This research investigates consumer attitudes and purchase intentions regarding organic food in the UK, noting the growing significance of the organic food market, which has expanded beyond a niche market due to consumer demand and wider availability in various retail outlets. Key factors influencing purchase intentions include organic certification labels, health and environmental concerns, and price, with findings indicating price remains a barrier for consumers. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of consumer knowledge as a determinant of their attitudes towards organic products, suggesting enhanced public education on organic food could bolster market growth.

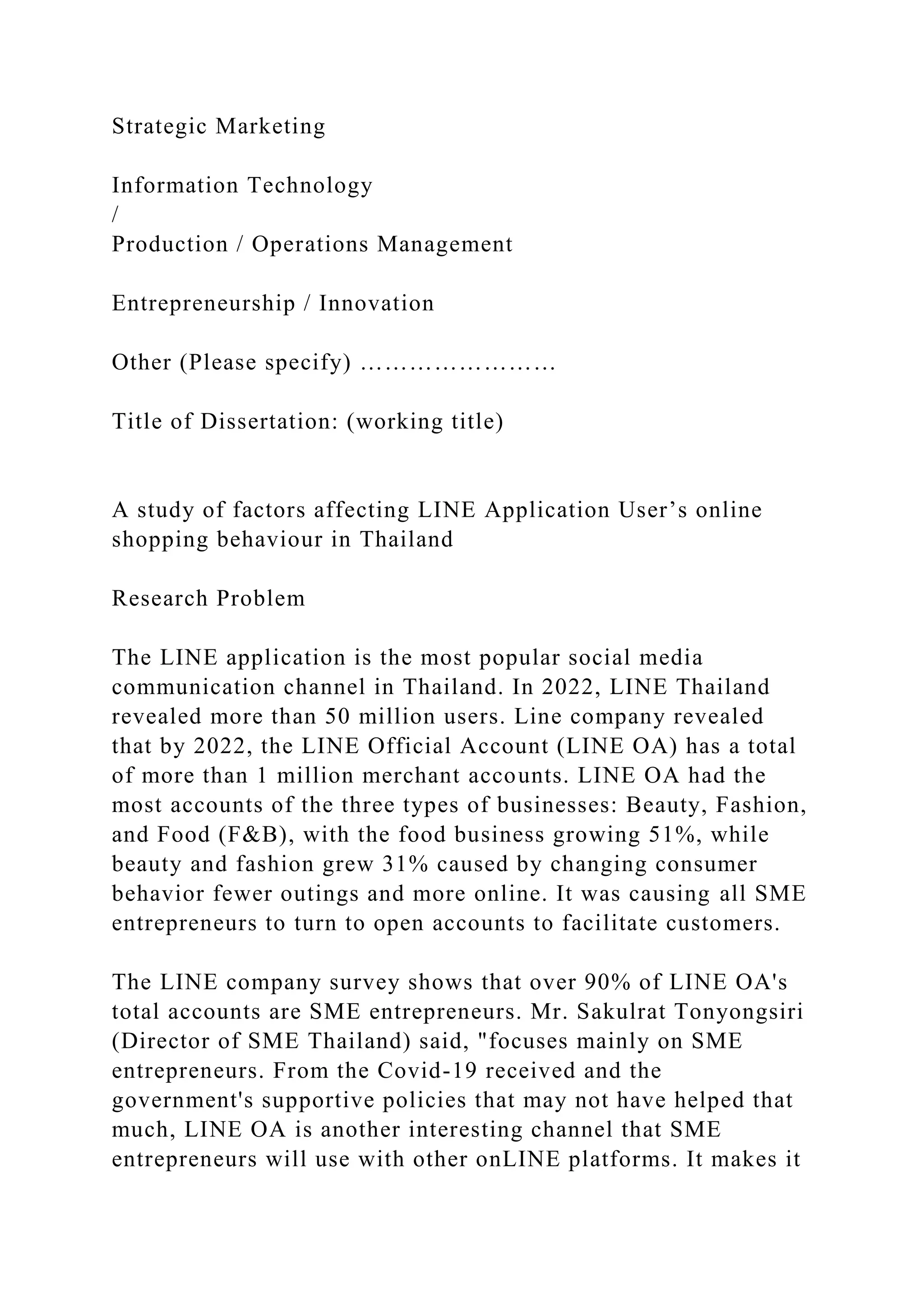

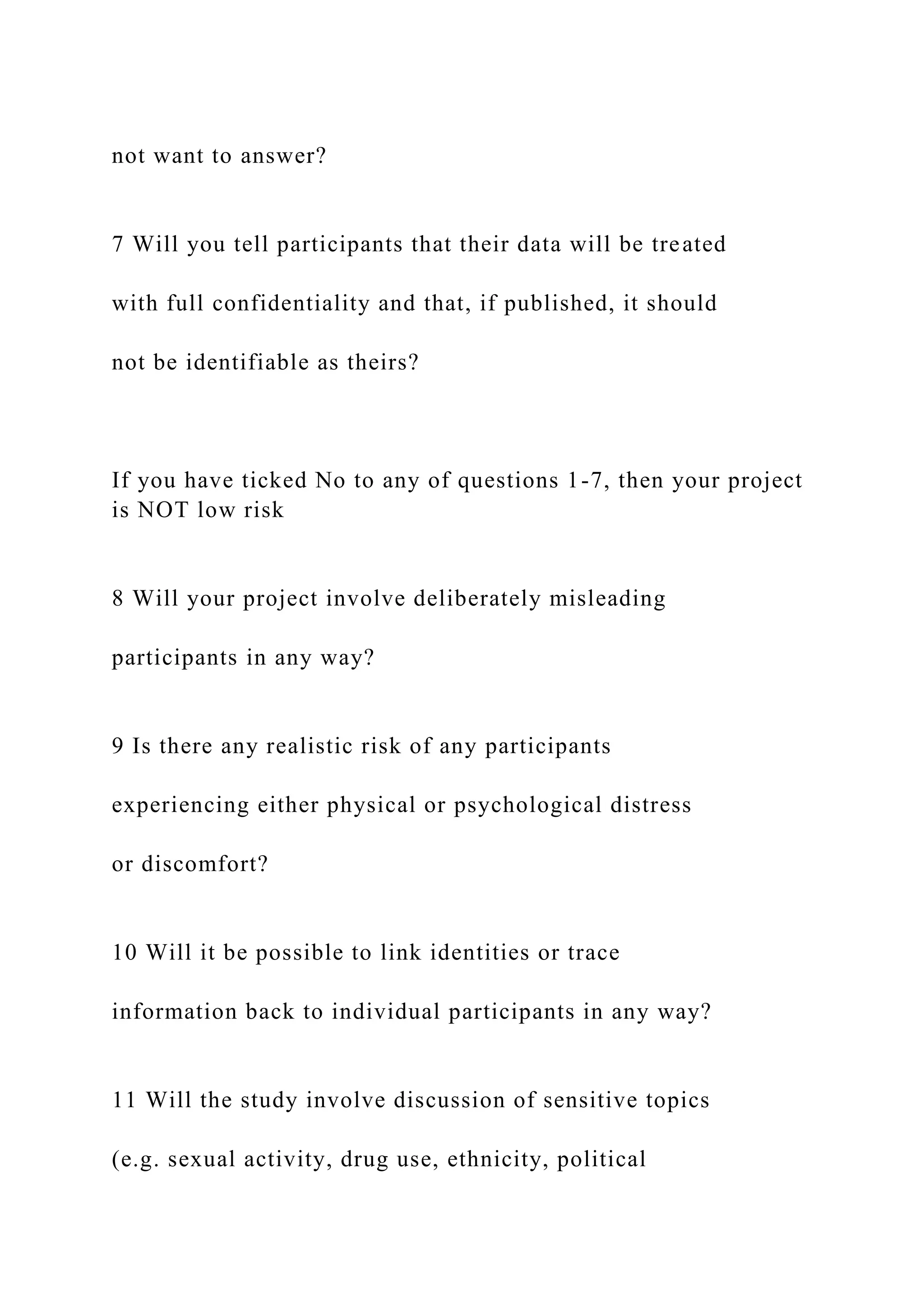

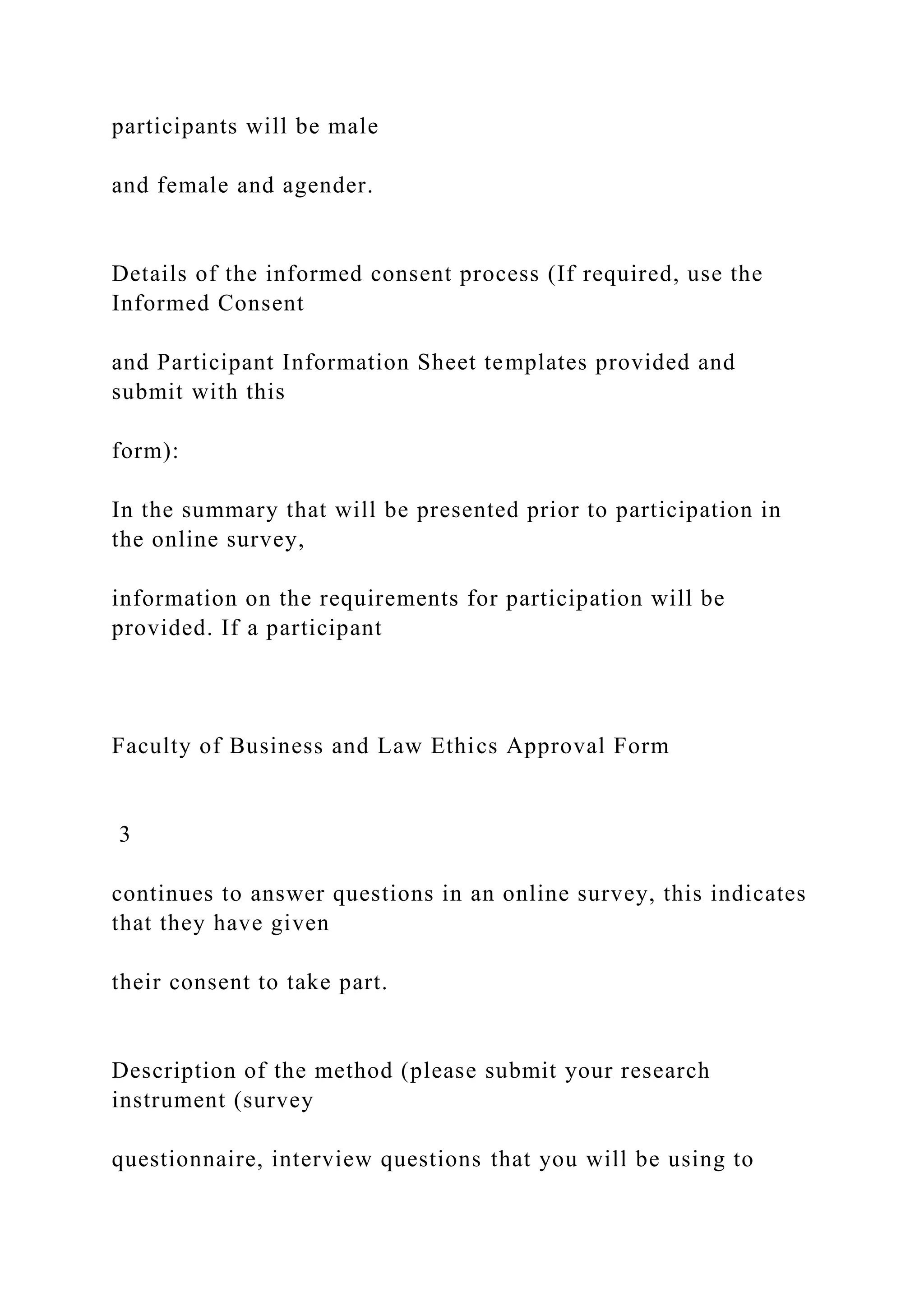

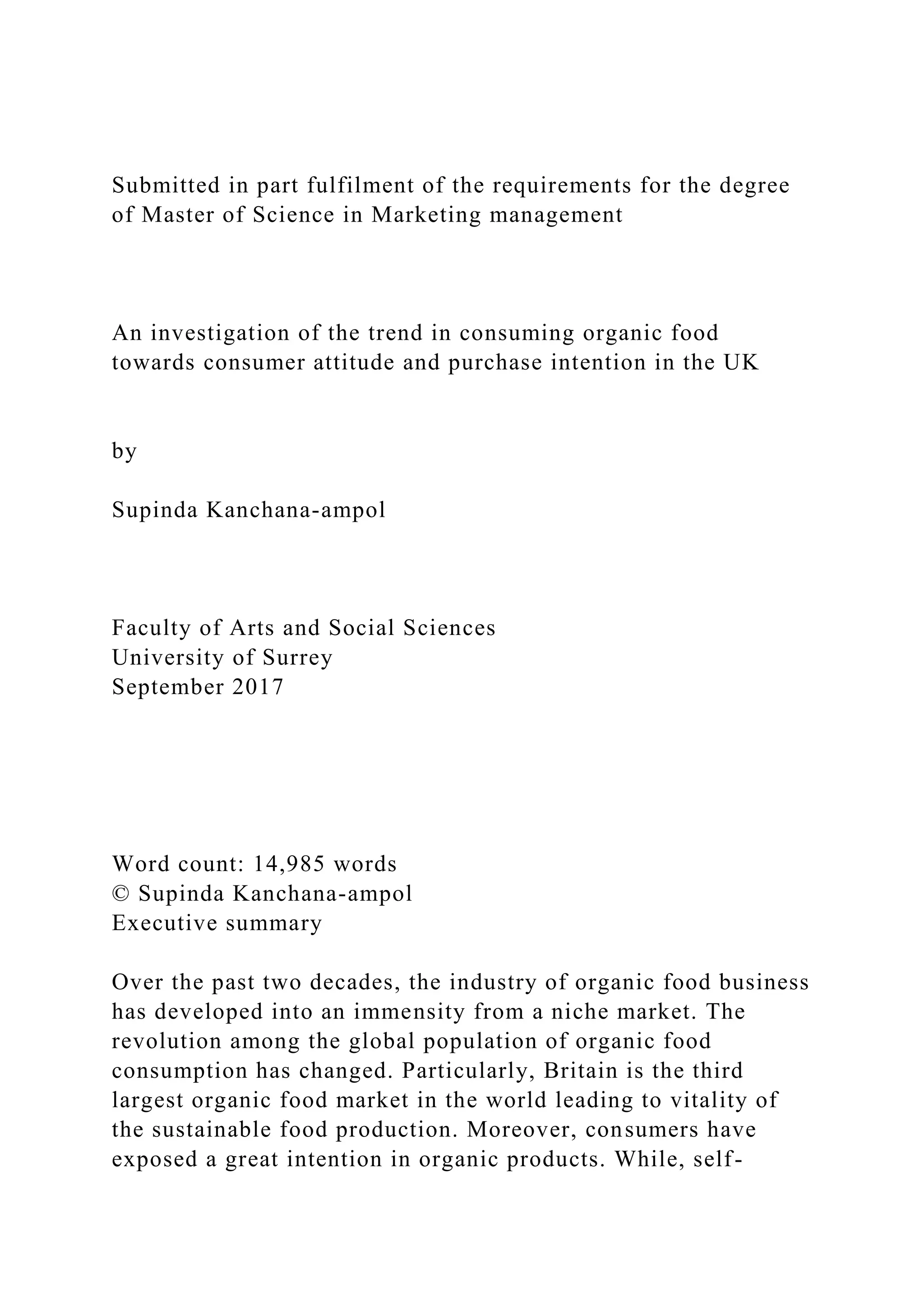

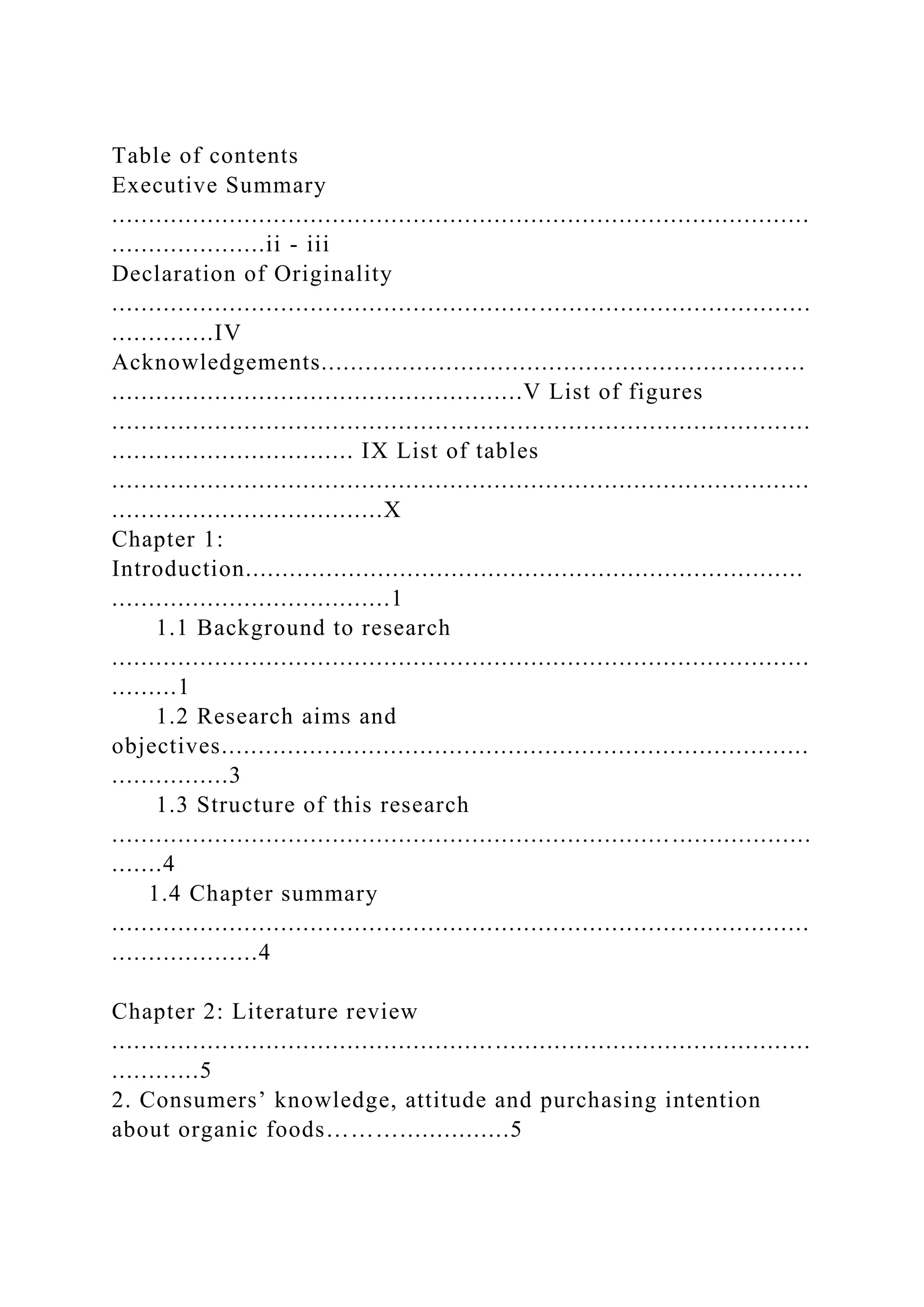

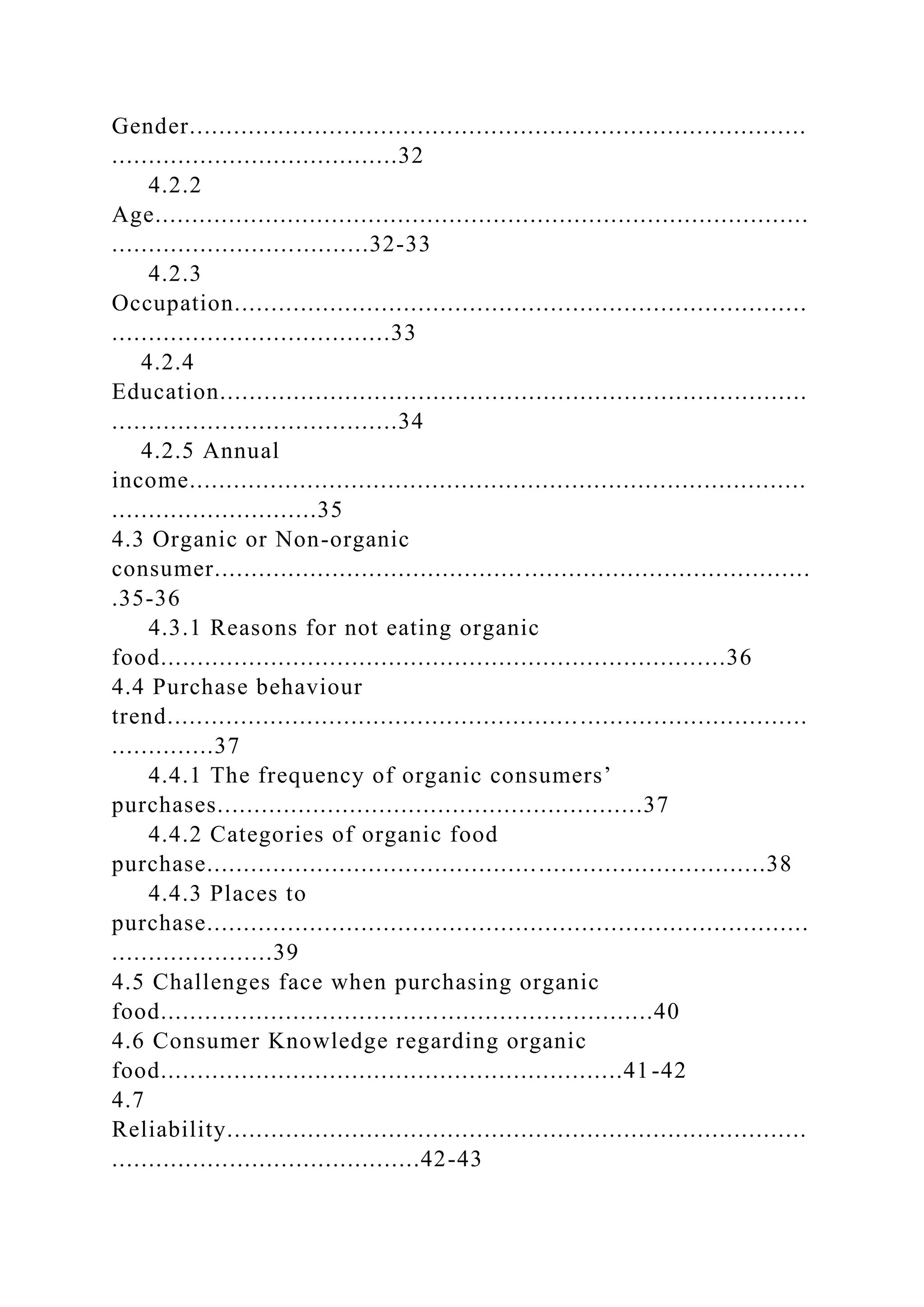

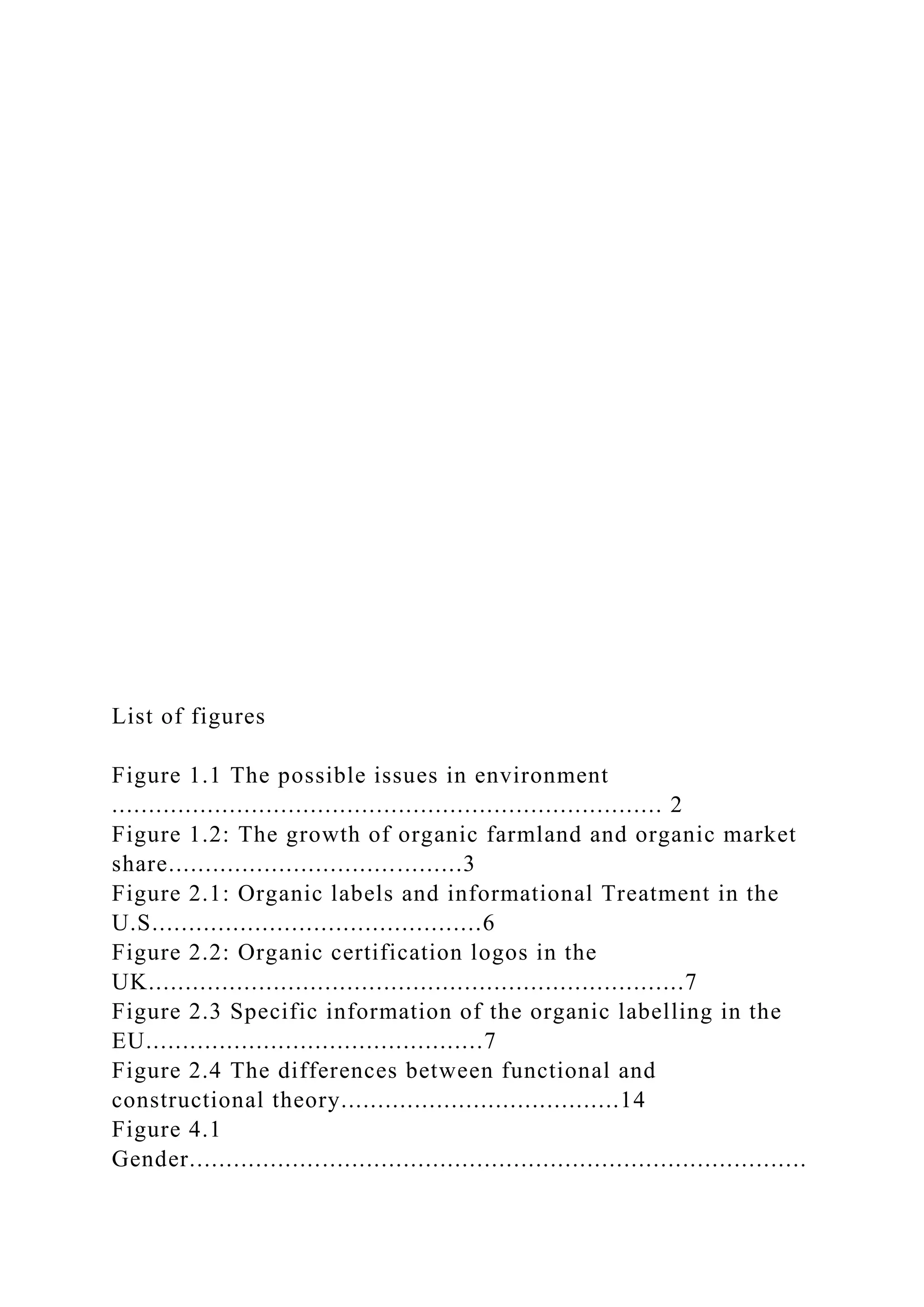

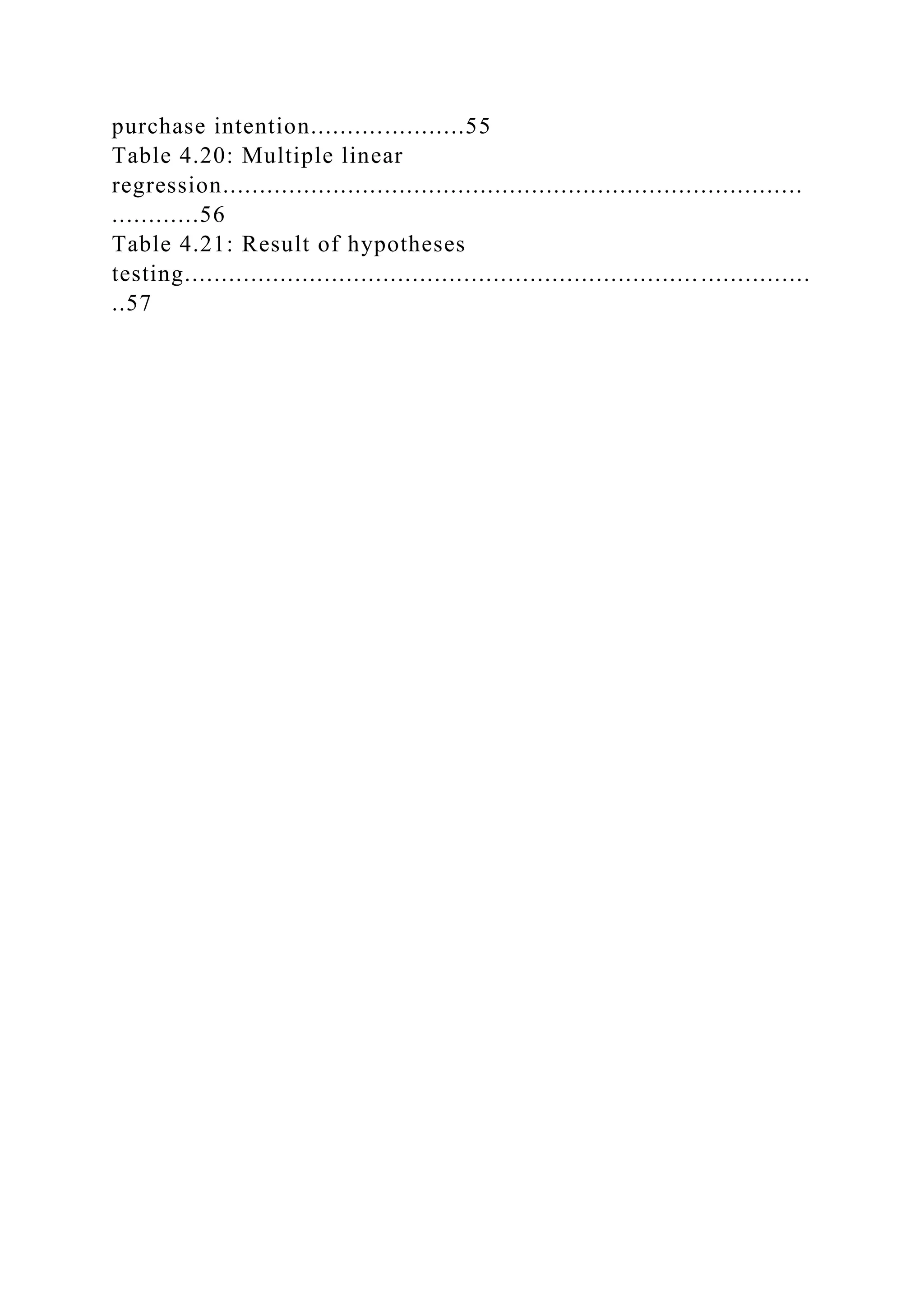

