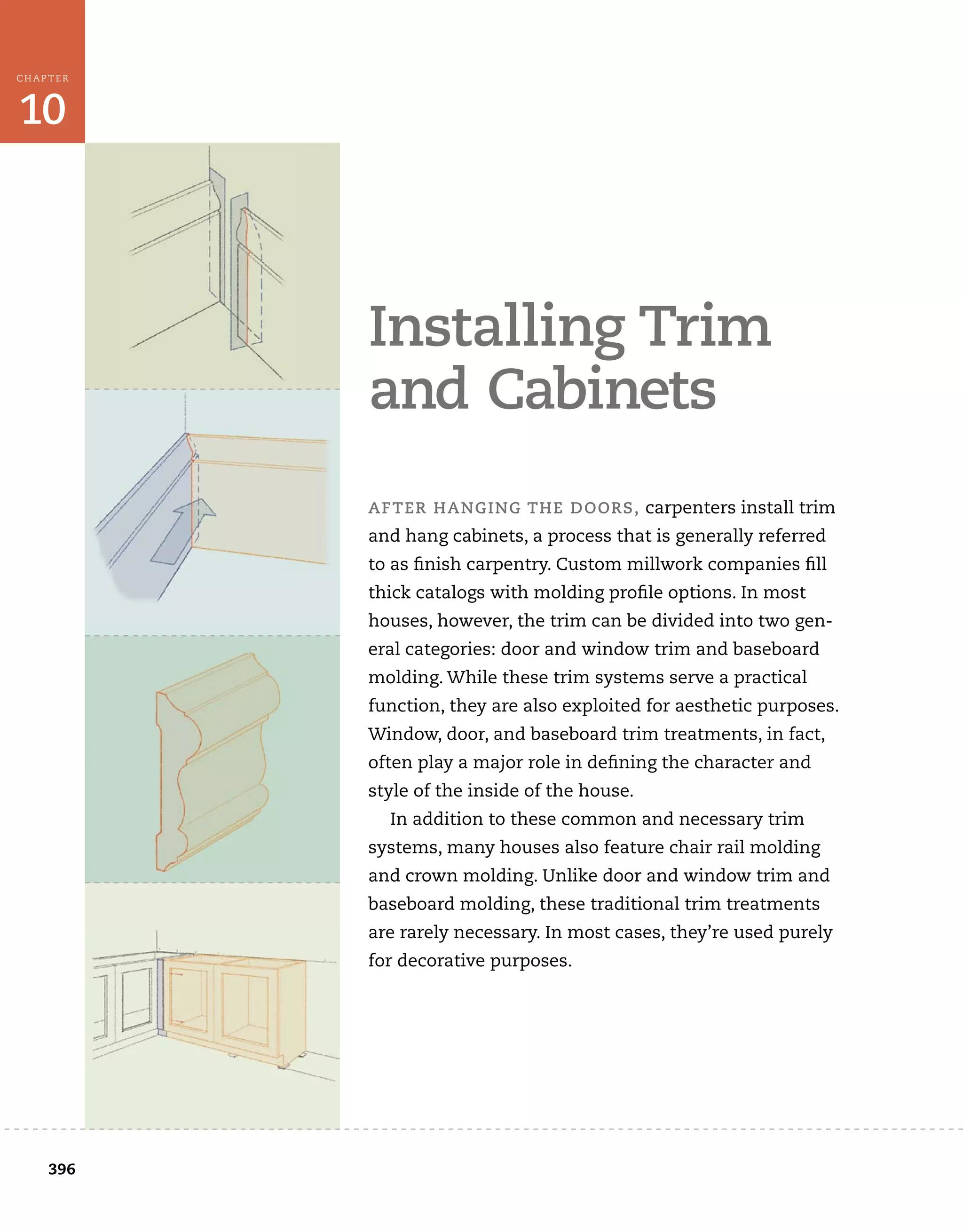

This document provides an introduction to "The Complete Visual Guide to Building a House". It discusses how houses must be built to withstand diverse climates across North America. It also notes that modern homes are expected to maintain comfortable interior environments regardless of outside conditions. The introduction acknowledges the many options in building materials, tools, and systems, and explains that the book will focus primarily on light wood-framed construction since it represents 90% of the housing market. Specific alternative building methods or complex designs are not covered in depth to allow for broader discussion of mainstream construction practices.