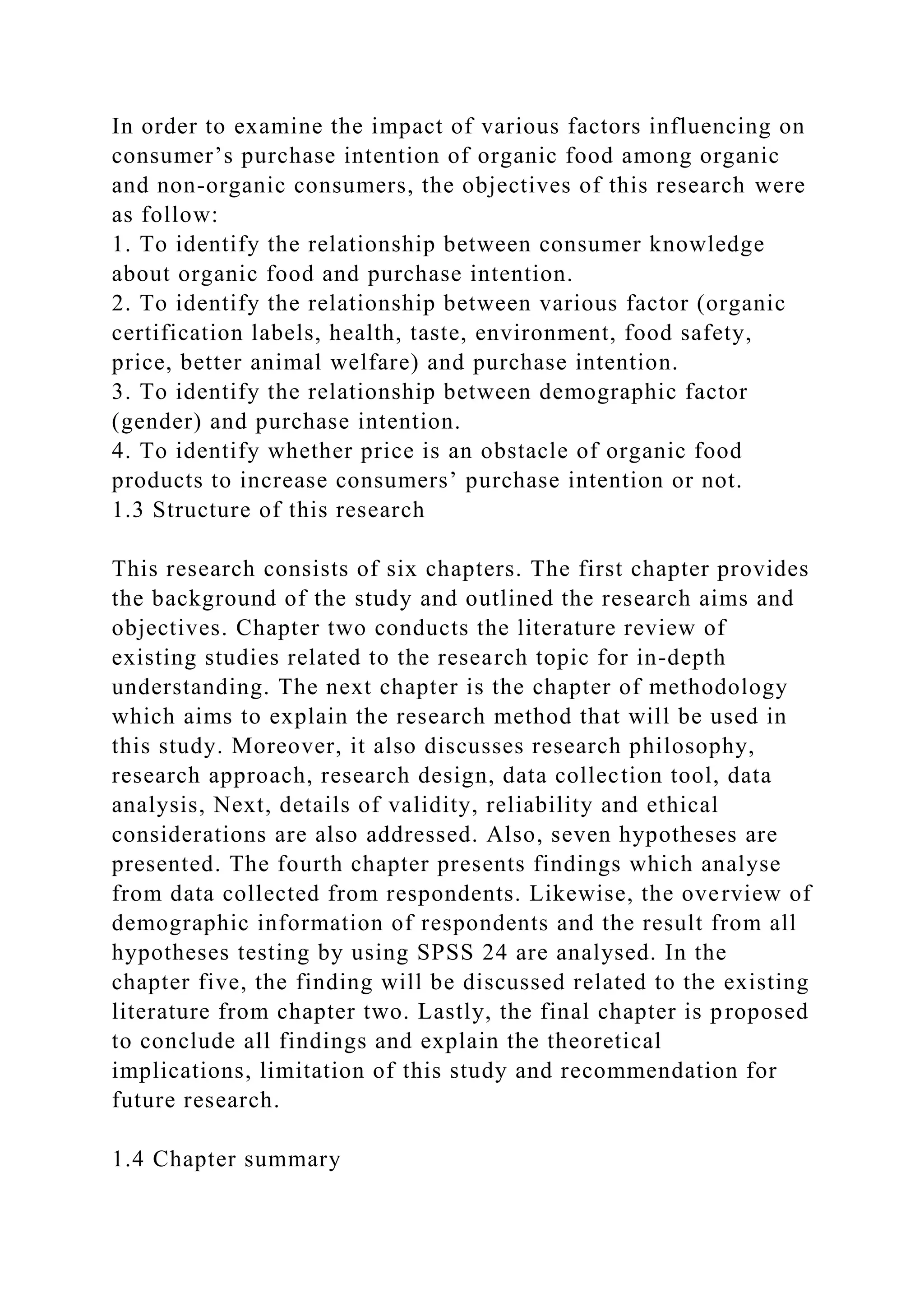

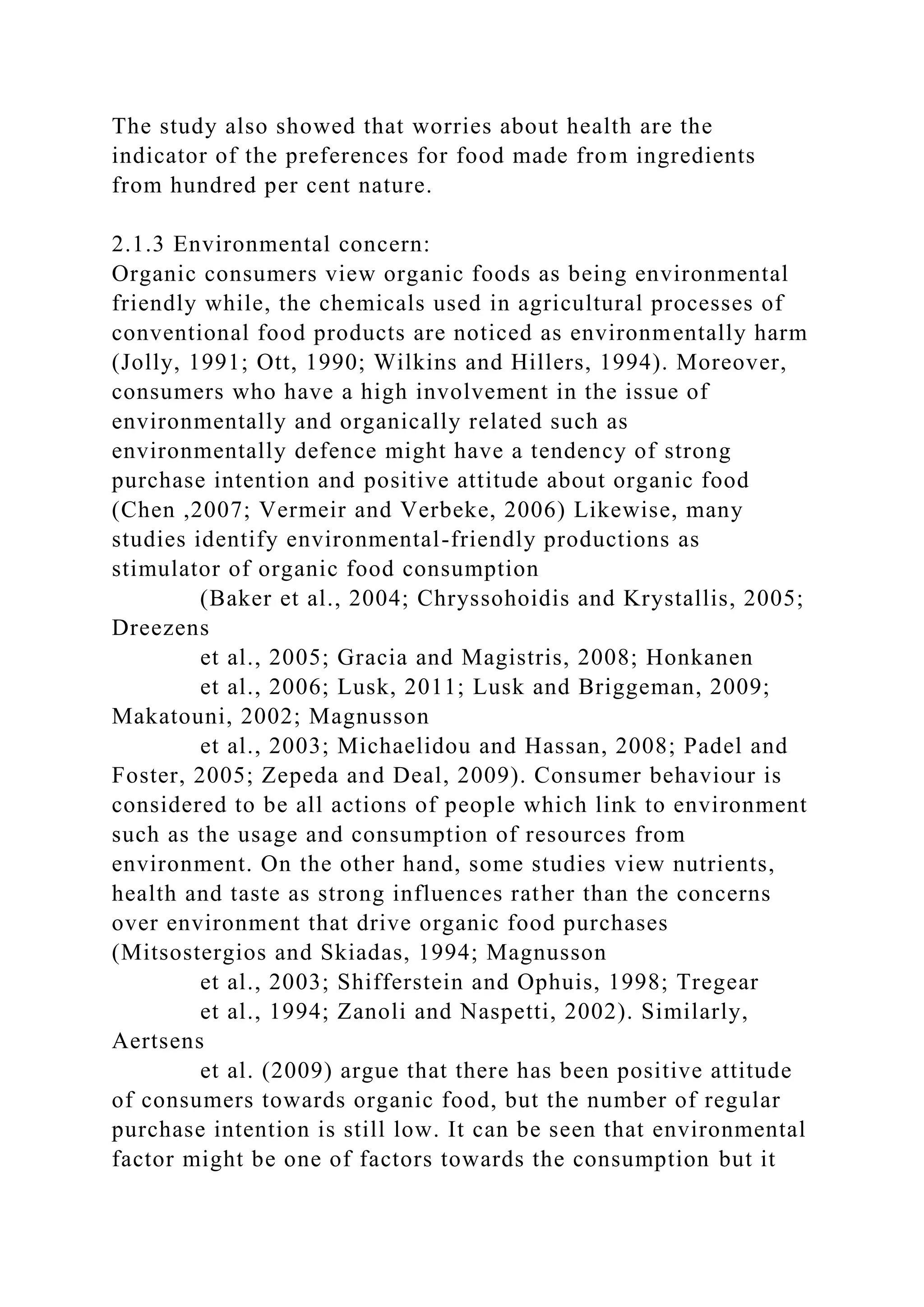

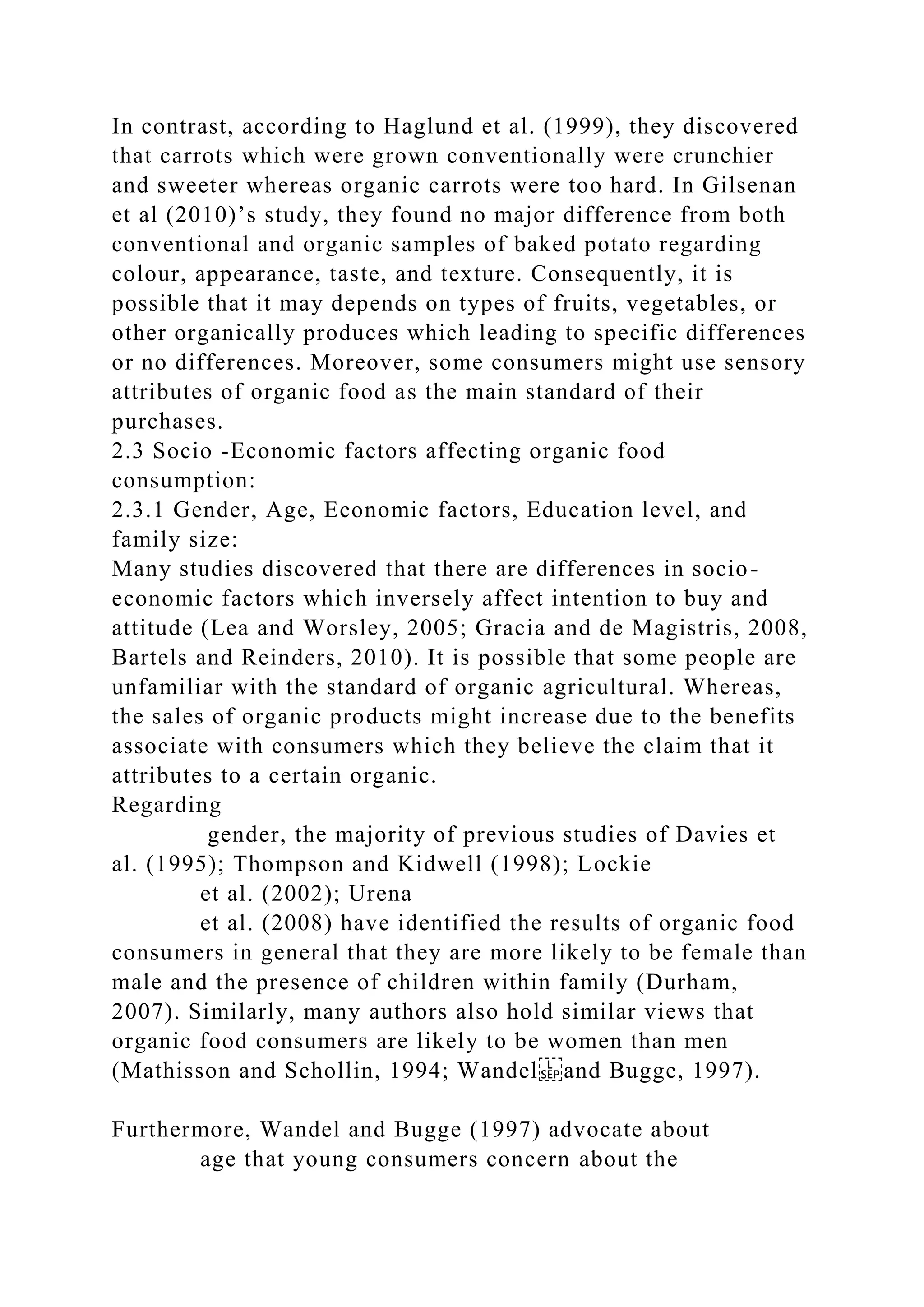

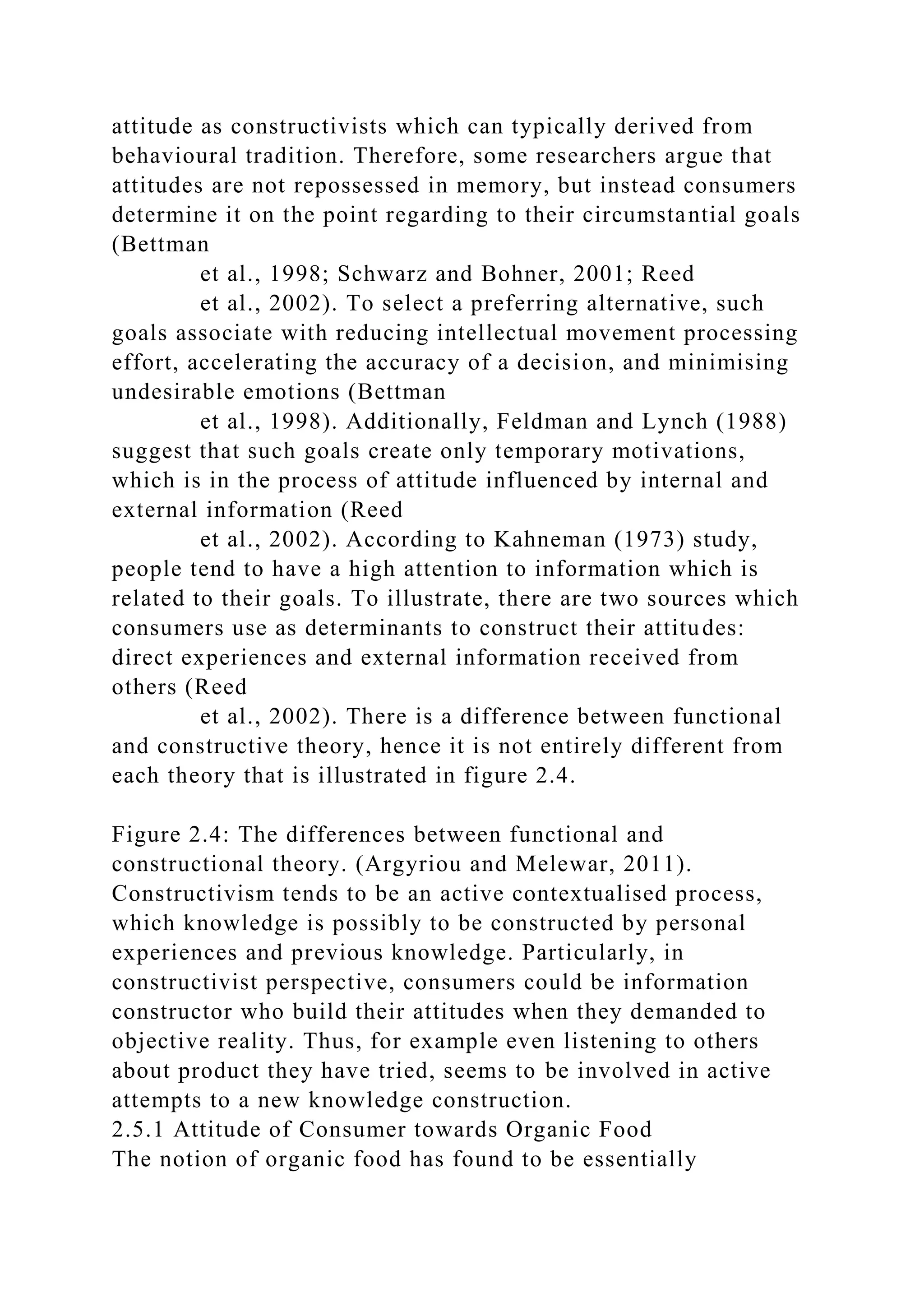

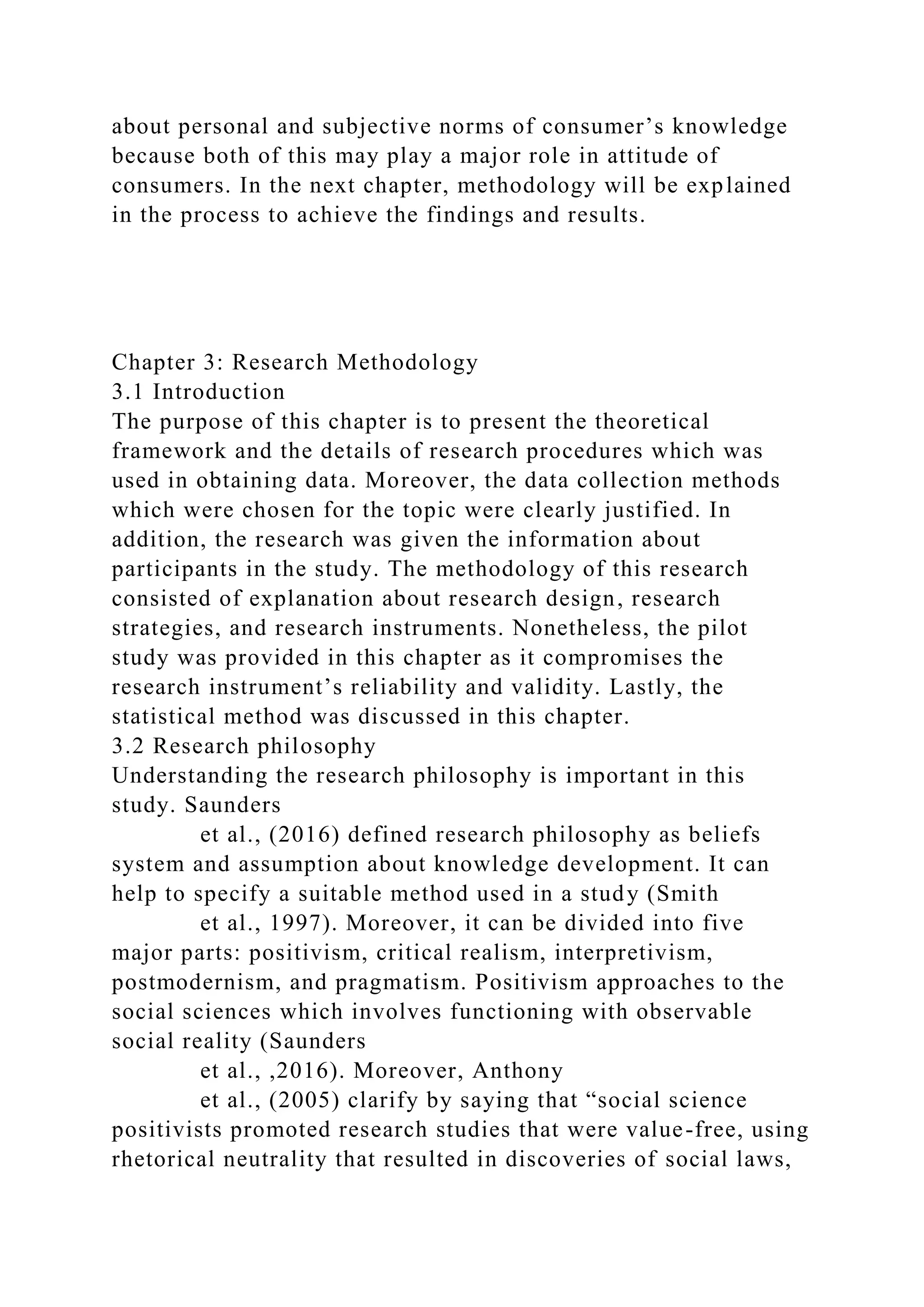

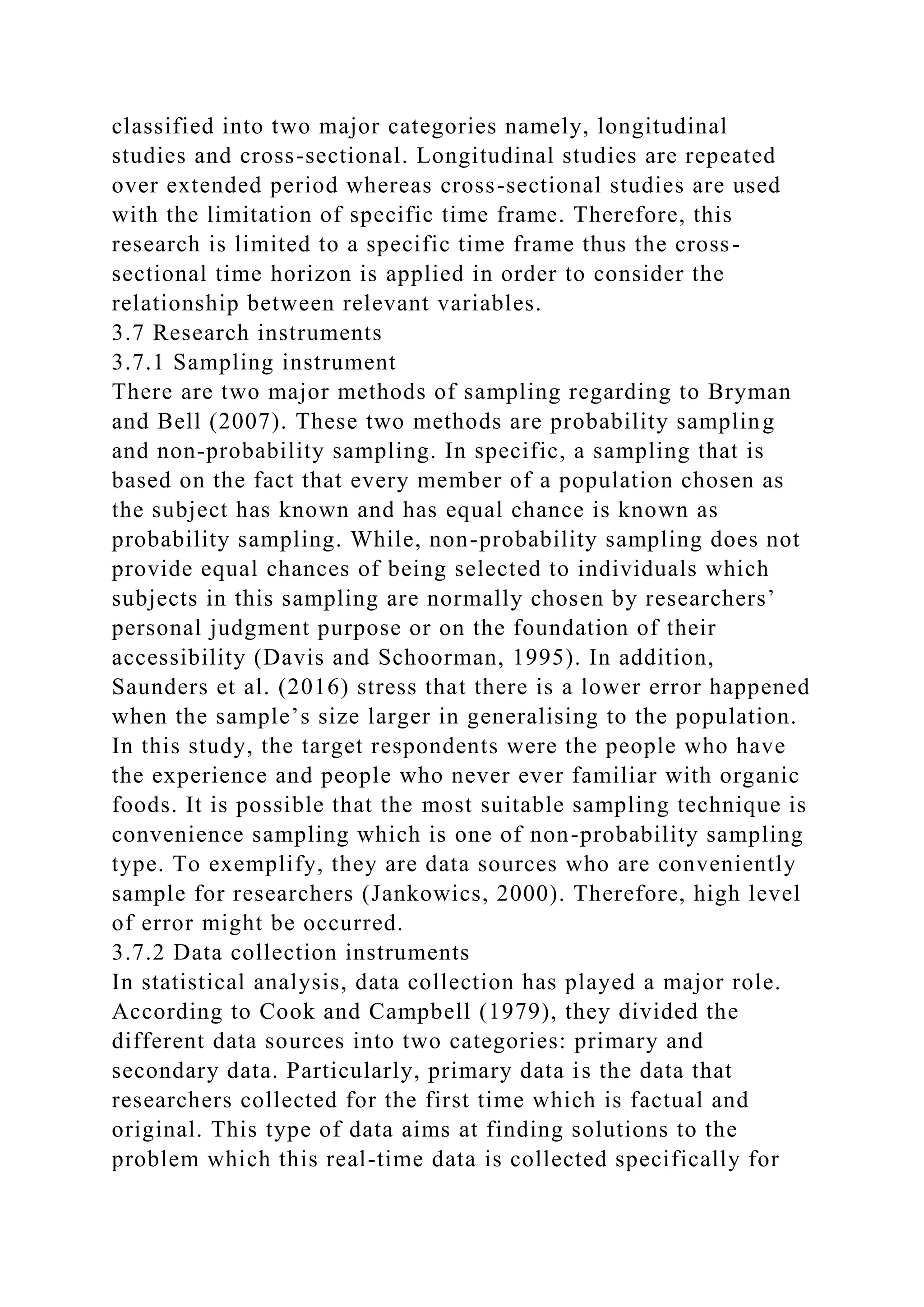

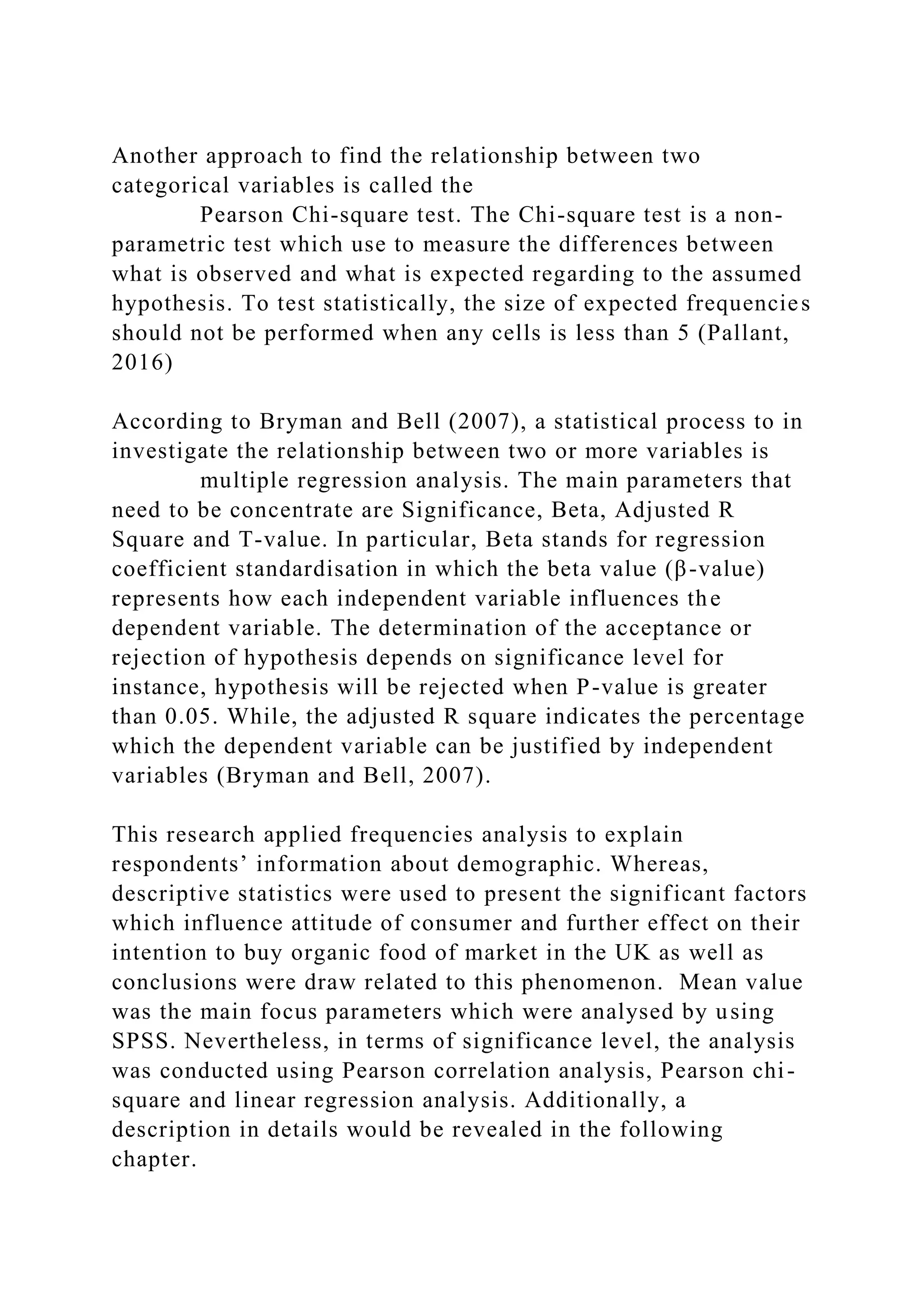

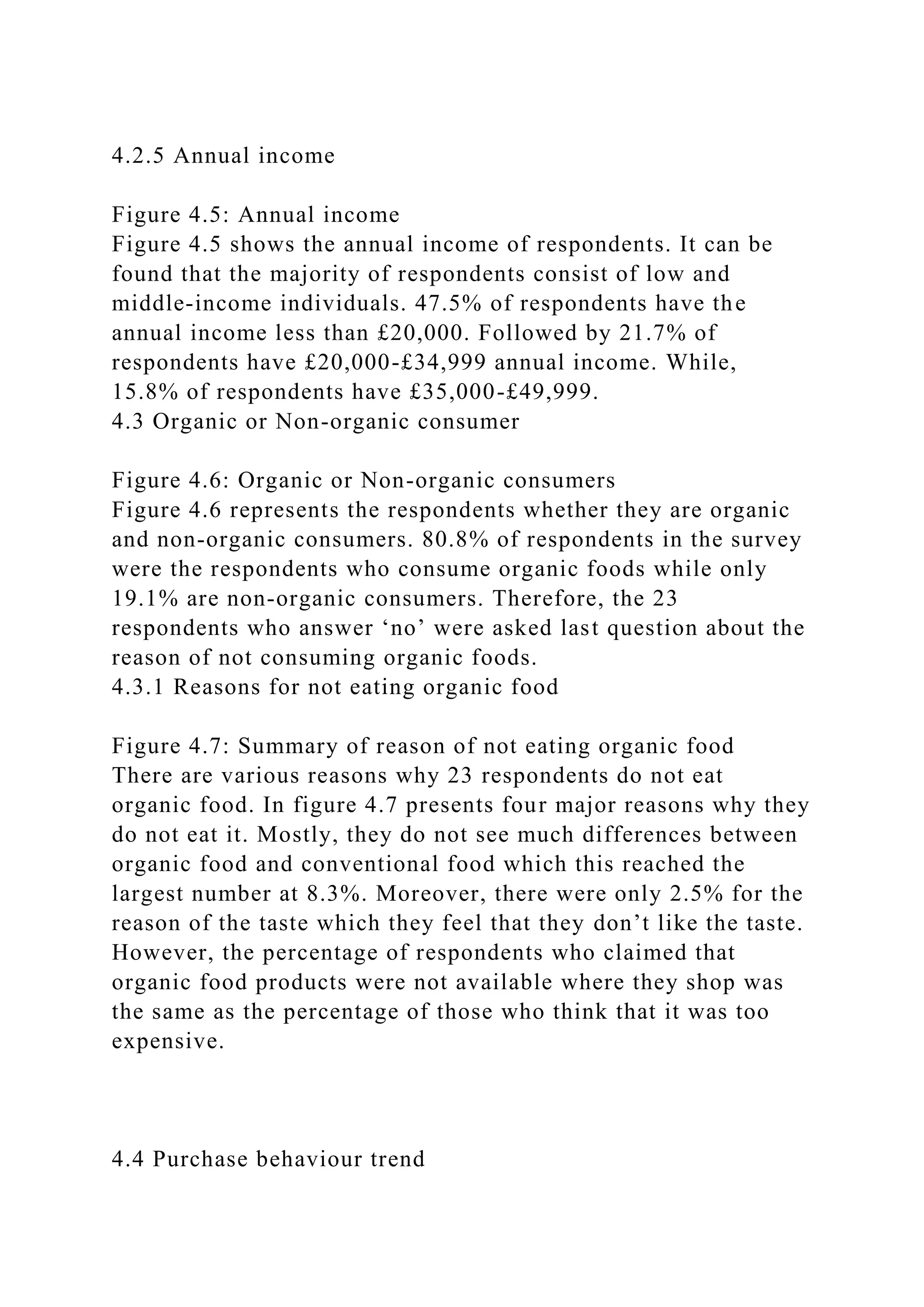

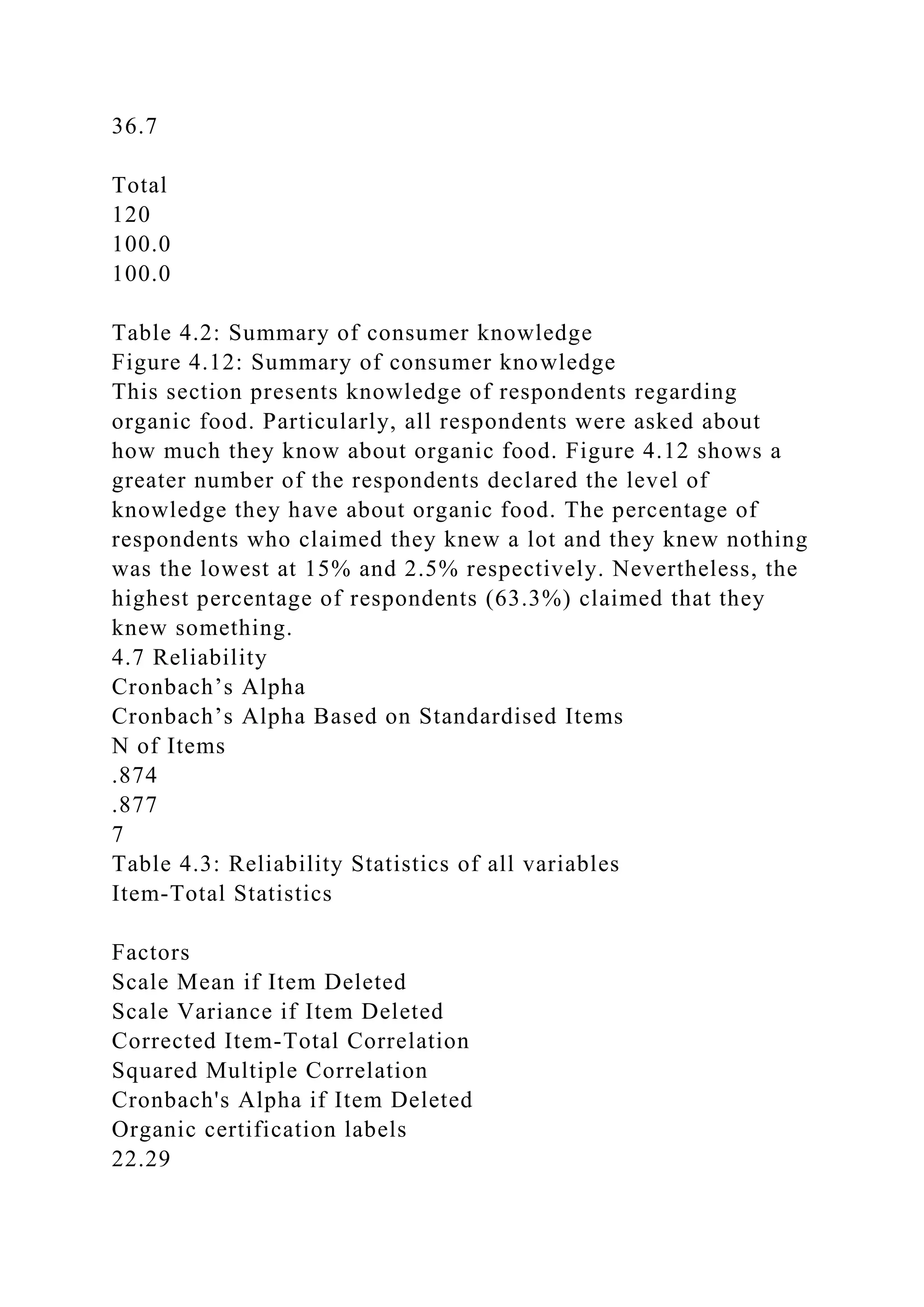

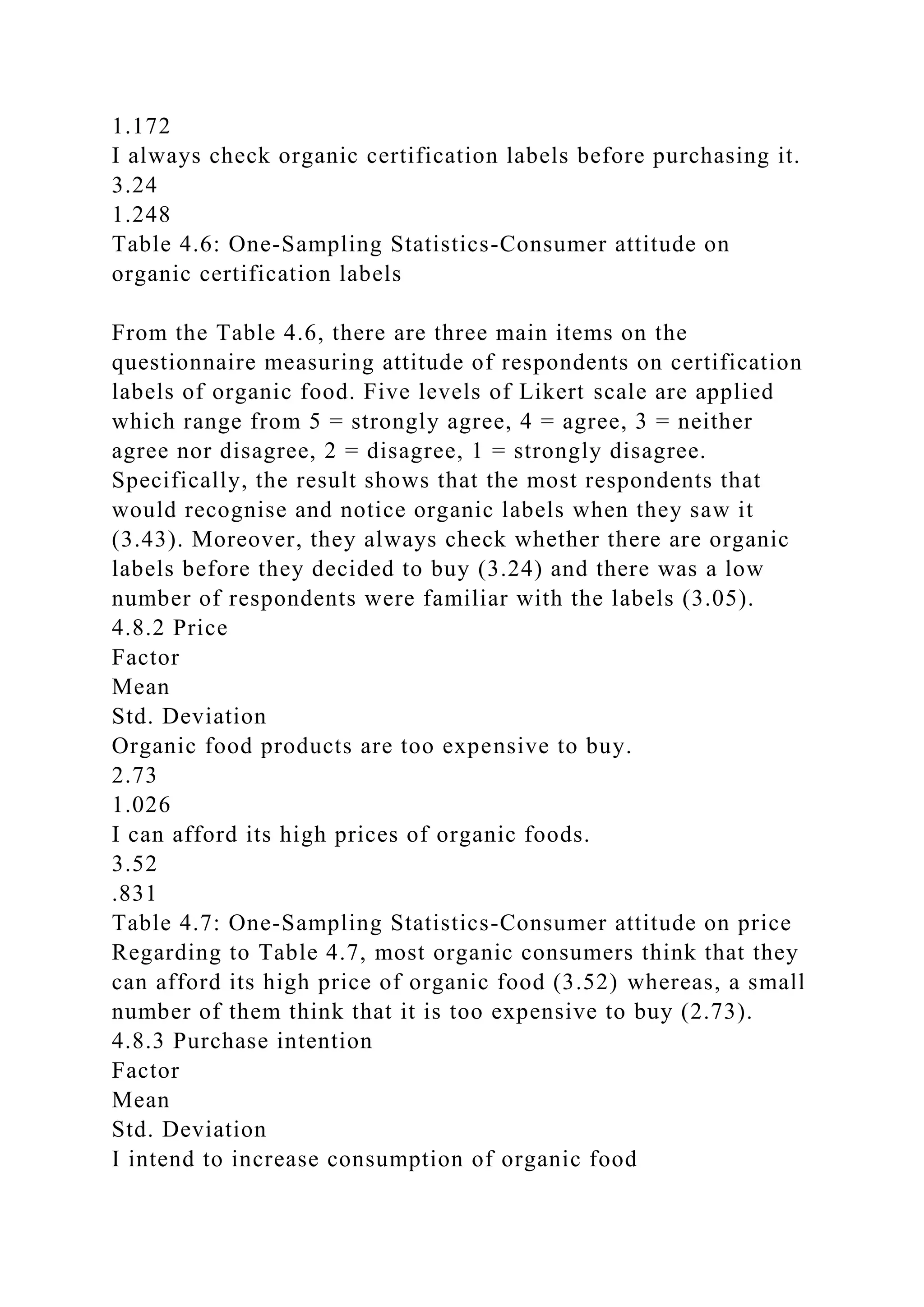

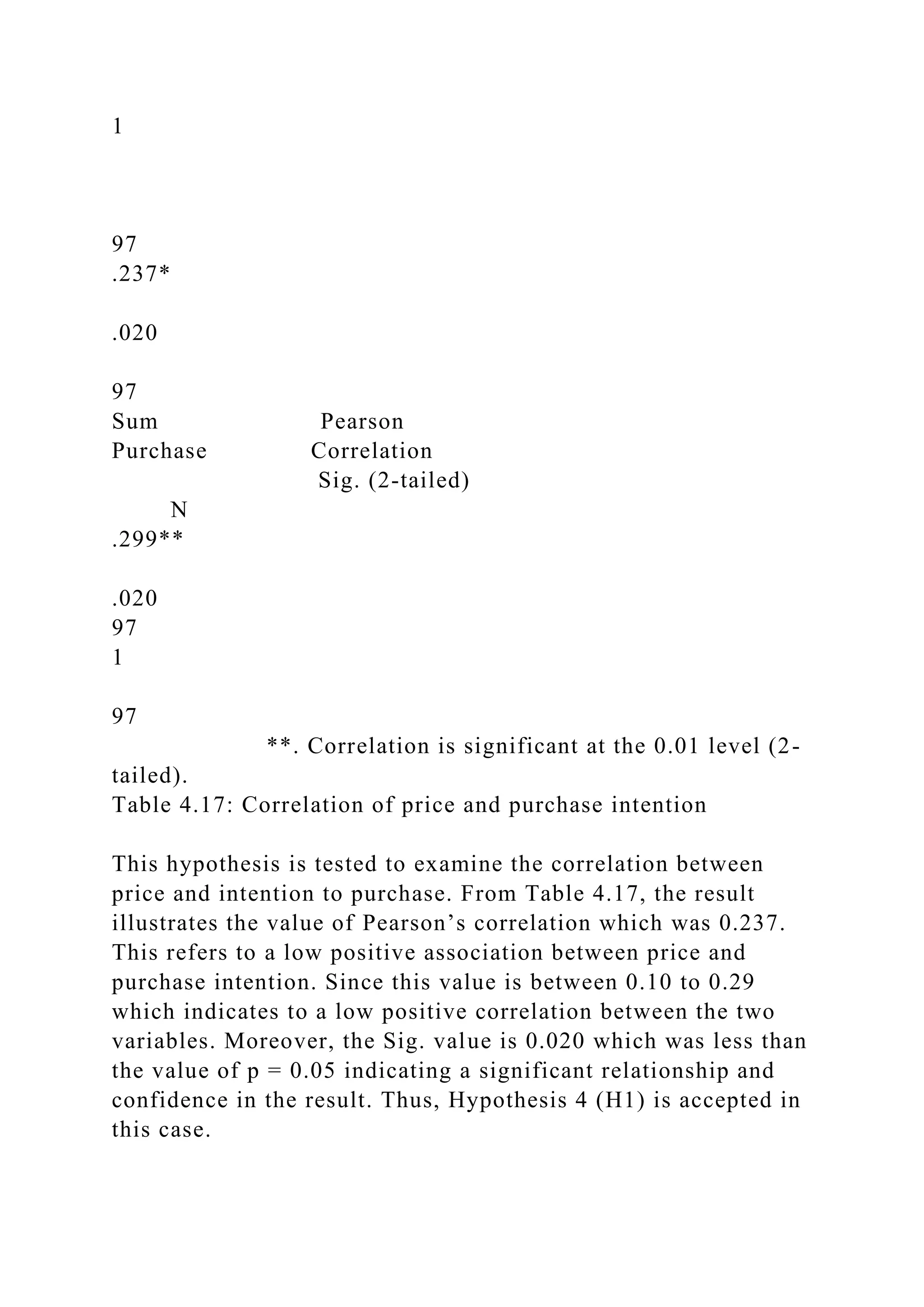

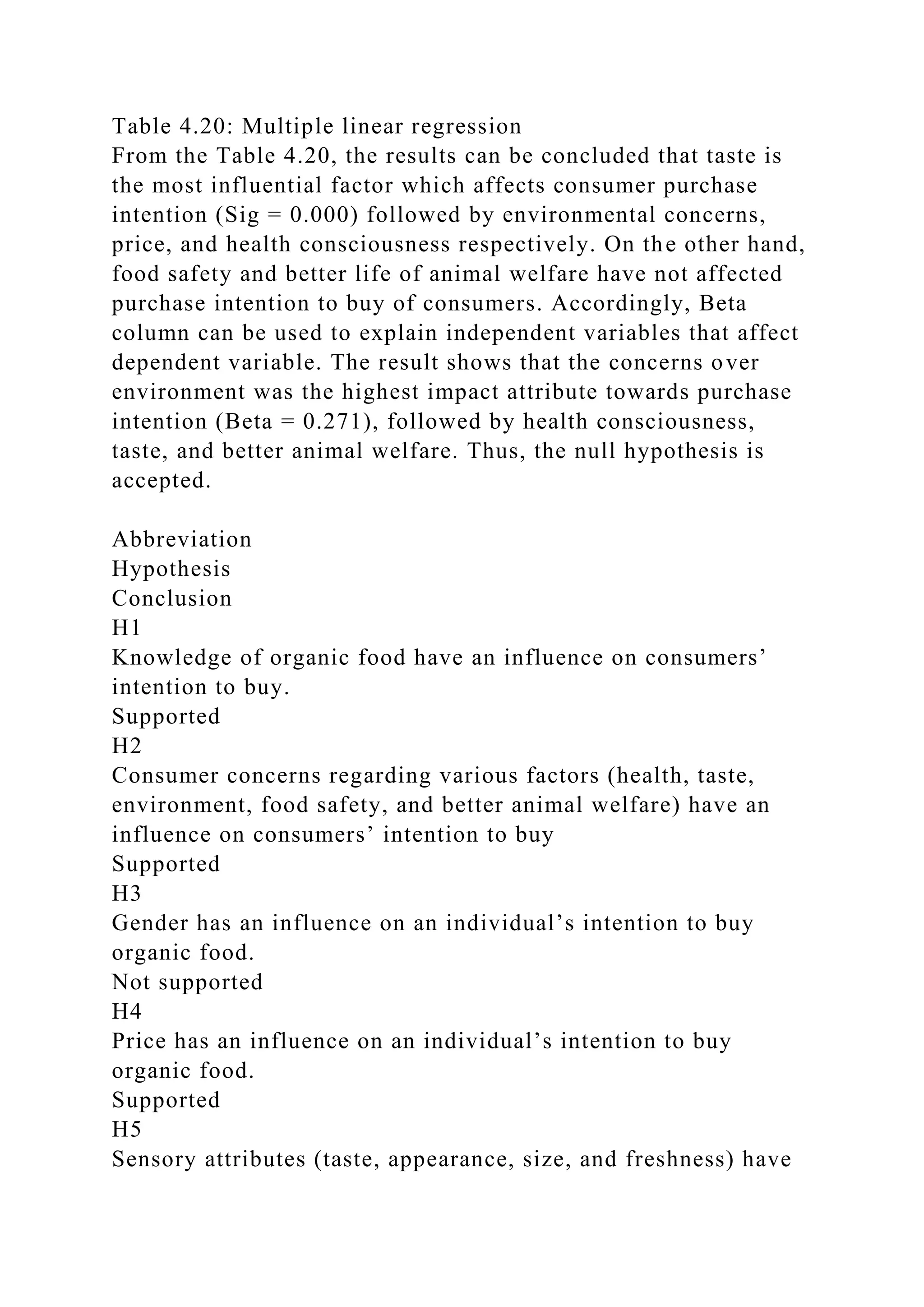

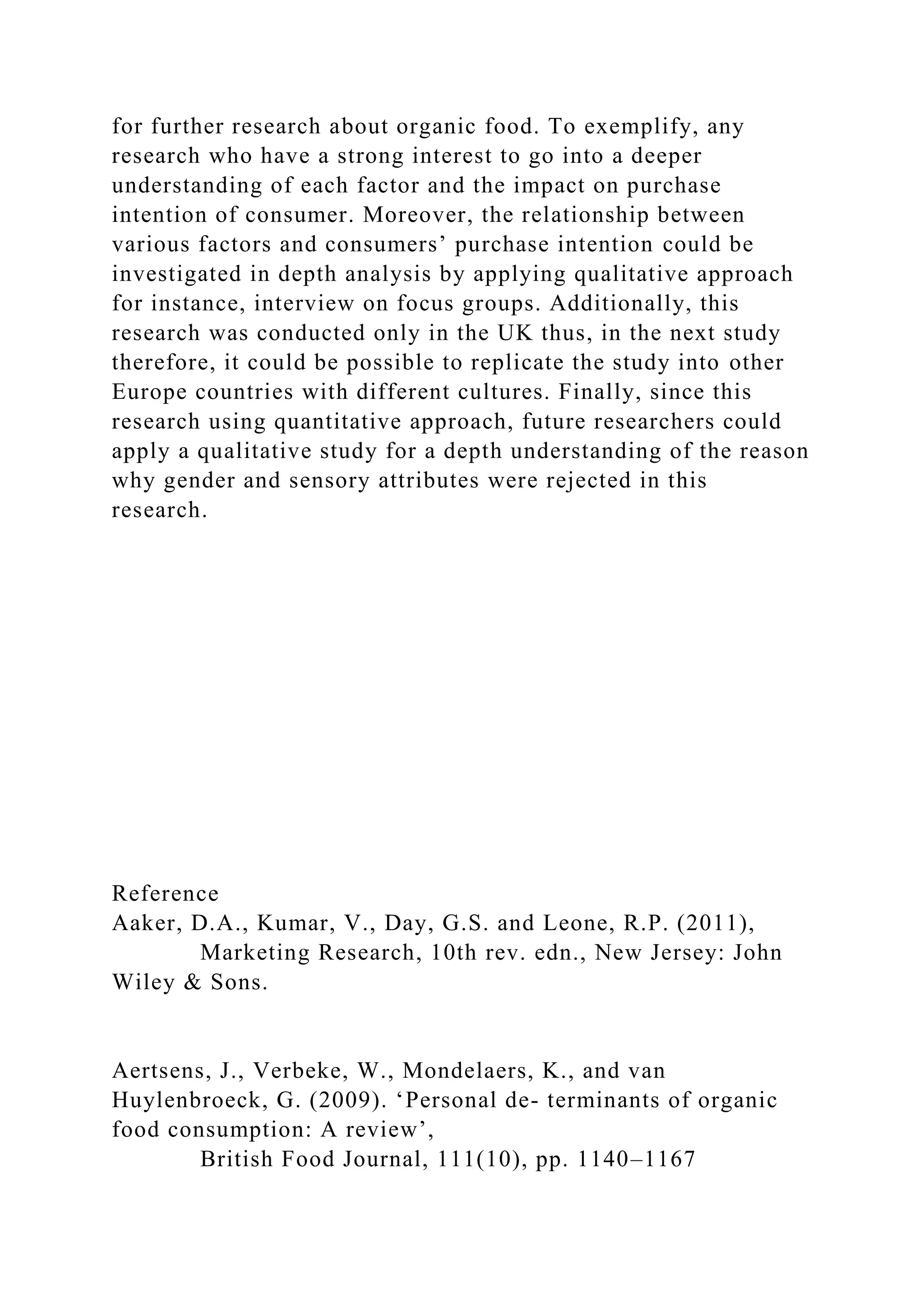

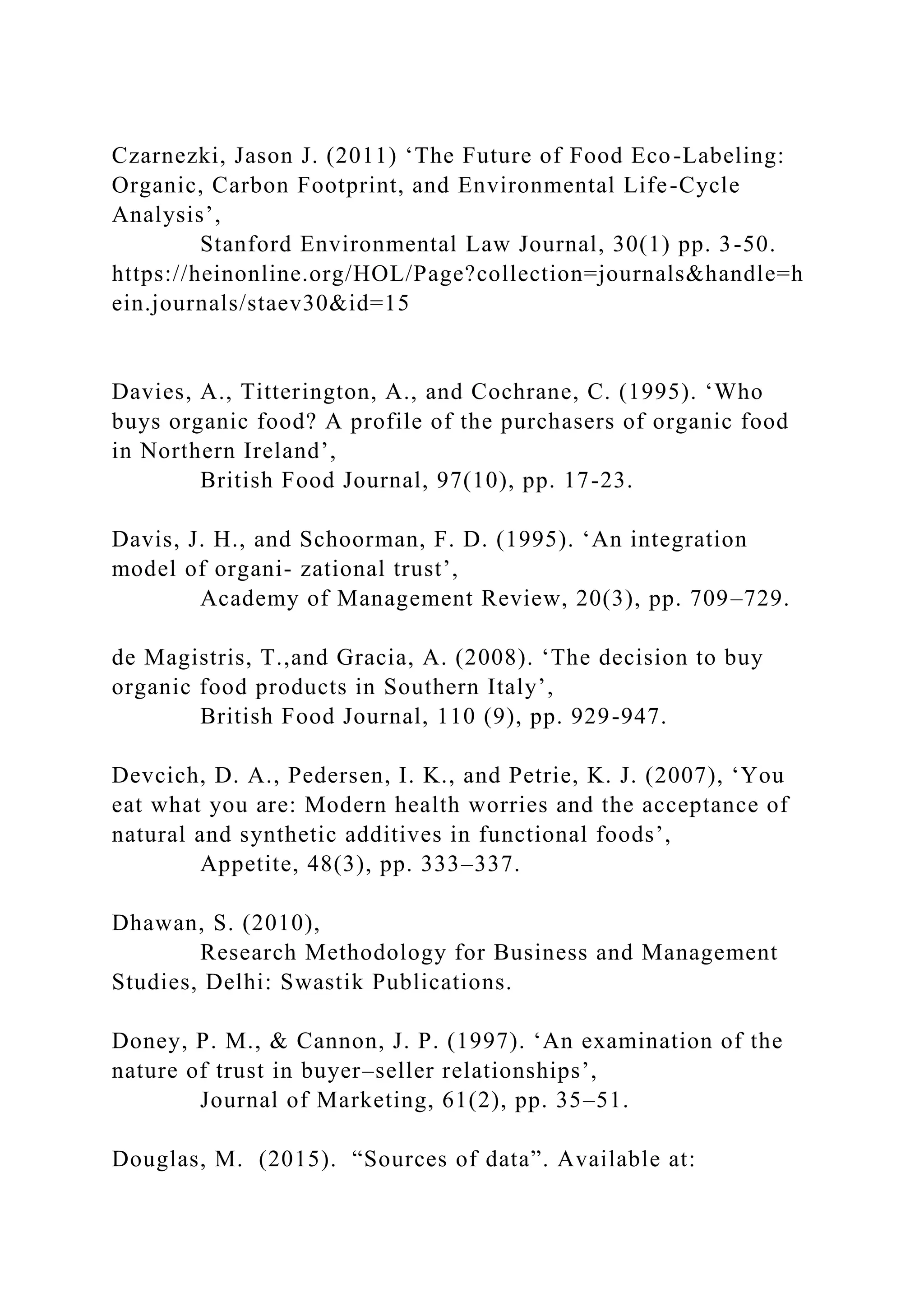

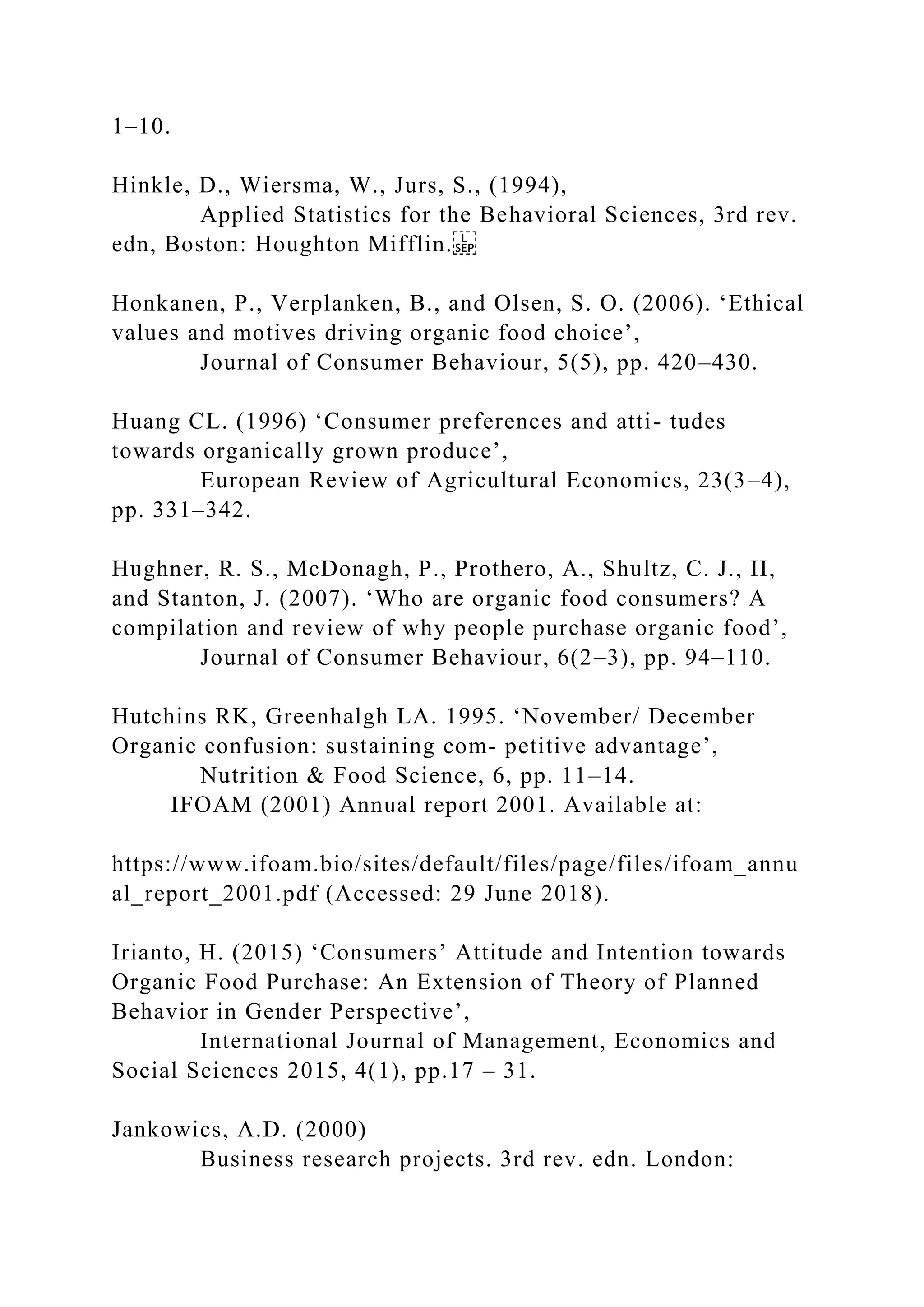

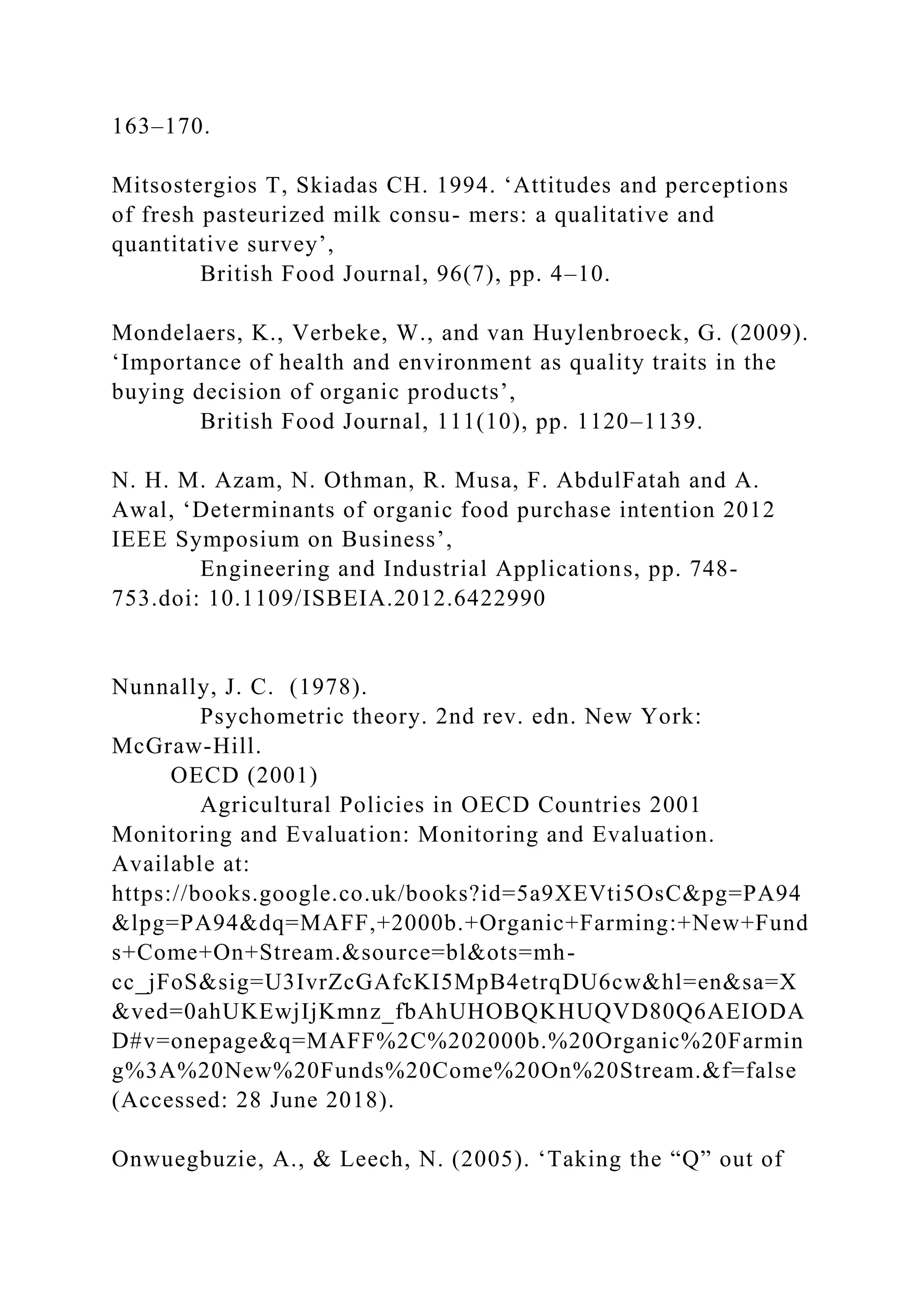

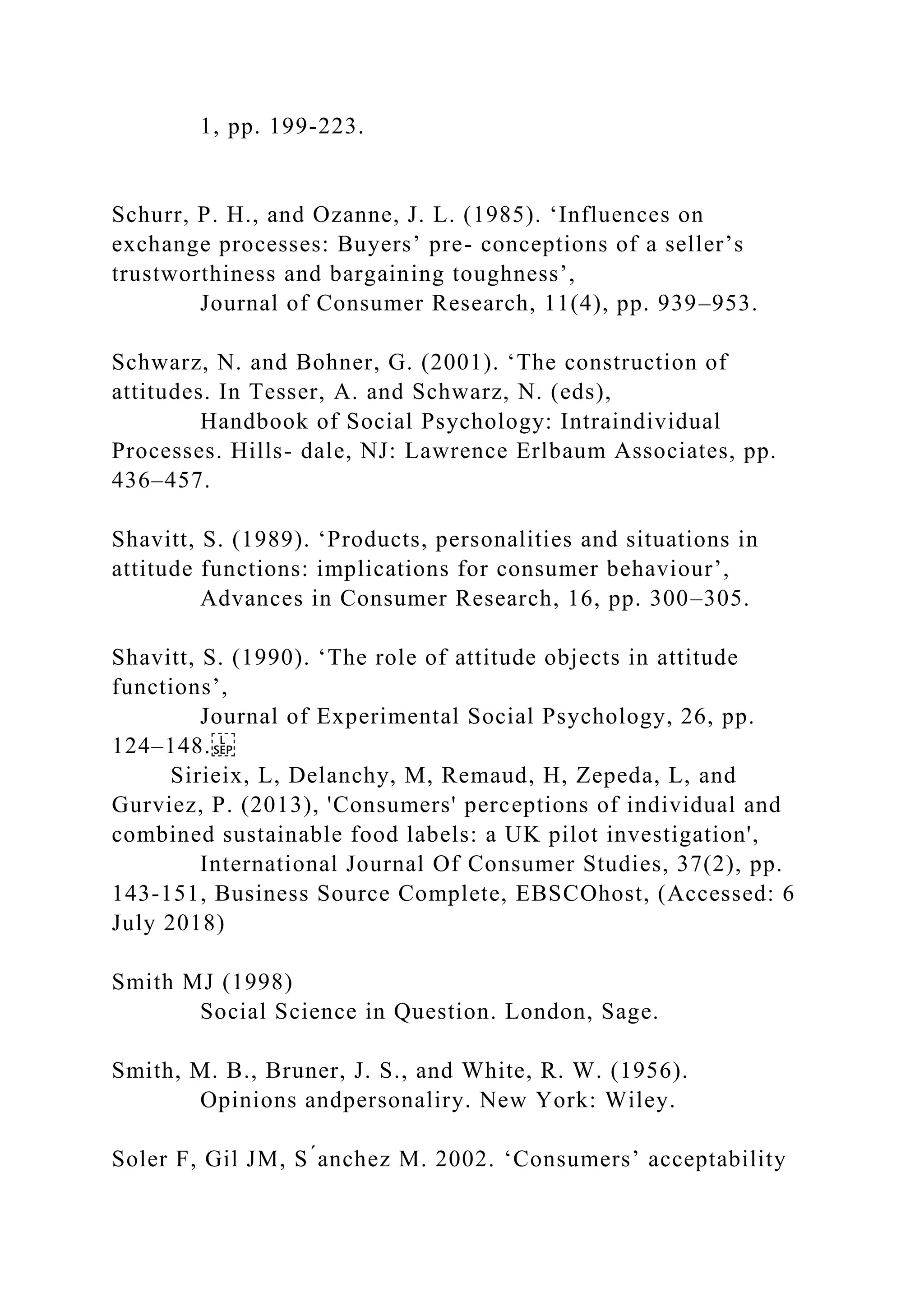

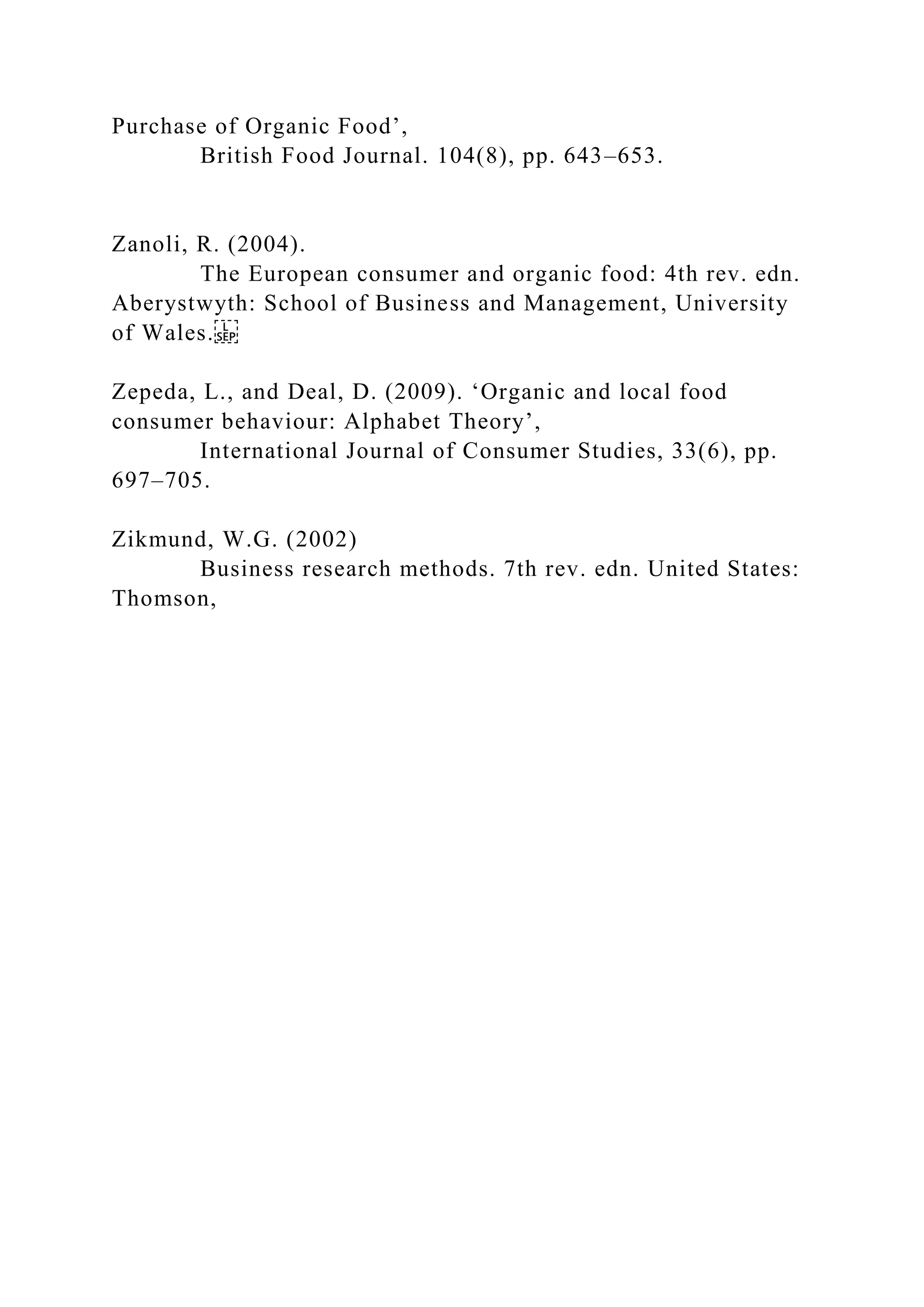

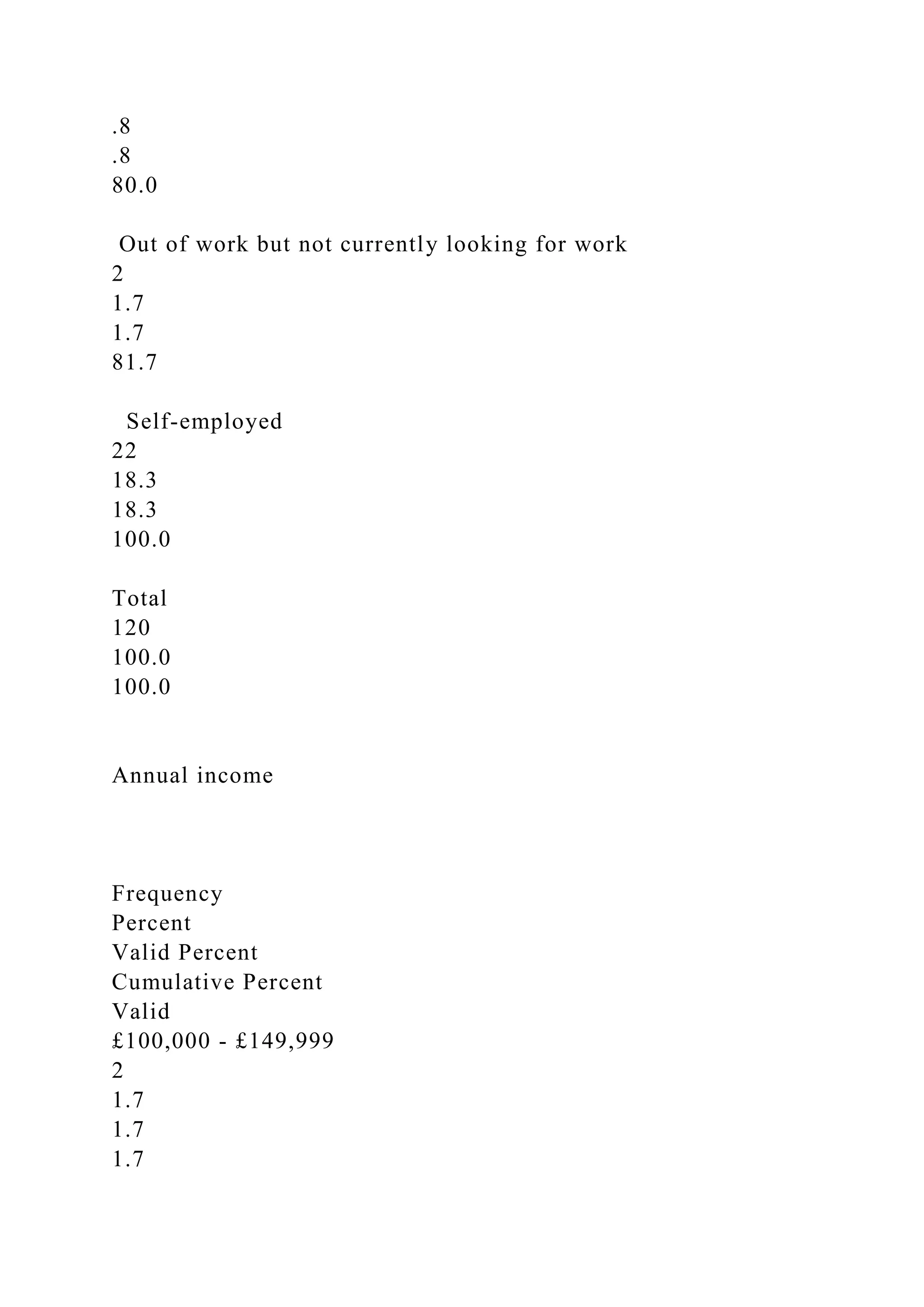

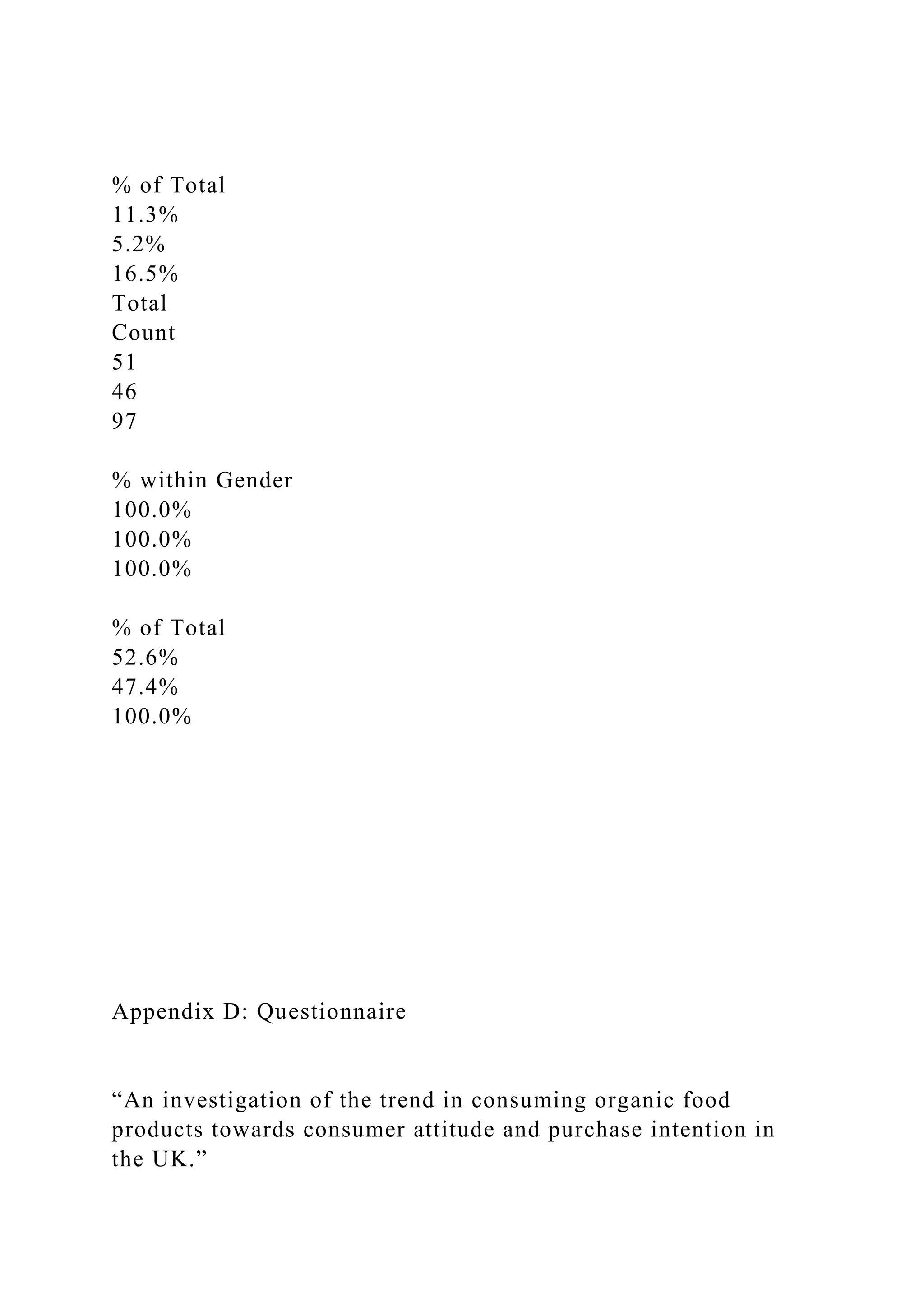

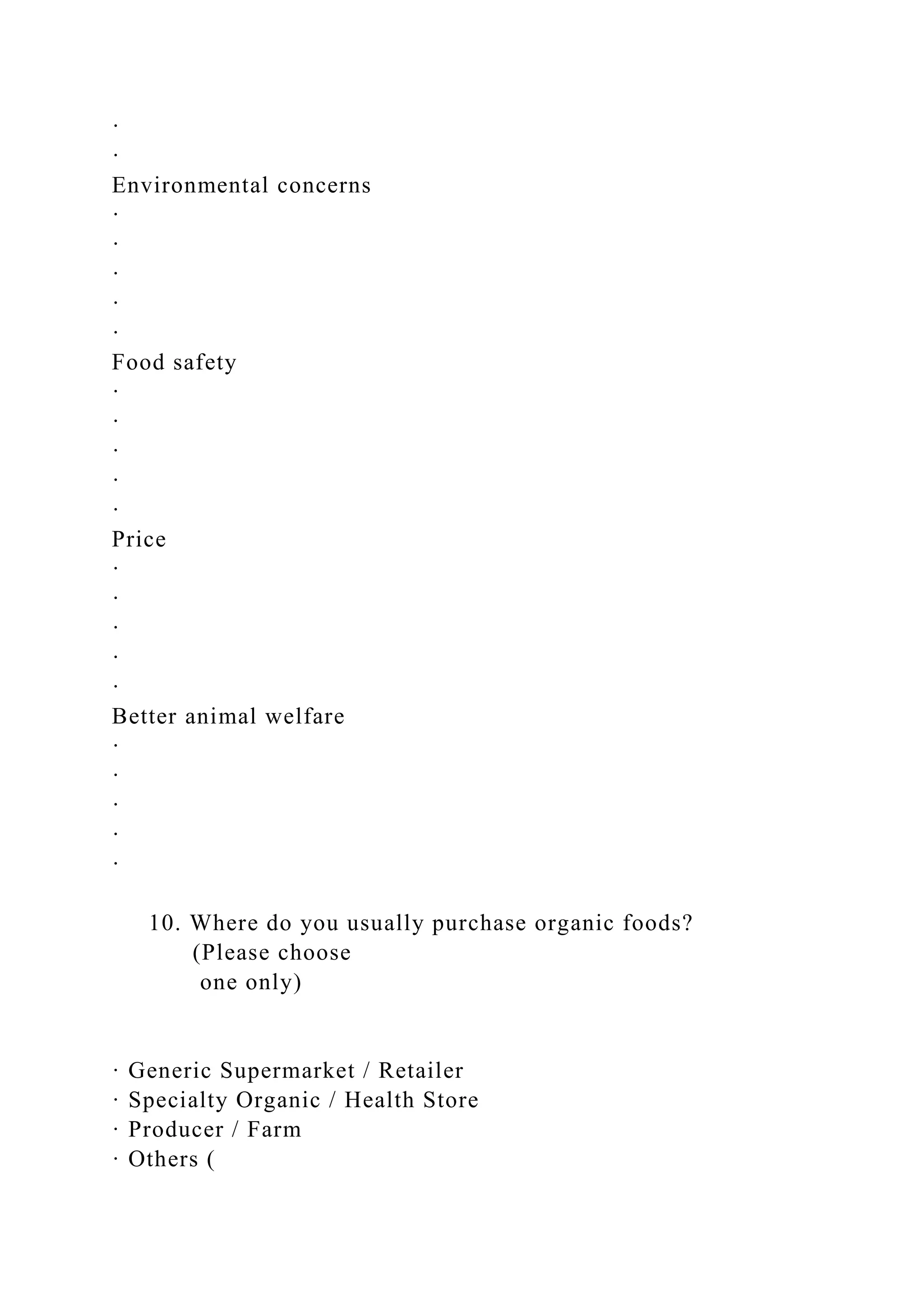

![may imply that the higher products have the organic

certification labels, the stronger determinant of purchase

intention. As a result of this, the Hypothesis 5 (H1) is accepted.