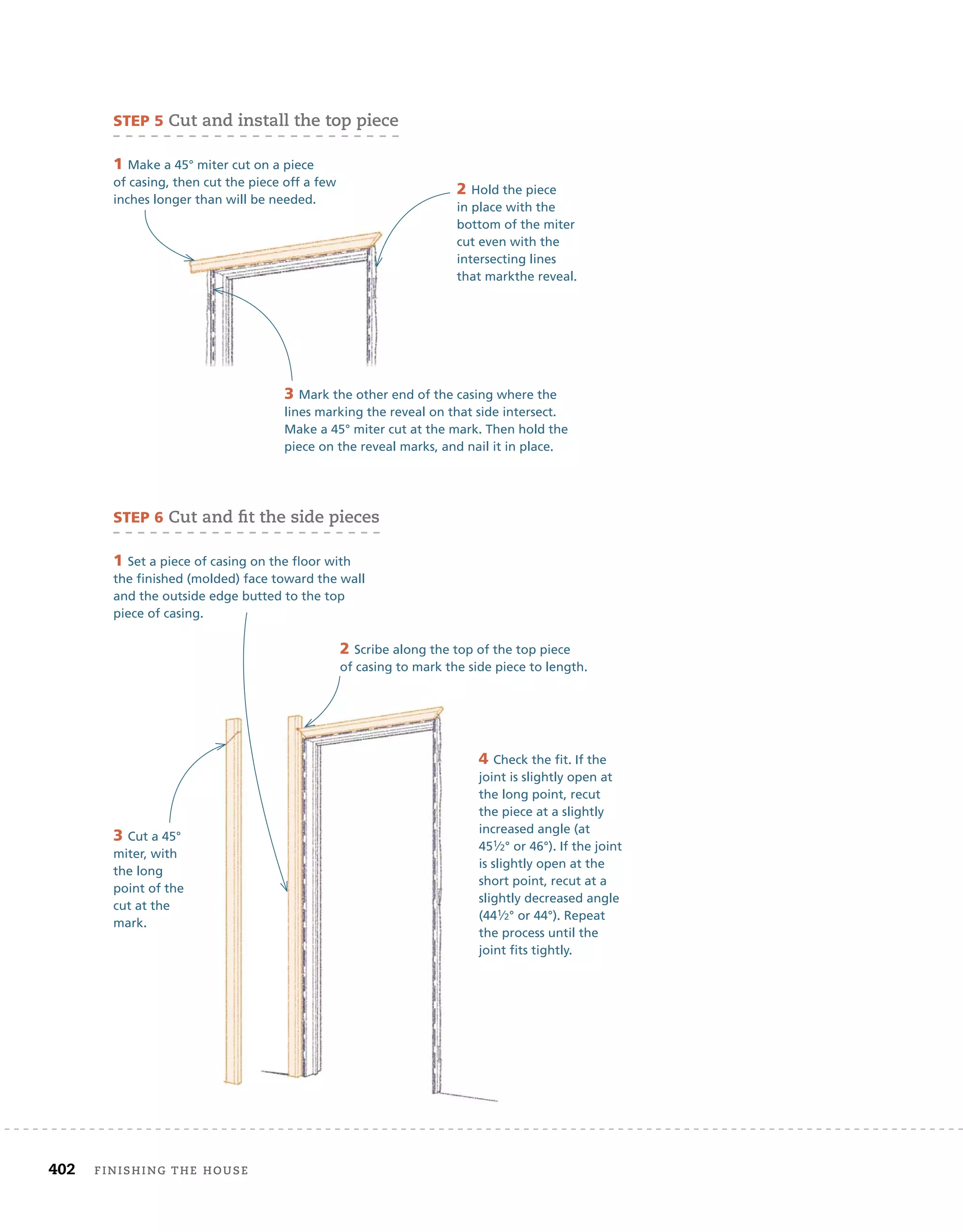

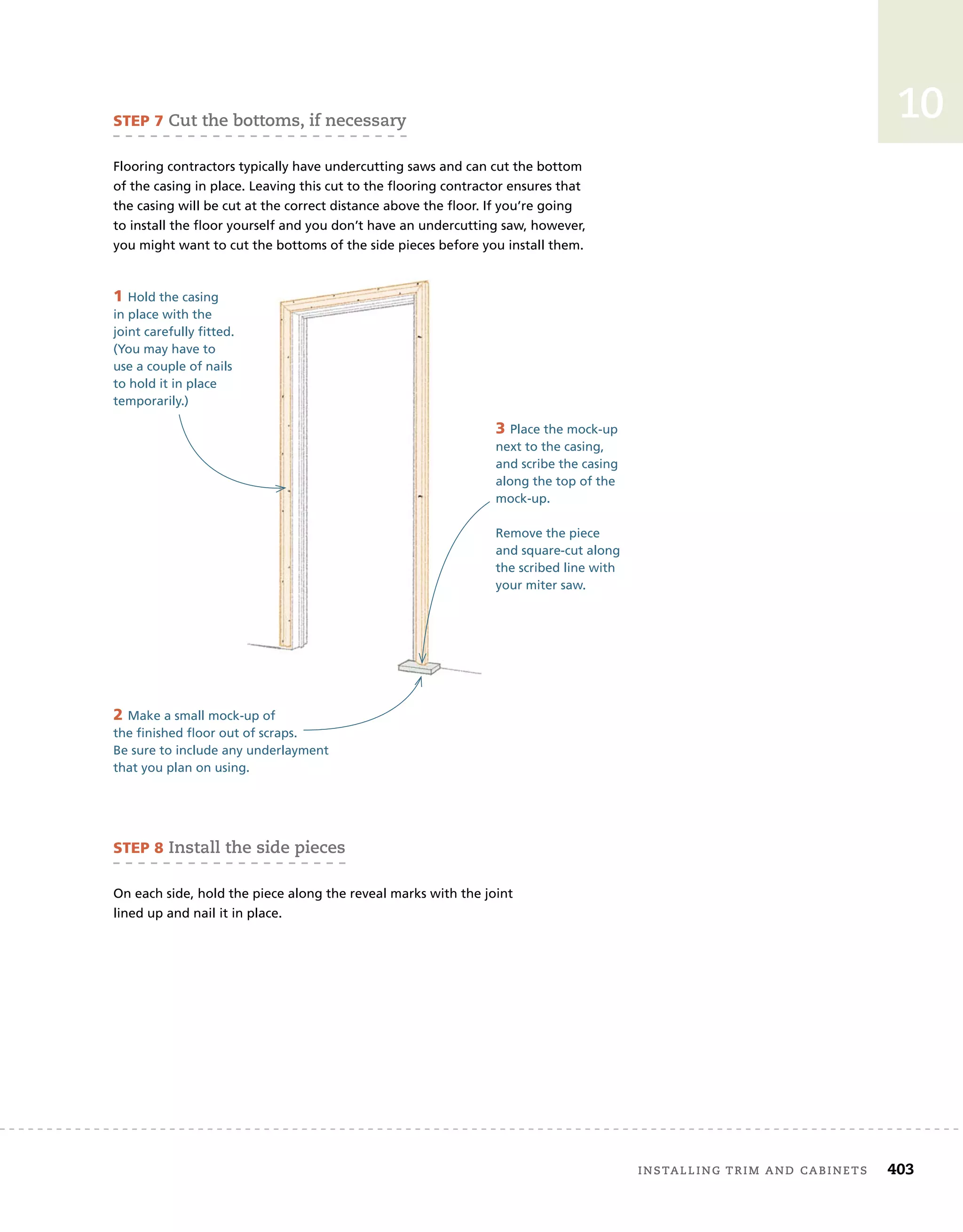

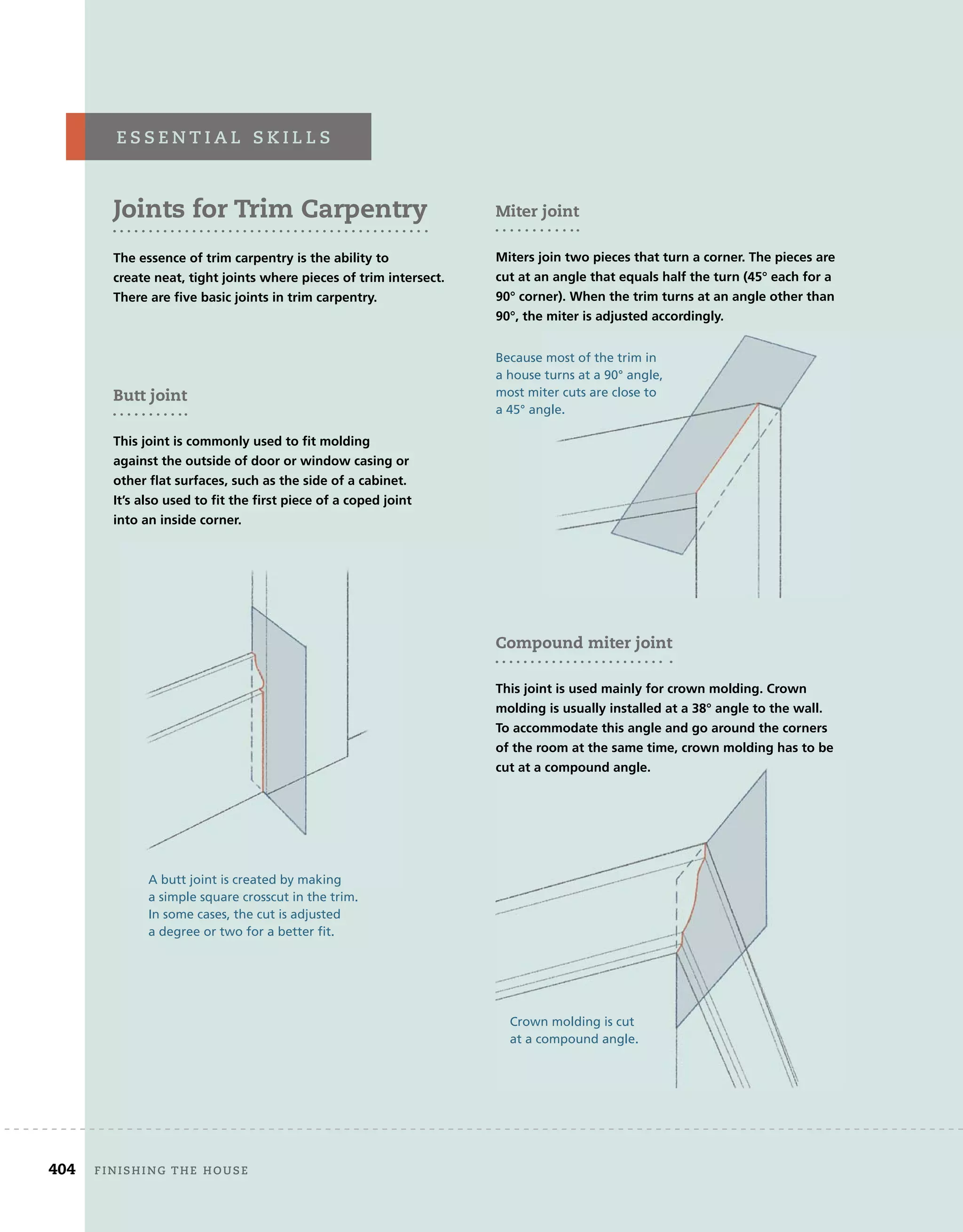

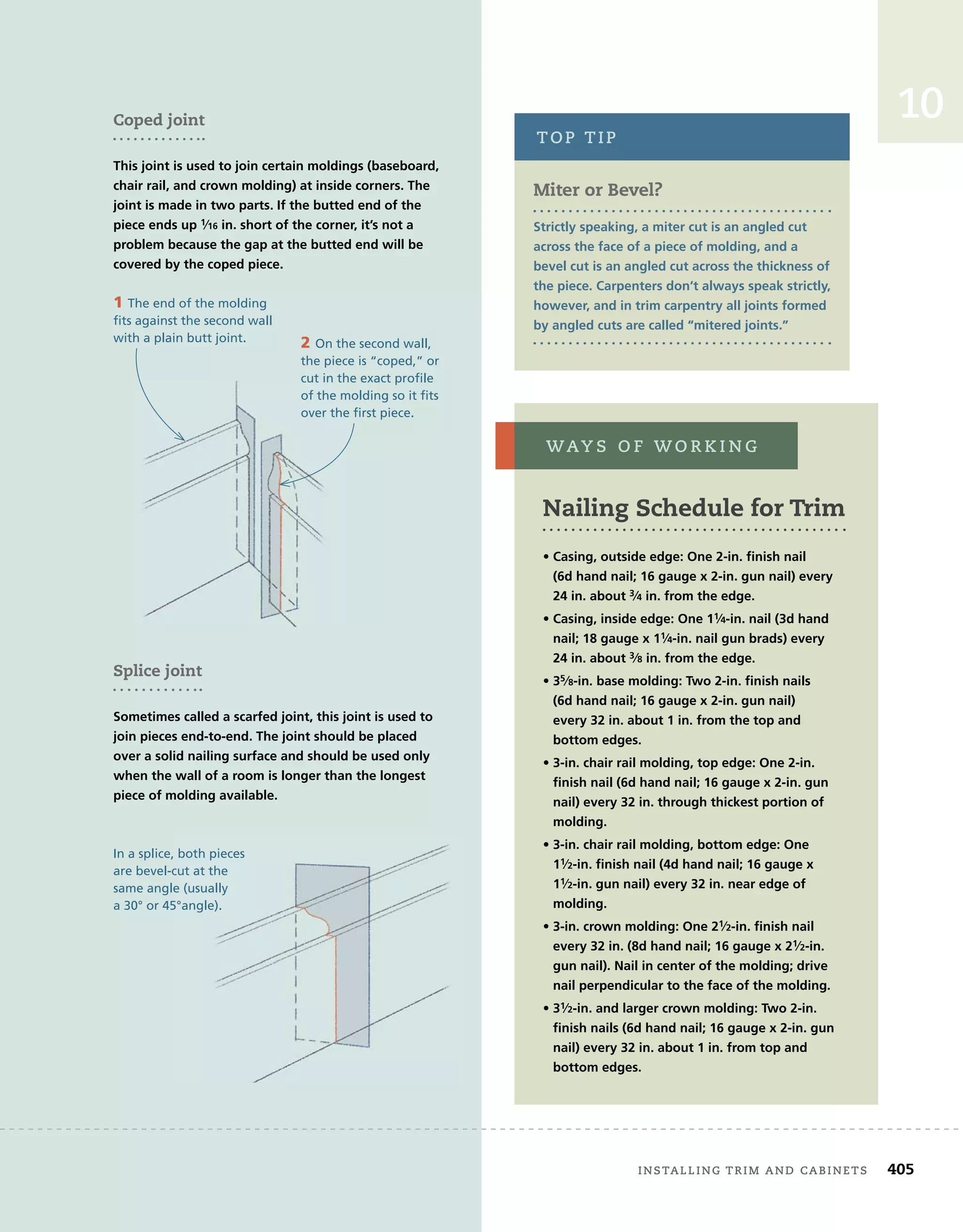

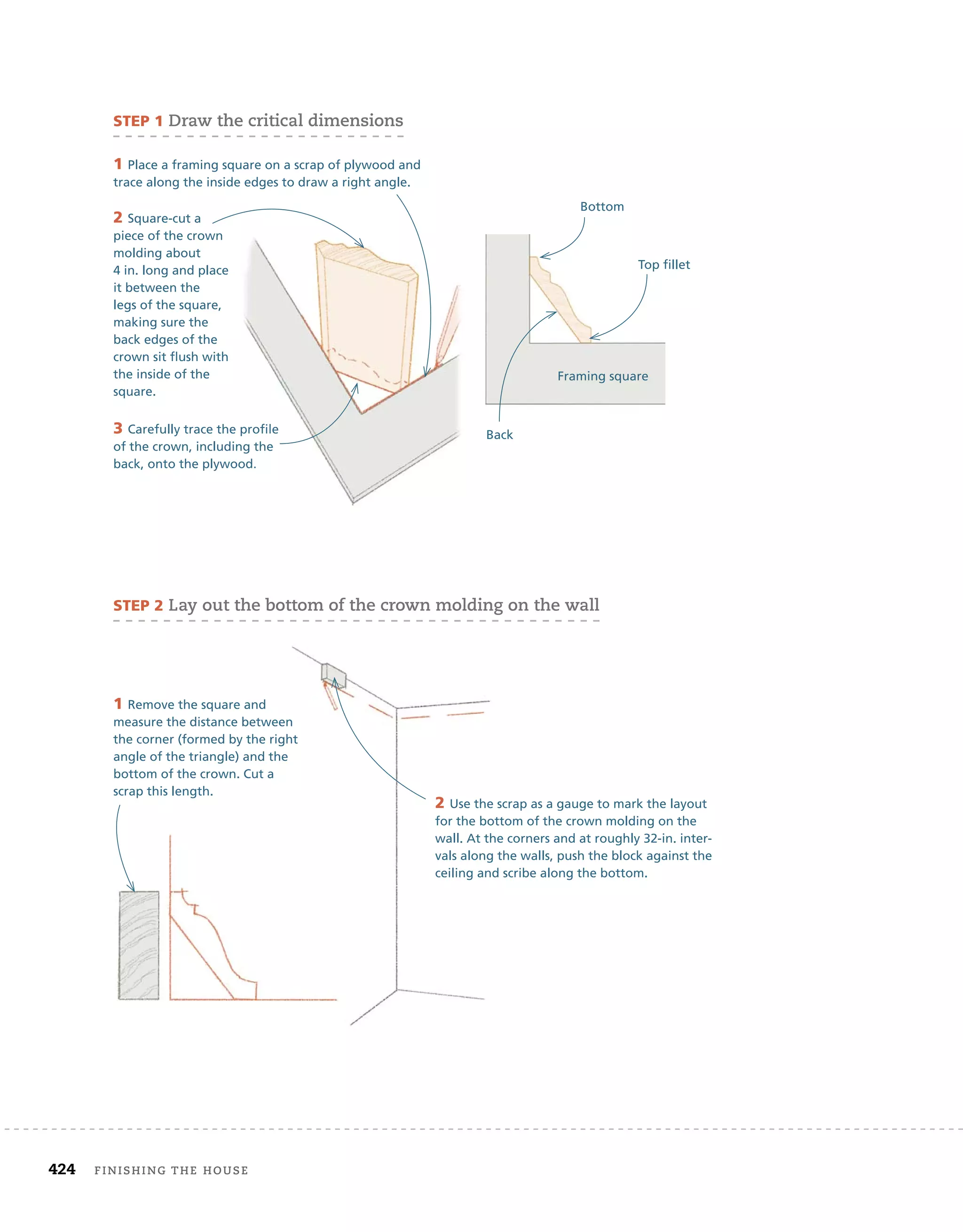

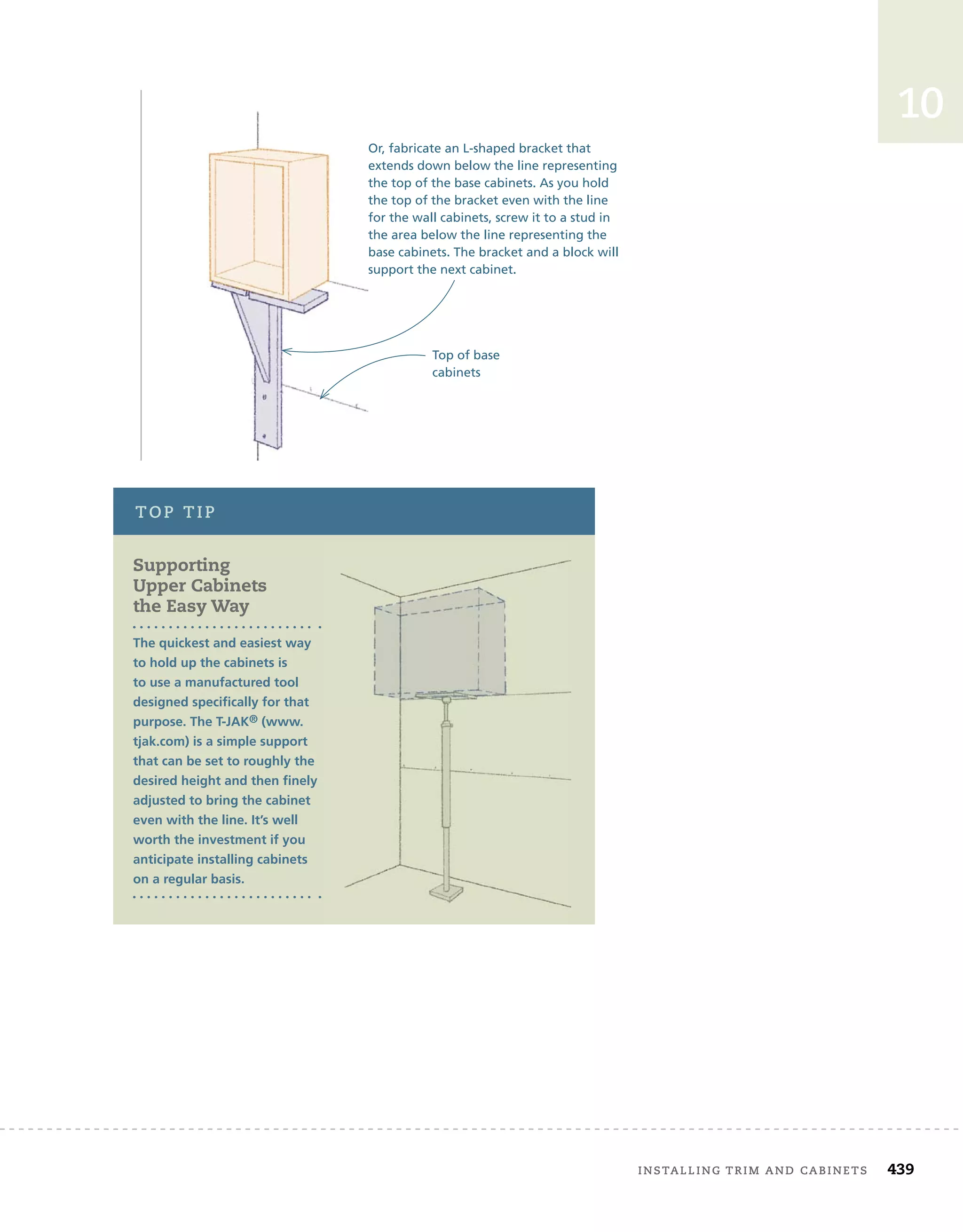

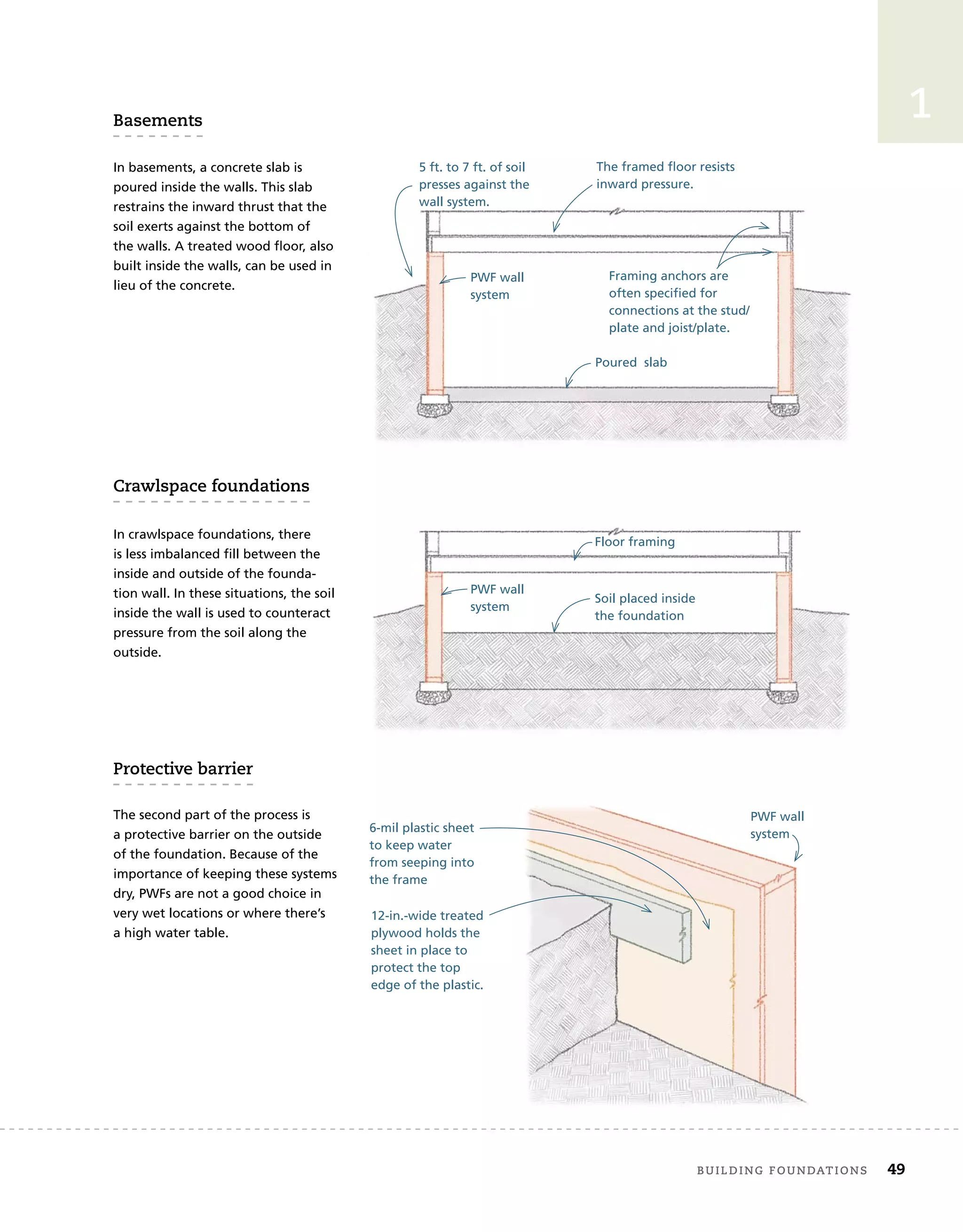

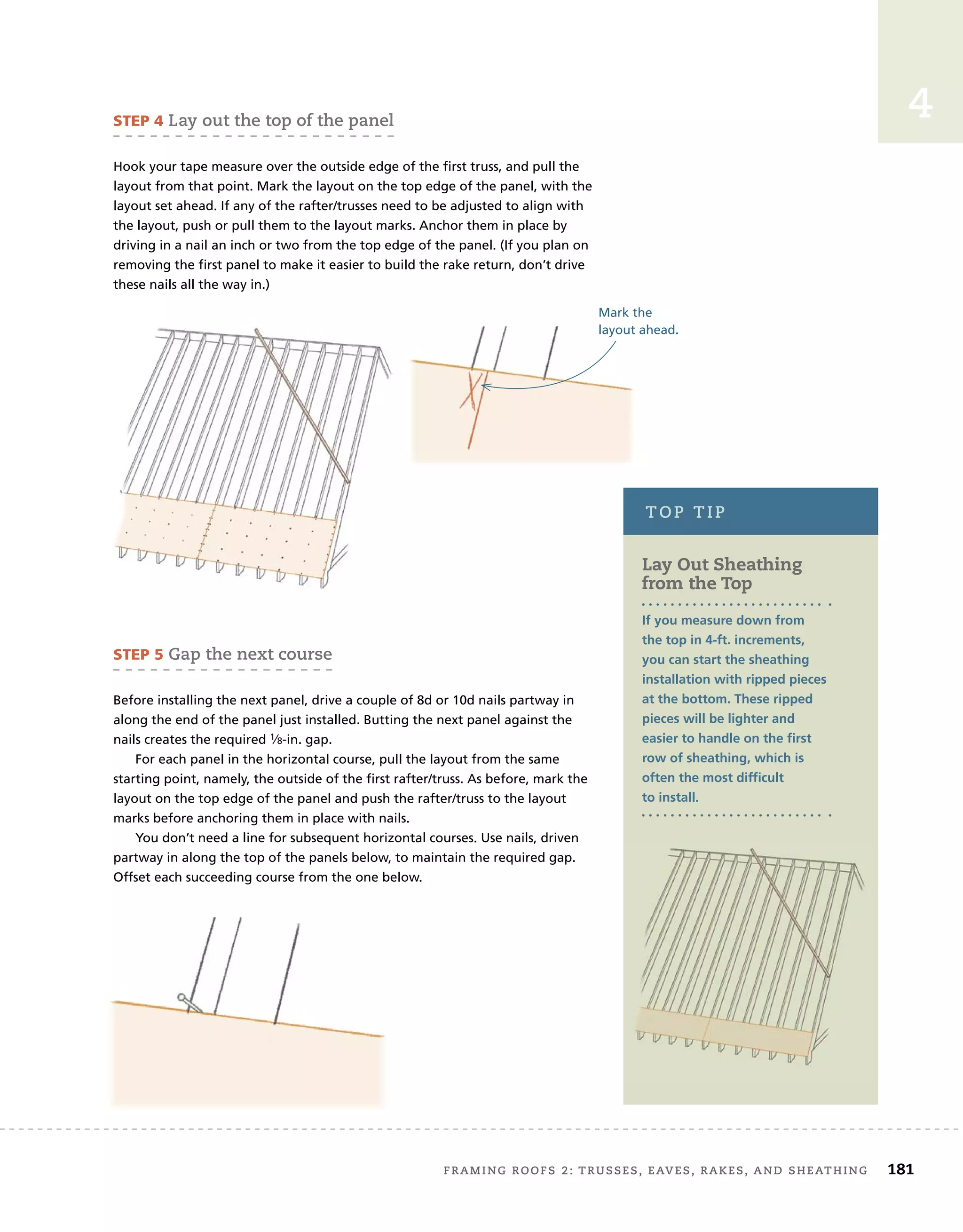

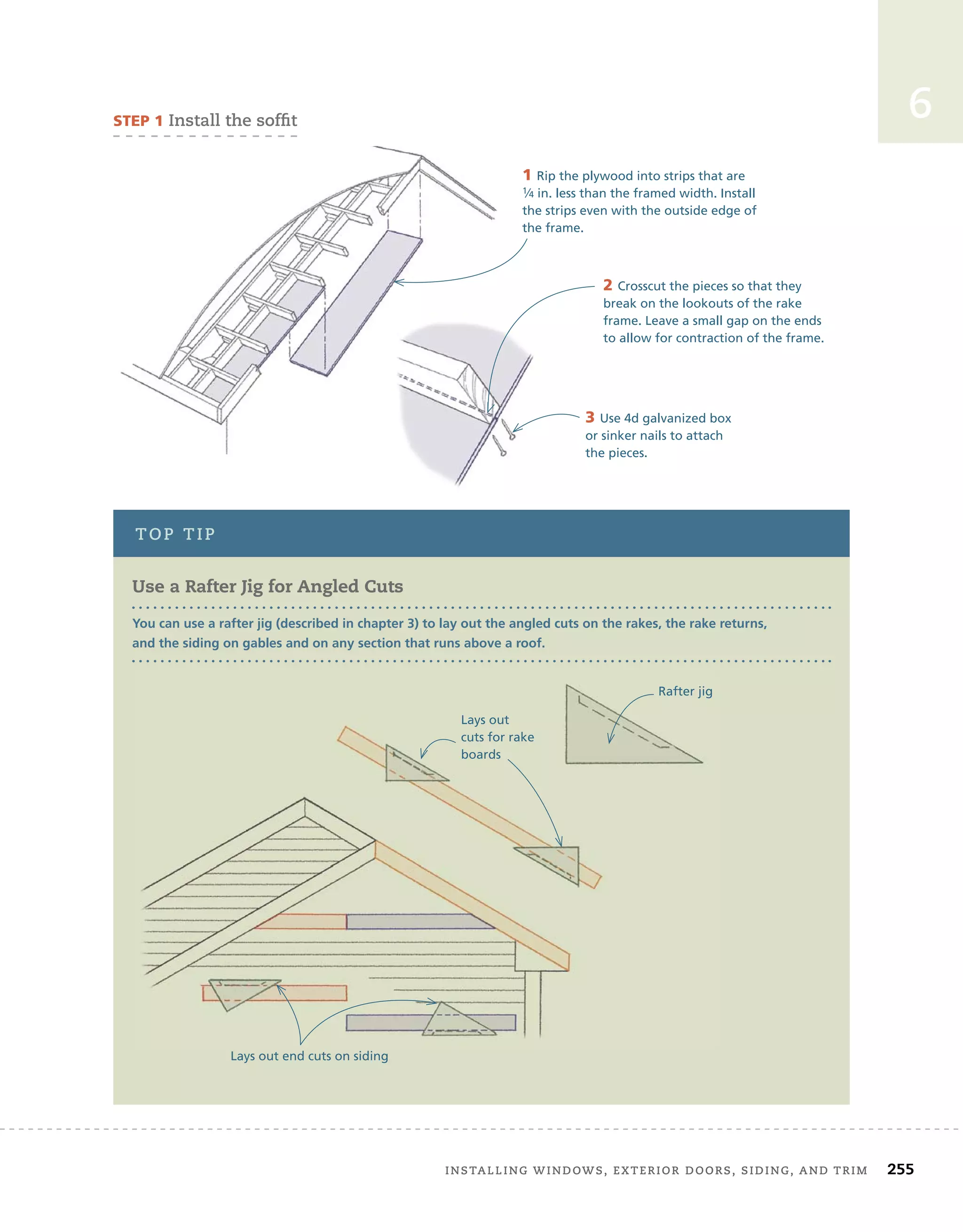

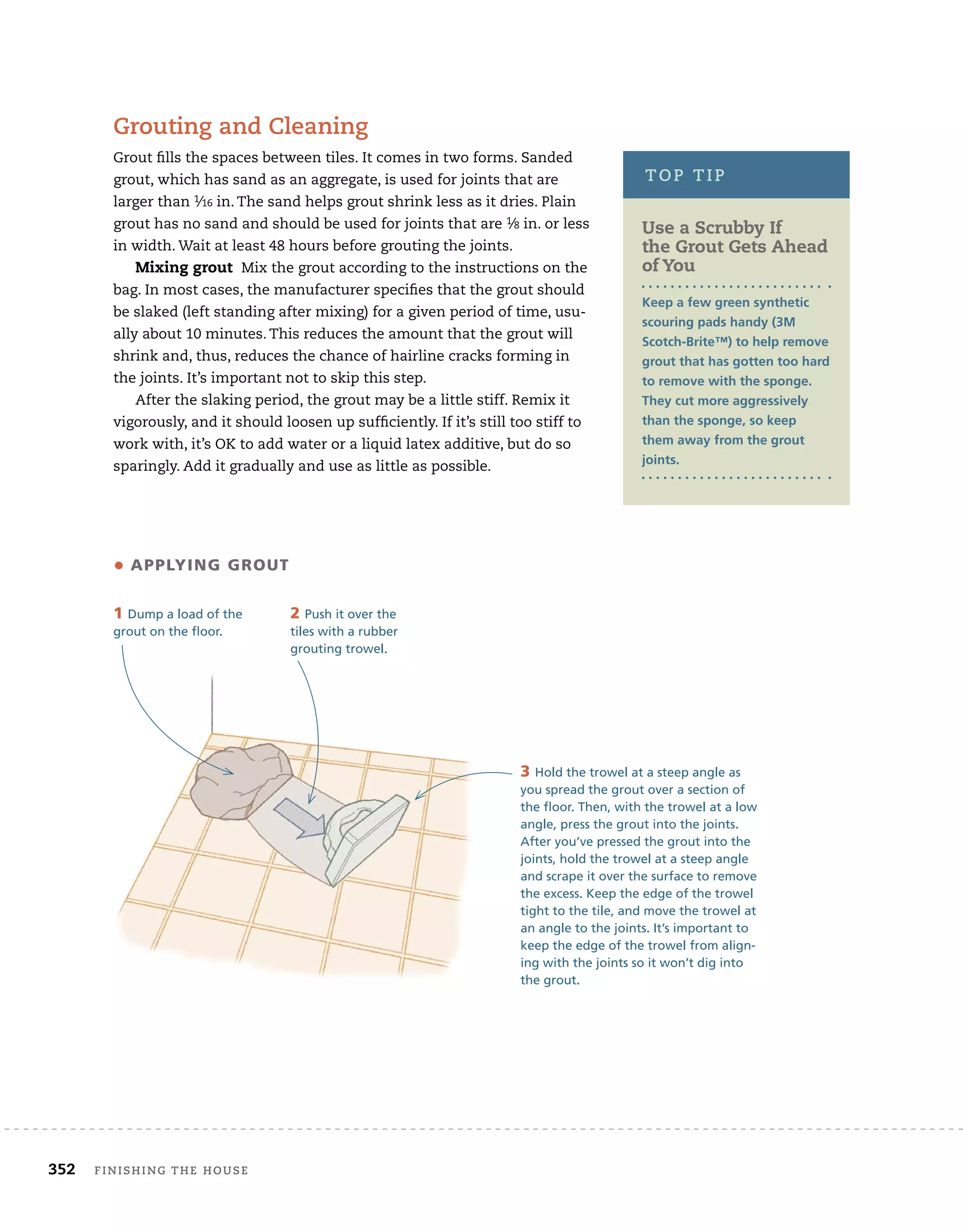