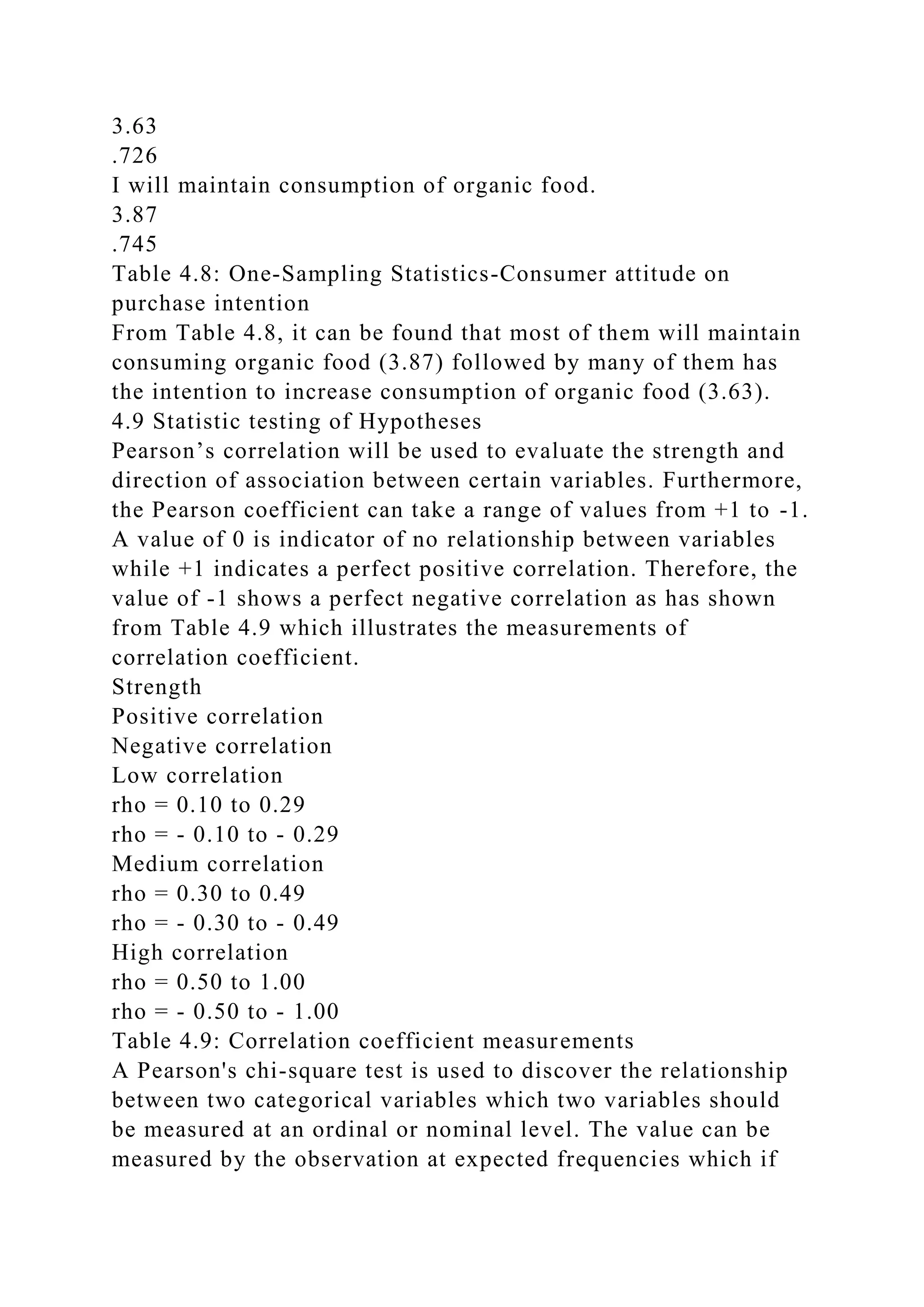

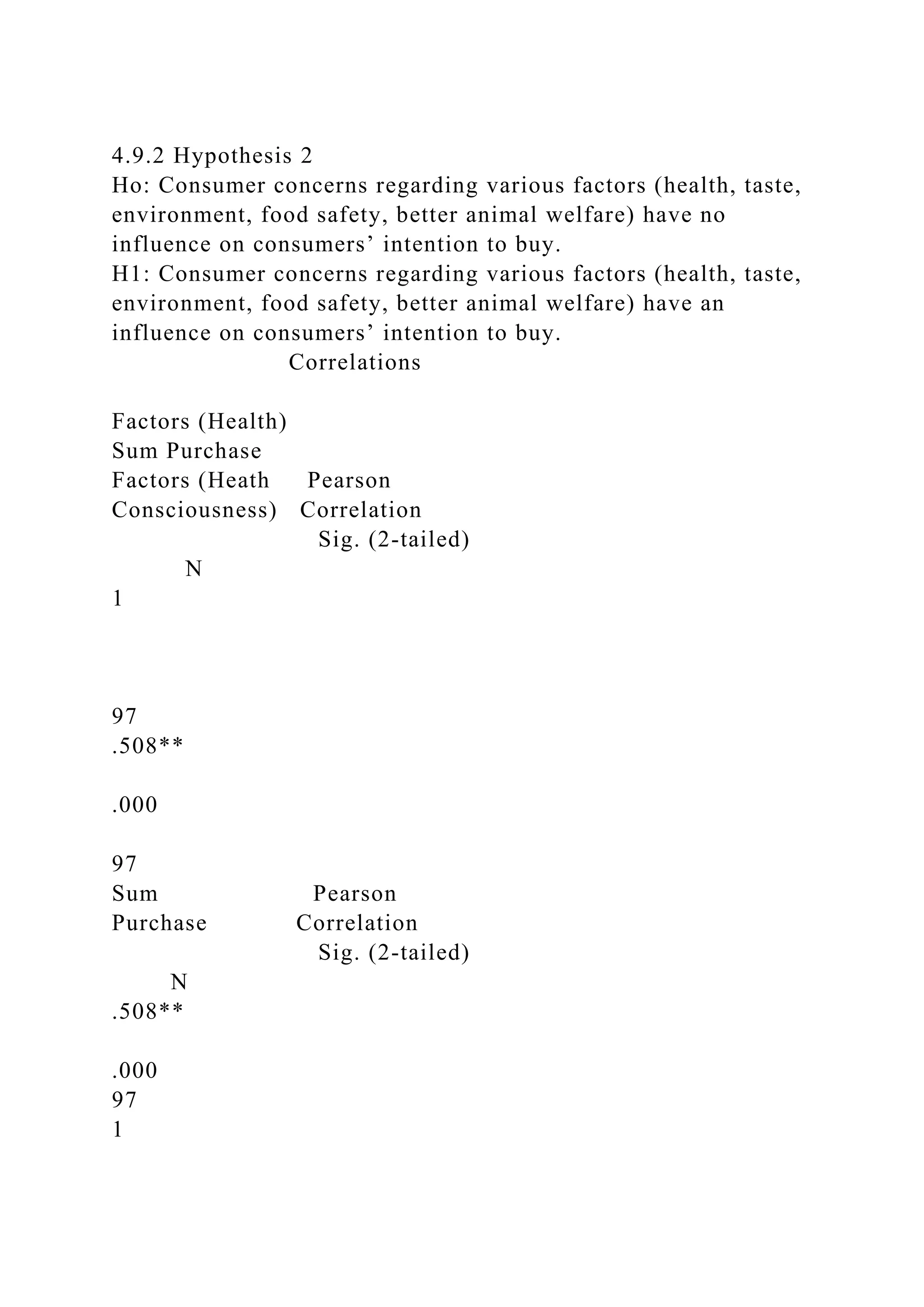

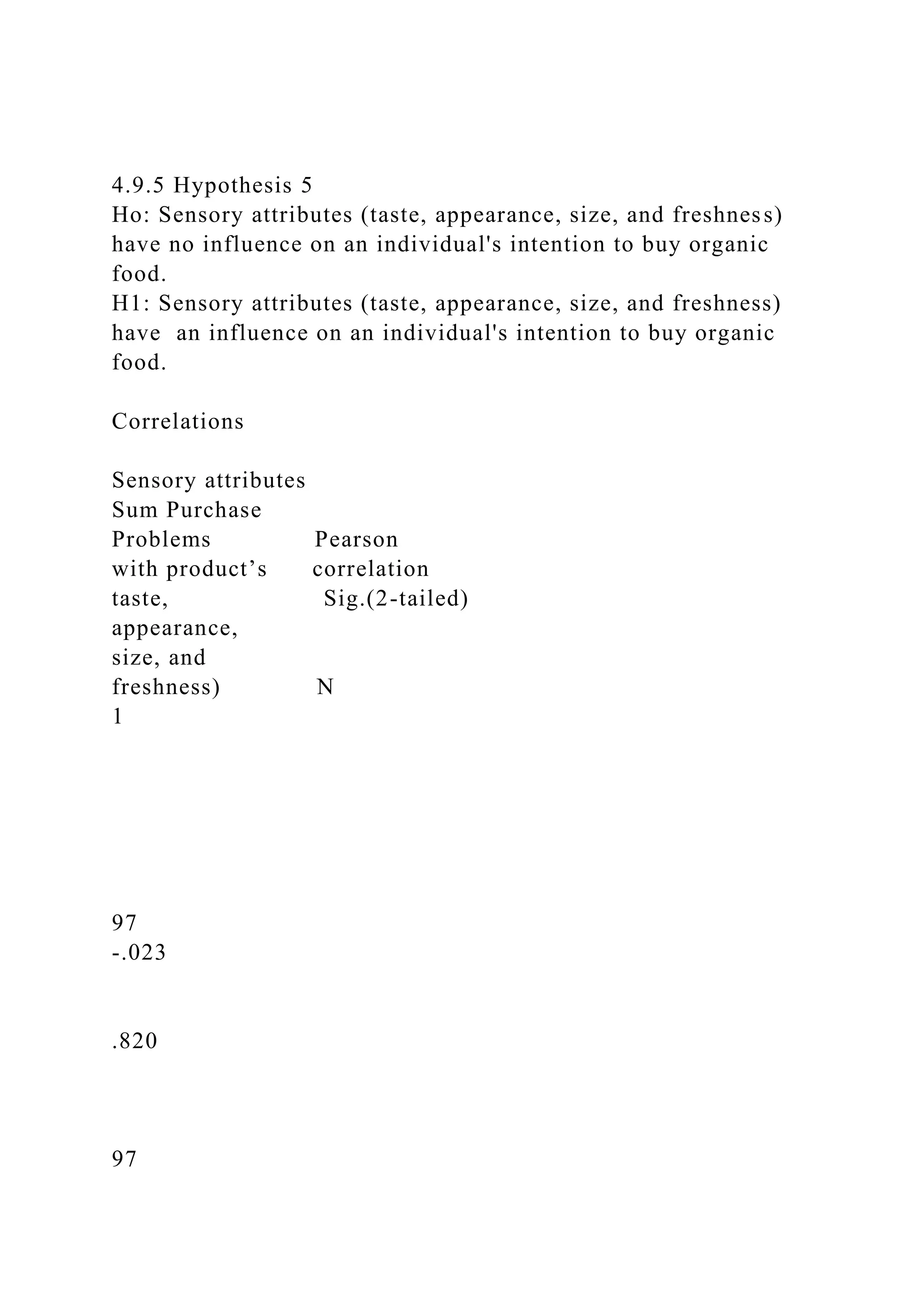

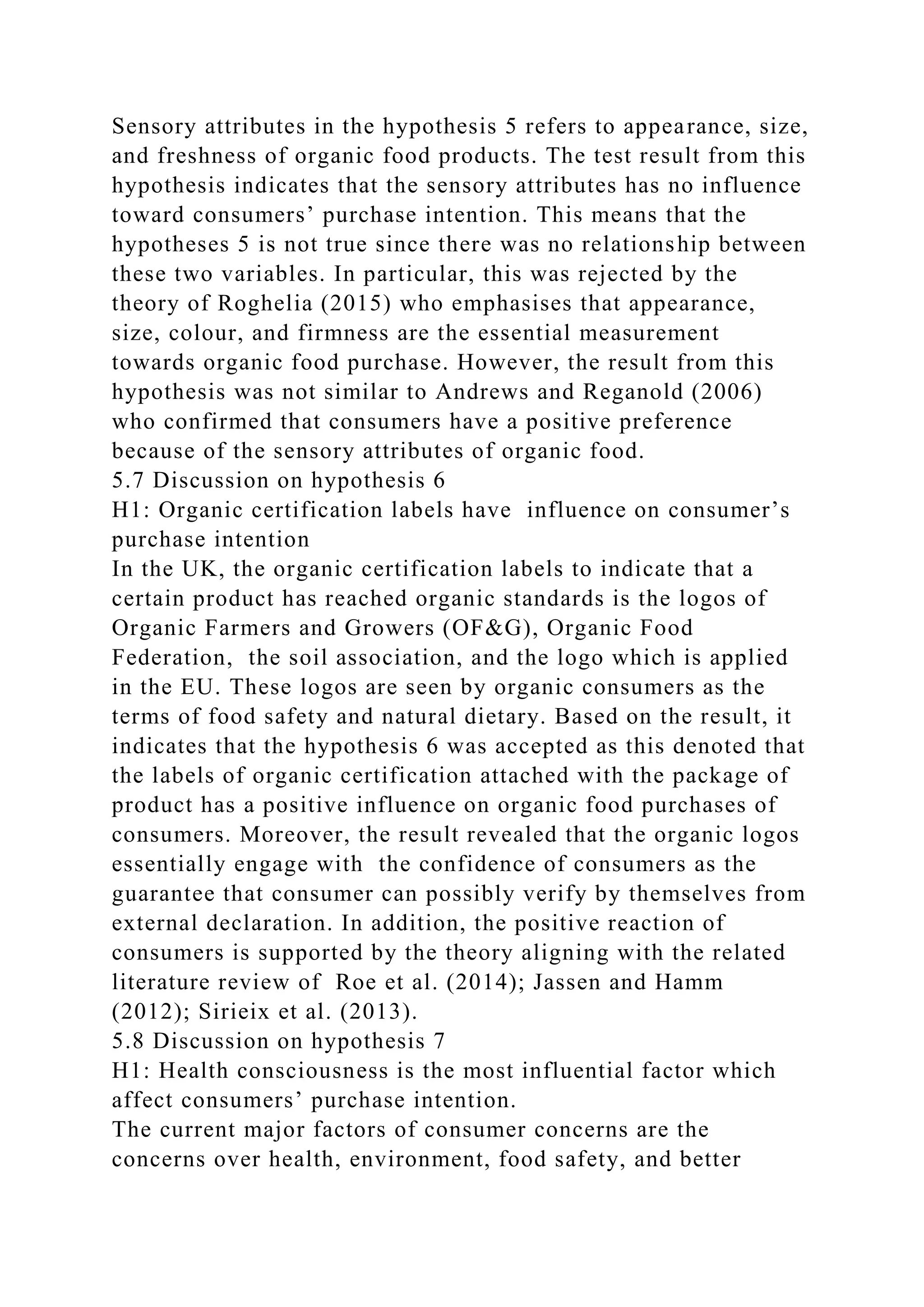

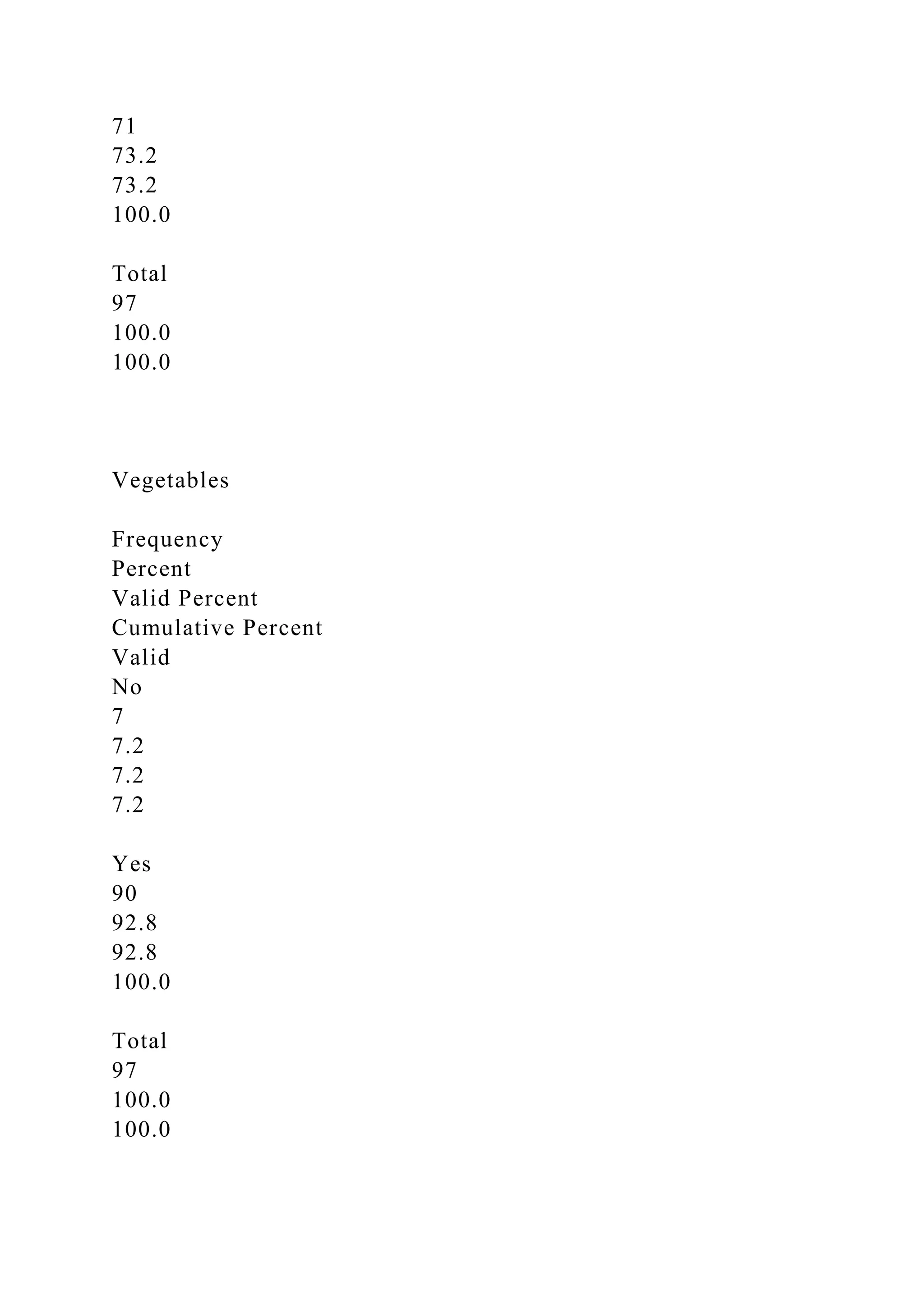

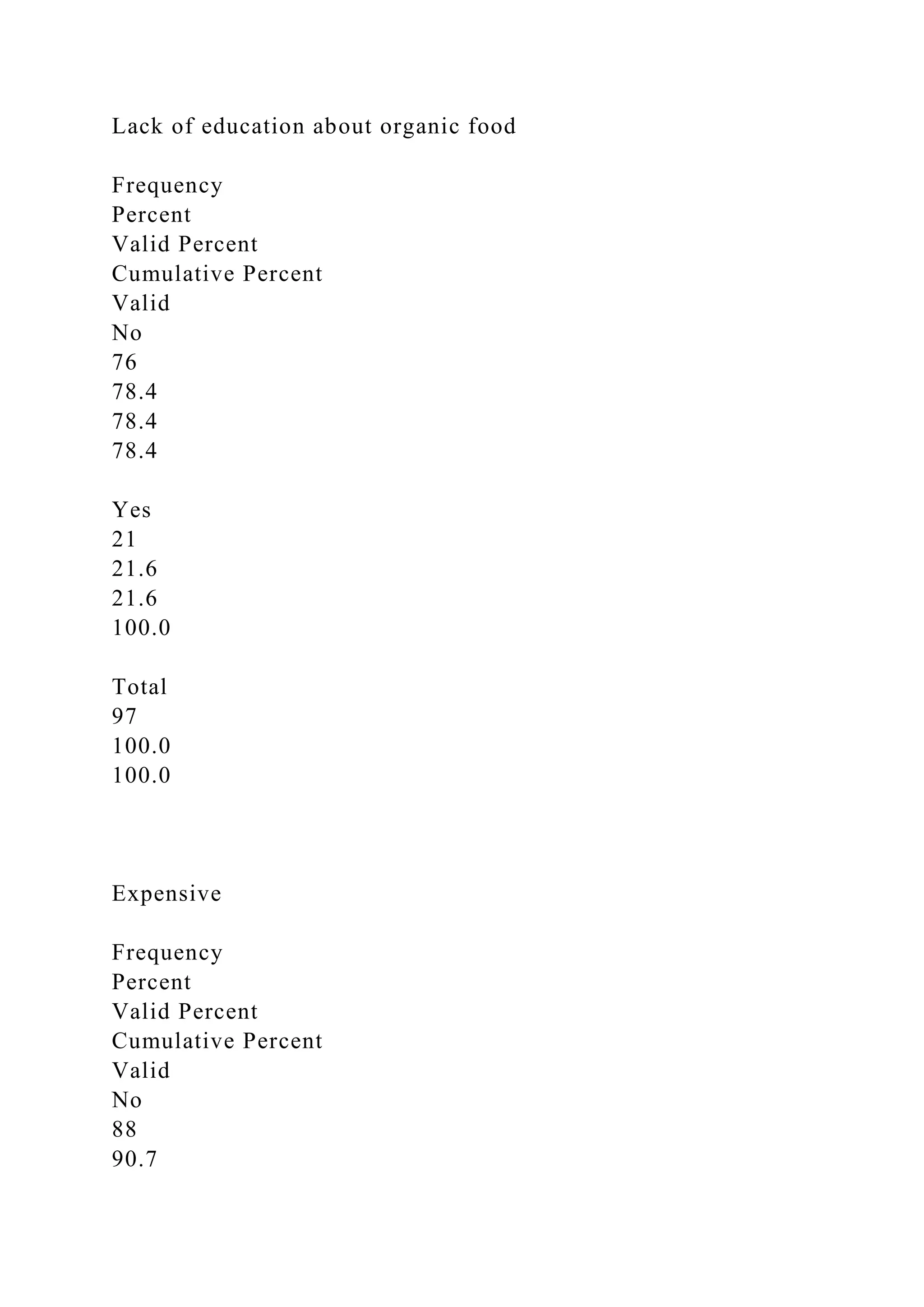

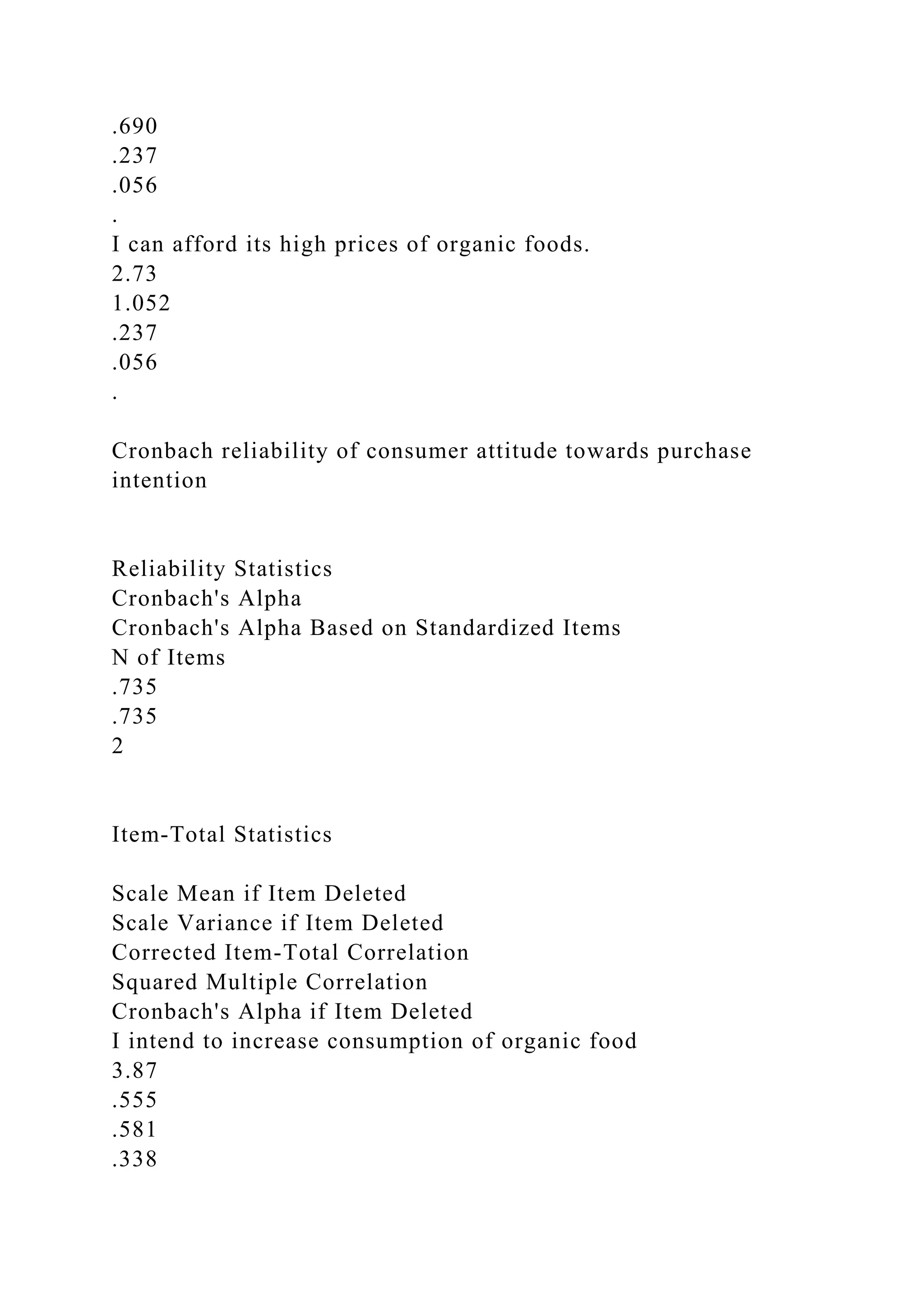

4.9.7 Hypothesis 7

Ho: Health consciousness is not the most influential factor

which affect consumer purchase intention.

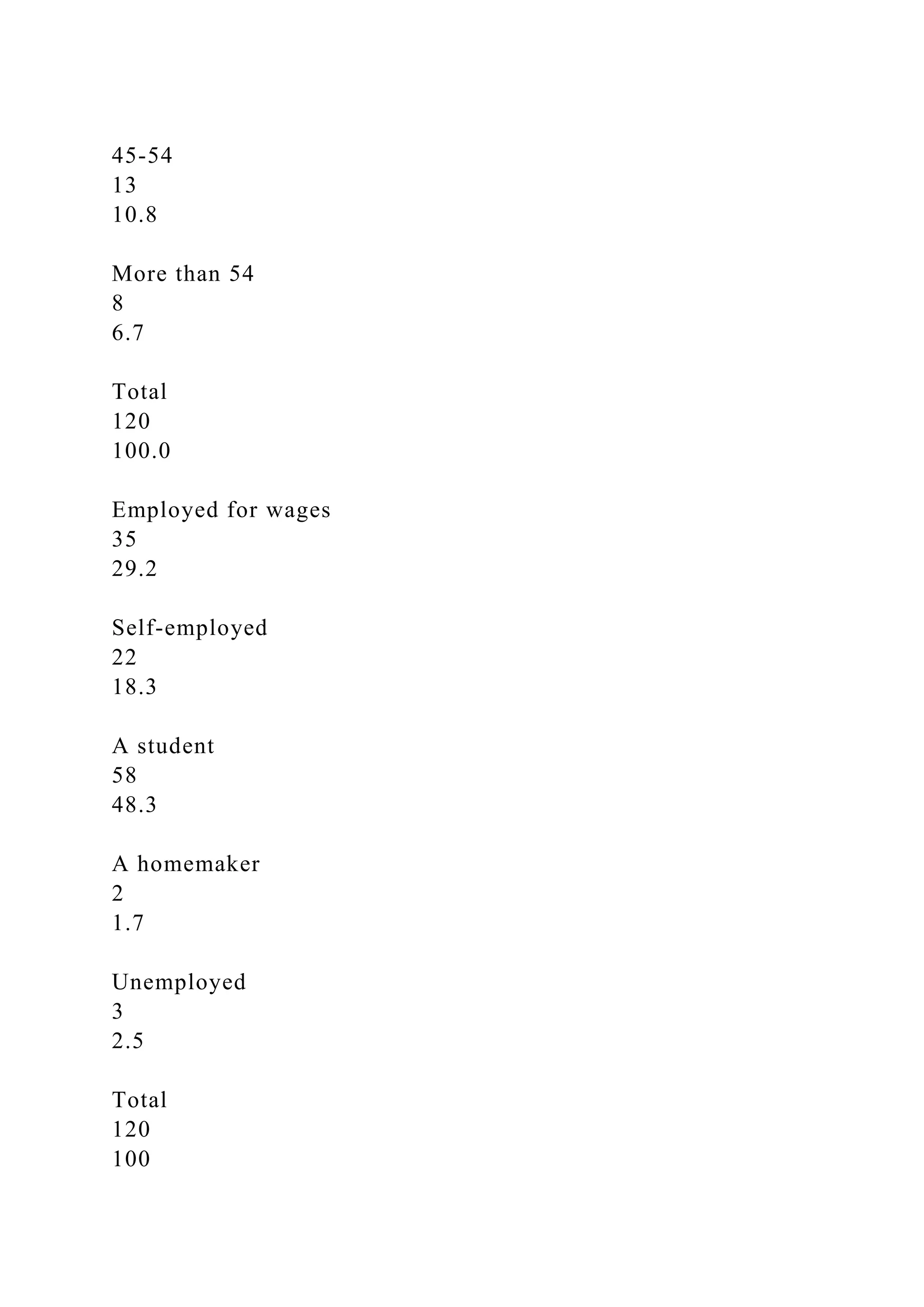

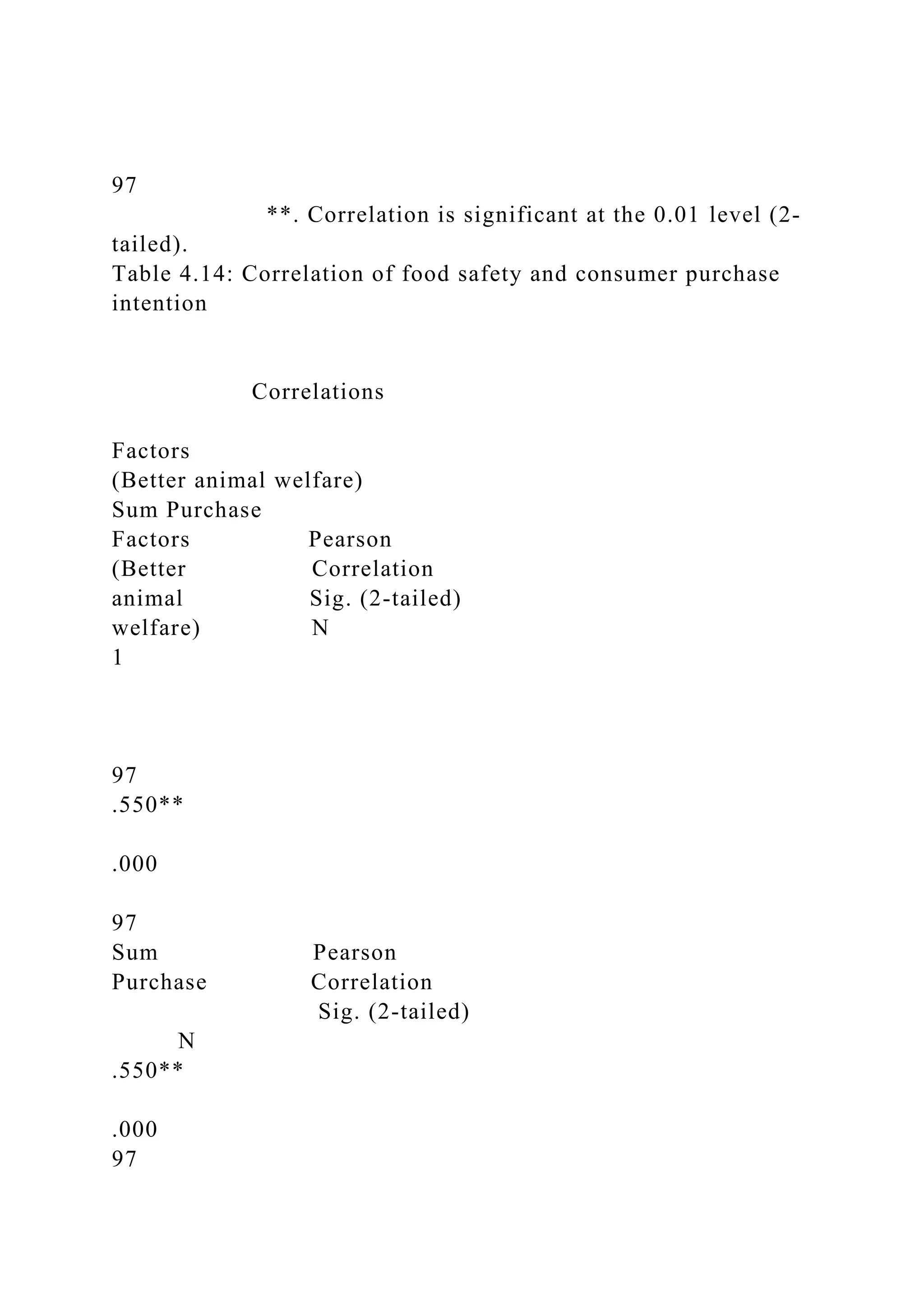

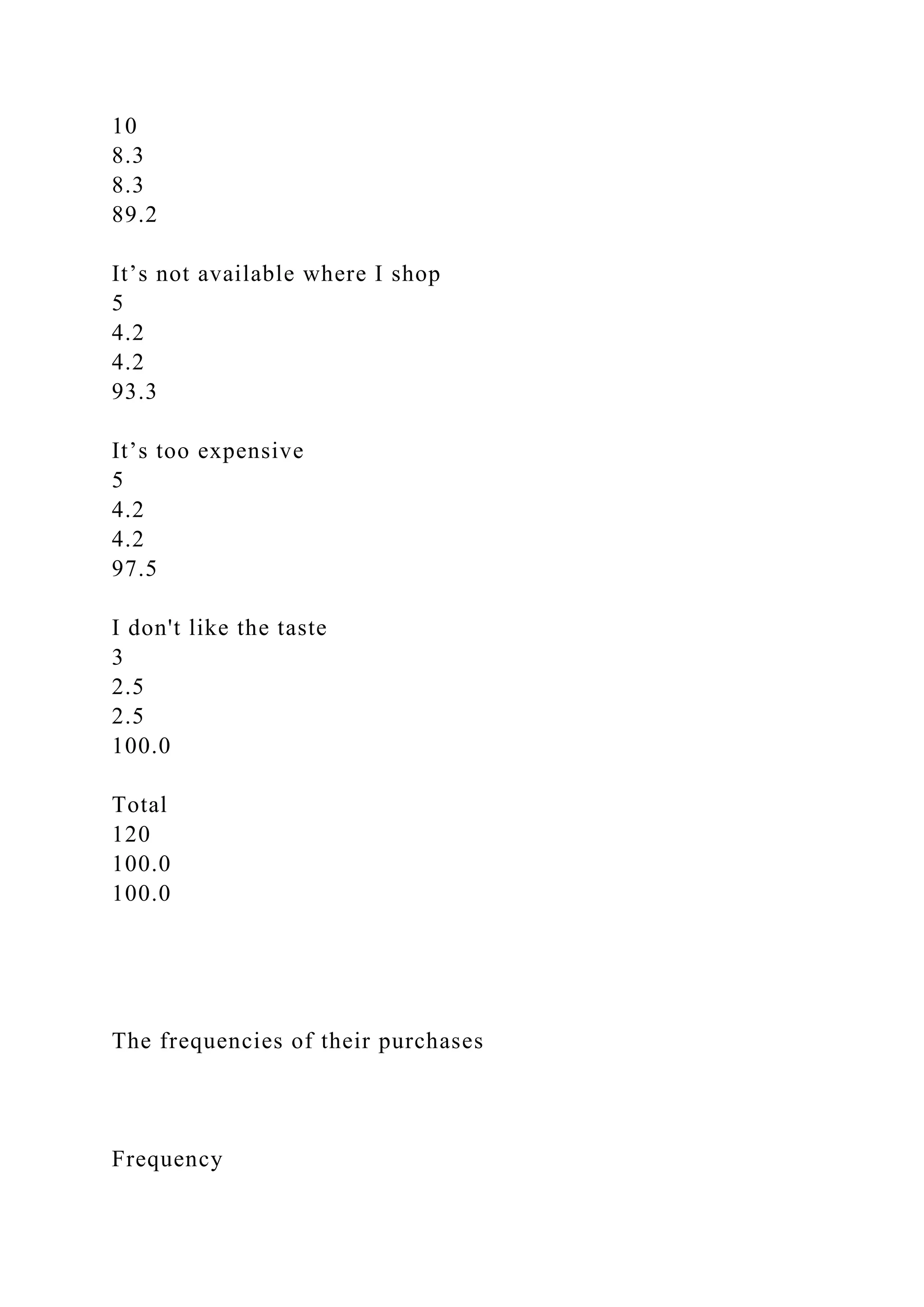

Model

Unstandardized Coefficients

Standardized Coefficients

Model

Unstandardized Coefficients

t

Sig.

1

(Constant)

2.246

.245

9.155

.000

Factors [Health

consciousness]

.156

.084

.250

1.855

.067

Factors [Taste]

.126

.059](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/submittedinpartfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof-230119024927-31555ff9/75/Submitted-in-part-fulfilment-of-the-requirements-for-the-degree-of-docx-82-2048.jpg)

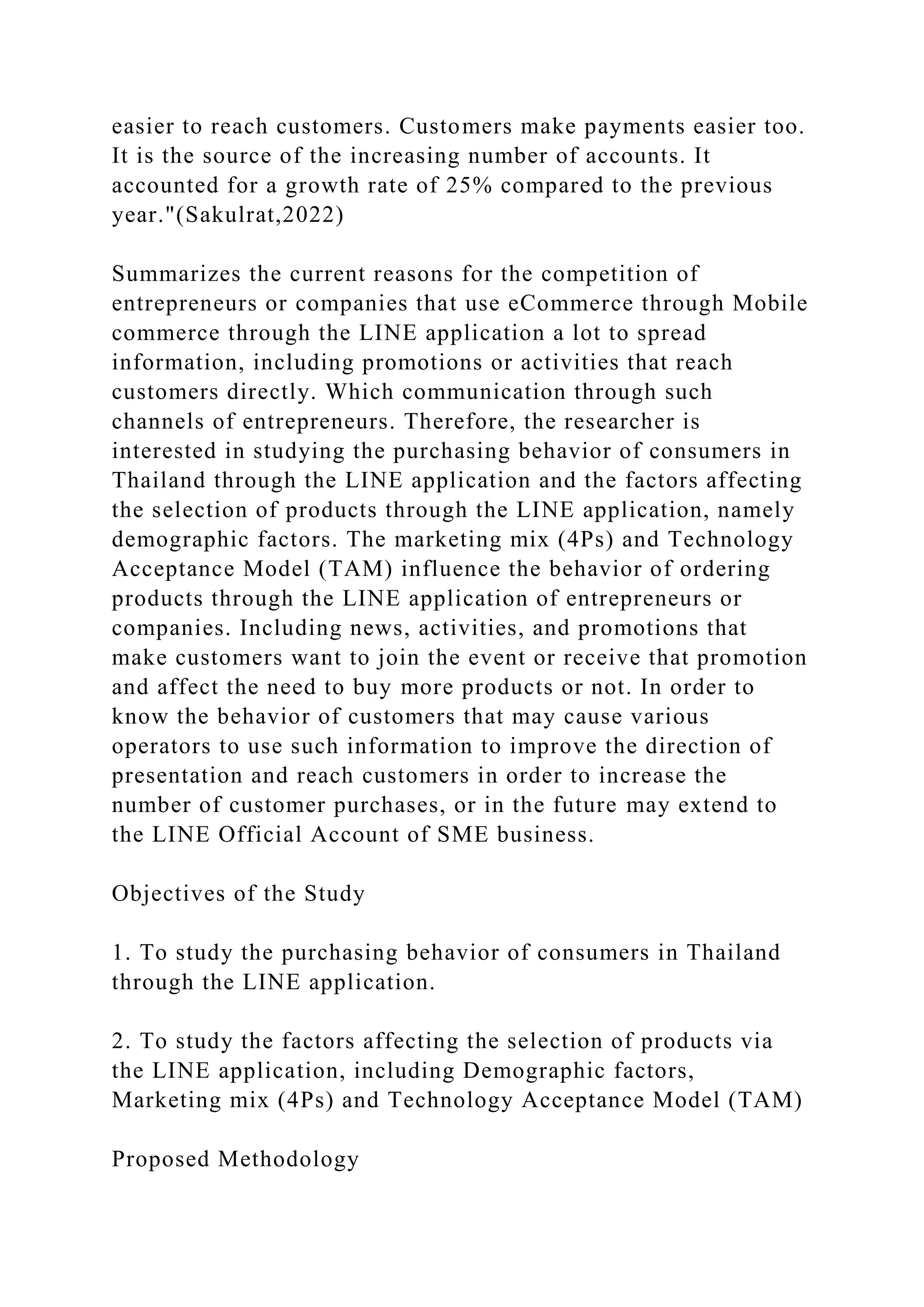

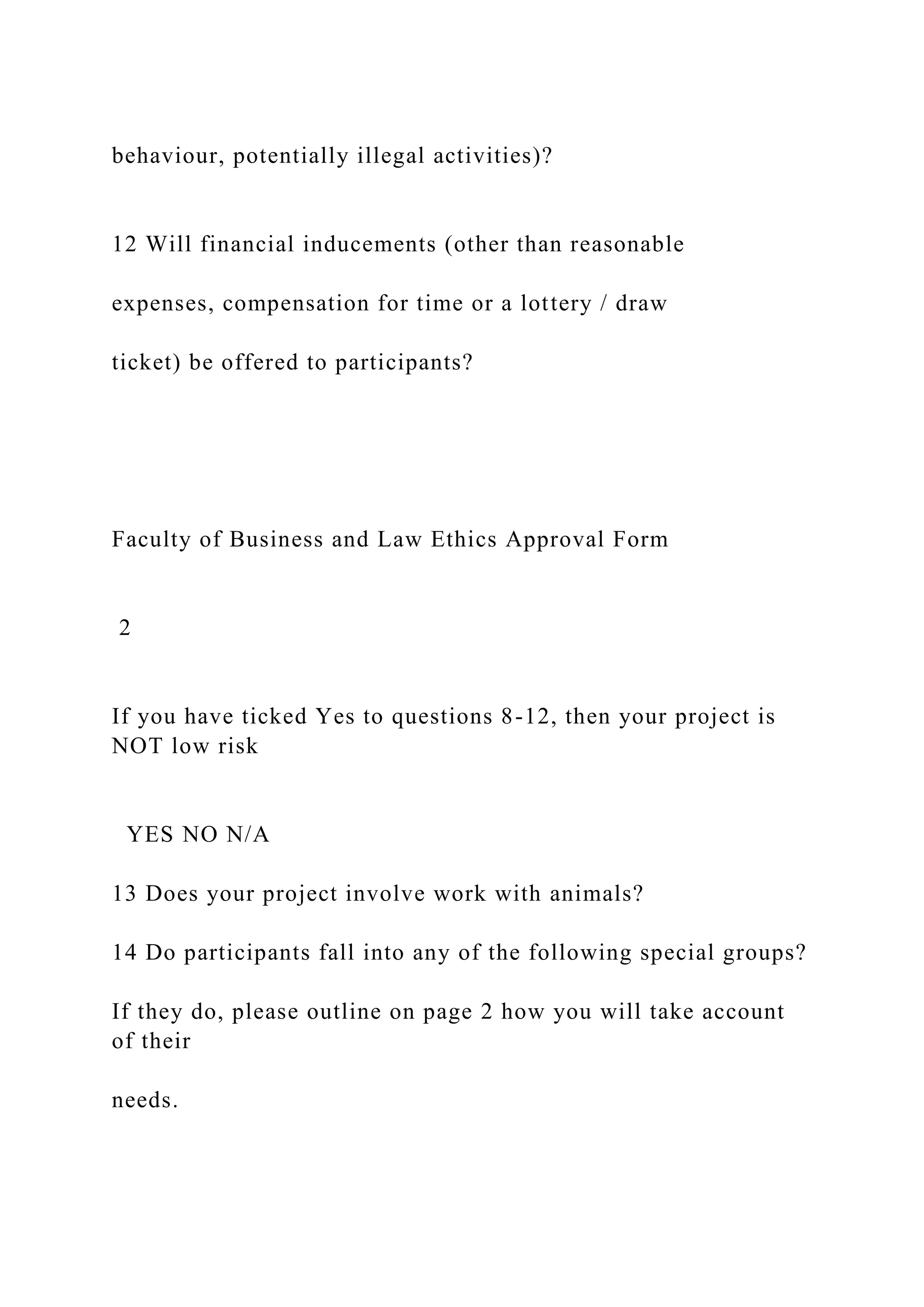

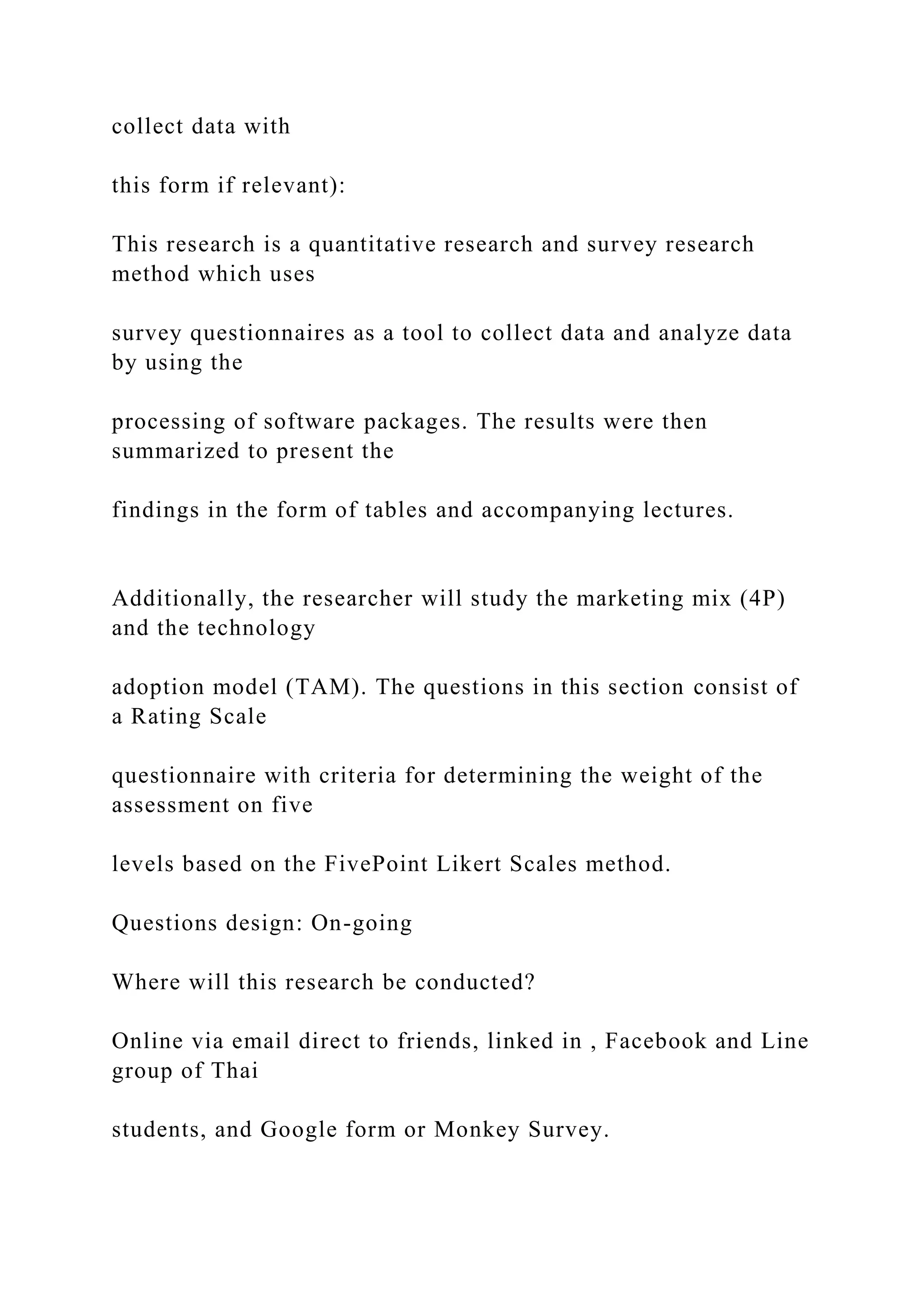

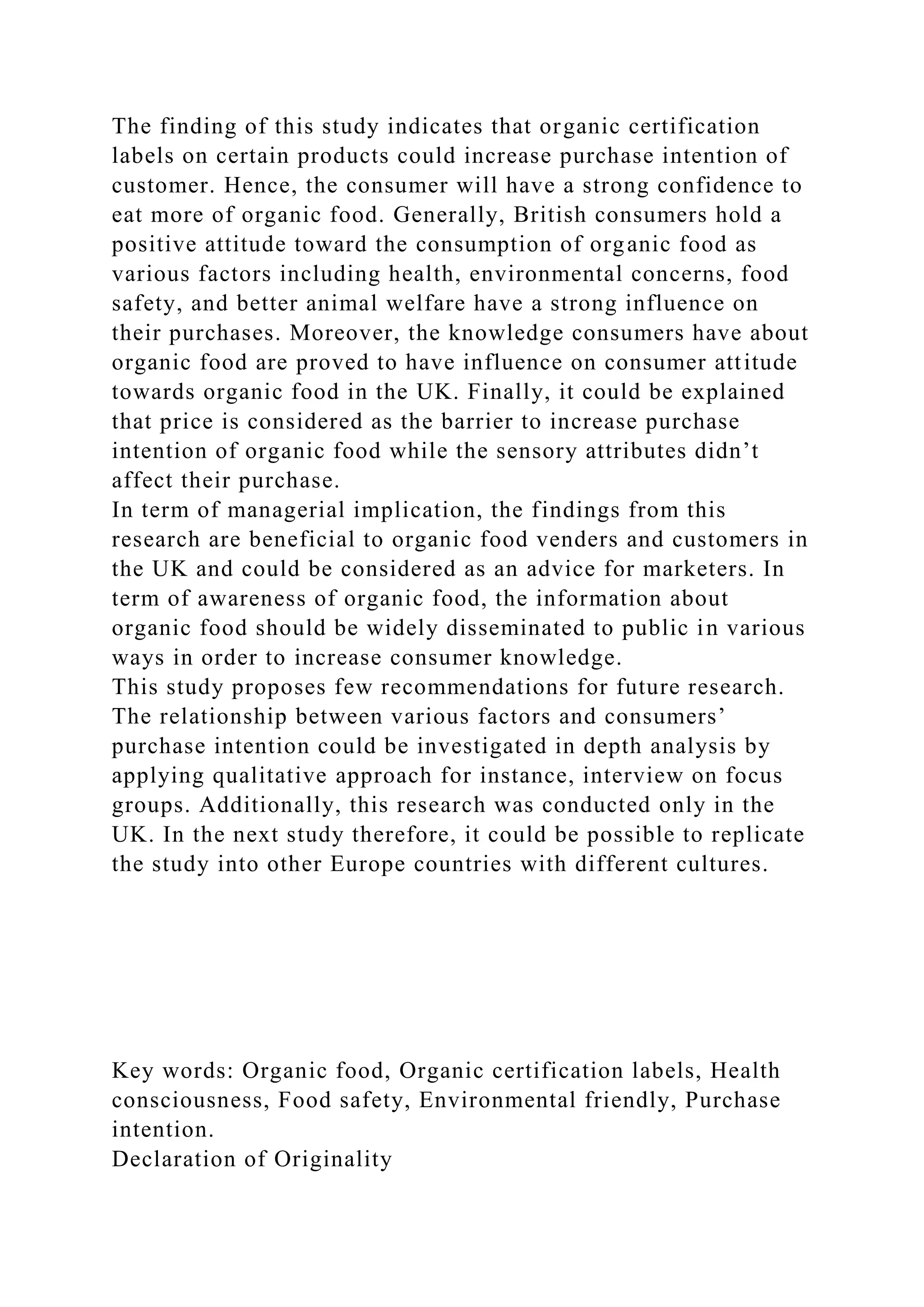

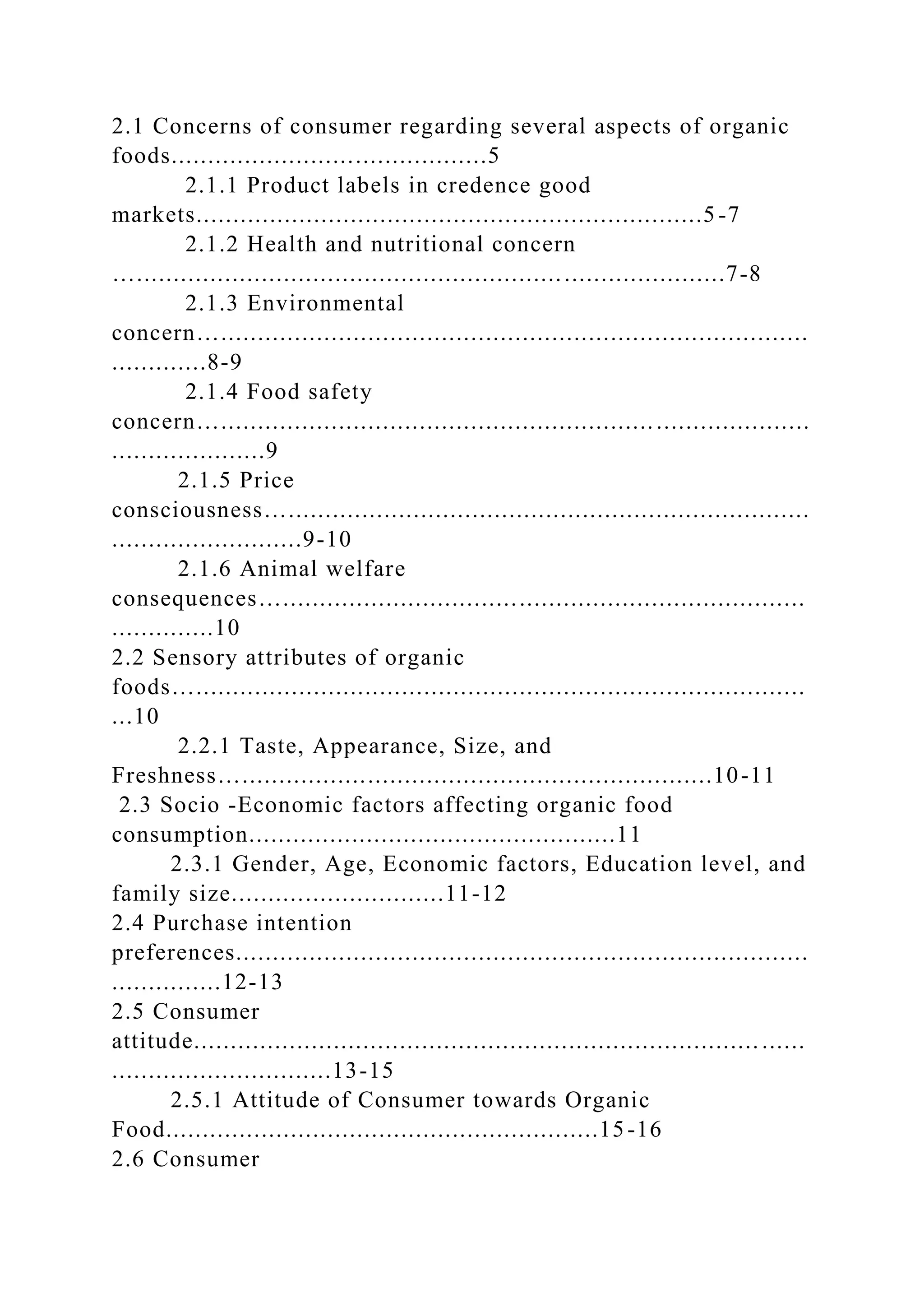

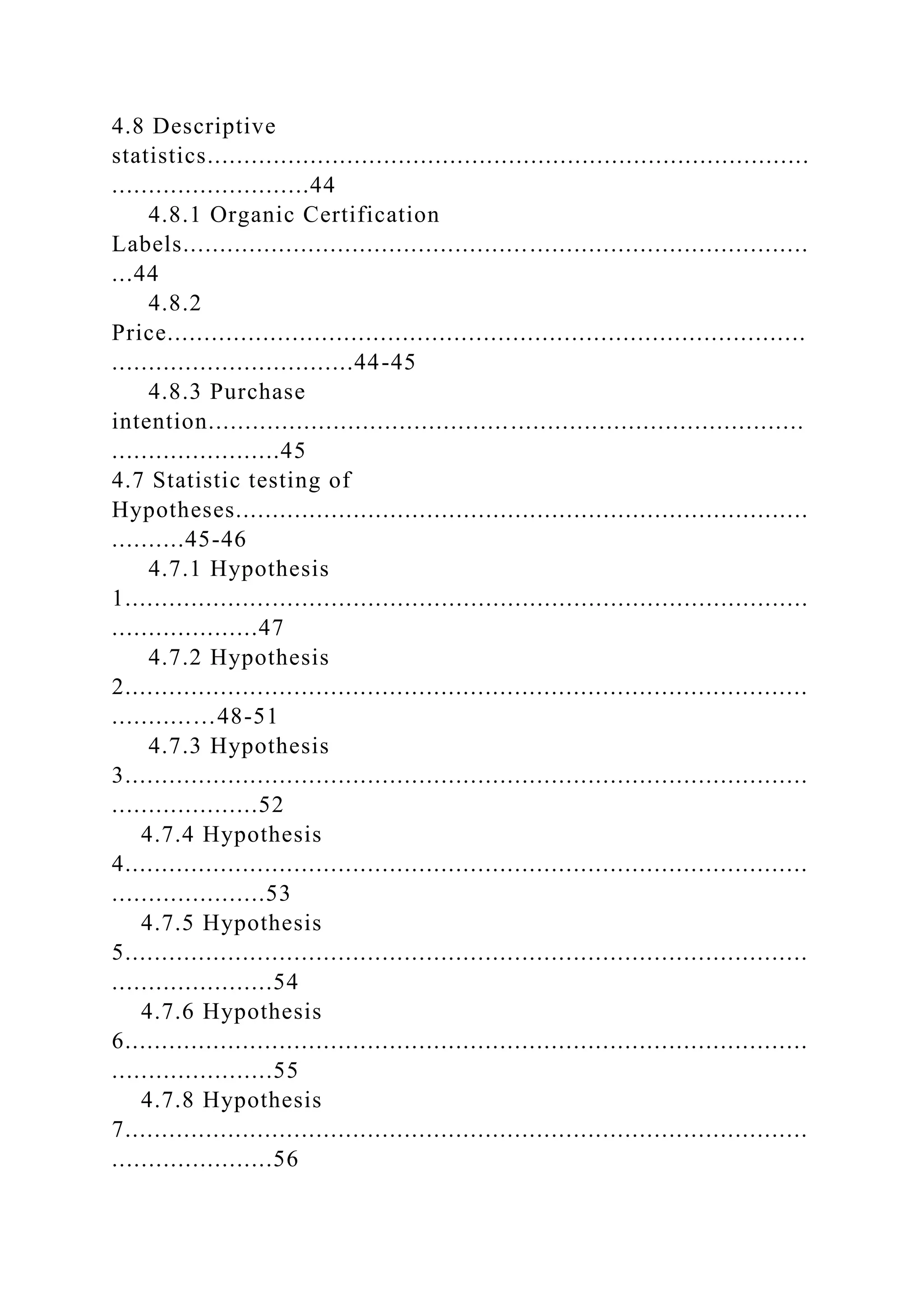

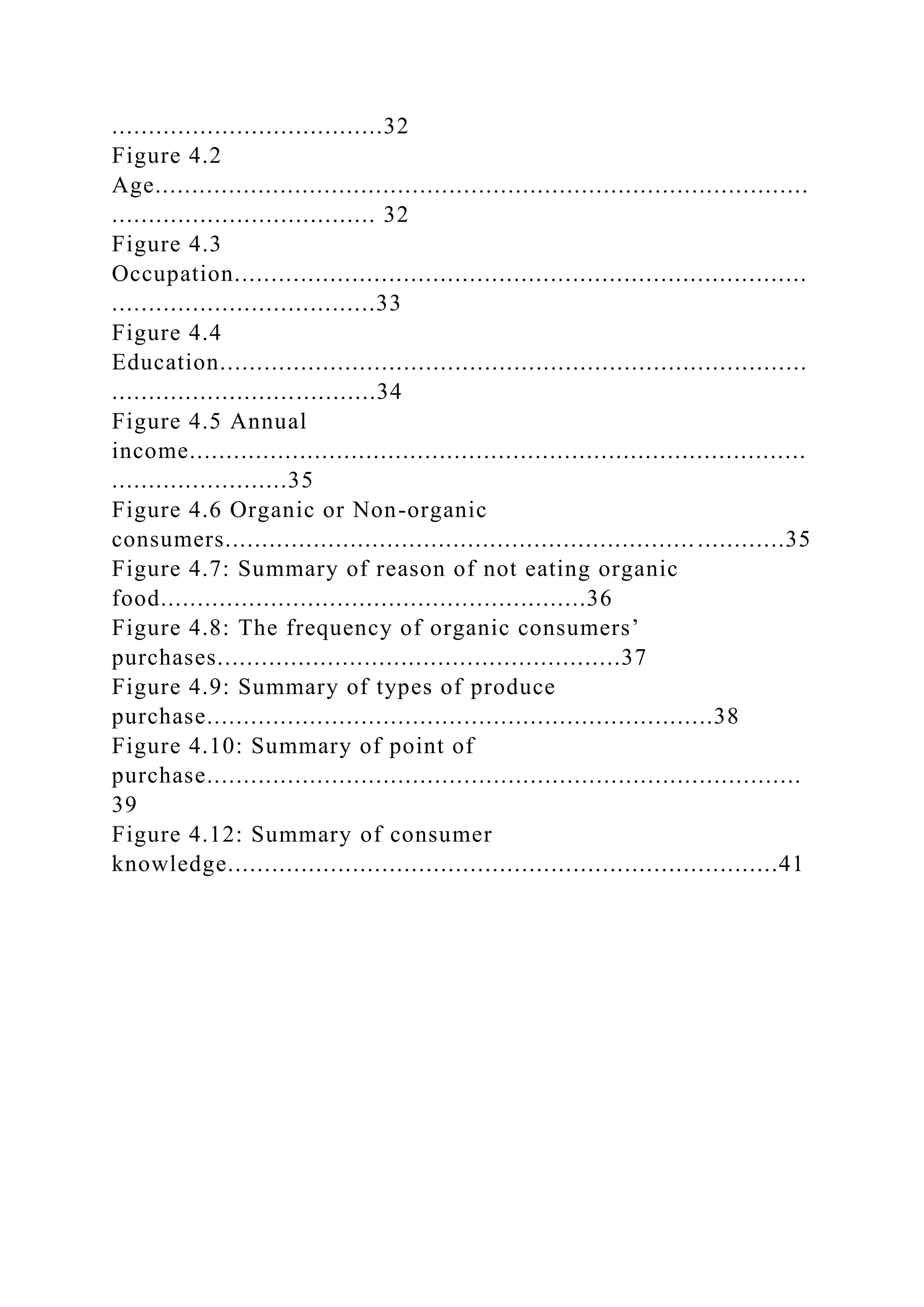

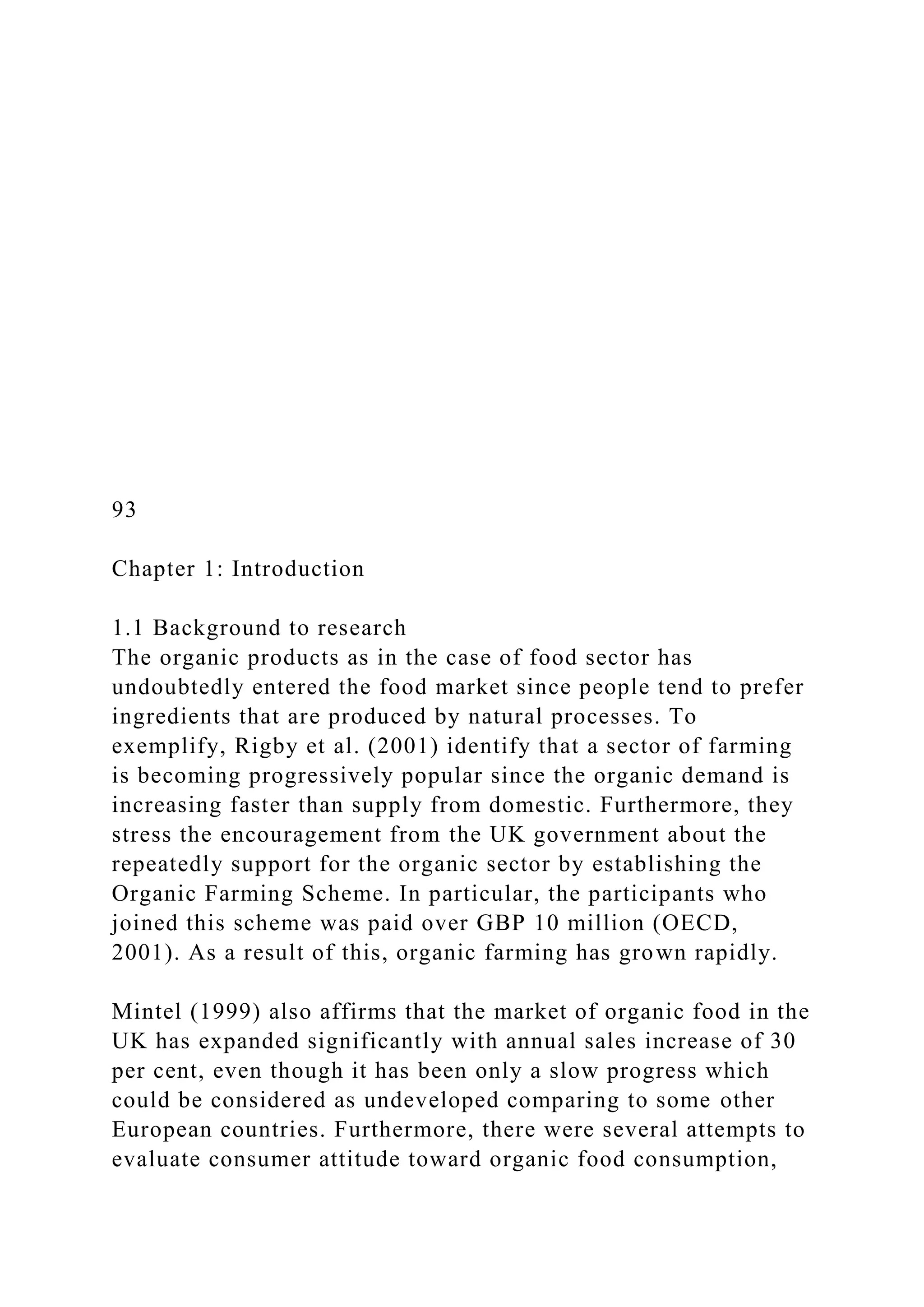

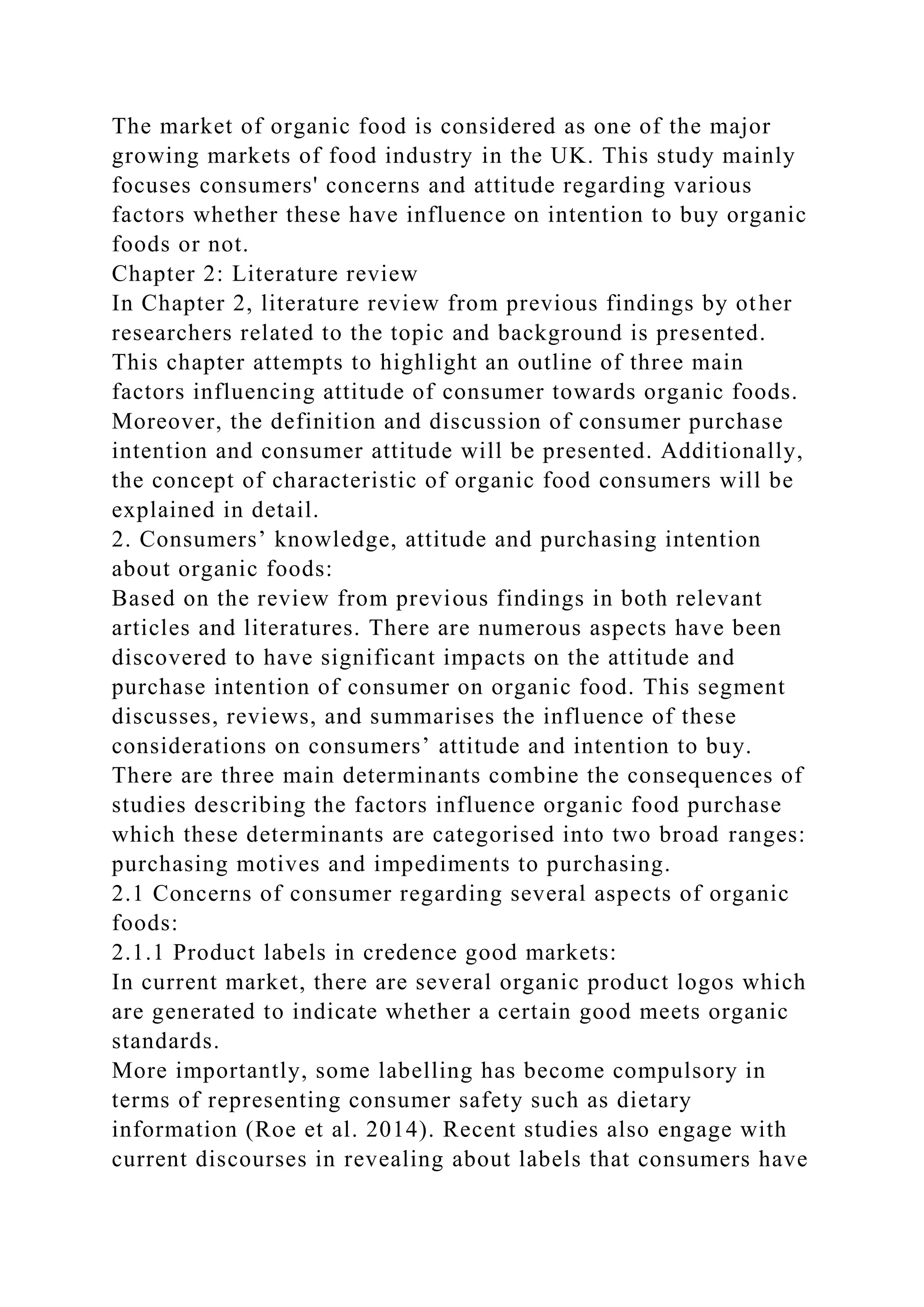