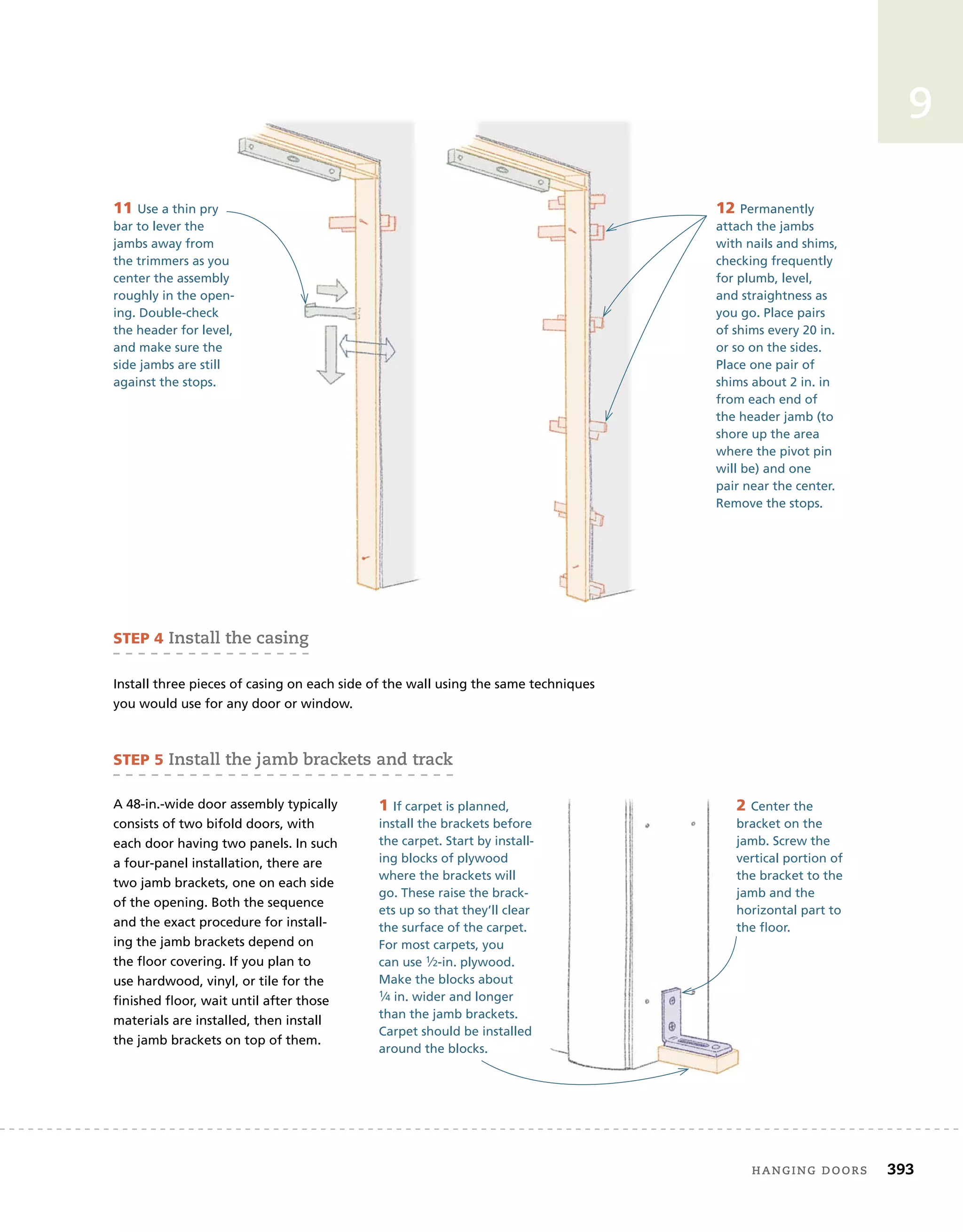

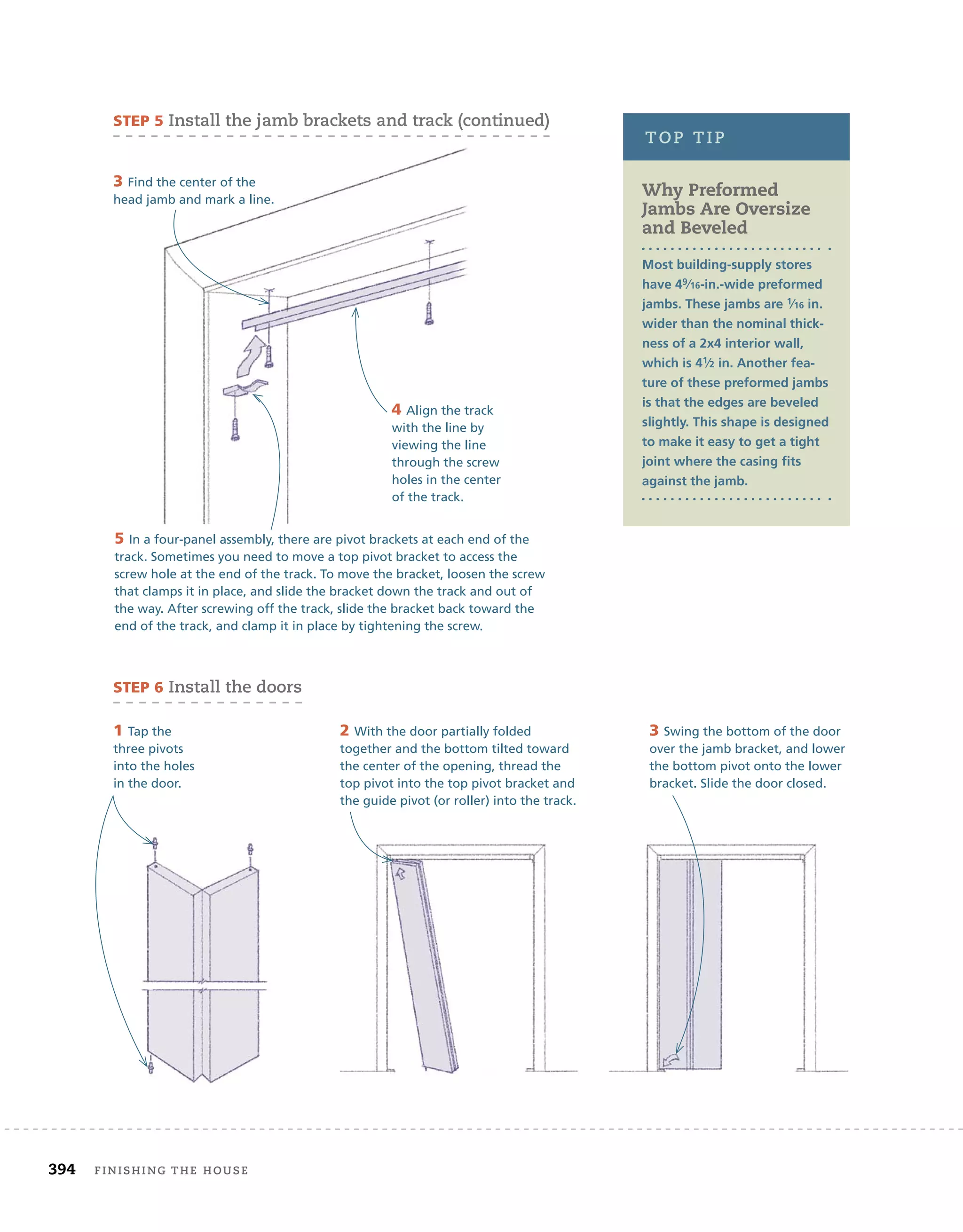

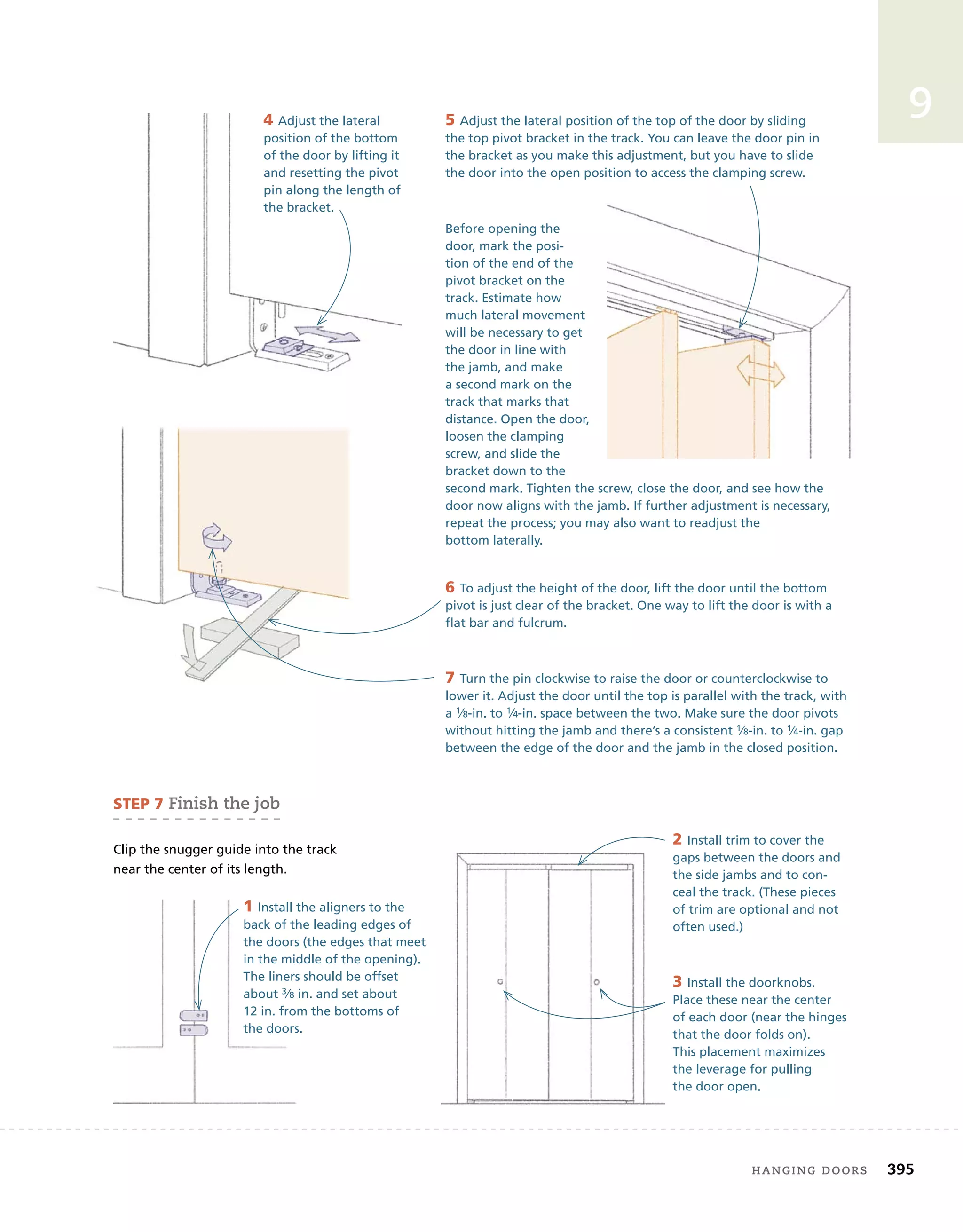

![installing trim and cabinets 401

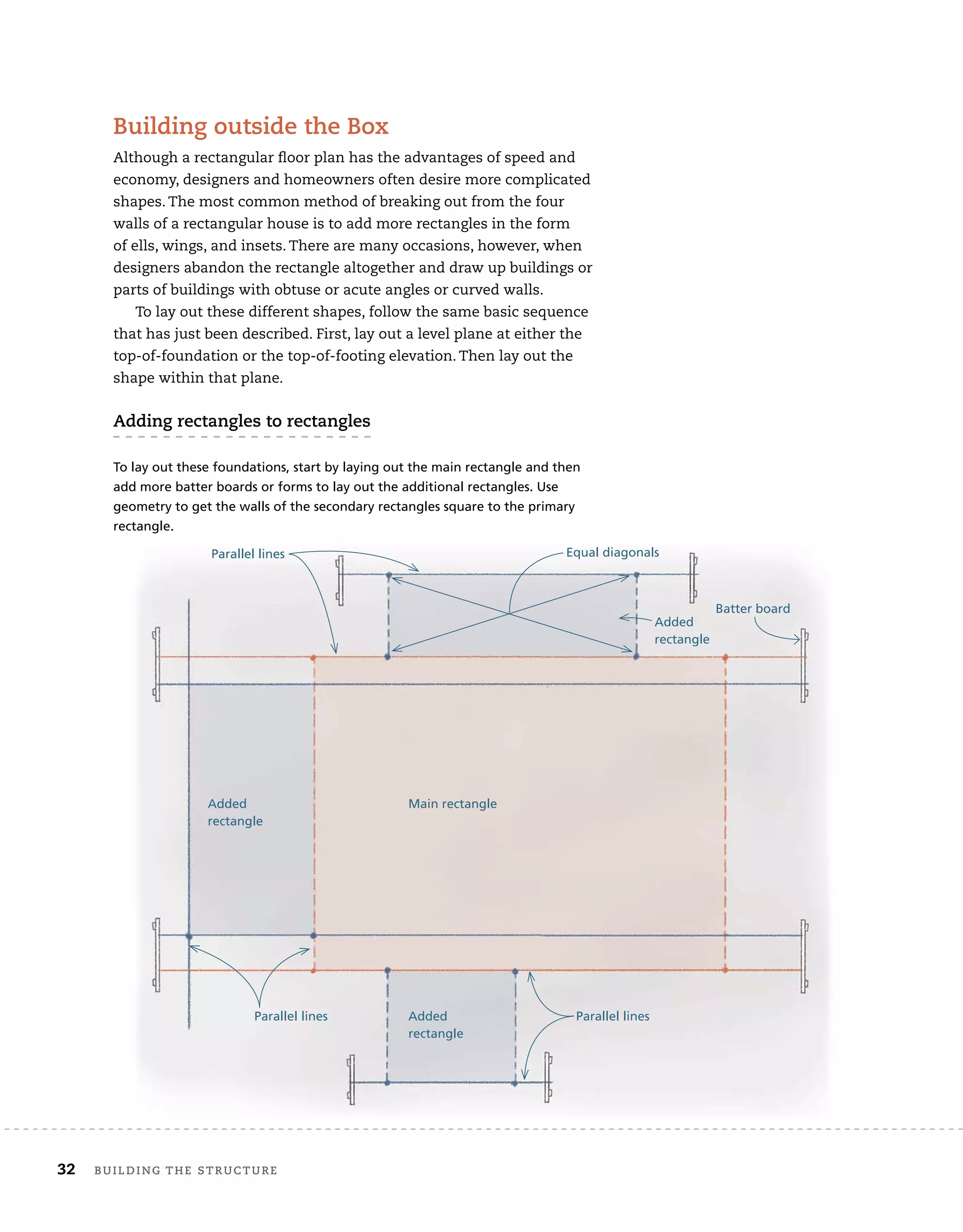

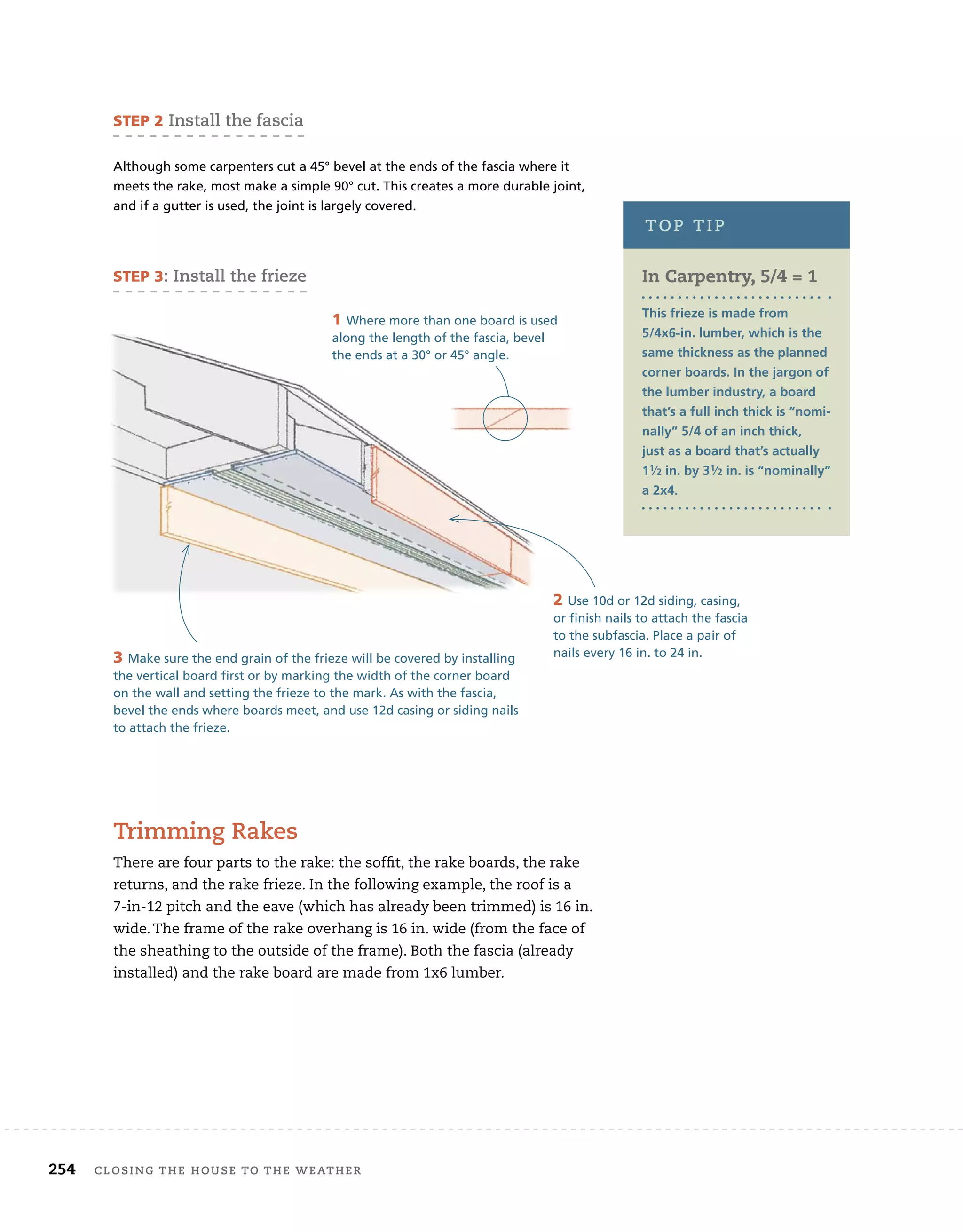

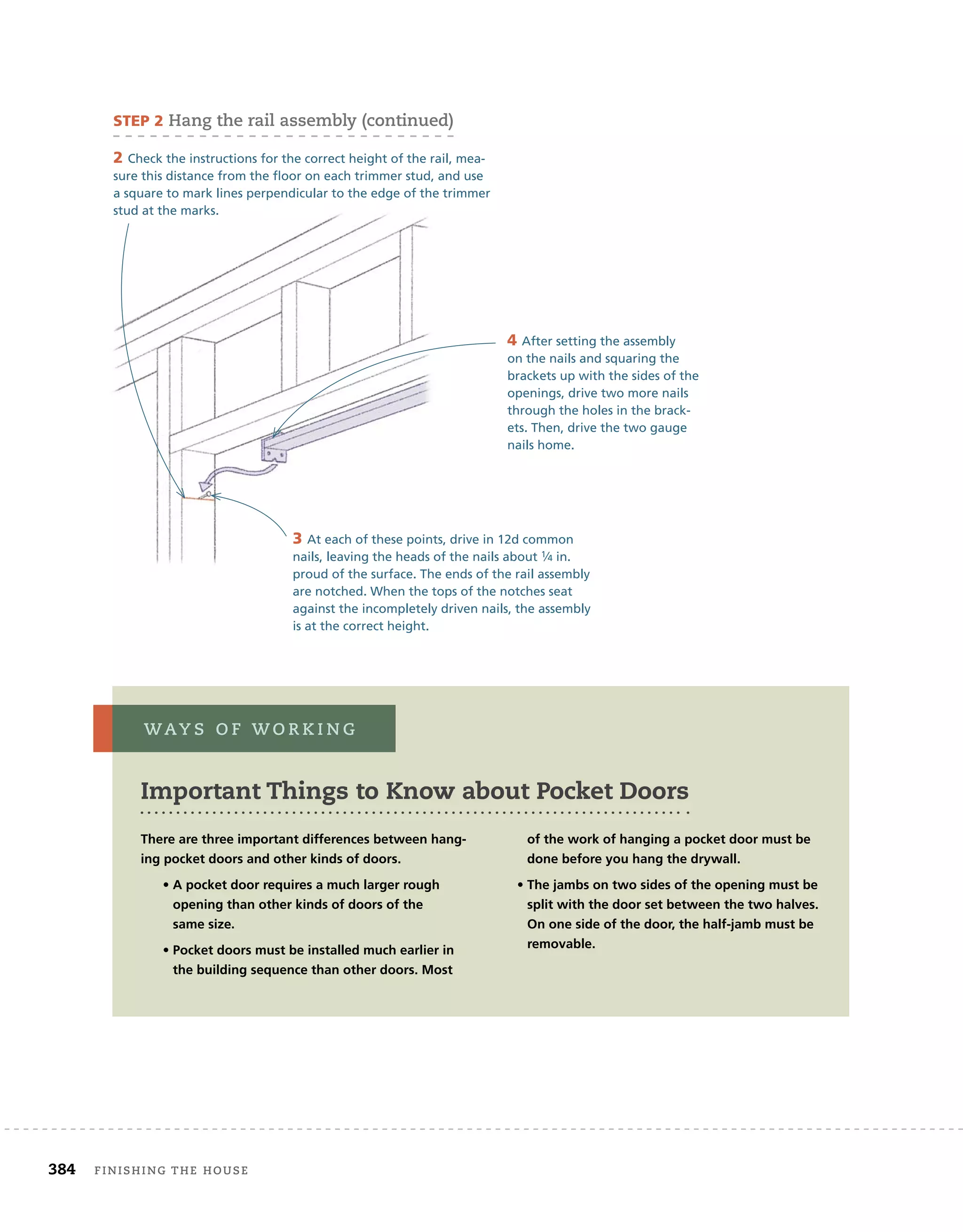

10

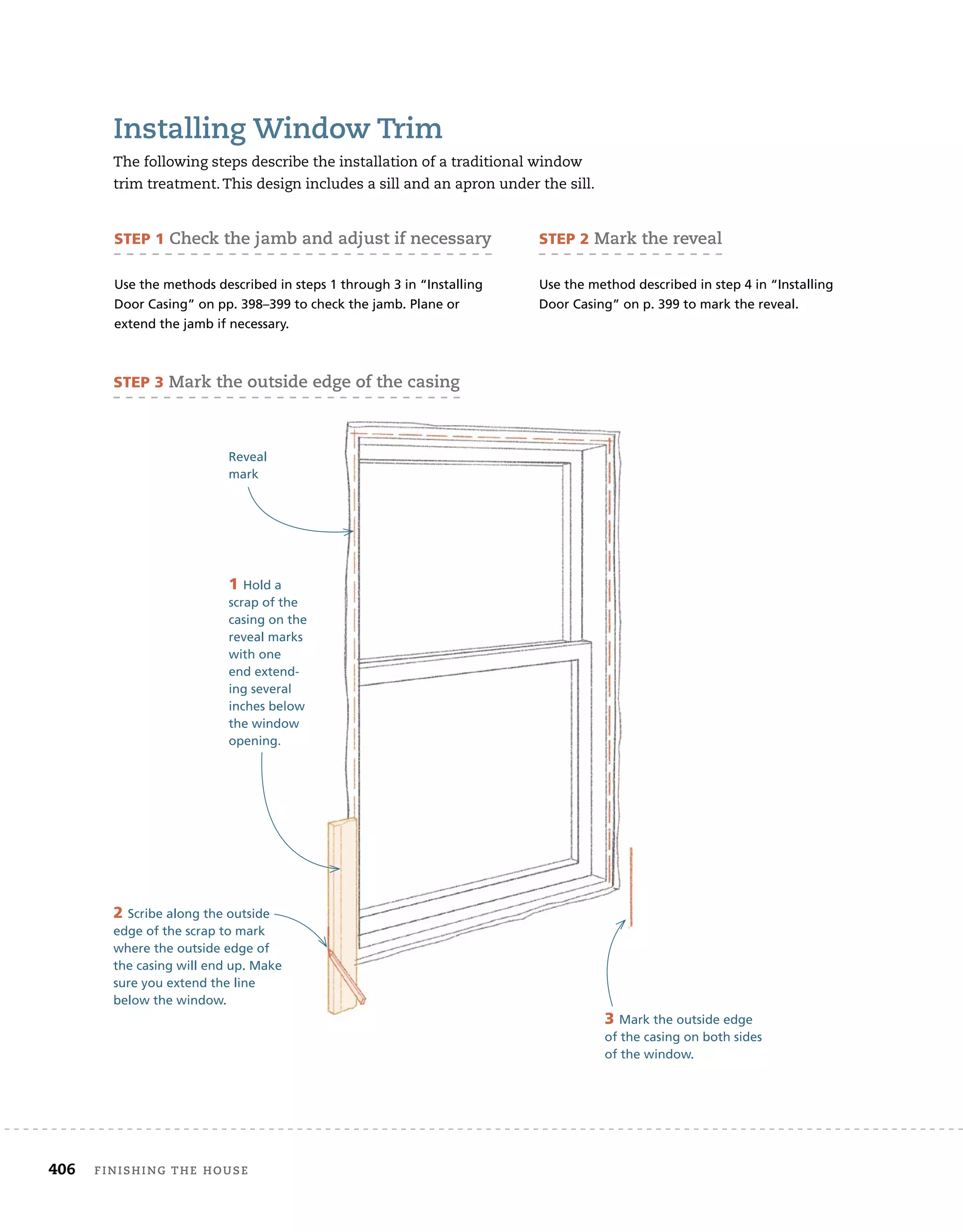

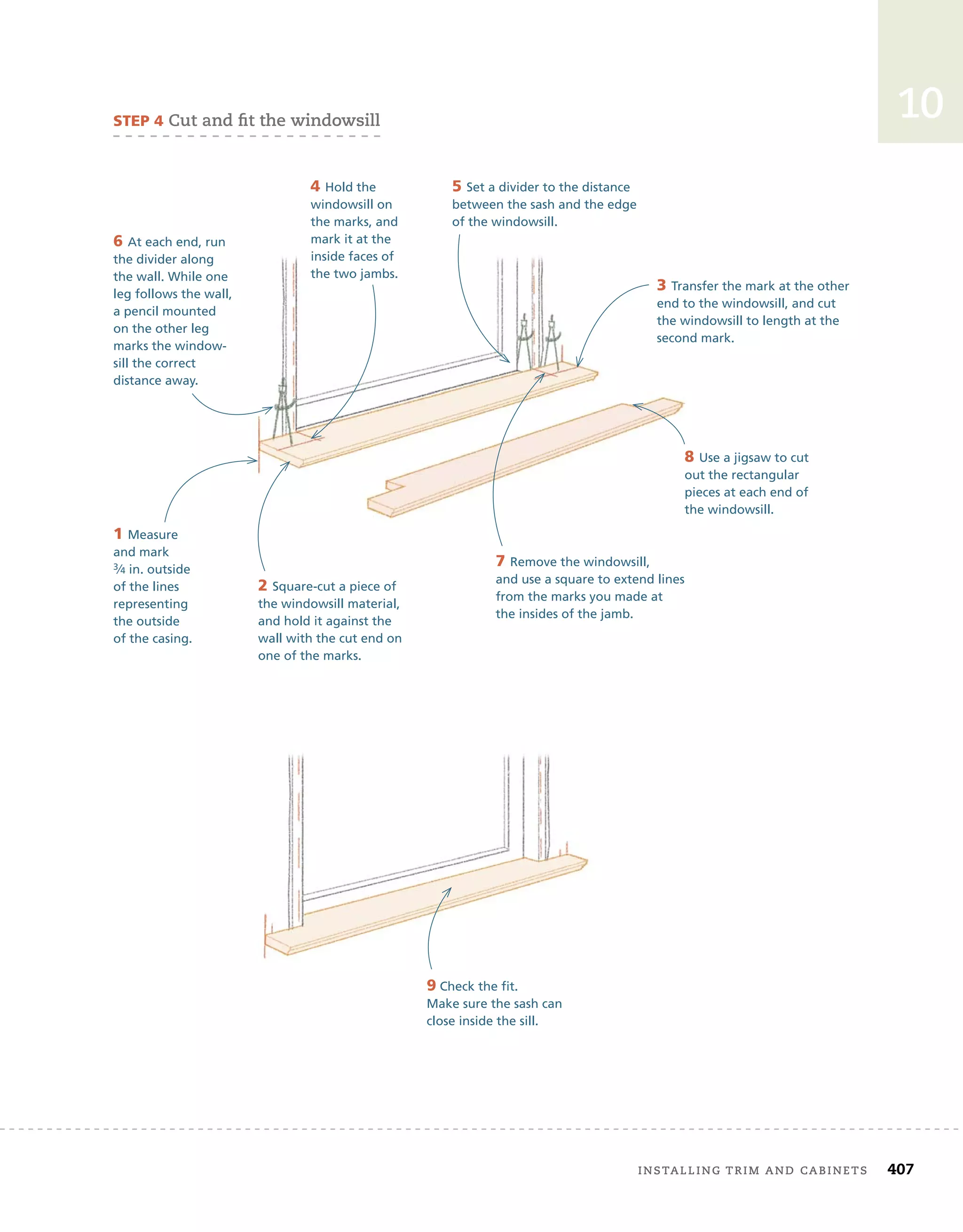

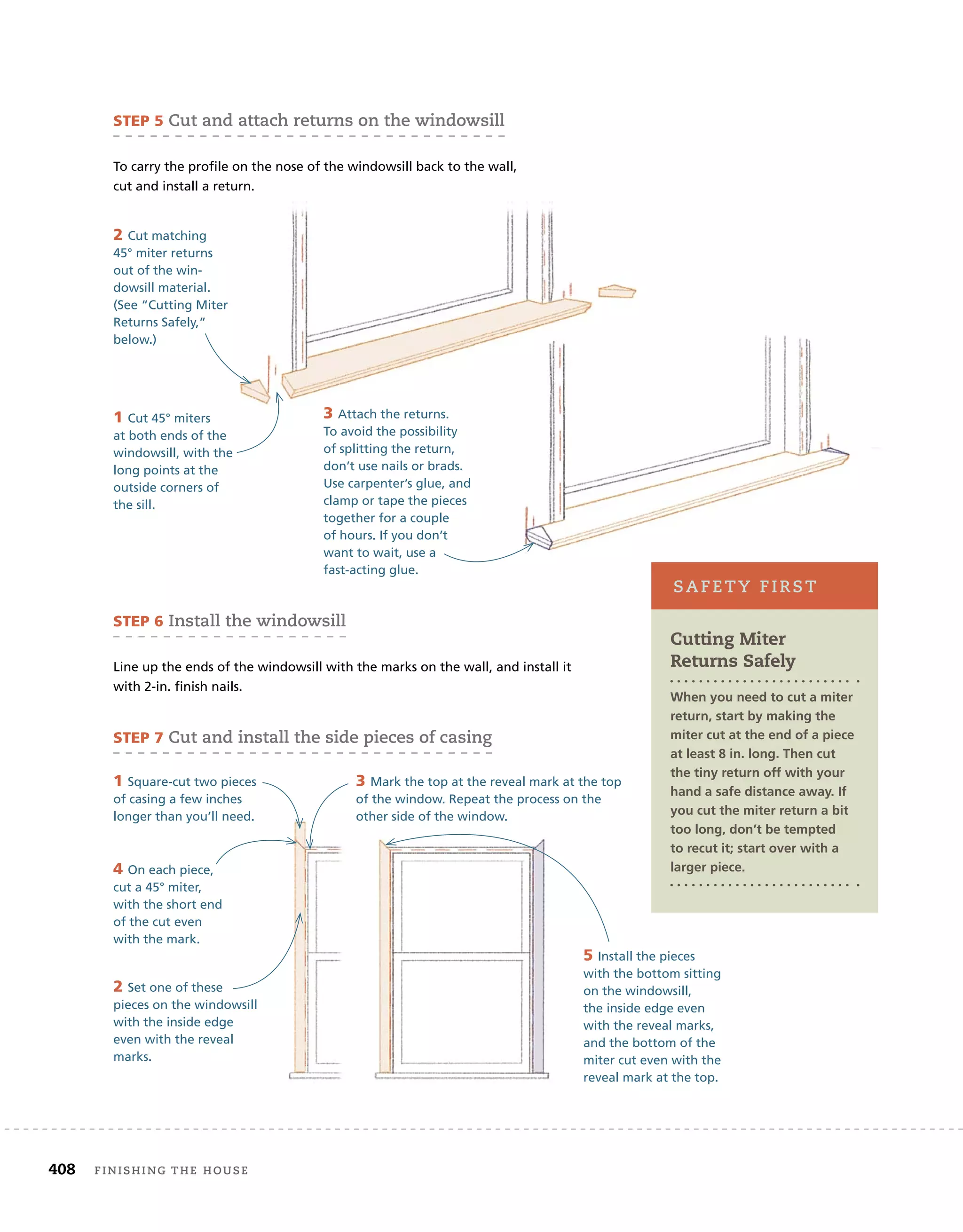

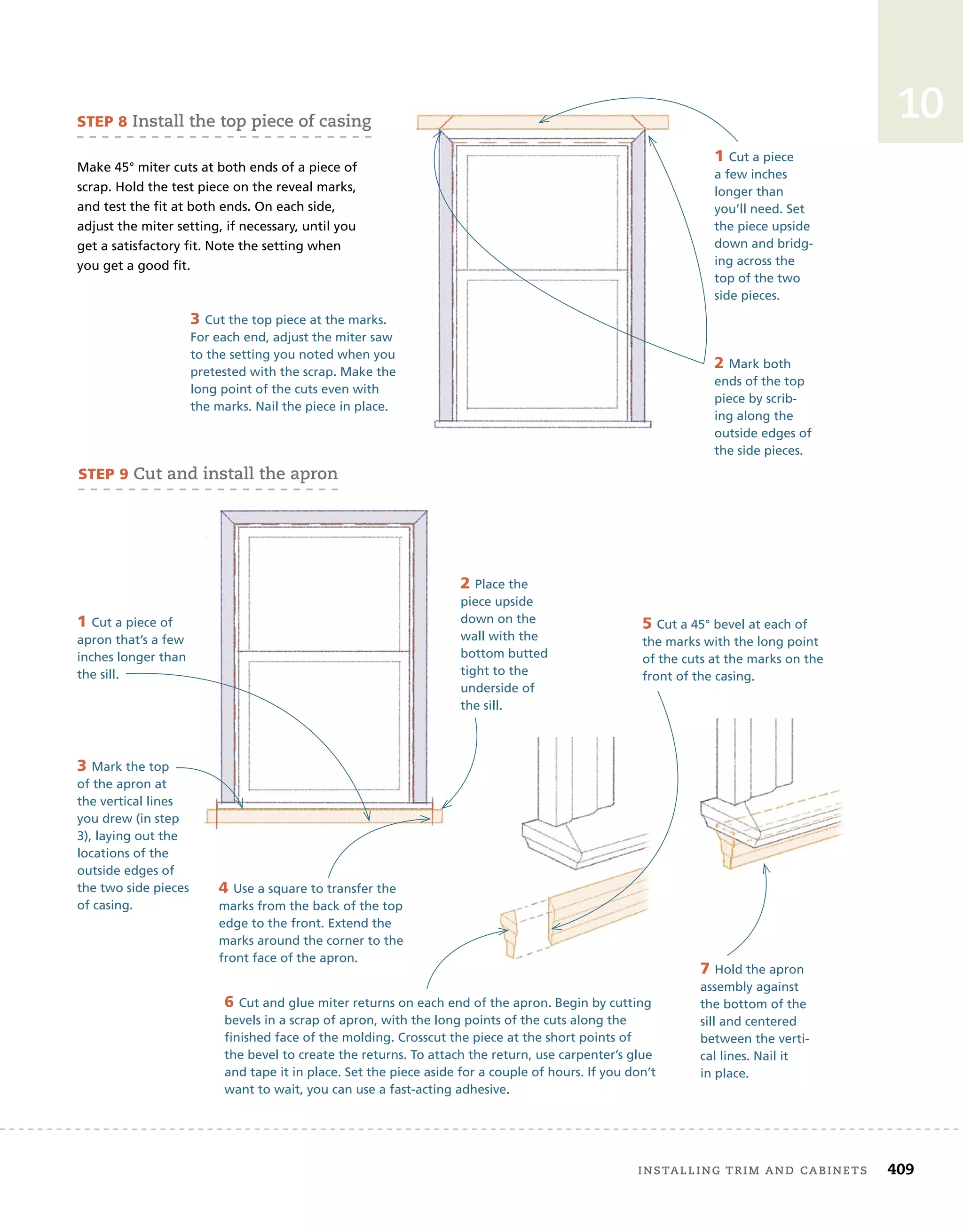

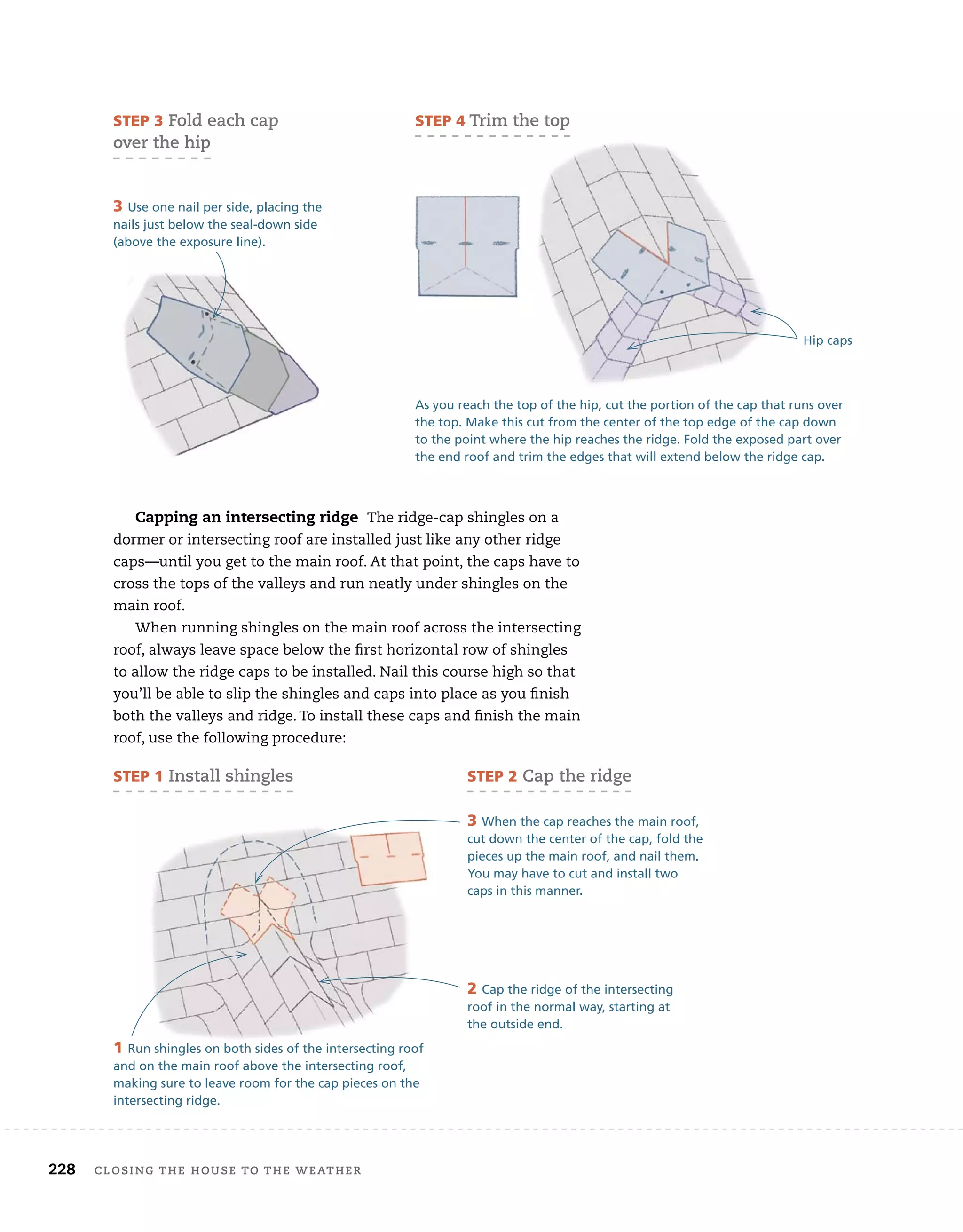

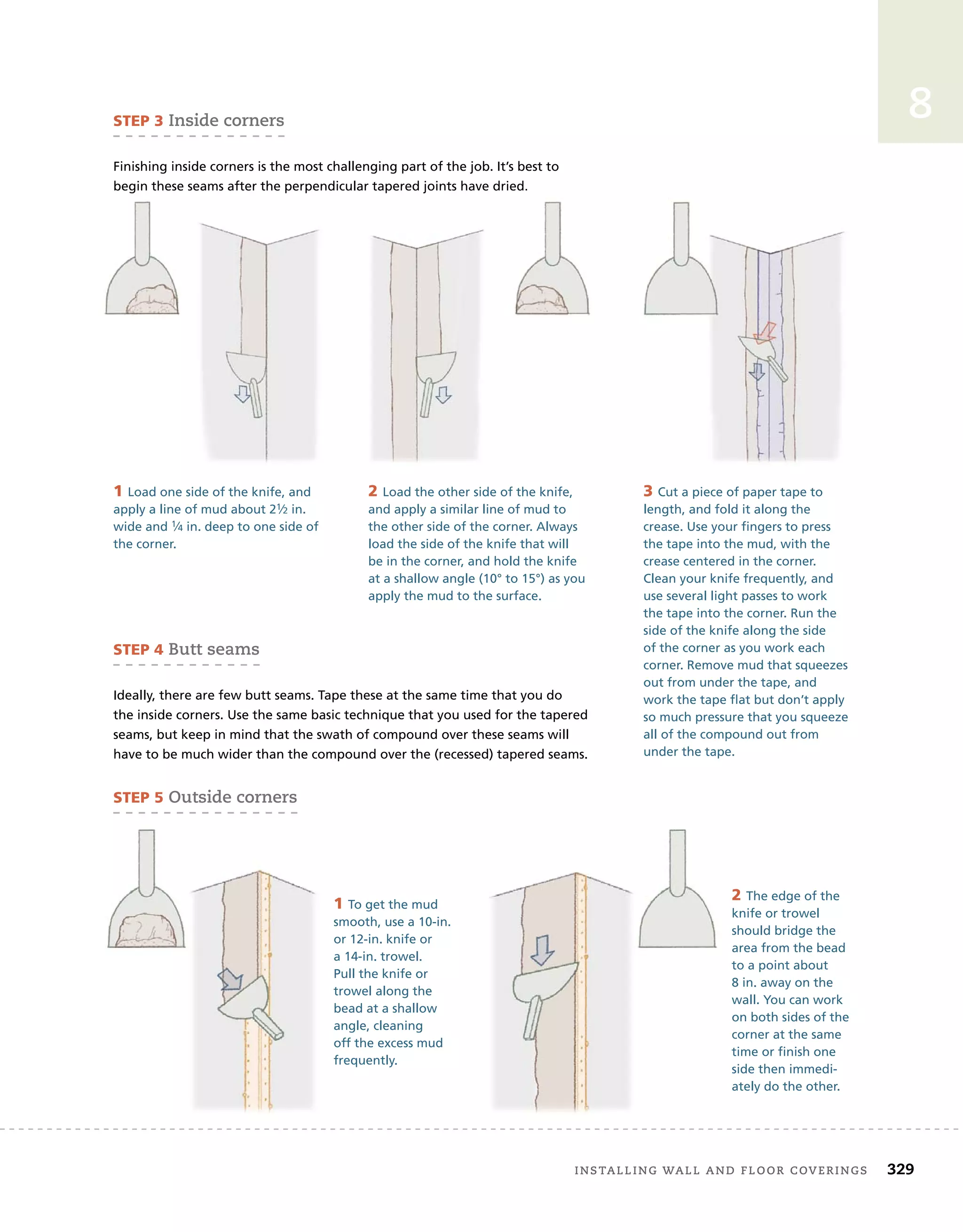

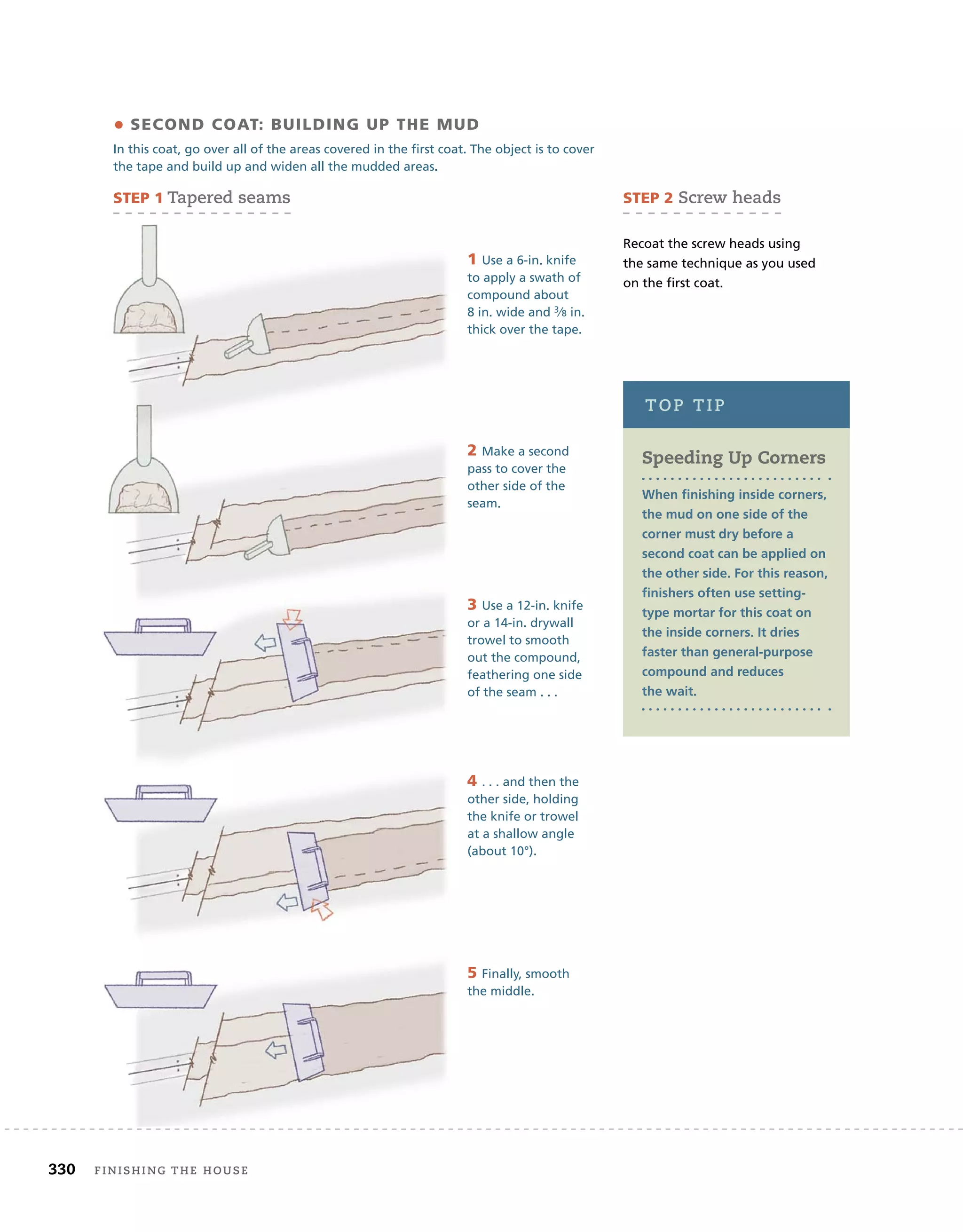

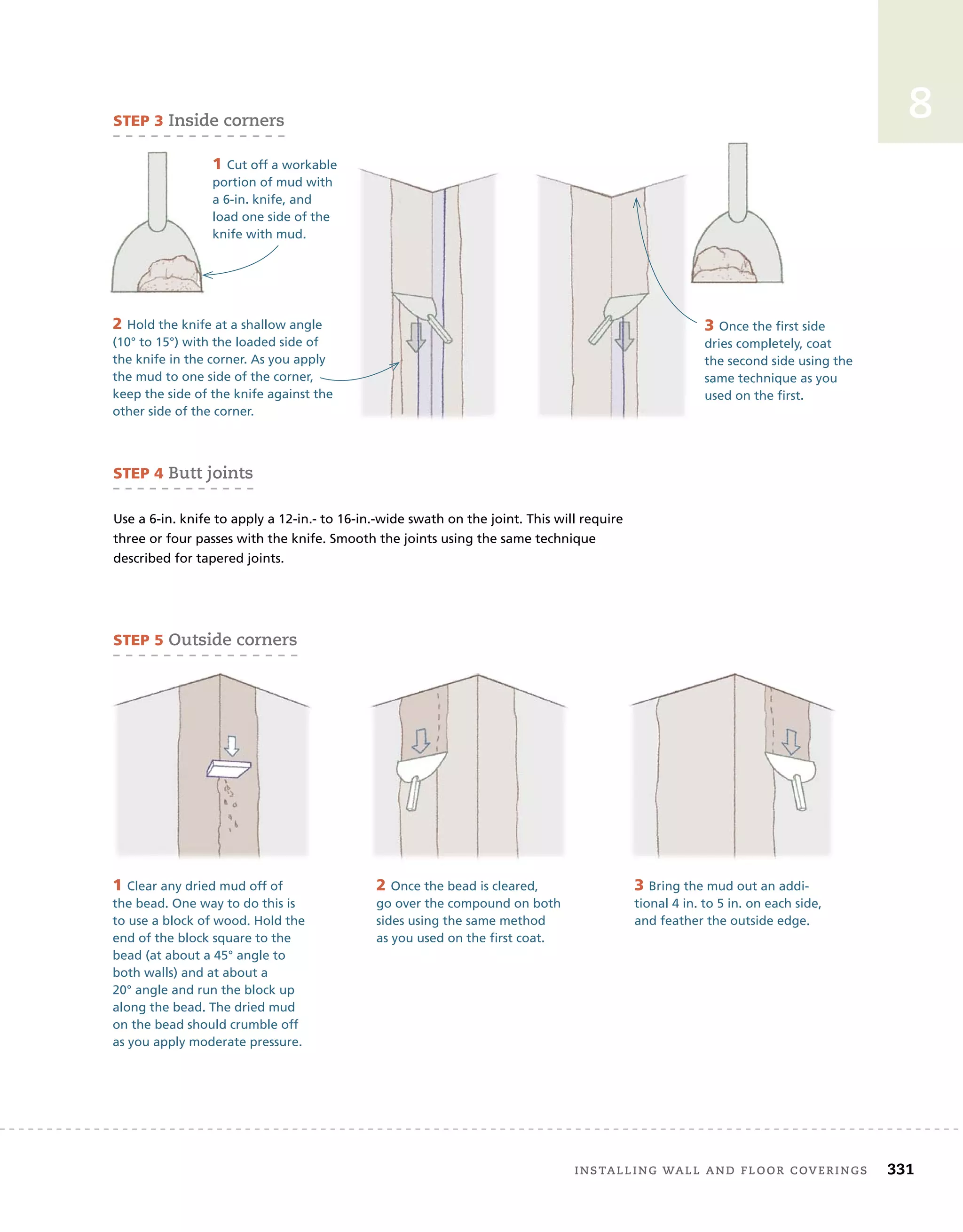

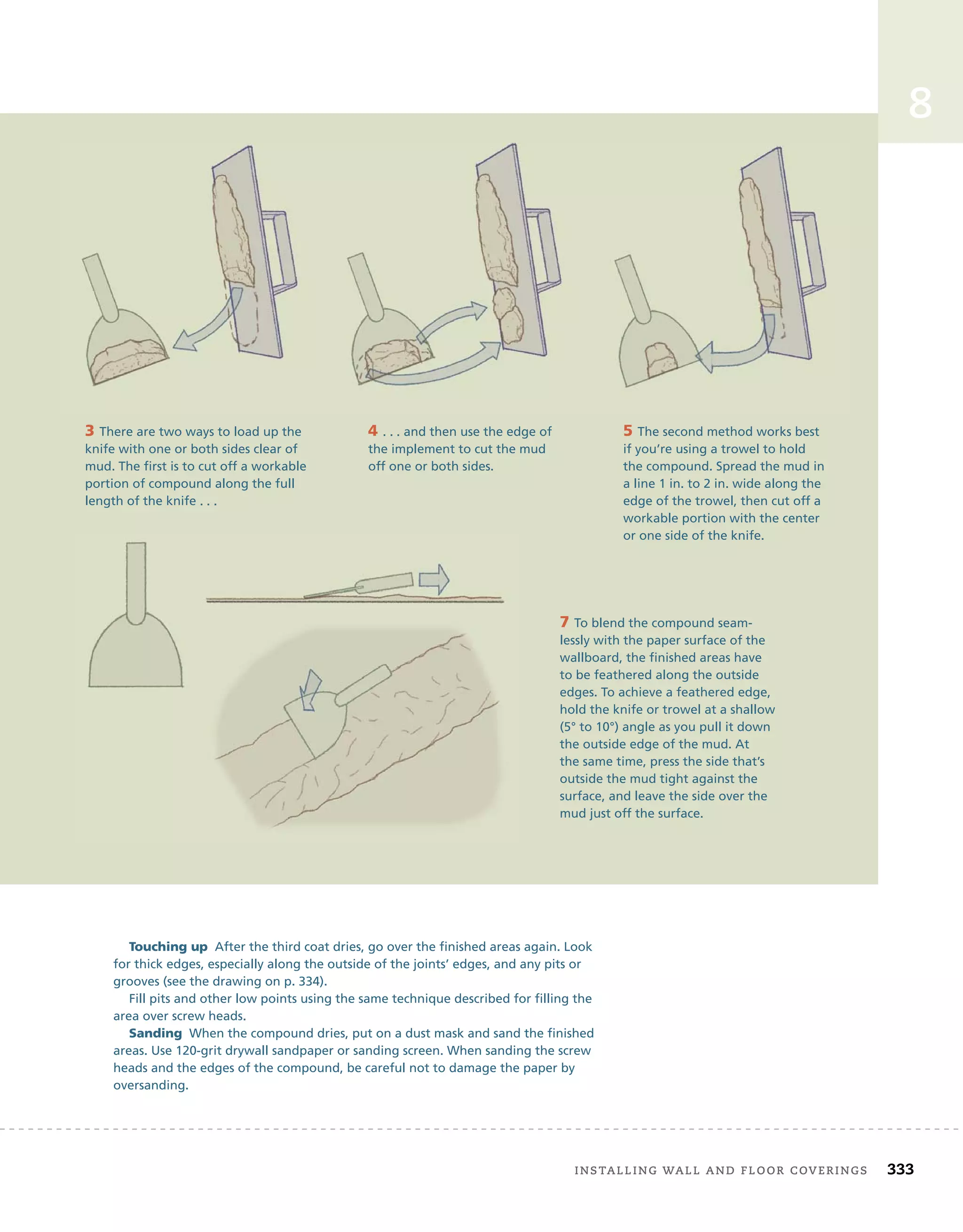

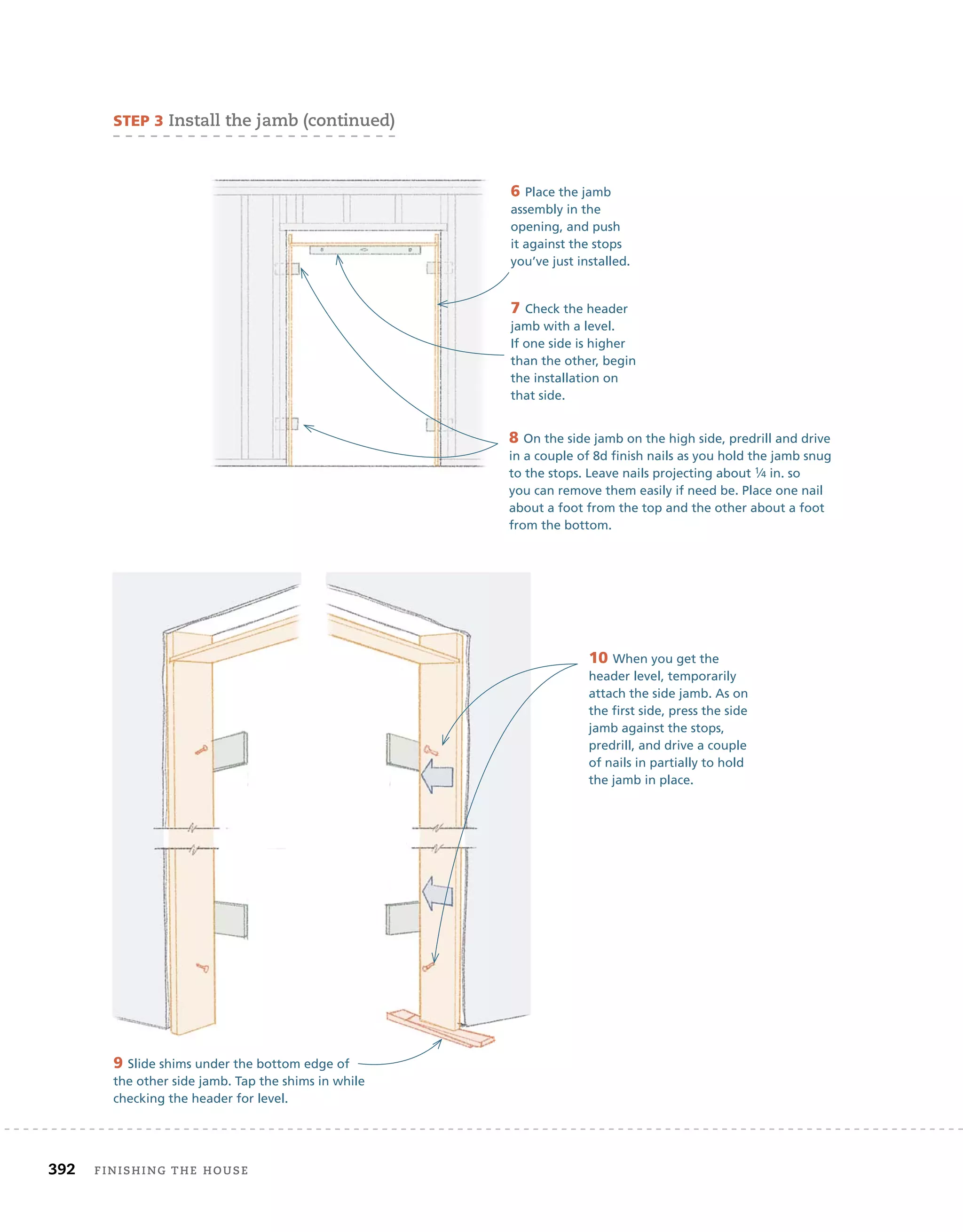

installing Window trim

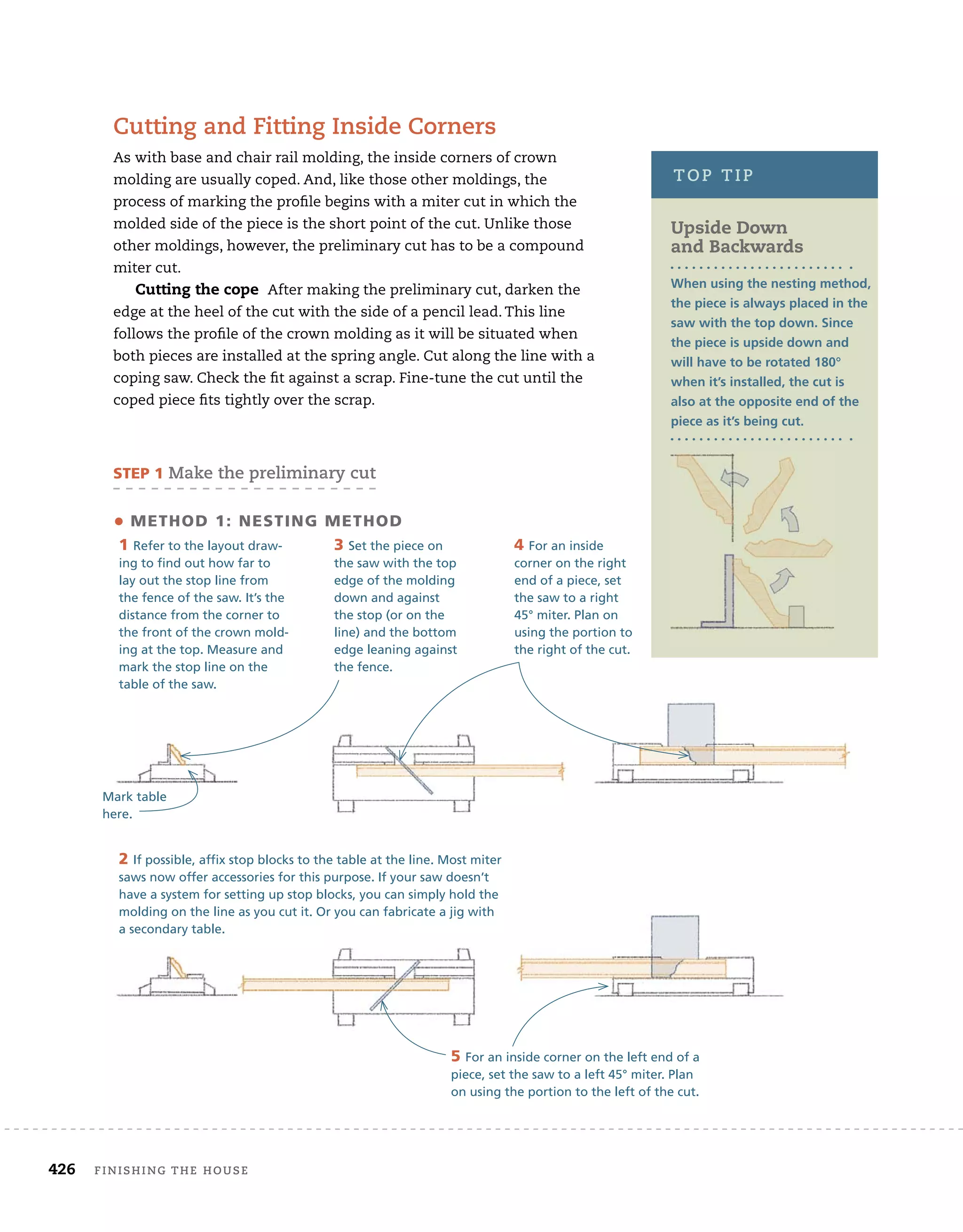

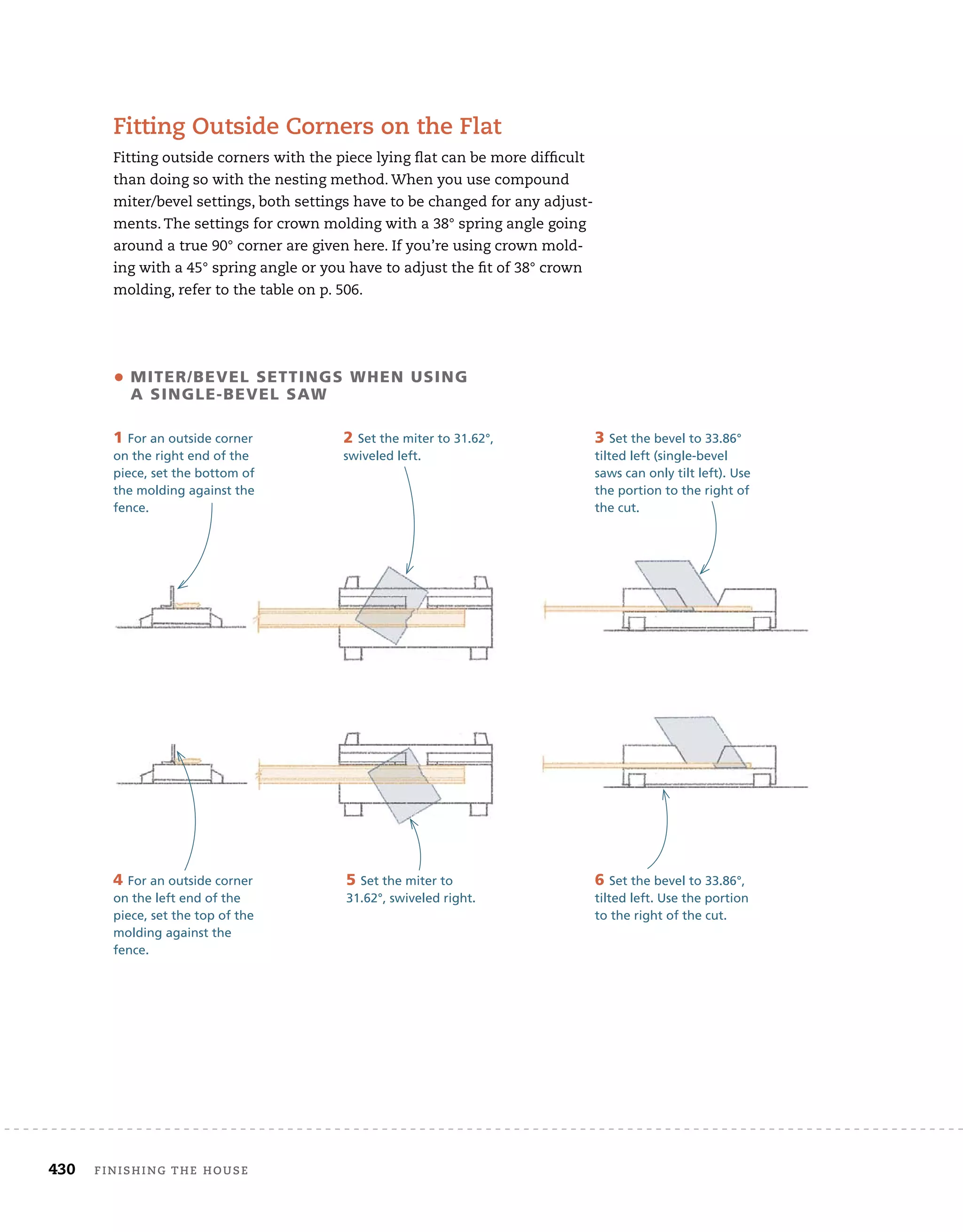

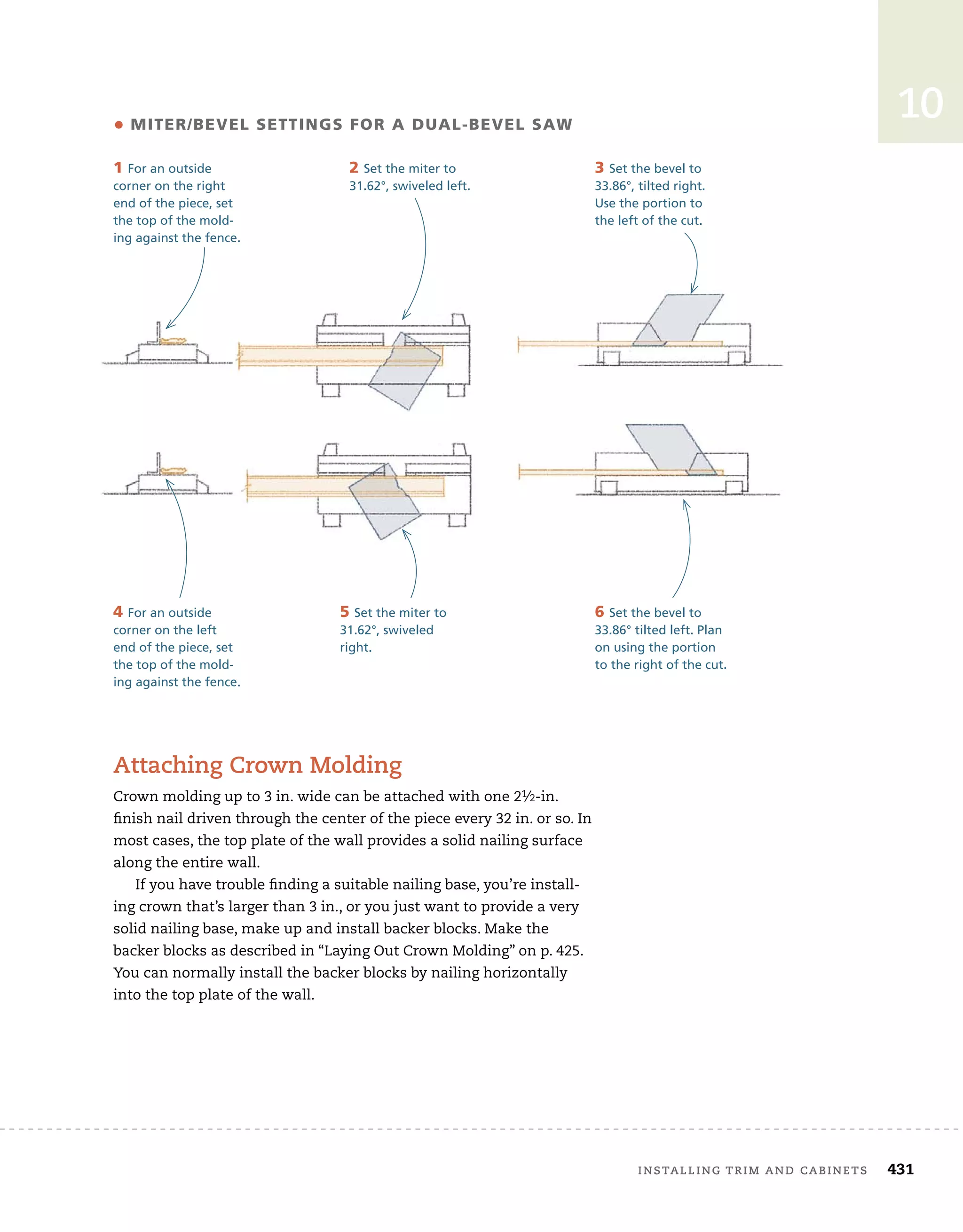

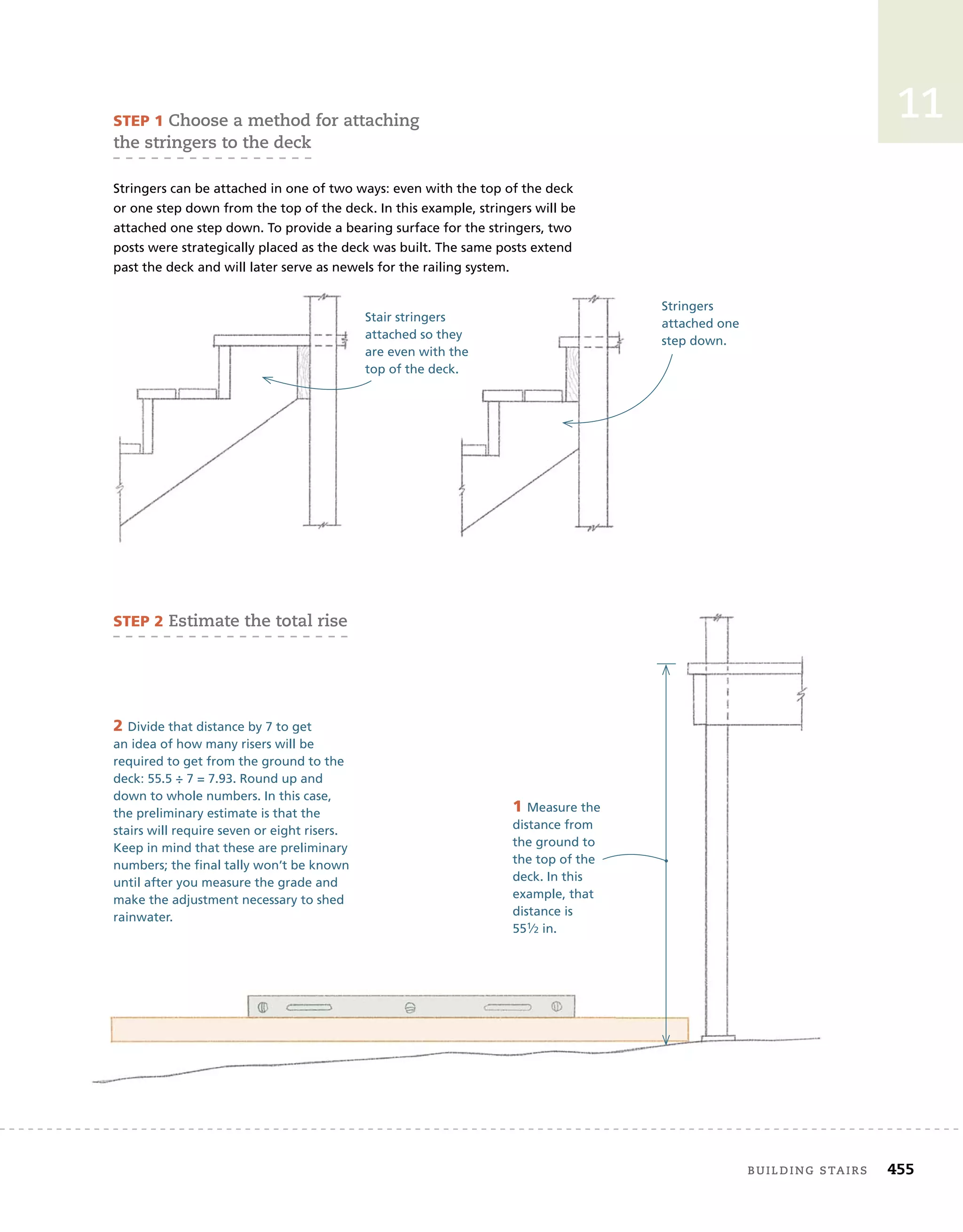