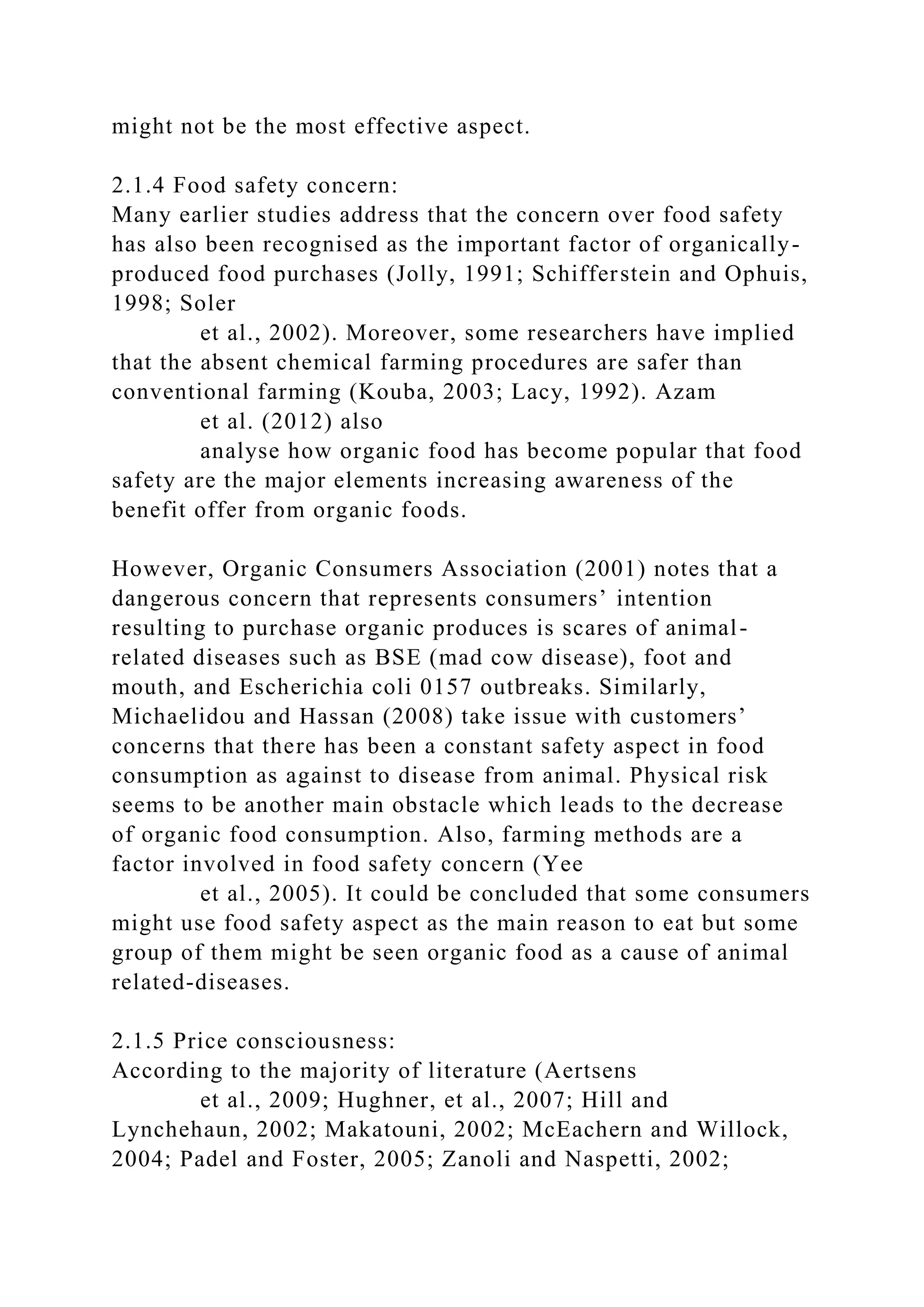

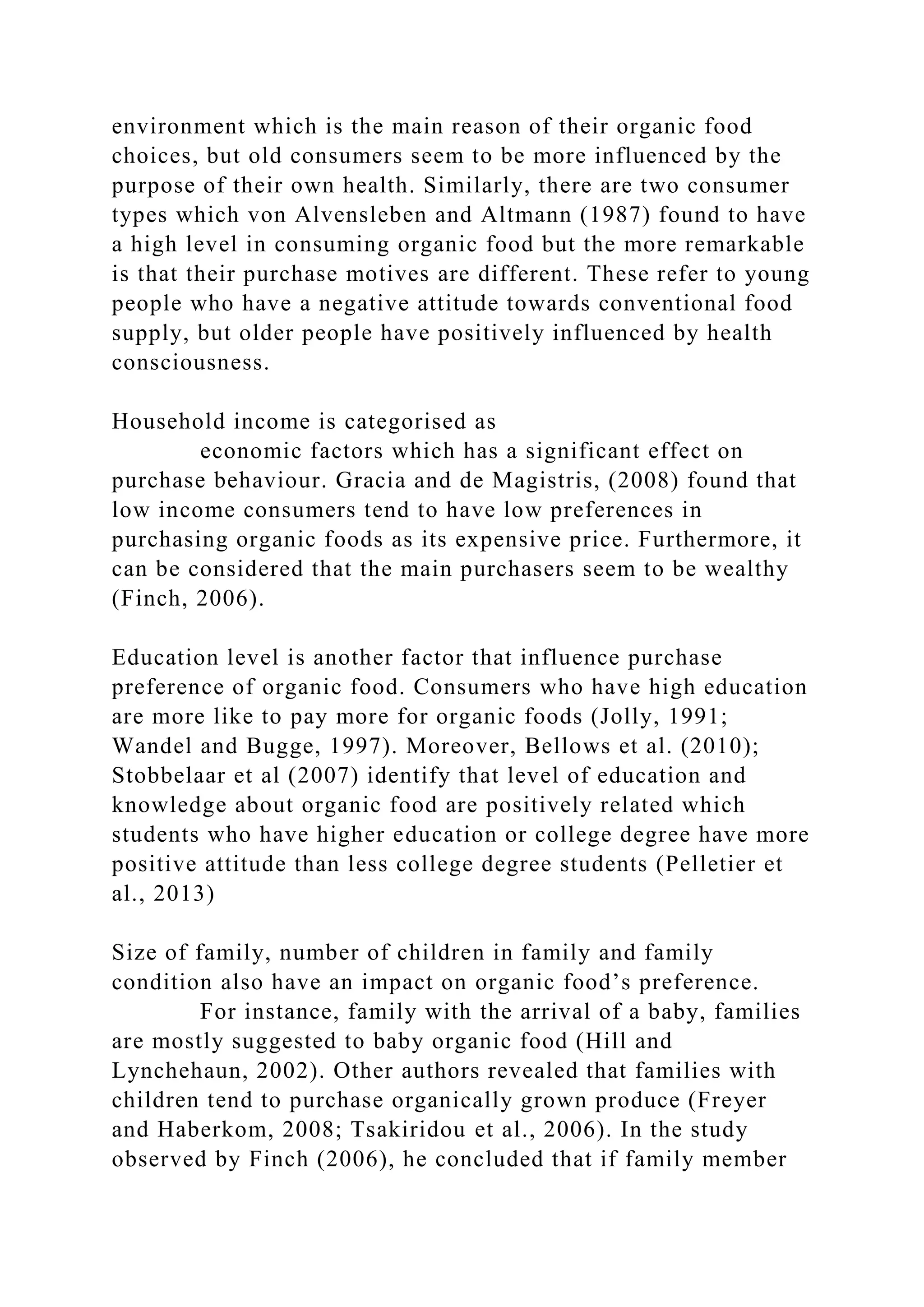

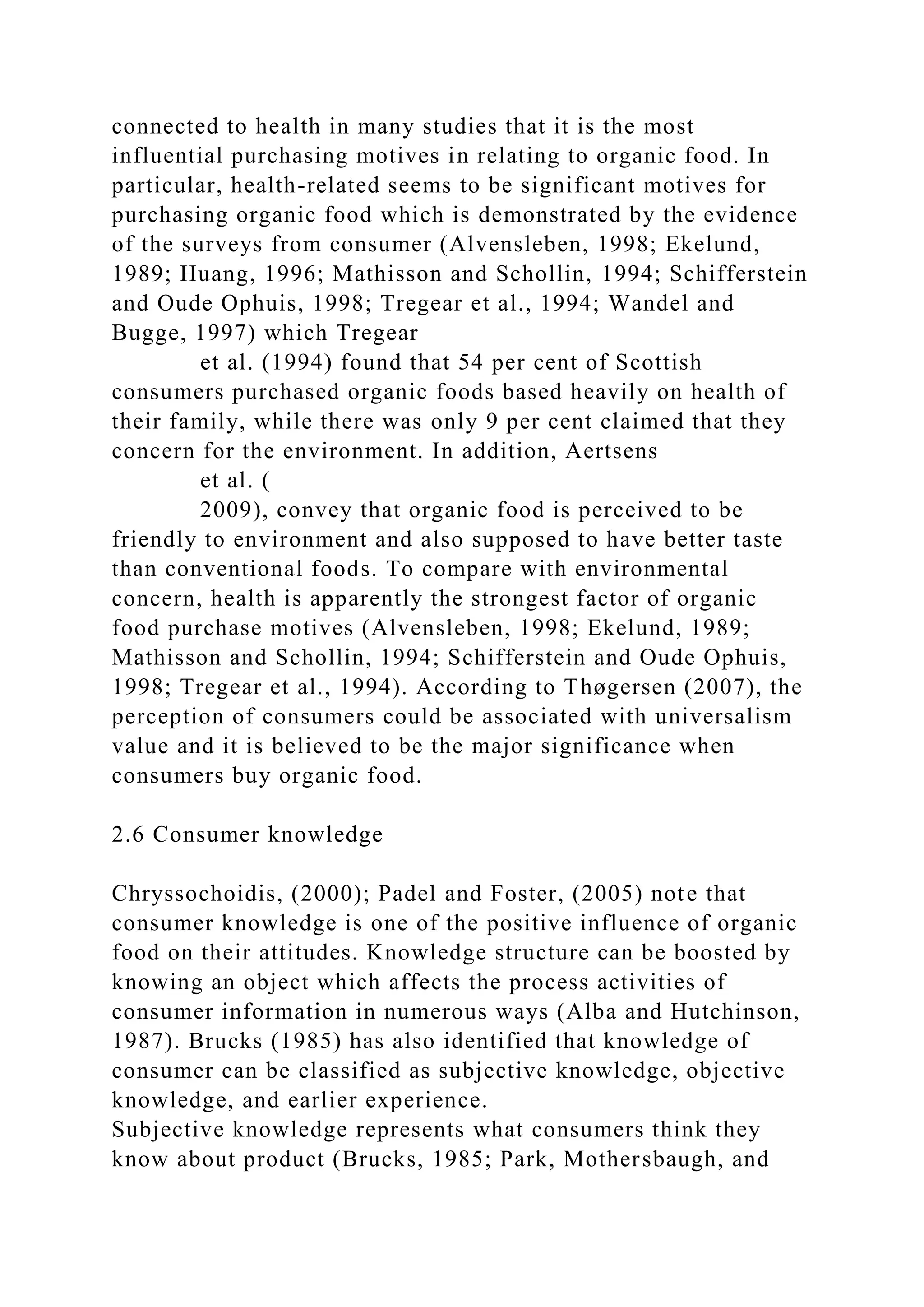

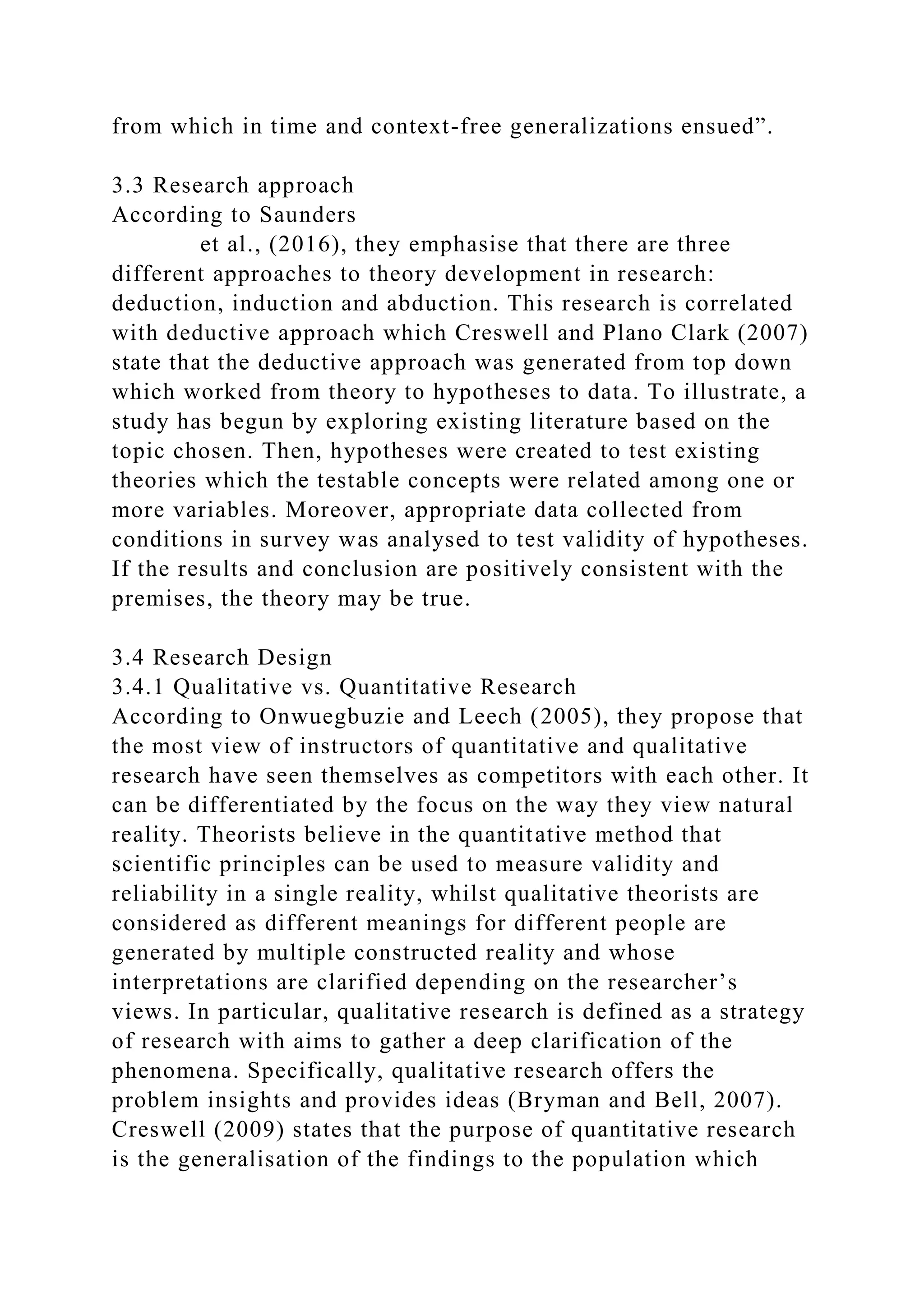

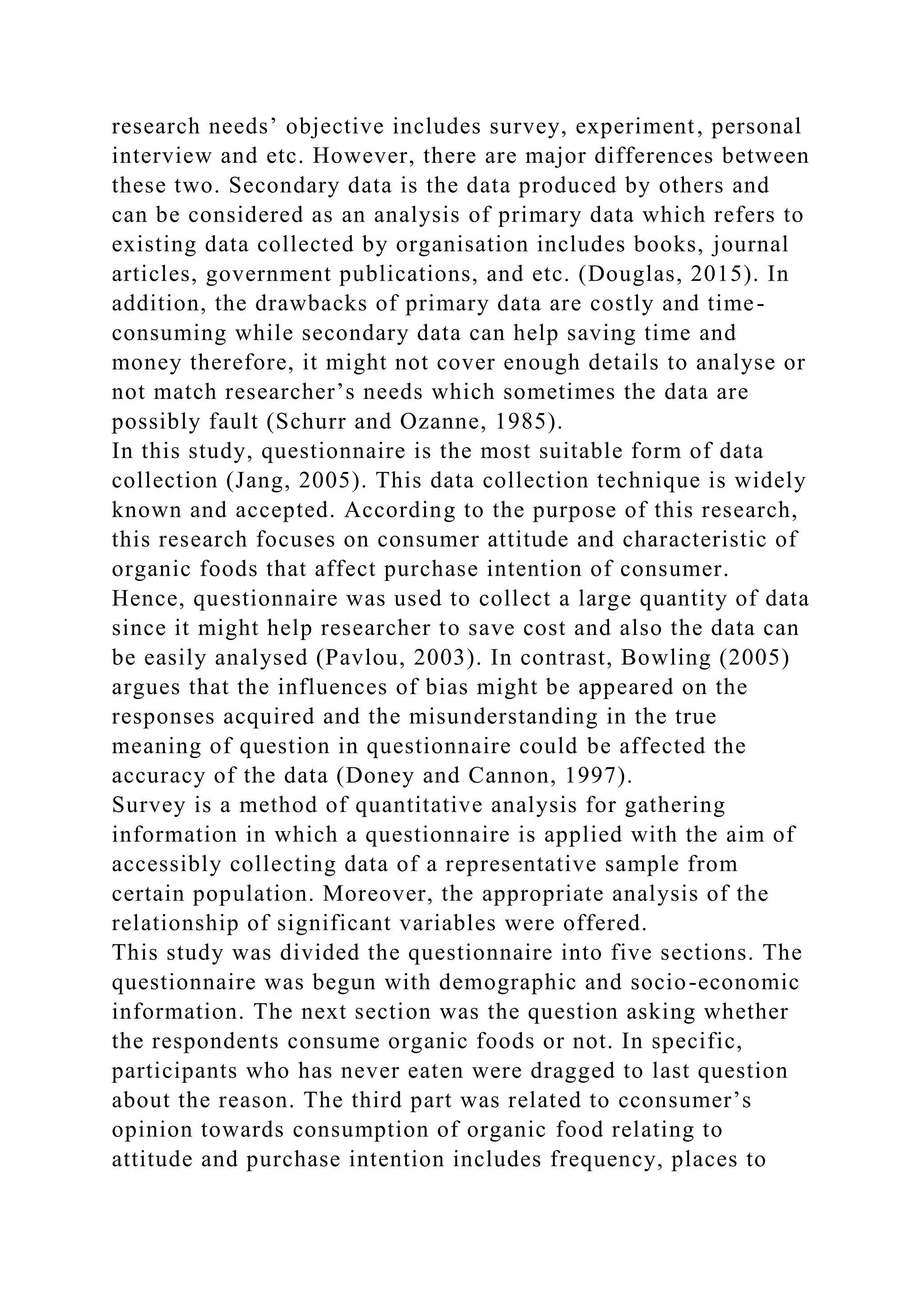

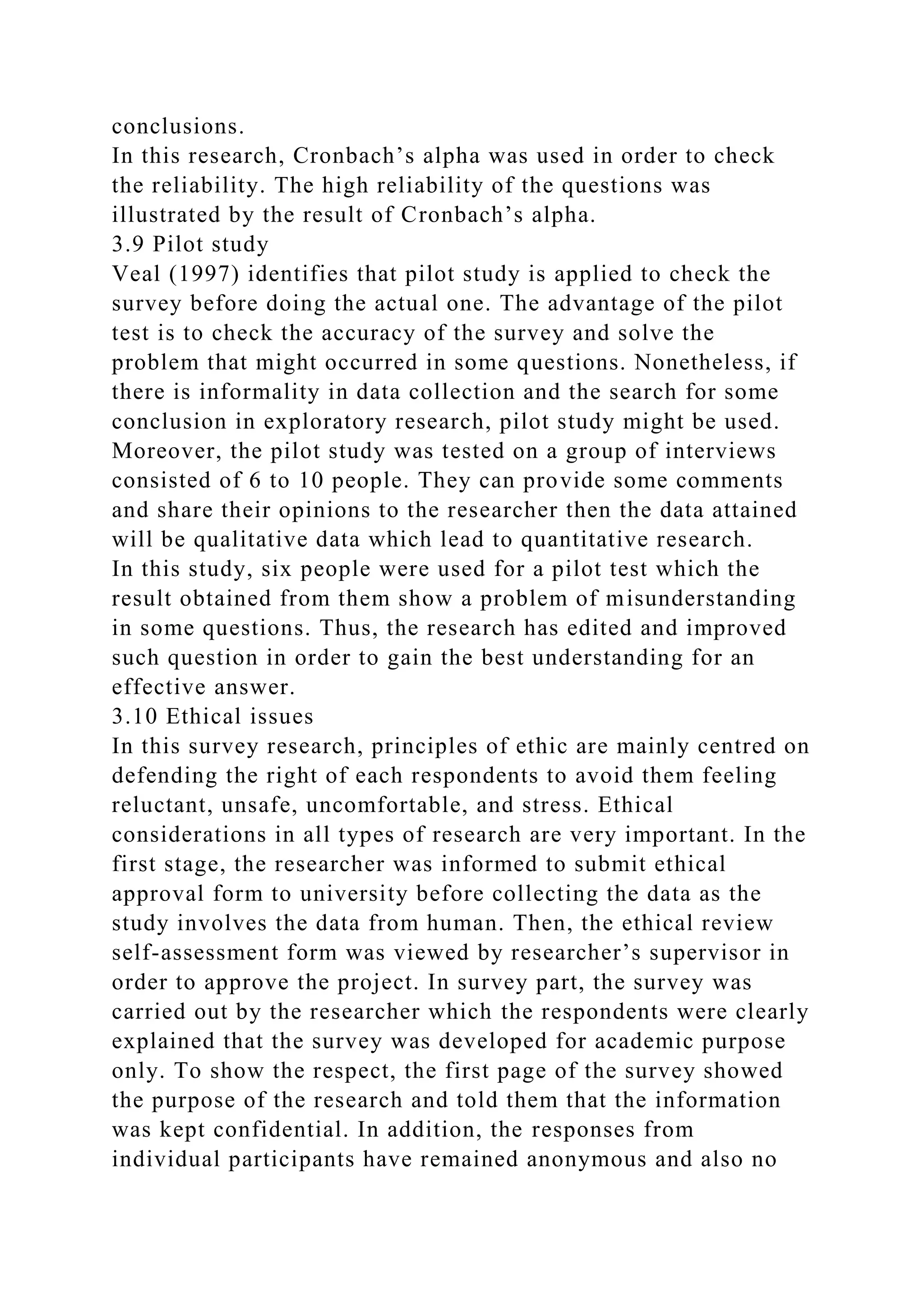

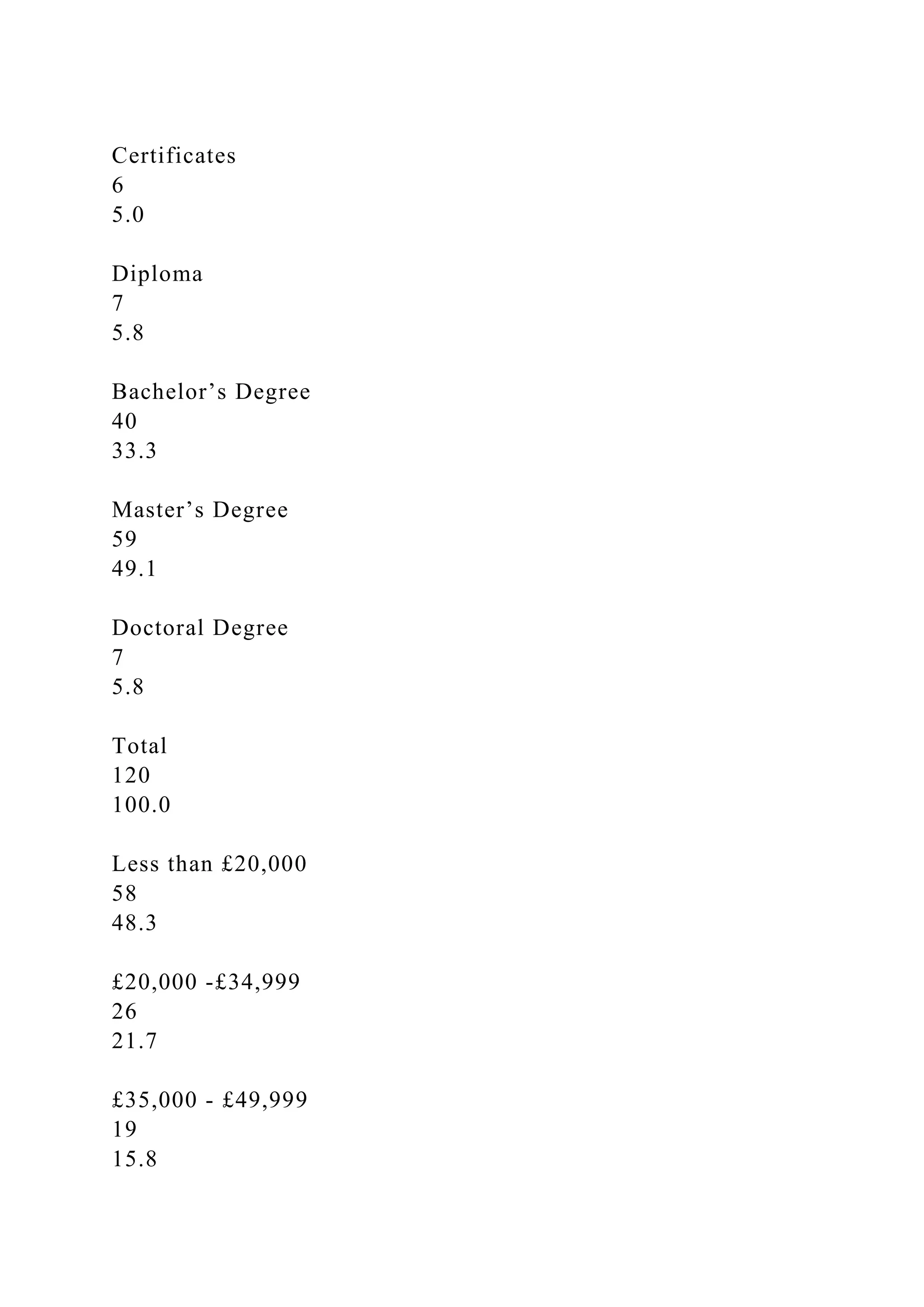

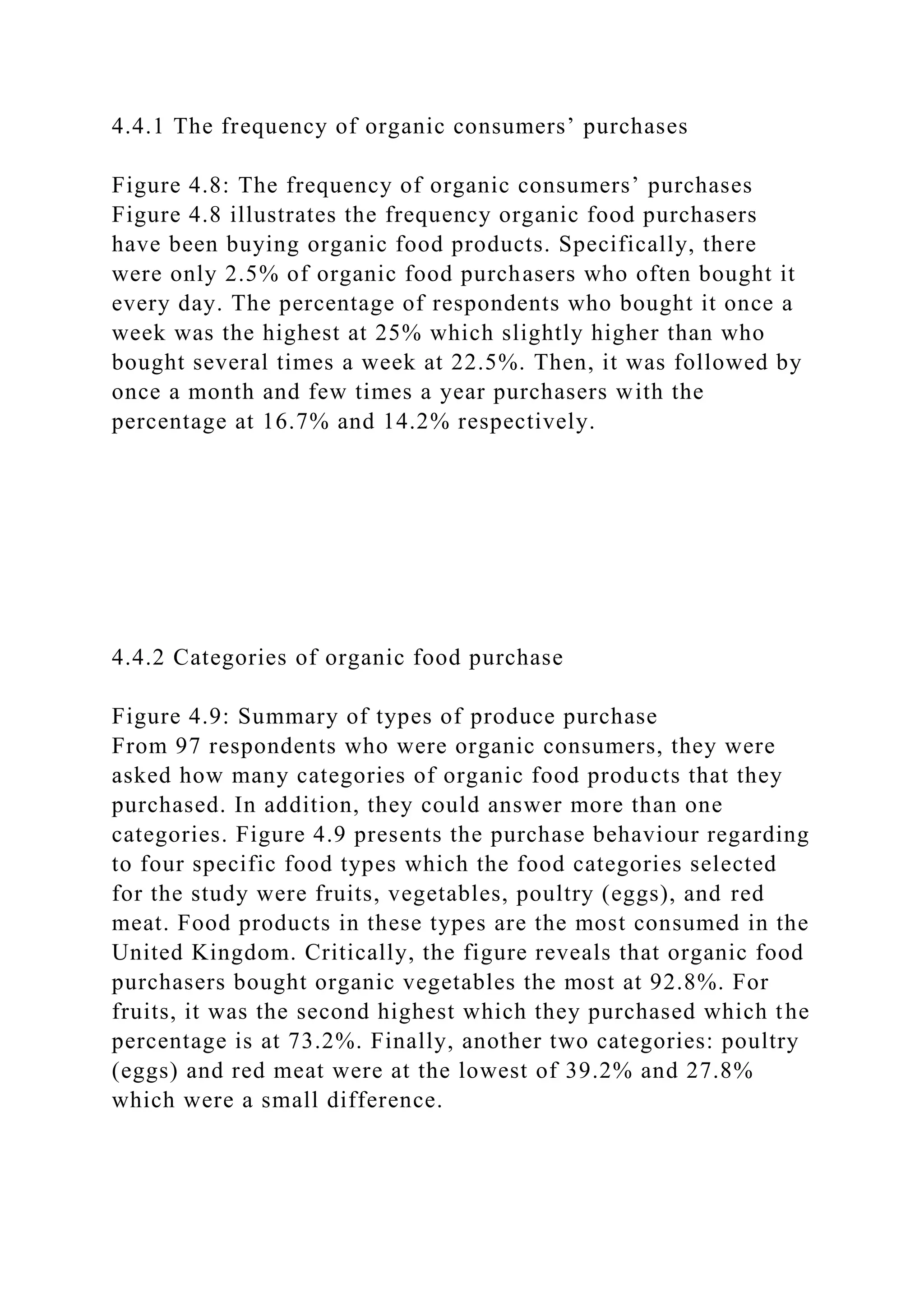