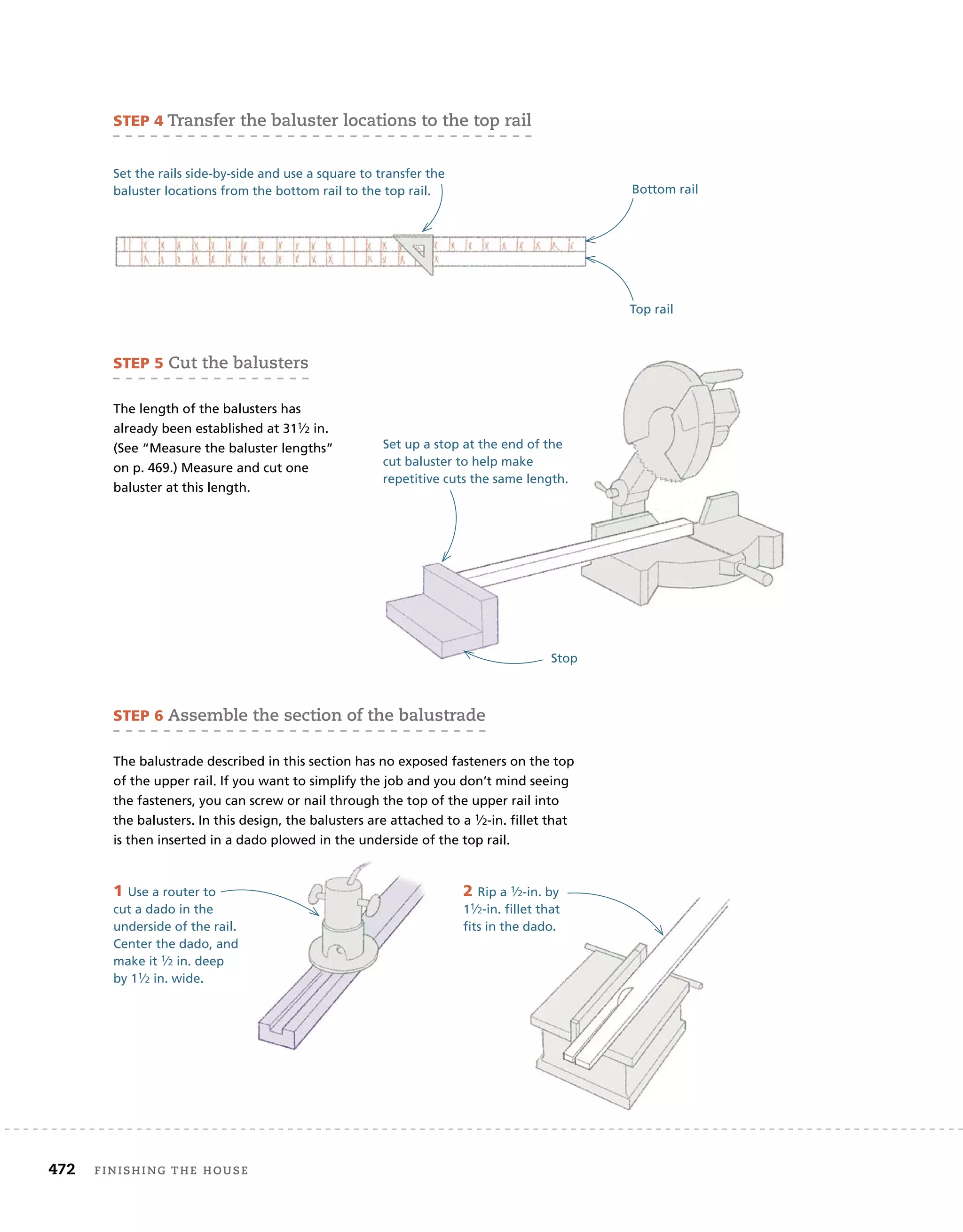

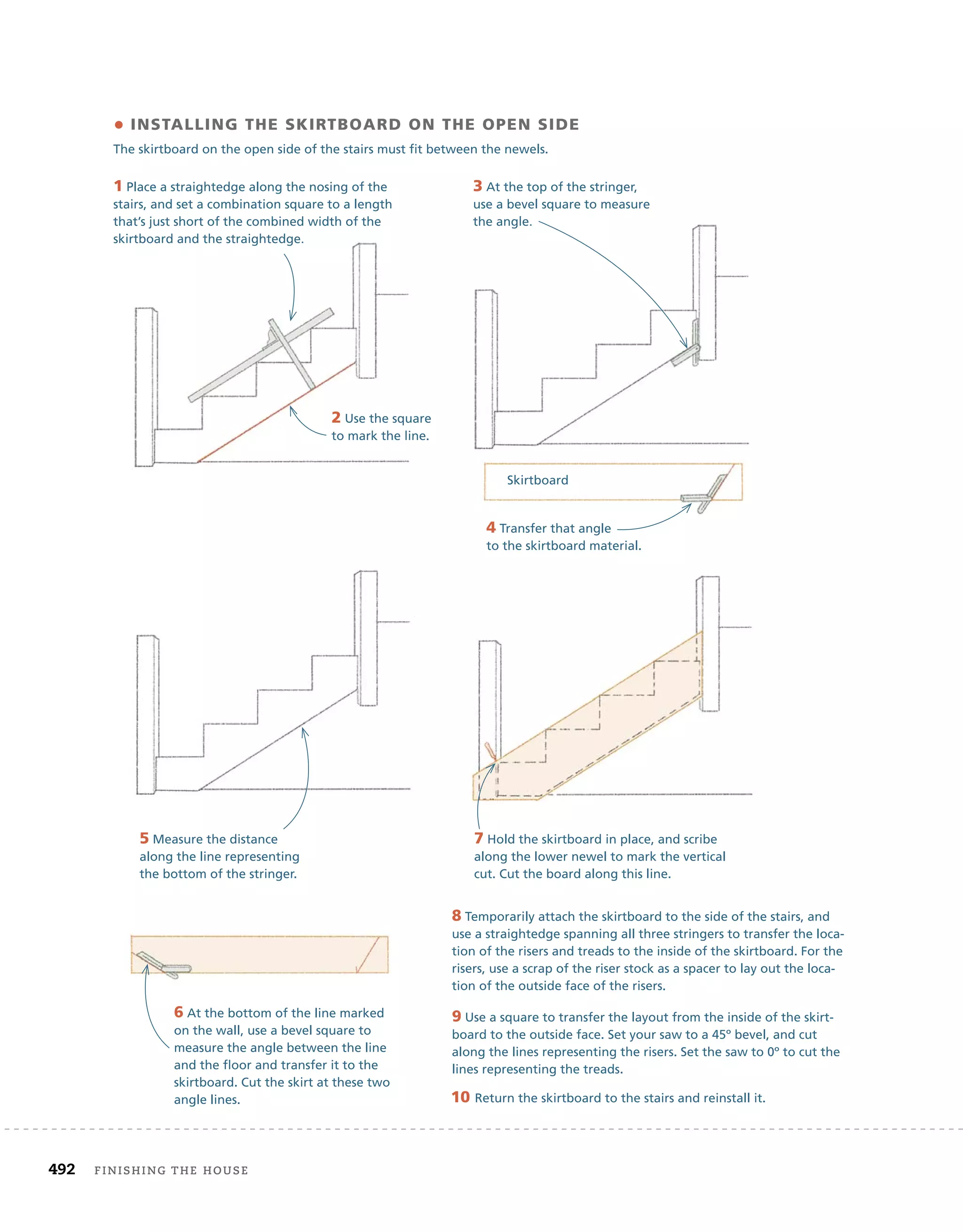

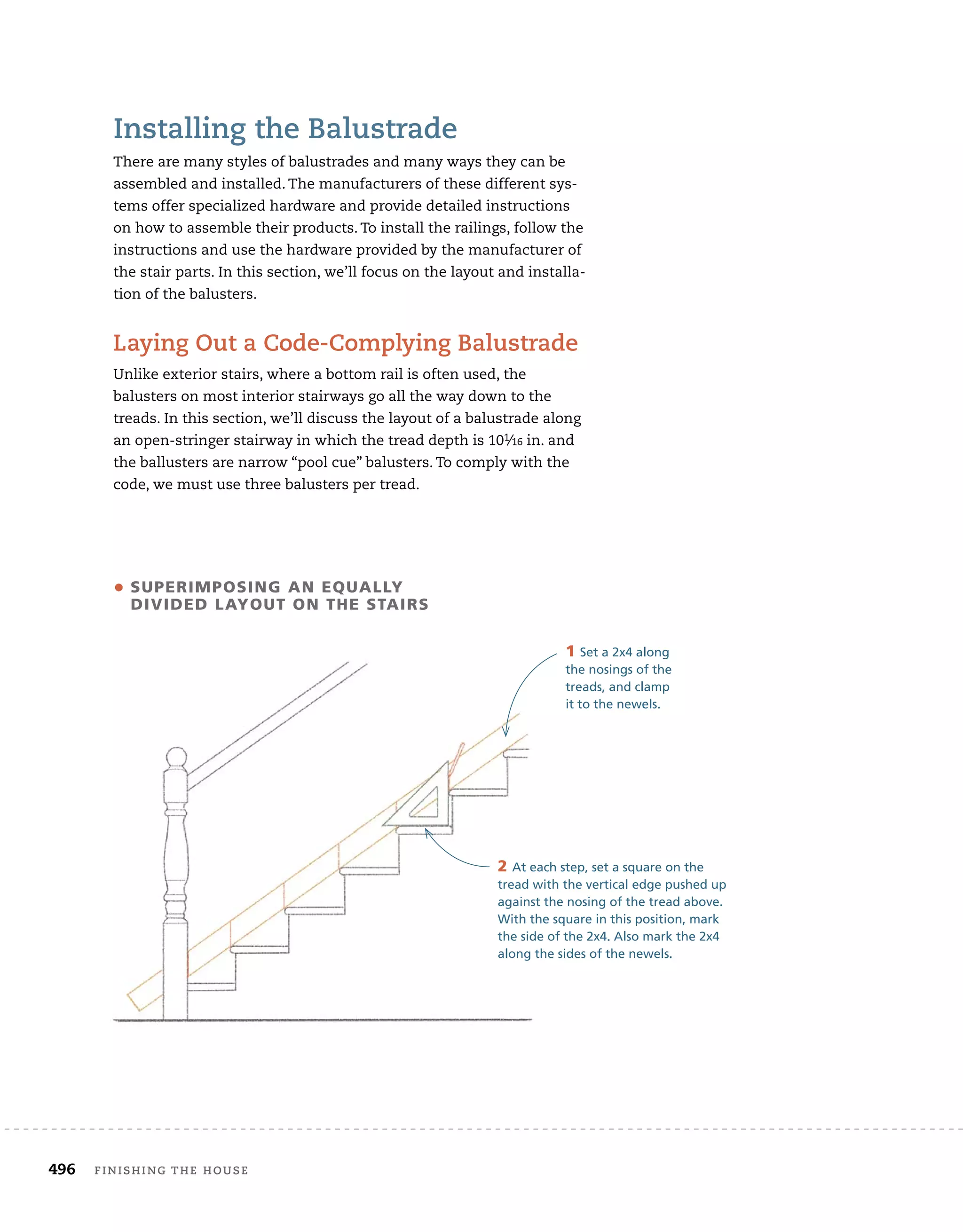

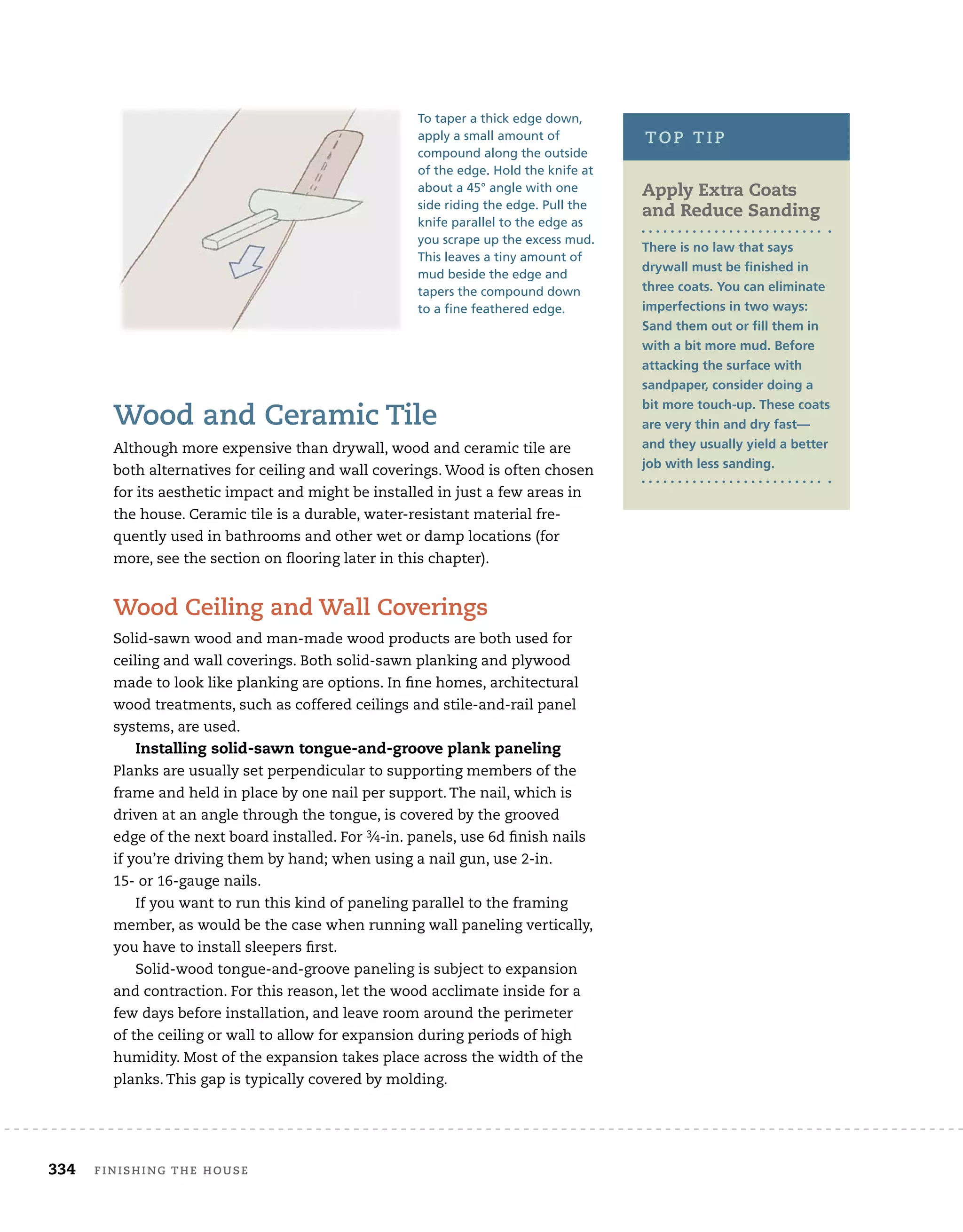

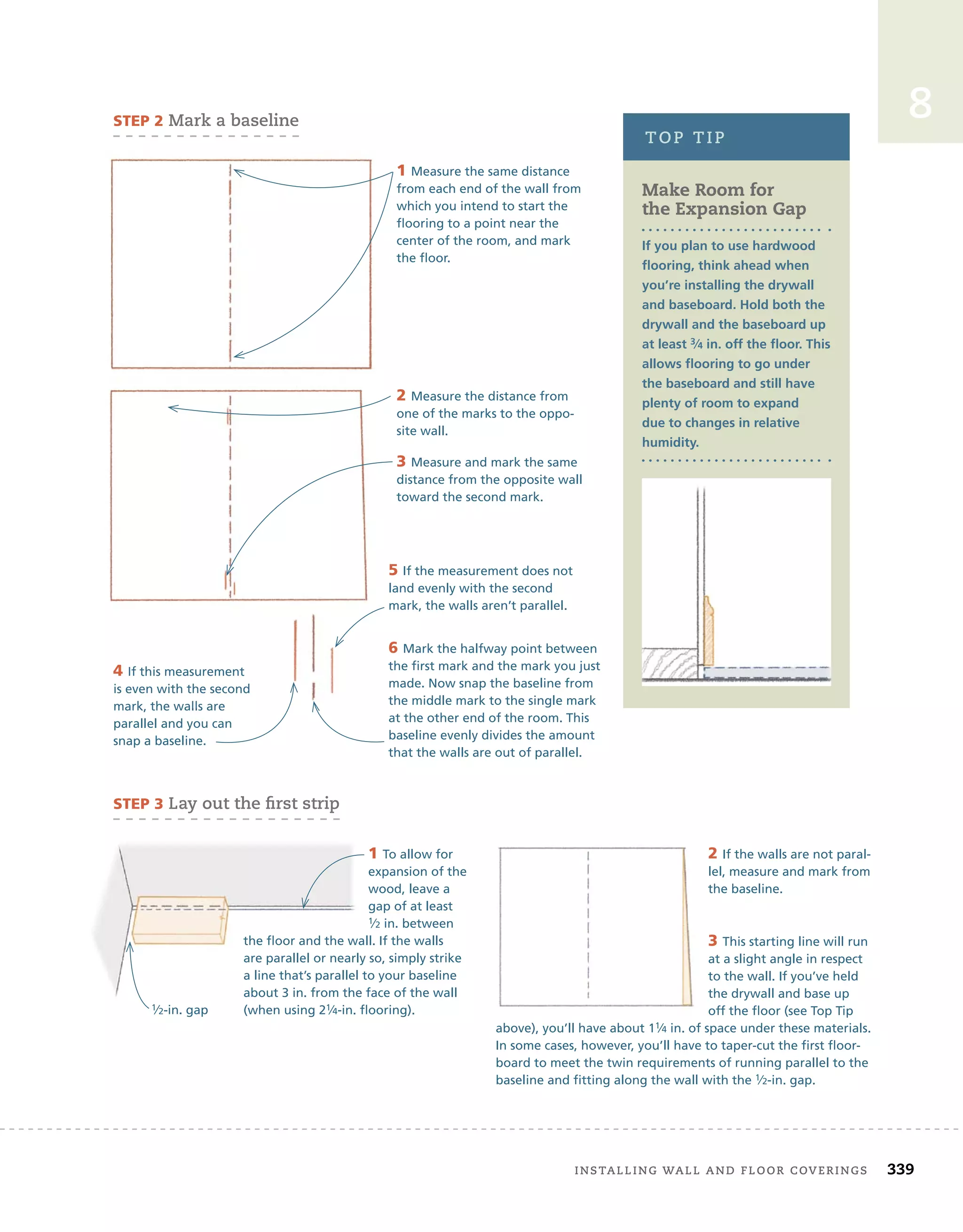

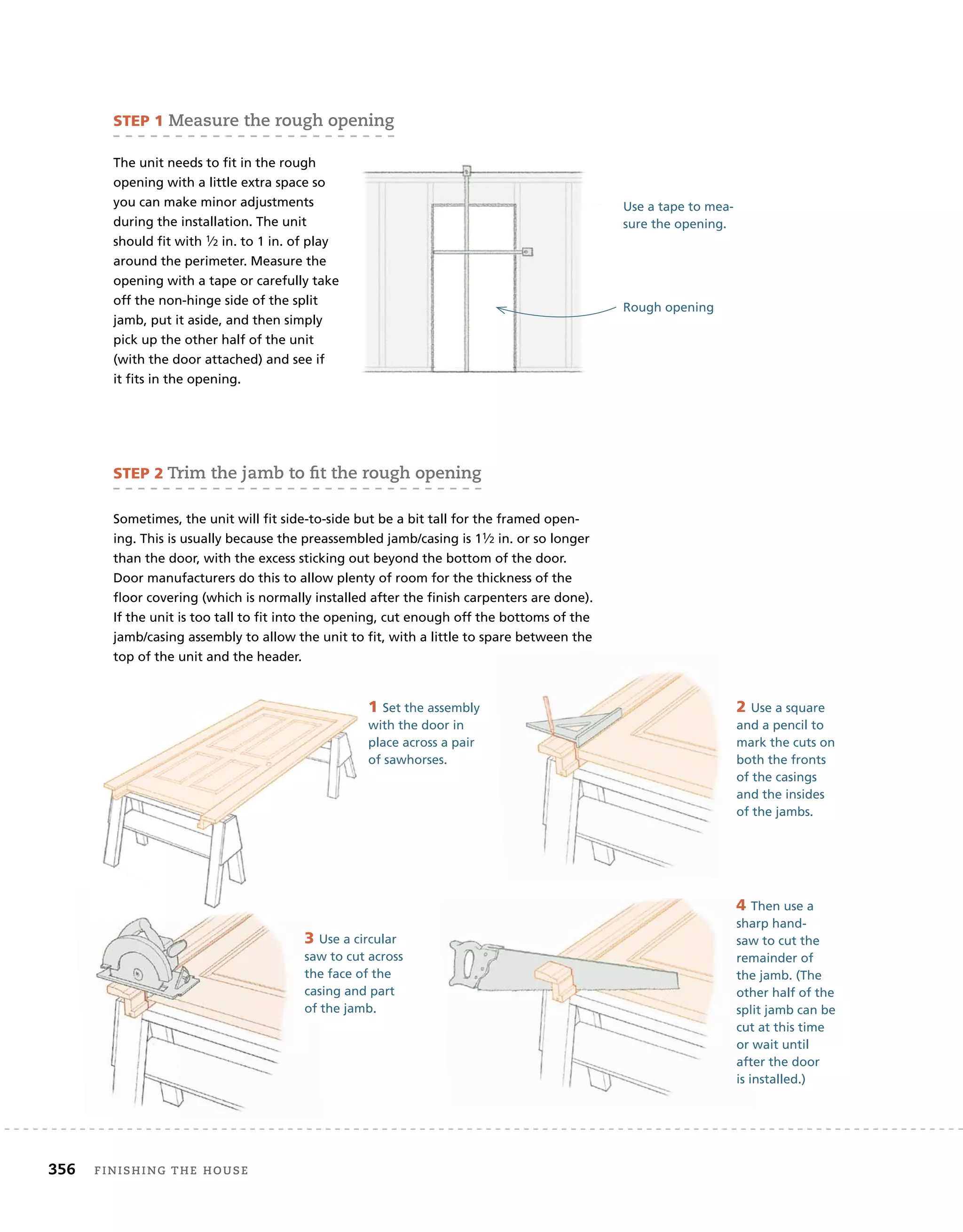

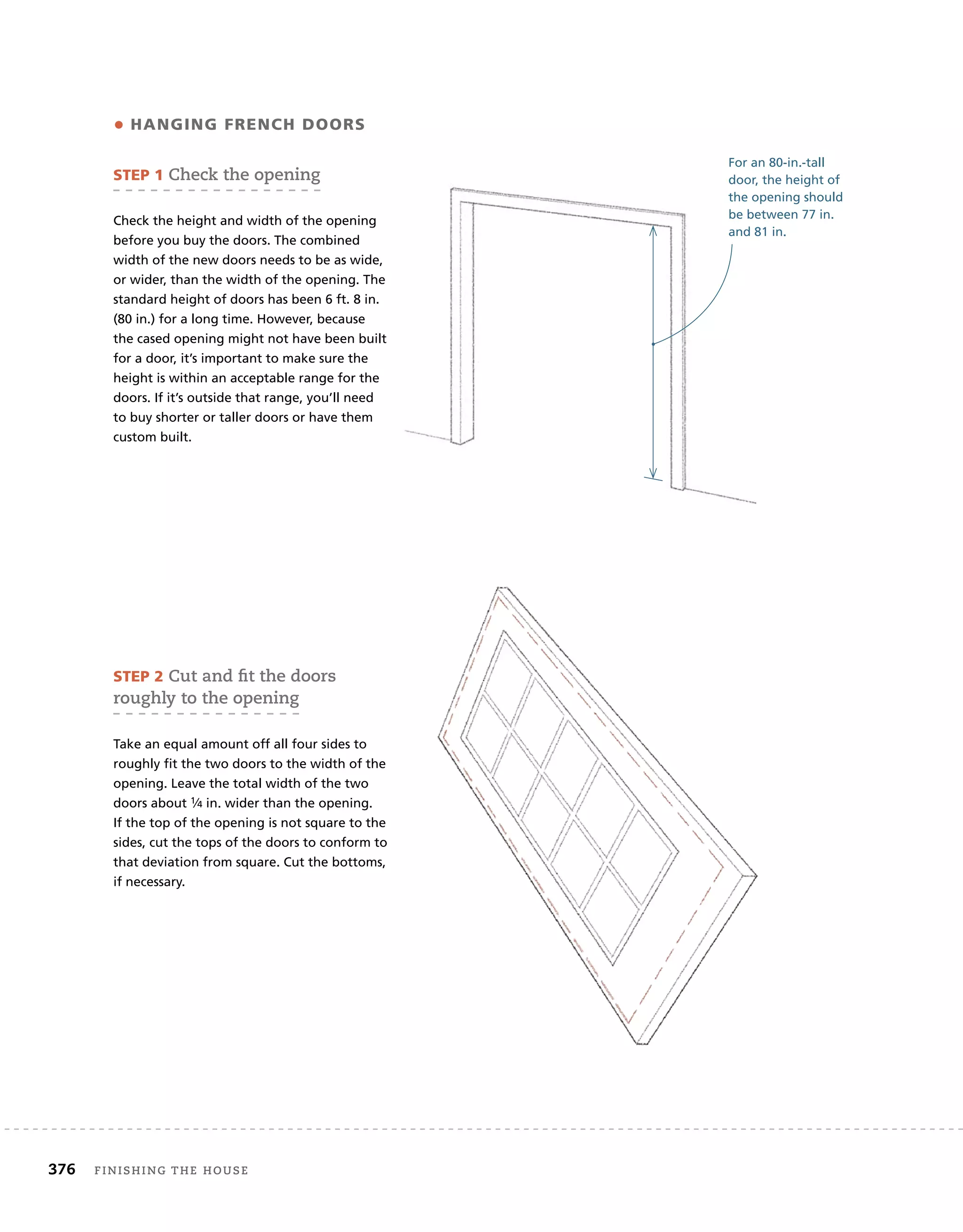

The following steps describe the installation of a traditional window

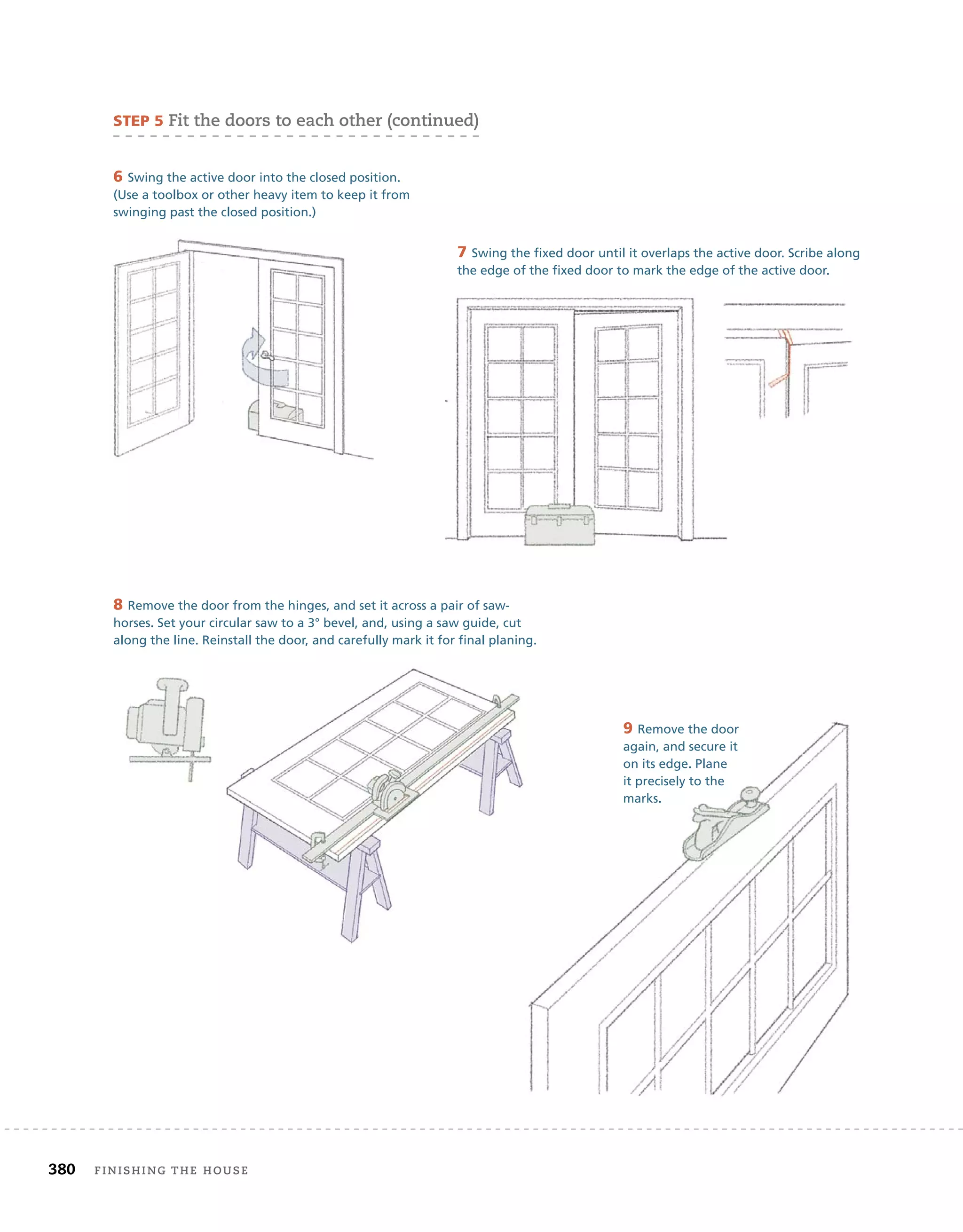

trim treatment. This design includes a sill and an apron under the

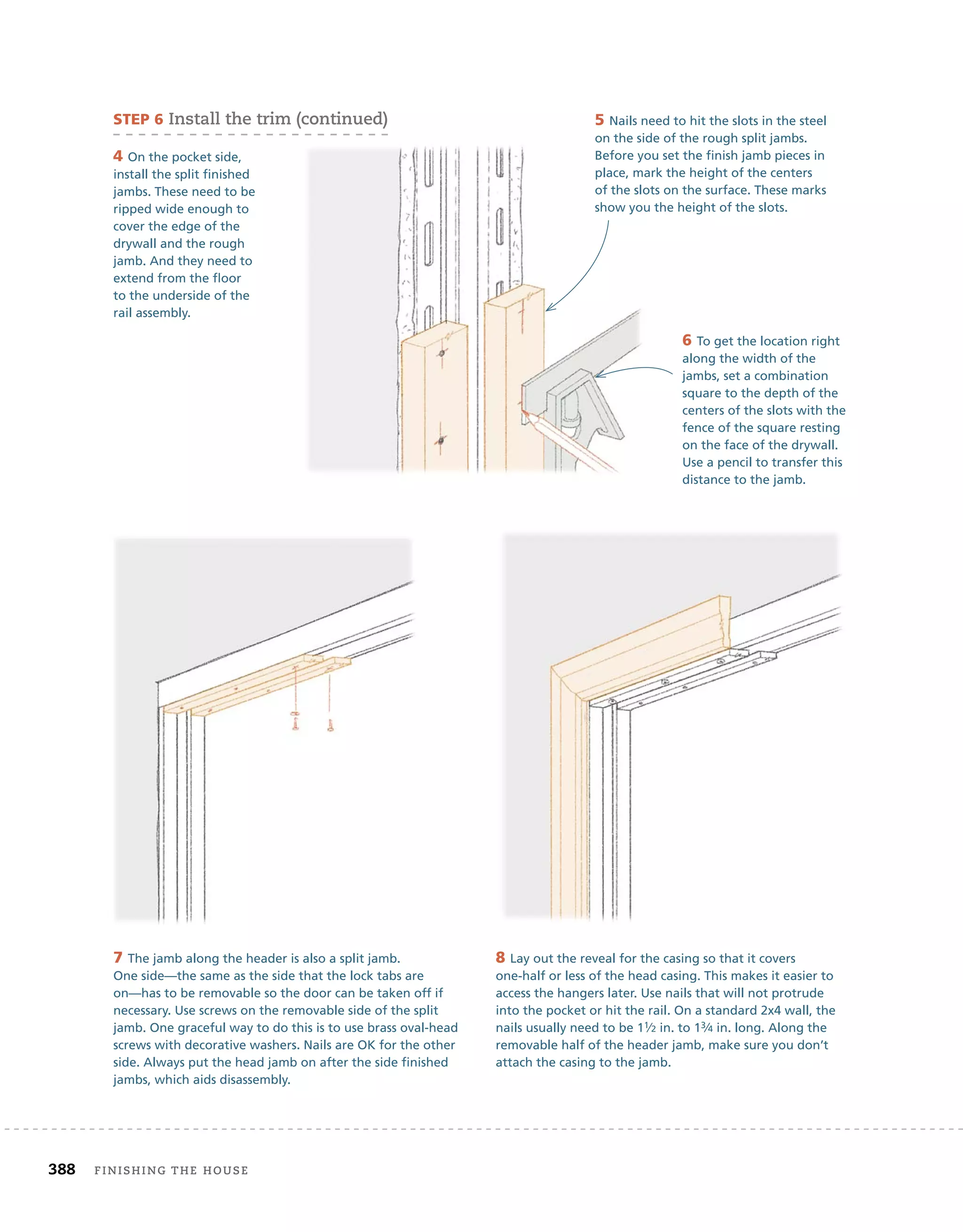

sill.[Dwgs ch10_18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24a, 24b, 25,][SB 10-6]

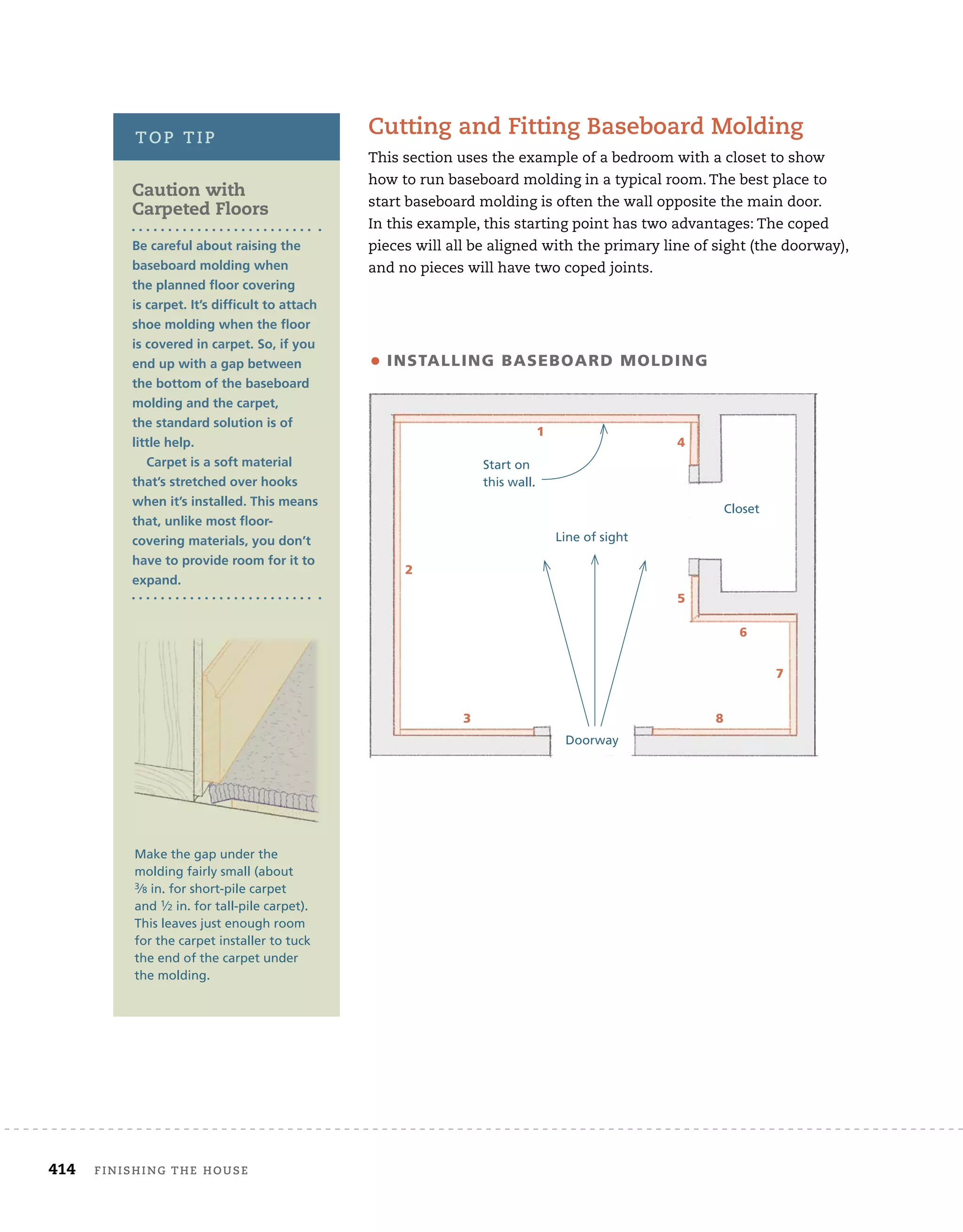

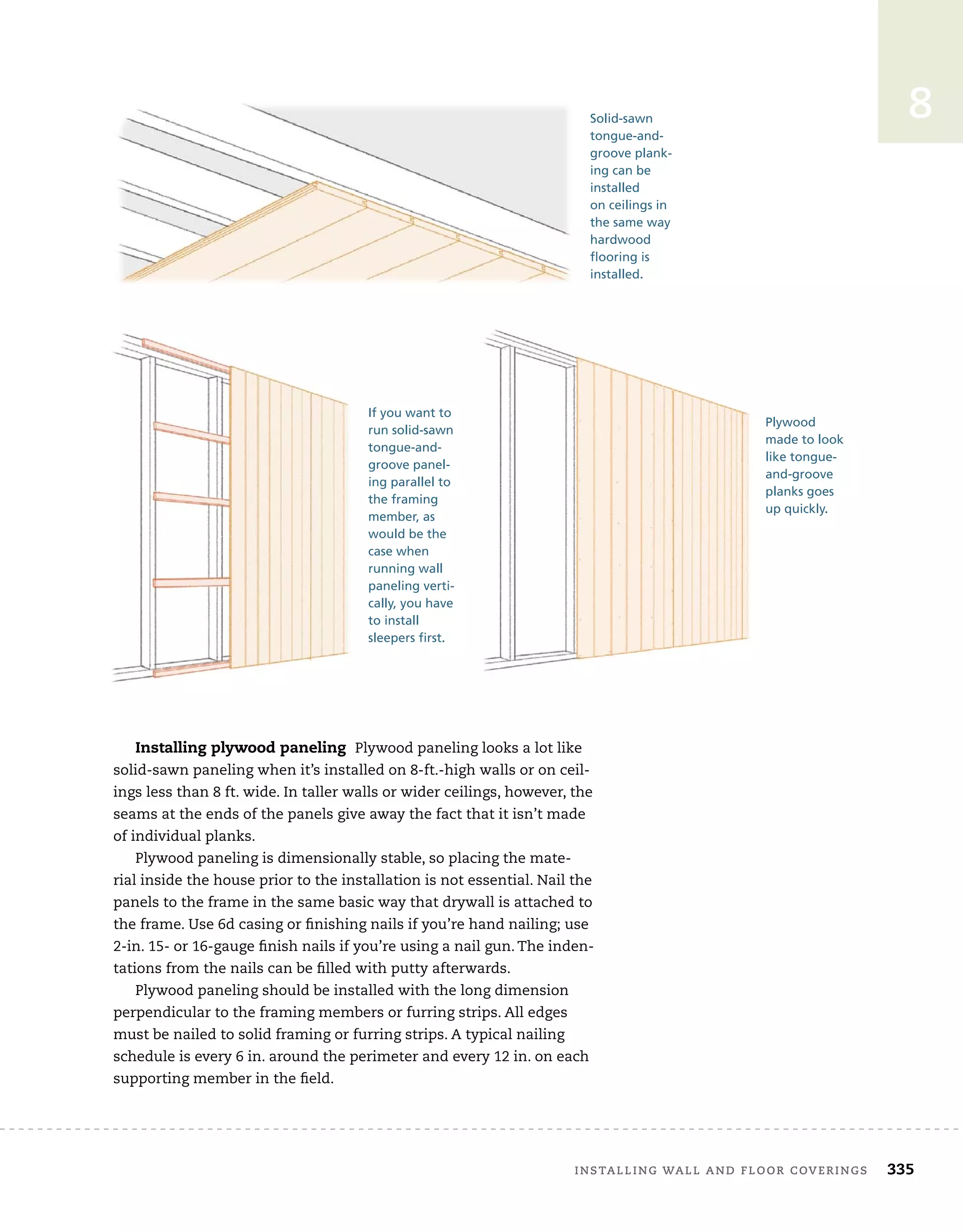

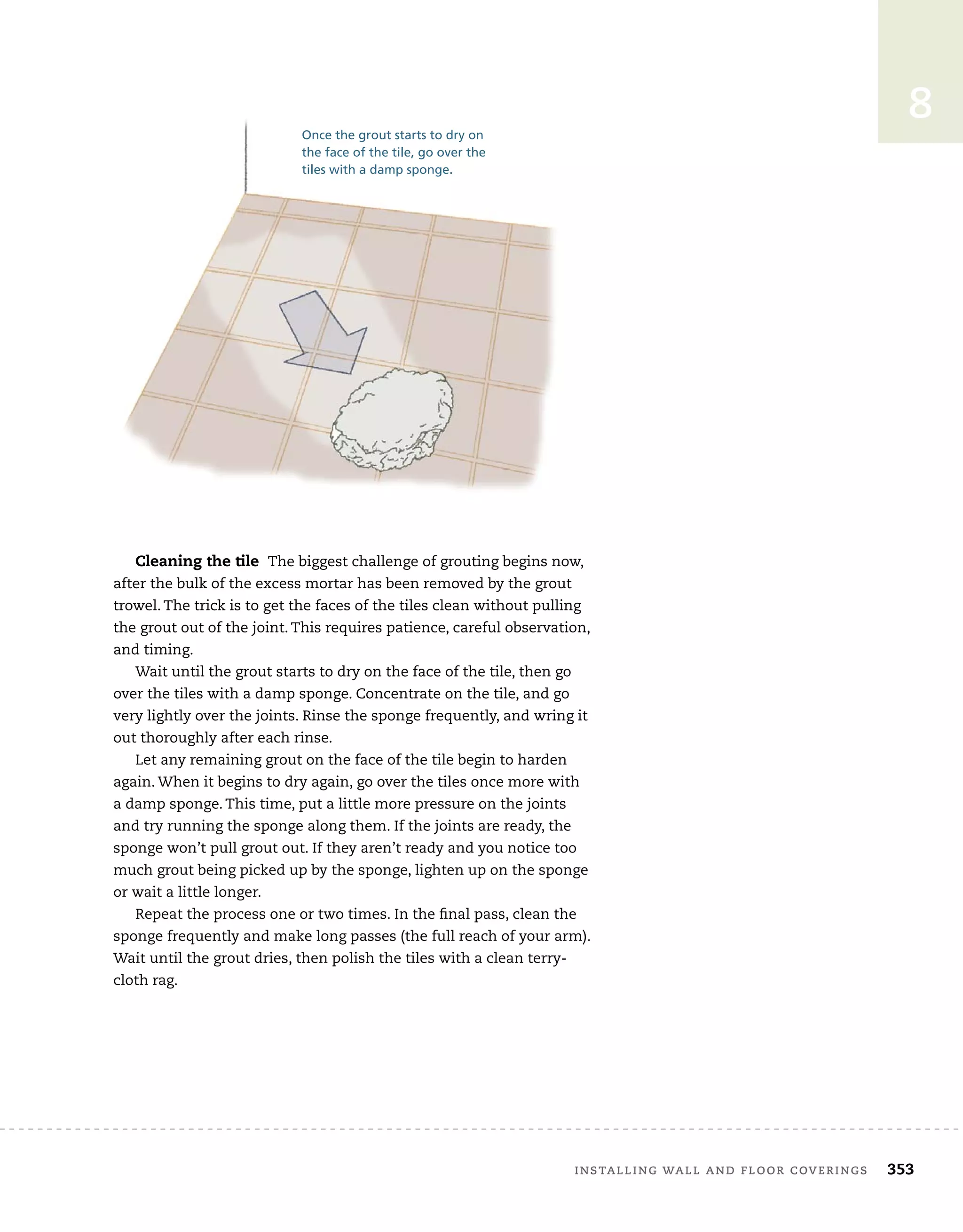

installing baseboard molding

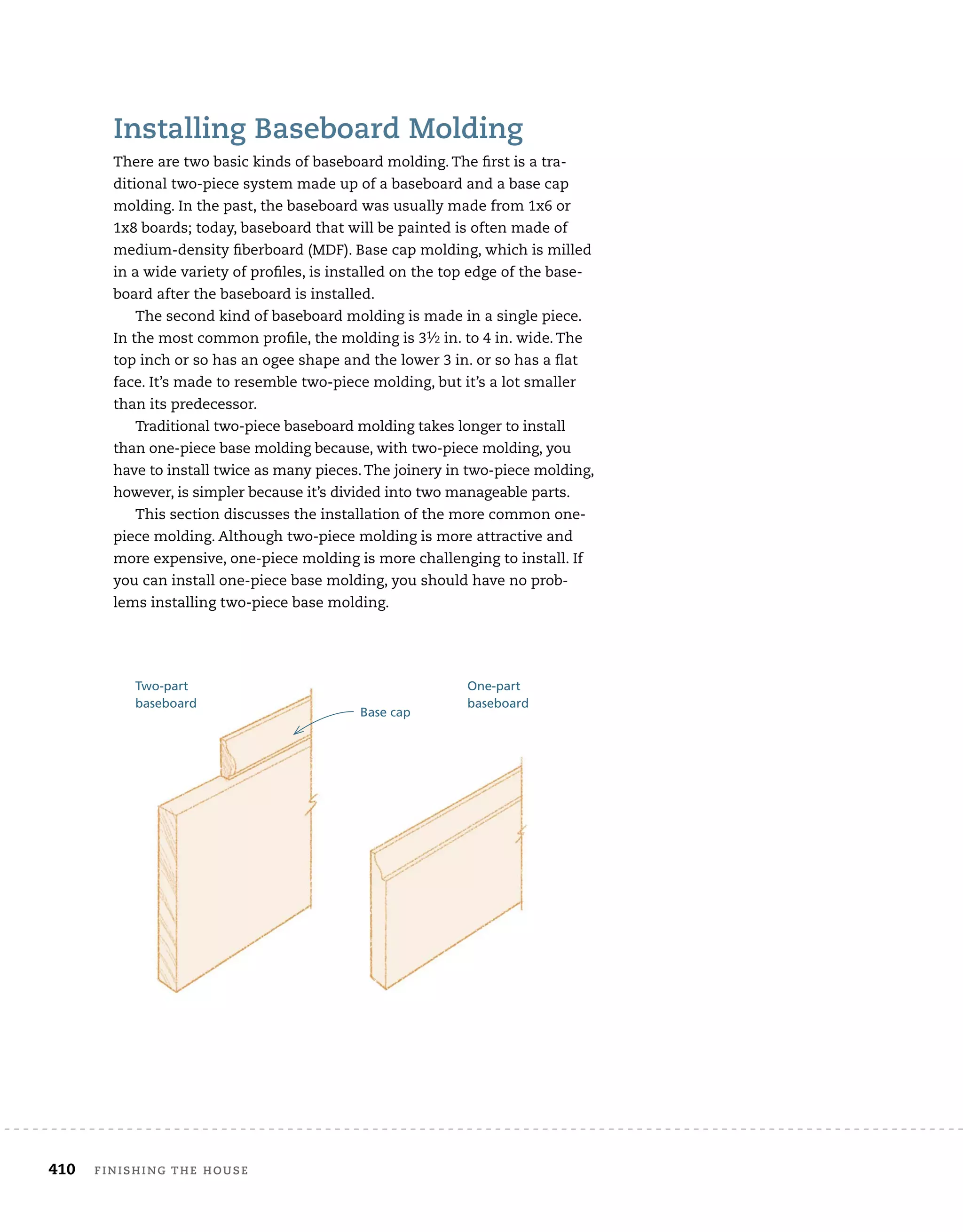

There are two basic kinds of baseboard molding. The fi

rst is a tra-

ditional two-piece system made up of a baseboard and a base cap

molding. In the past, the baseboard was usually made from 1x6 or

1x8 boards; today, baseboard that will be painted is often made of

medium-density fi

berboard (MDF). Base cap molding, which is milled

in a wide variety of profi

les, is installed on the top edge of the base-

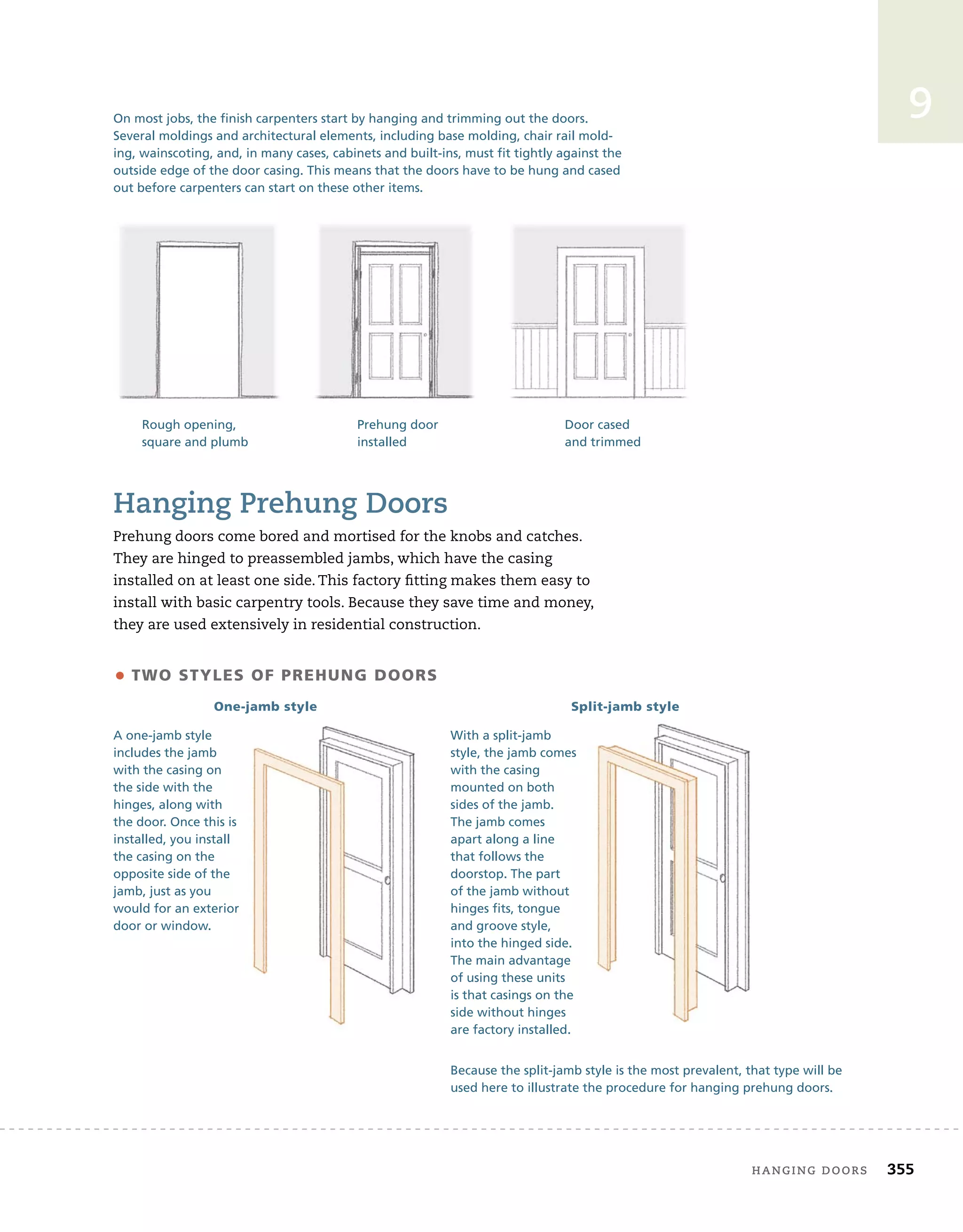

board after the baseboard is installed.

The second kind of baseboard molding is made in a single piece.

Other features and considerations

Manufacturers offer a number of other features and

accessories. These include electric brakes, digital

angle readouts, detents and highlighted marks for

common settings, laser lines, dust-collection systems,

work lights, a variety of fence configurations, clamp-

ing systems, and stops. Make sure you consider the

weight of the saw and how much noise it makes. This

information can be found in comparative tool reviews,

tool catalogs, and on Web tool sites. You can also

check the specifications provided online by individual

tool manufacturers.

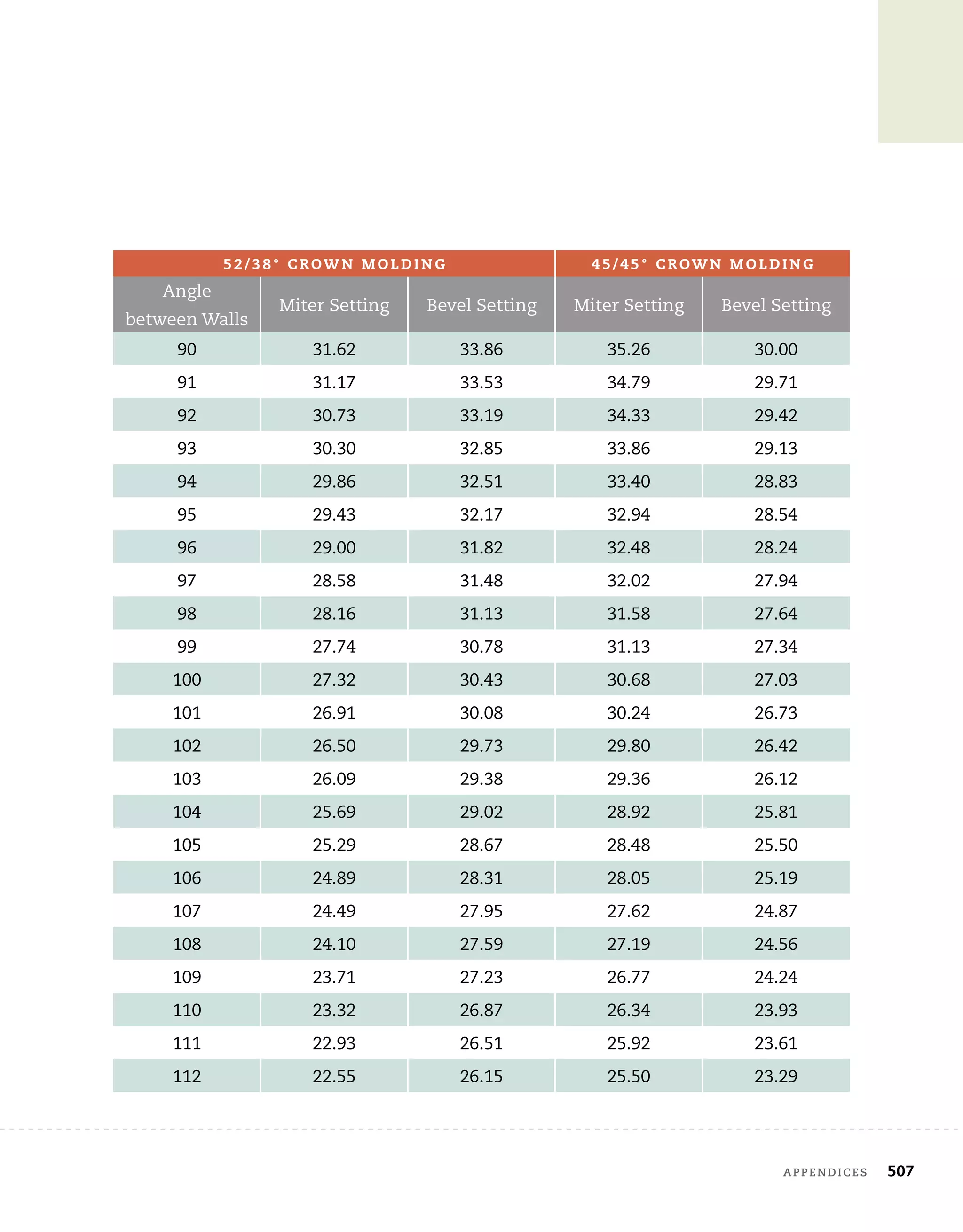

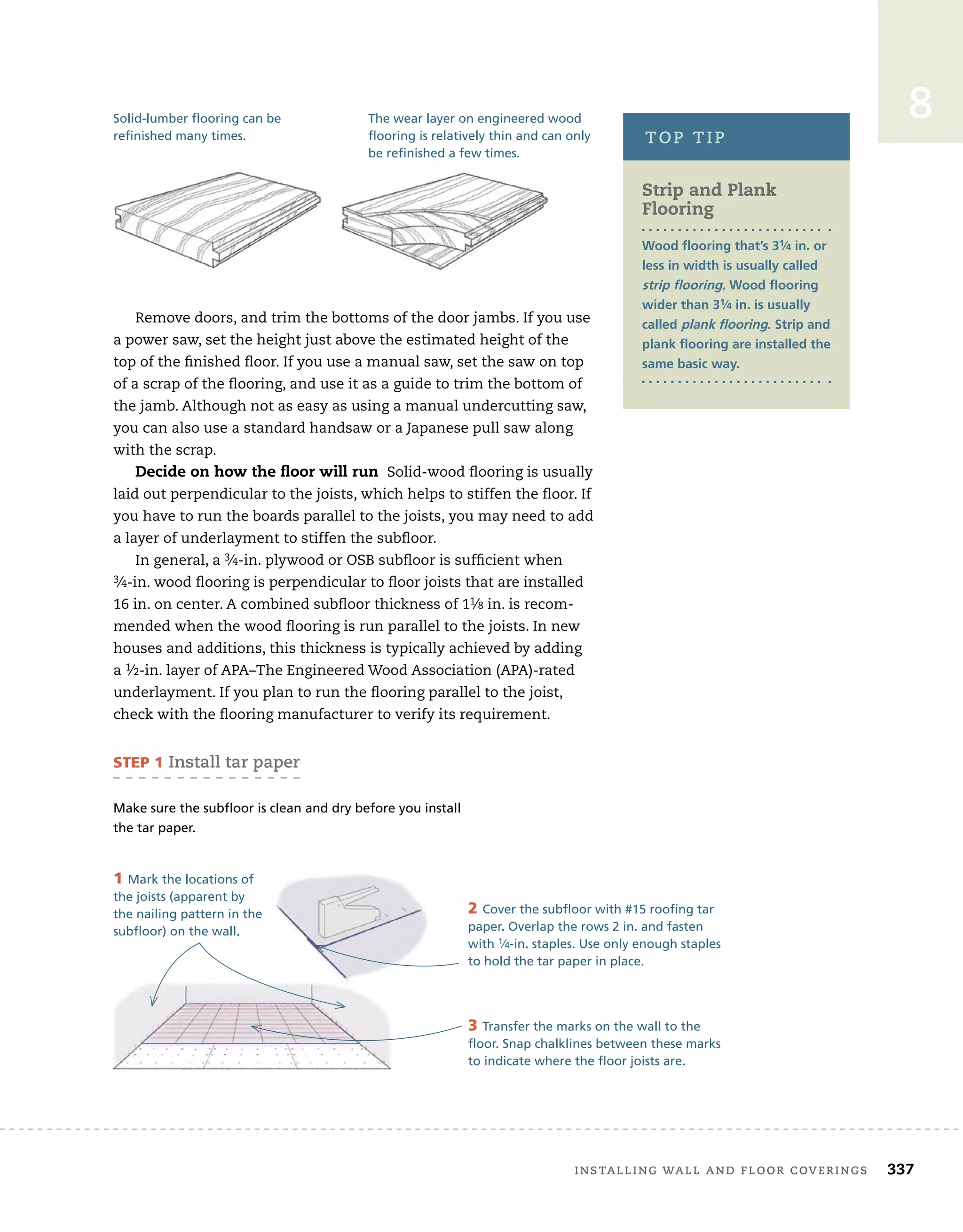

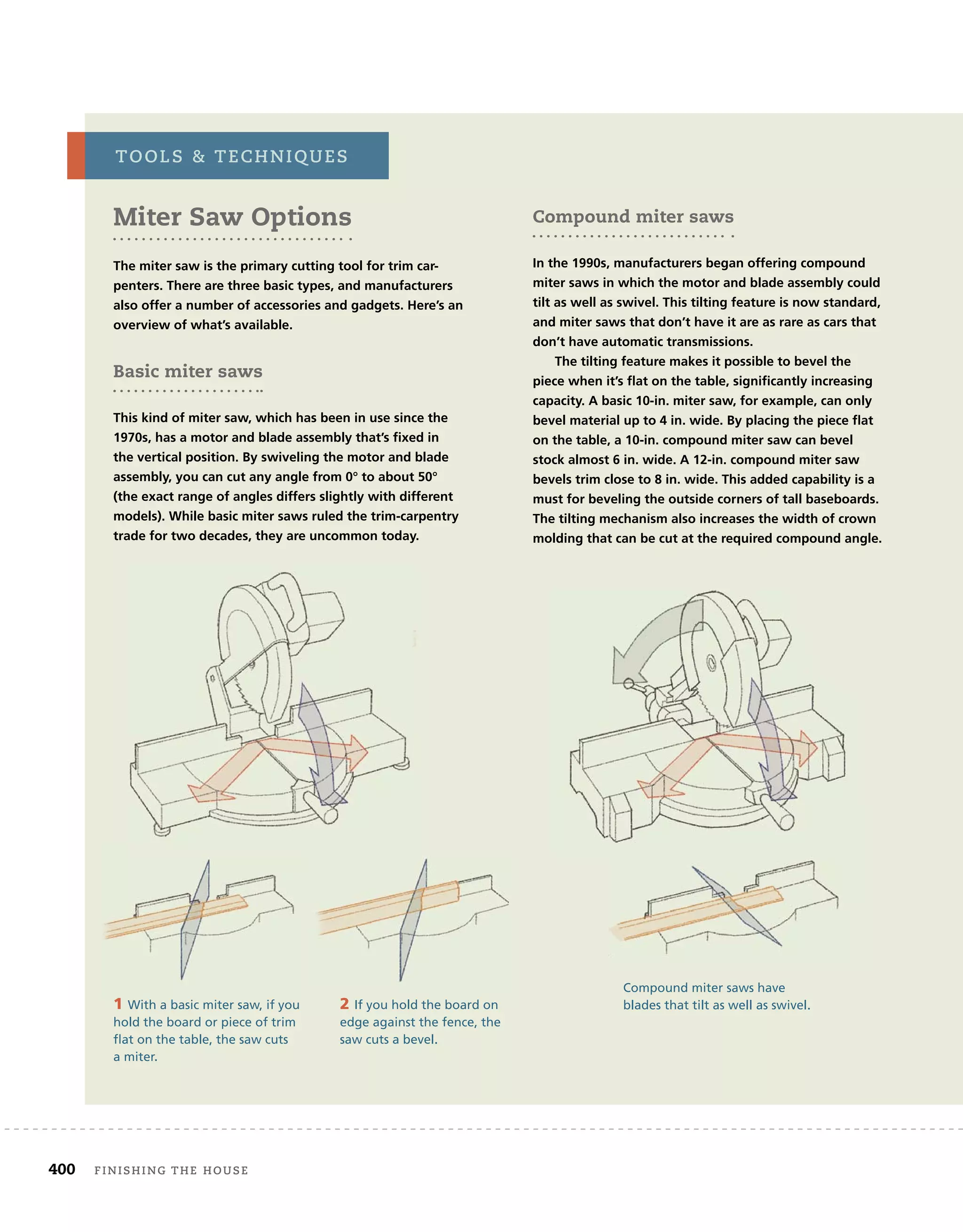

Sliding compound miter saws

Costing about twice as much as a compound miter saw,

the sliding compound miter saw (SCMS) has a much

larger cutting capacity. On these saws, the motor and

blade assembly is mounted on an arm. By sliding the

assembly along the arm, it’s possible to make very long

yet precise cuts.

Most SCMS are capable of crosscutting boards that

are 12 in. wide. And they’re capable of making compound

miter/bevel cuts at 45°/45° in material that’s 8 in. wide.

Because of its long cutting capacity, the SCMS is also a

great tool for making the compound miter cuts required

for hip and valley roofs.

A 10-in. sliding compound miter saw

can precisely cut just about any base or

crown molding or crosscut shelves

and stair-tread material.

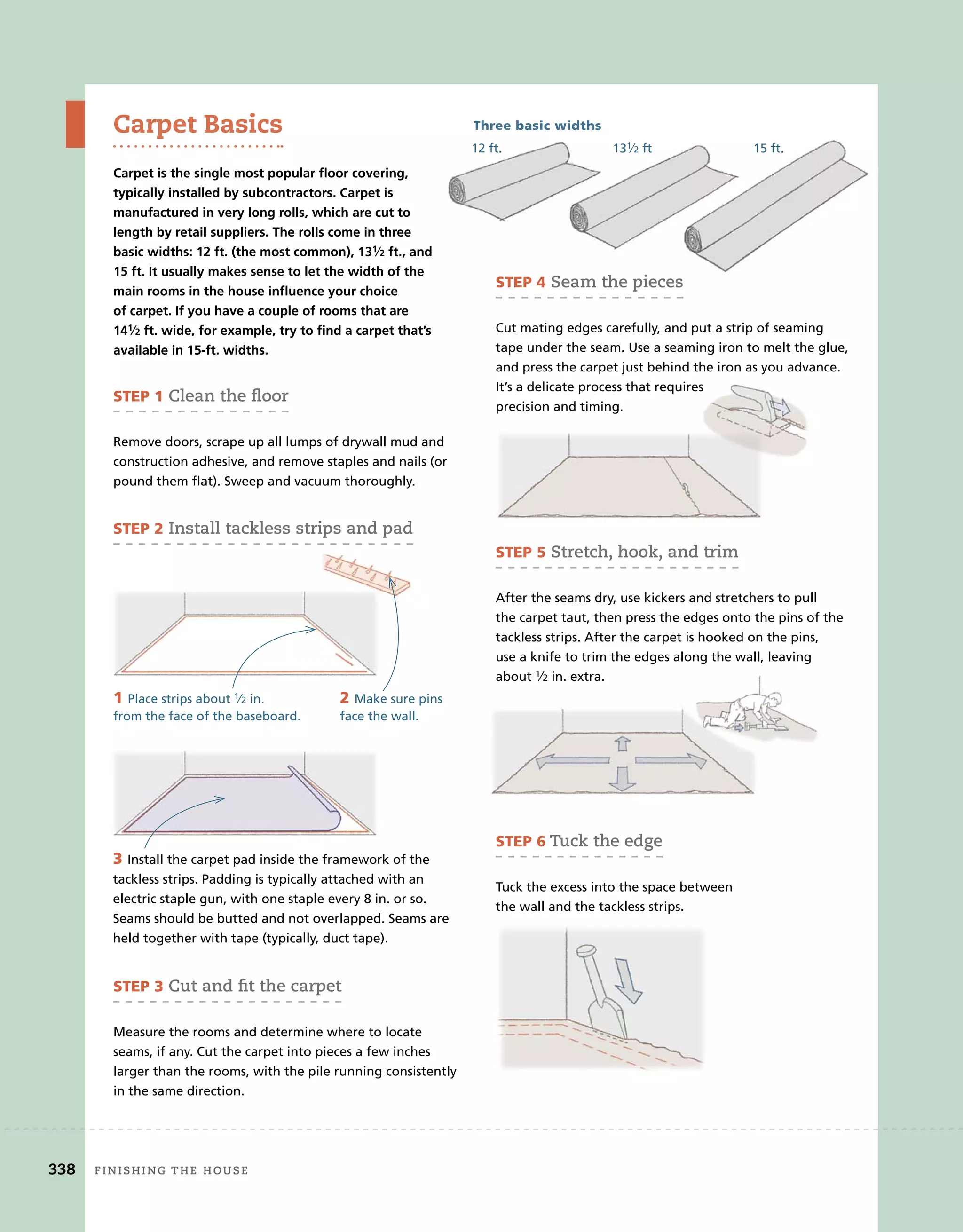

A dual-bevel feature adds to the cost of

the saw, but it’s well worth the money if you

expect to install a lot of crown molding or

build complex roofs.

Dual-bevel feature

By repositioning the motor and handle of their

saws, some manufacturers now offer compound

miter saws and SCMS that can be tilted to the right

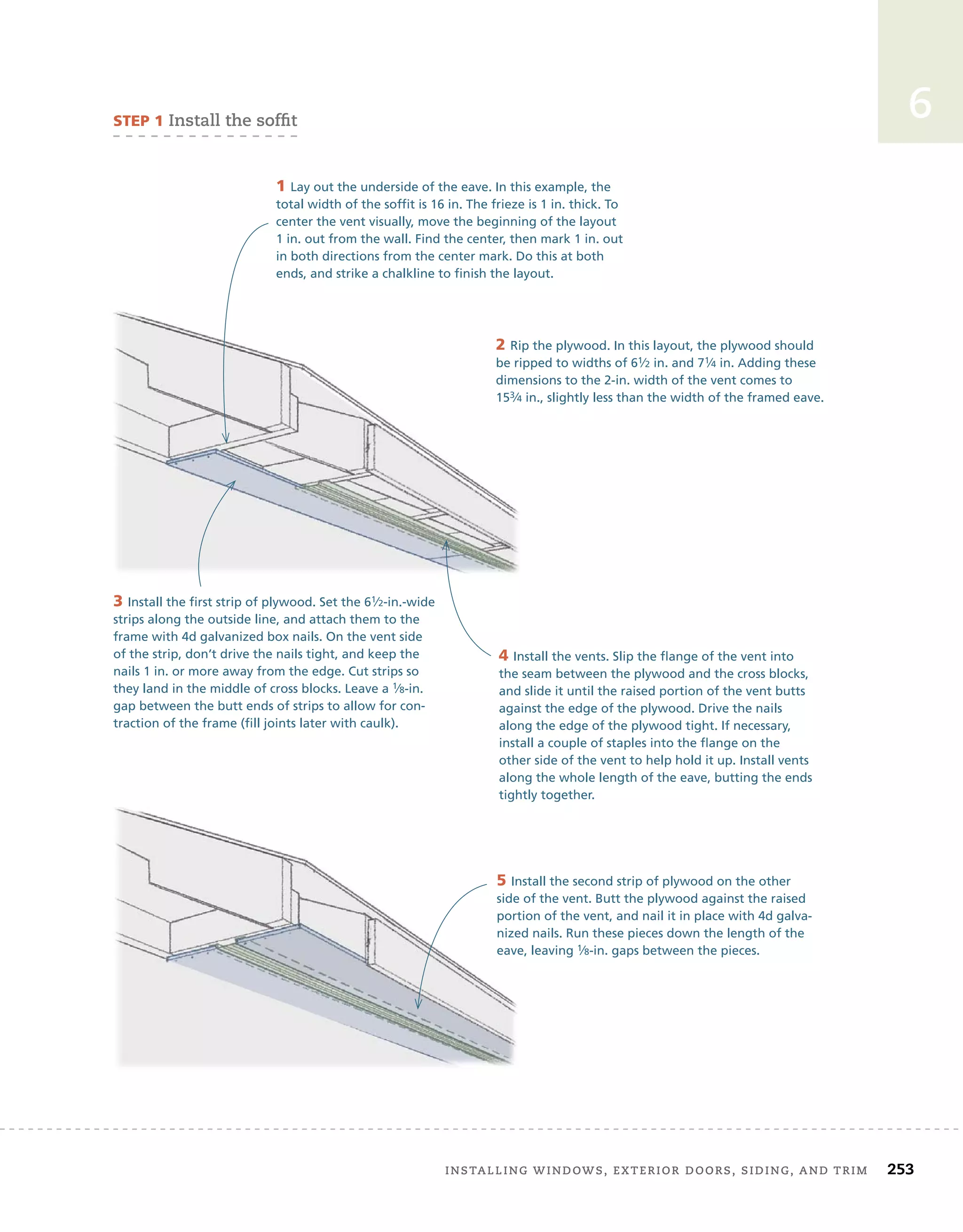

or the left.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thecompletevisualguidetobuildingahouse-220415183916/75/The-Complete-Visual-Guide-To-Building-A-House-pdf-408-2048.jpg)