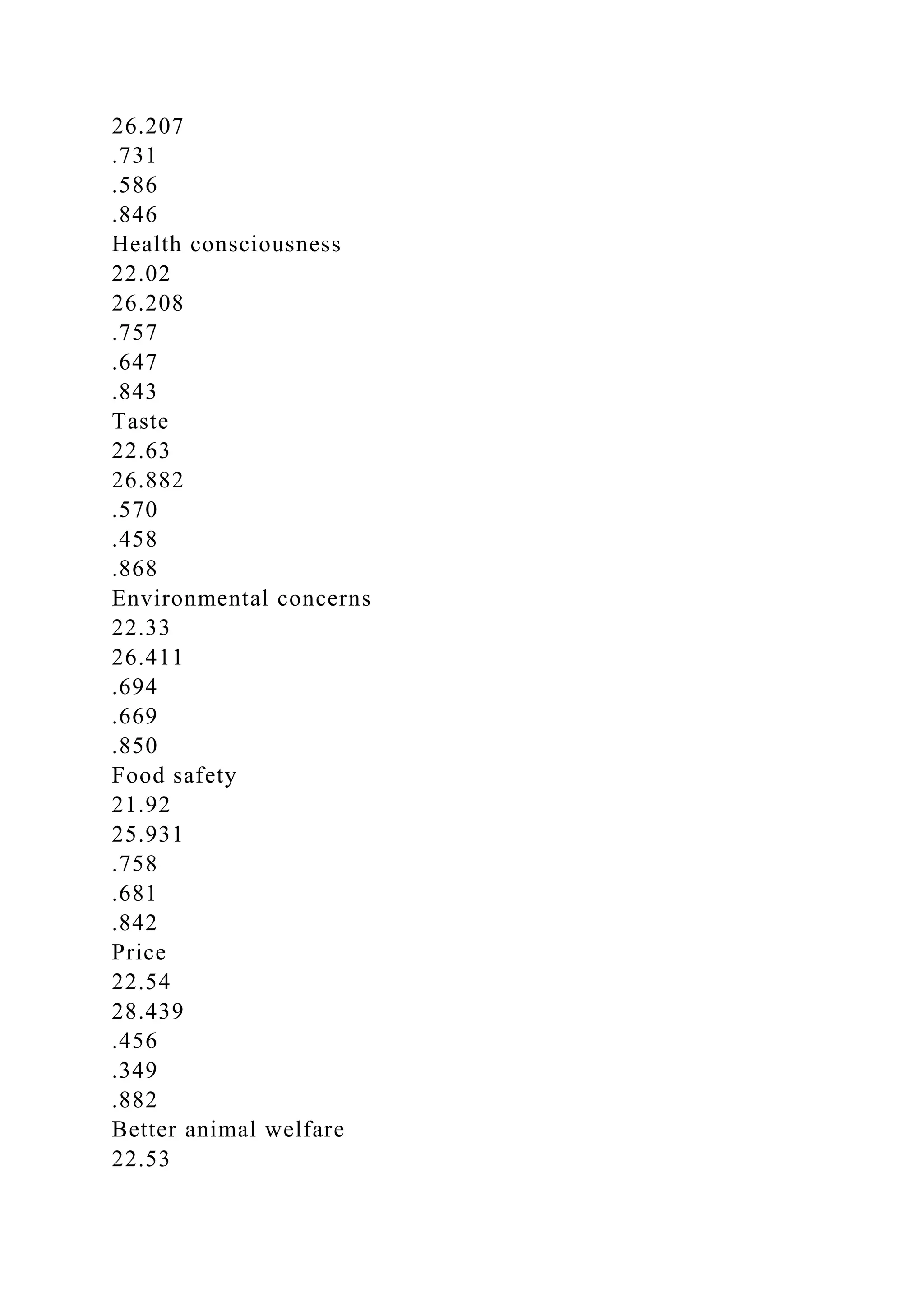

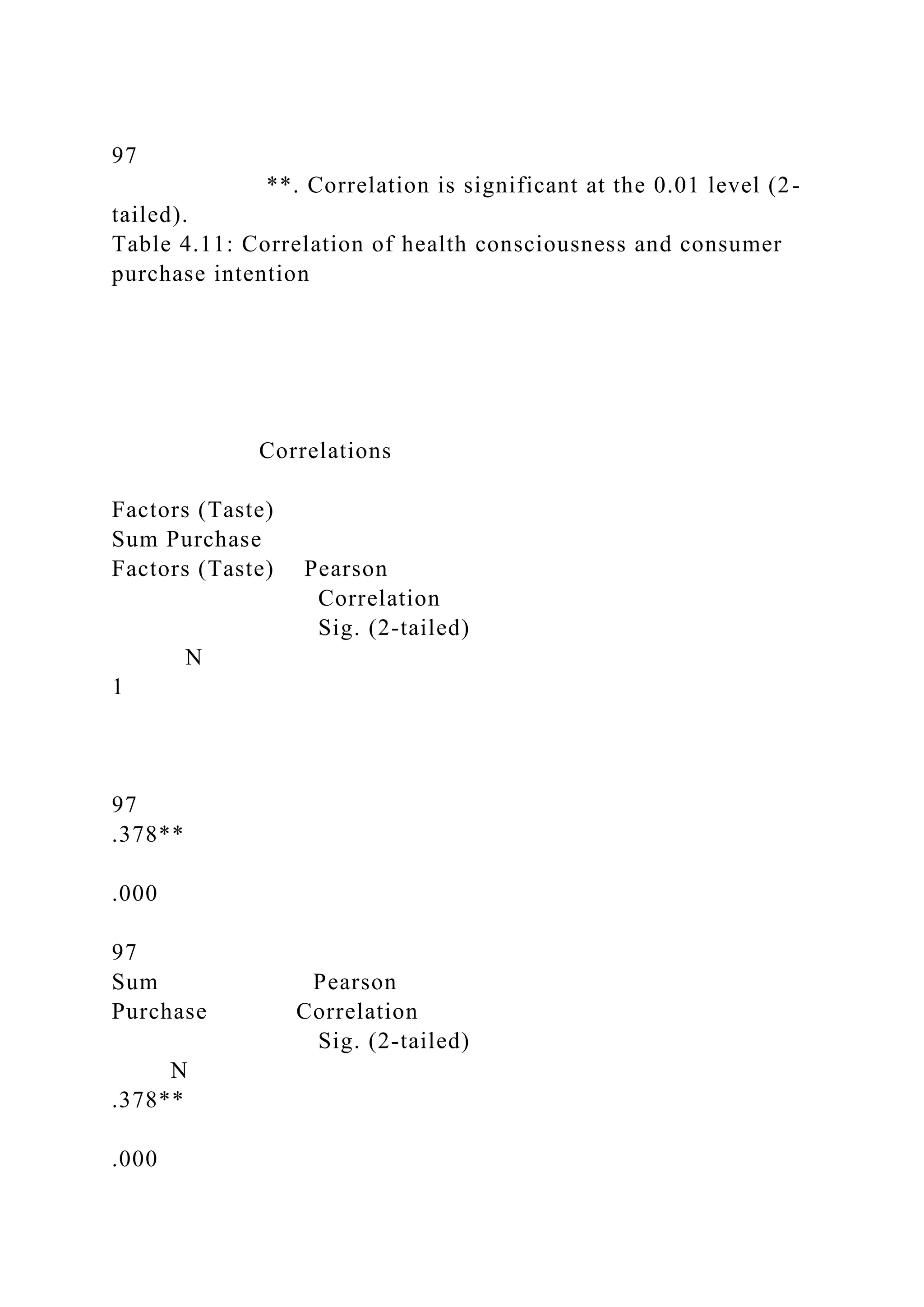

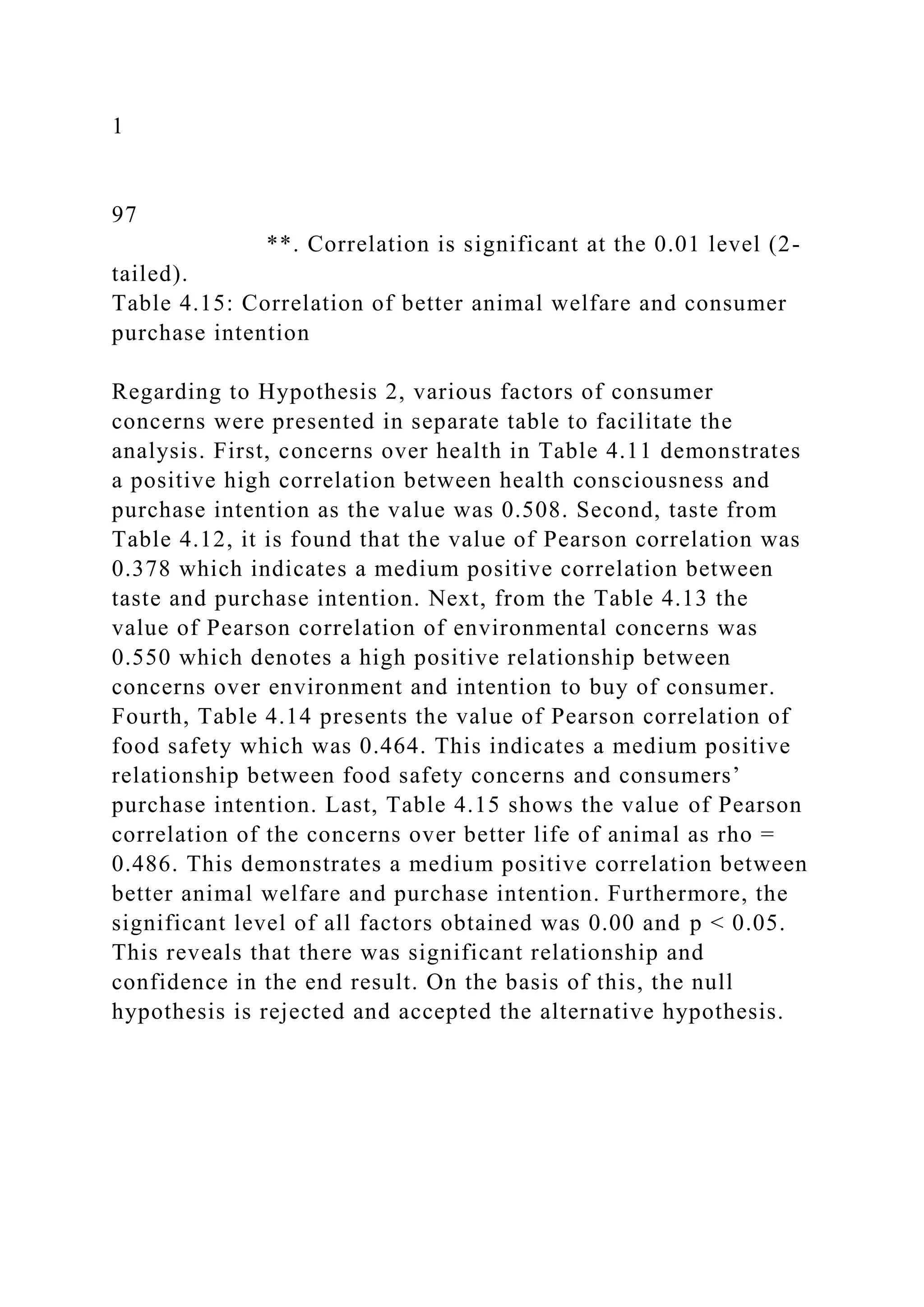

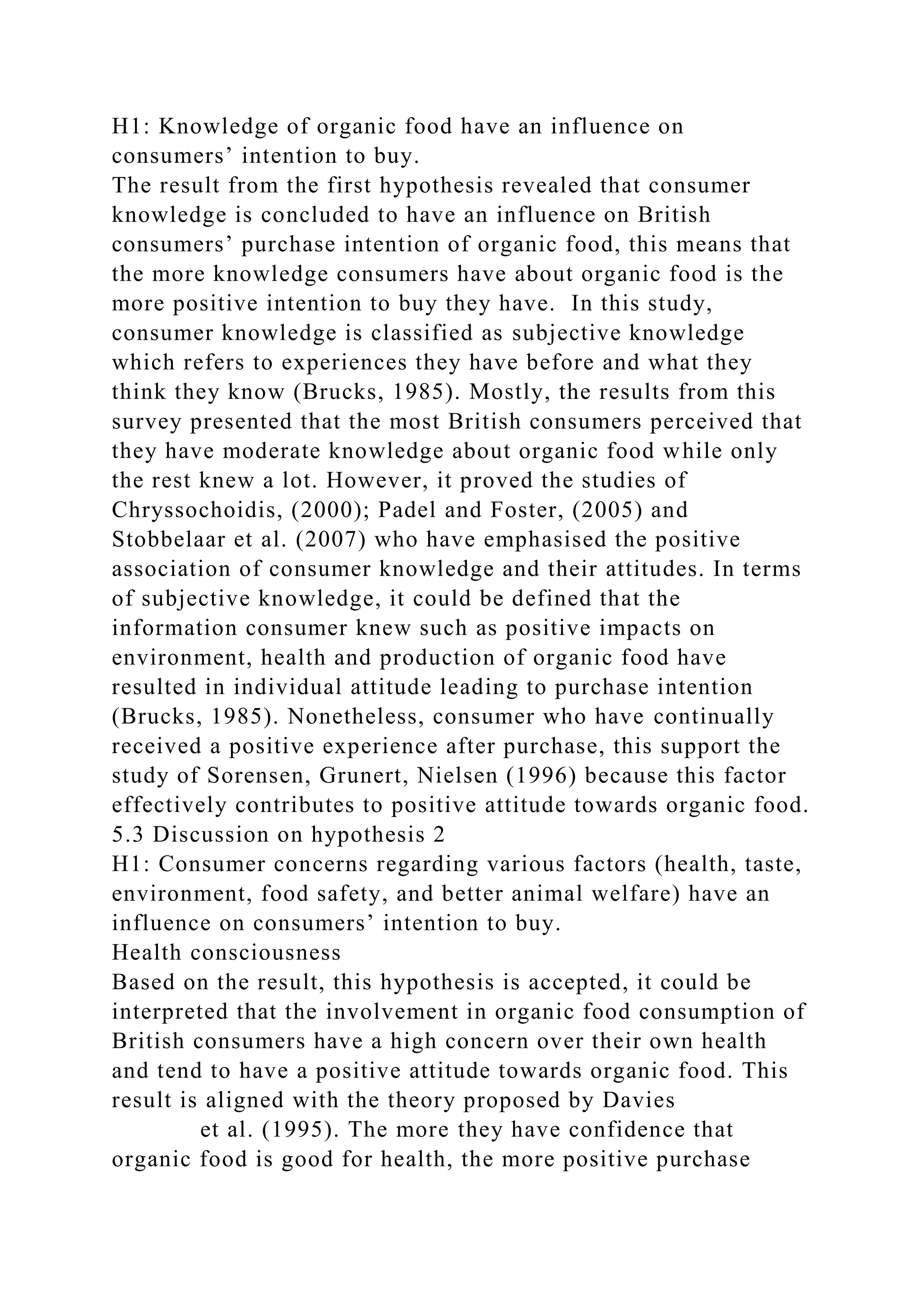

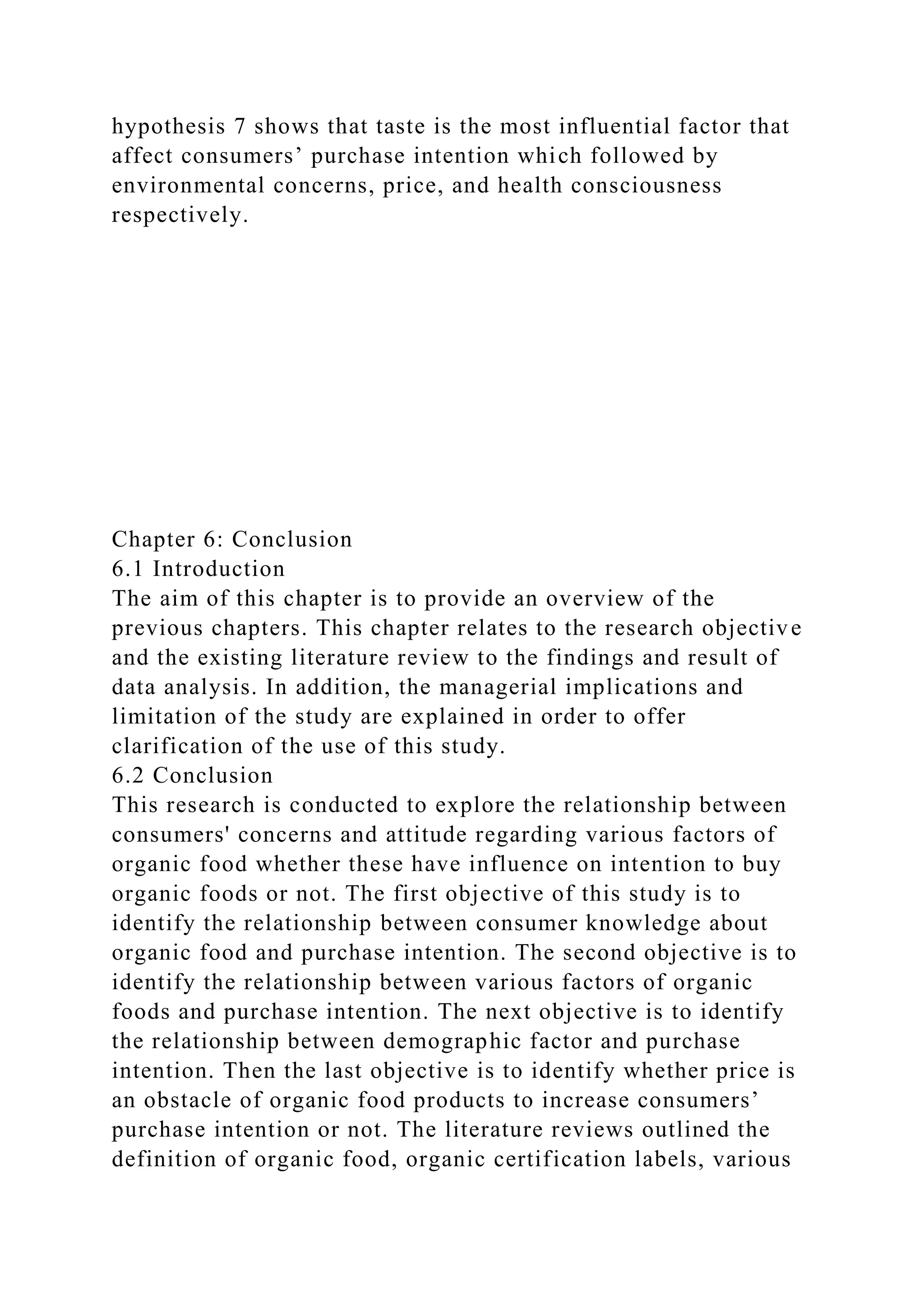

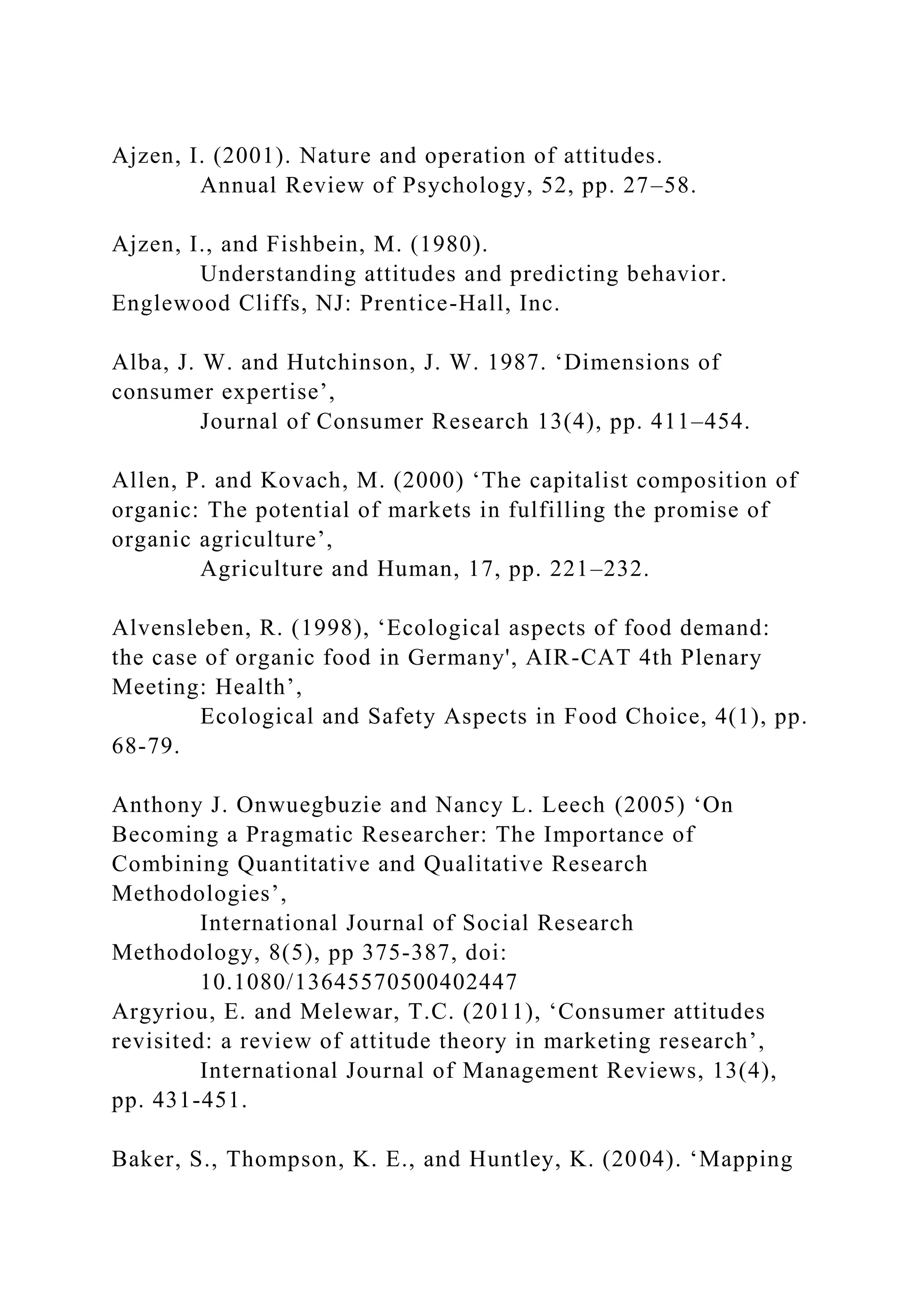

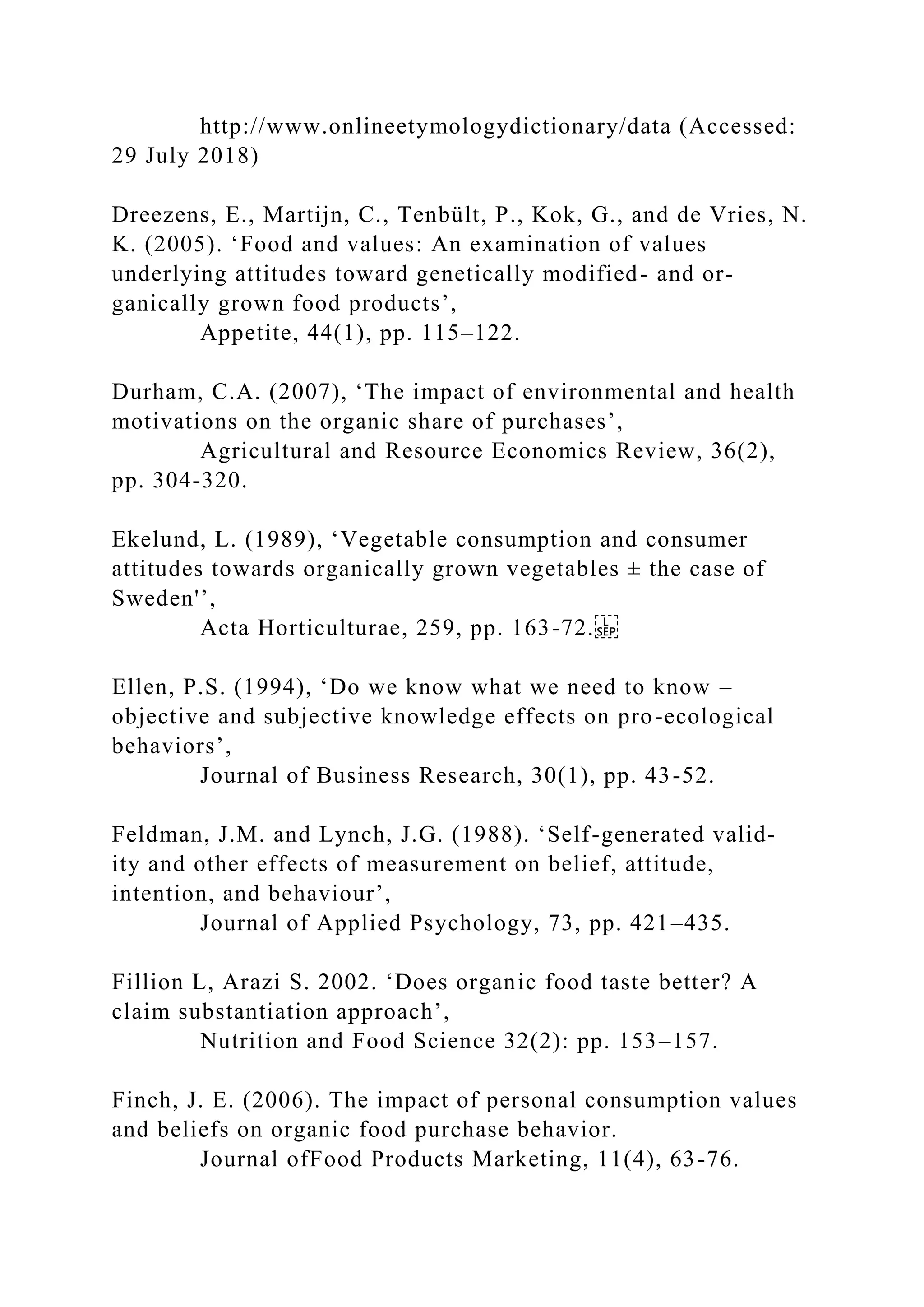

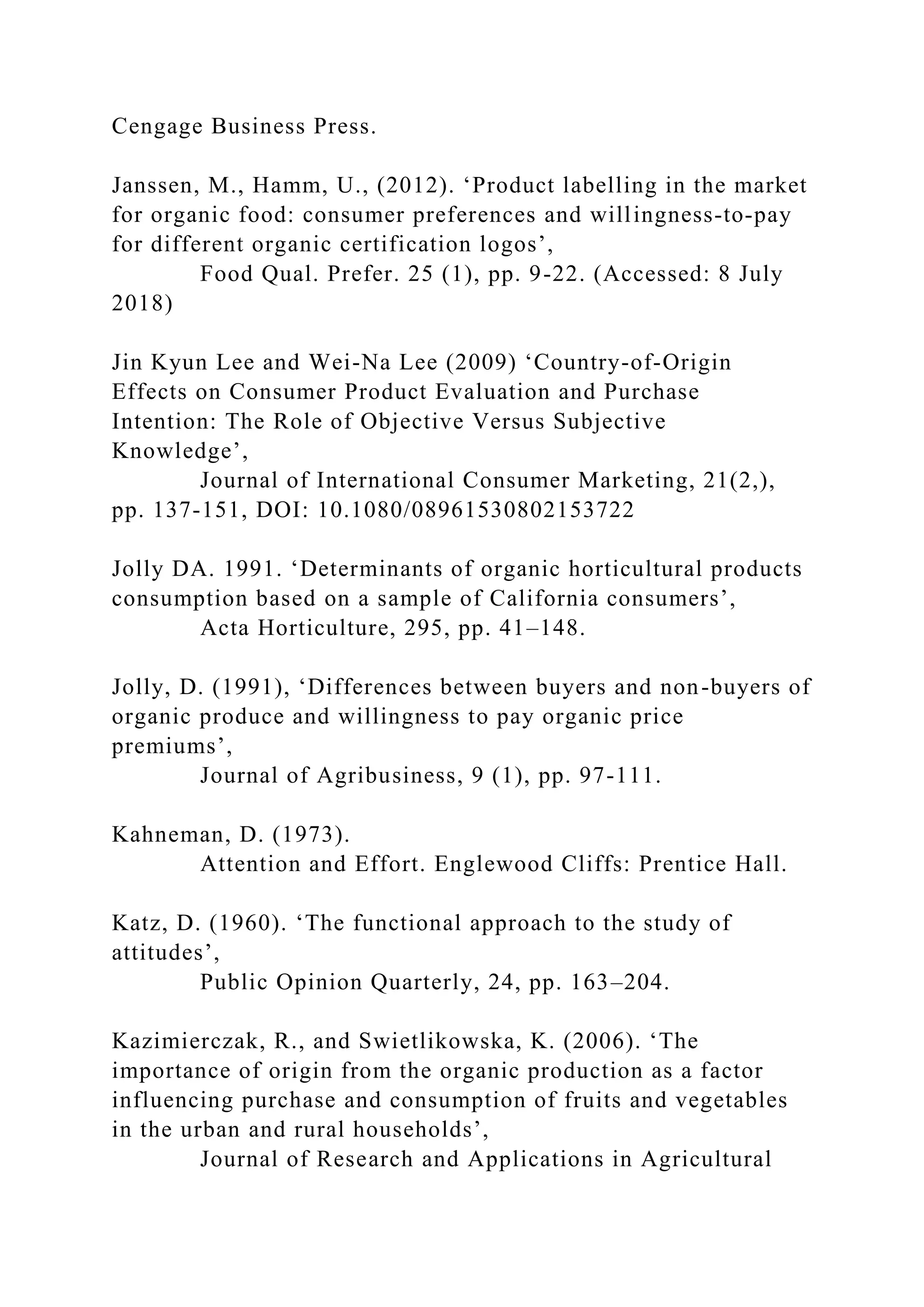

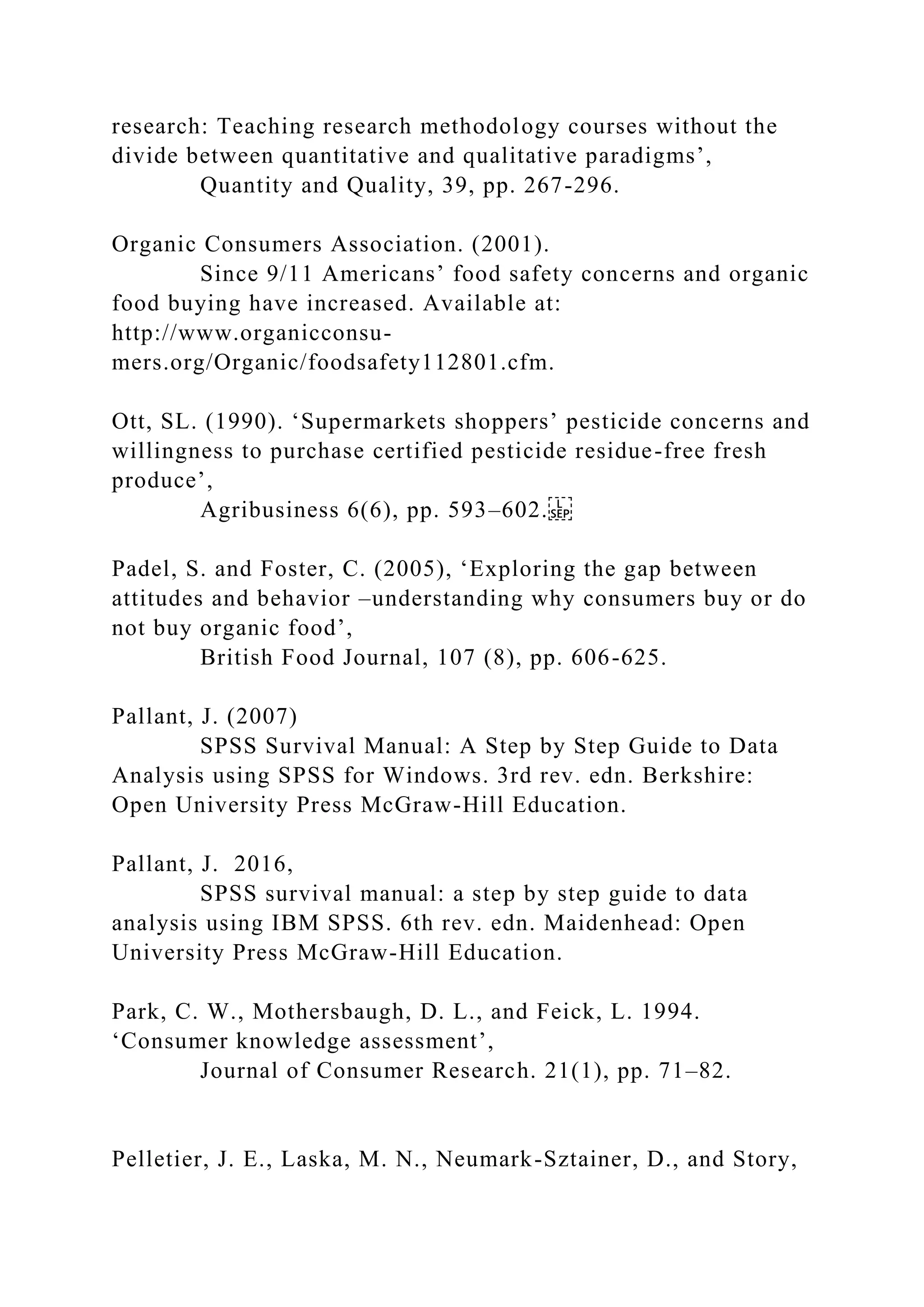

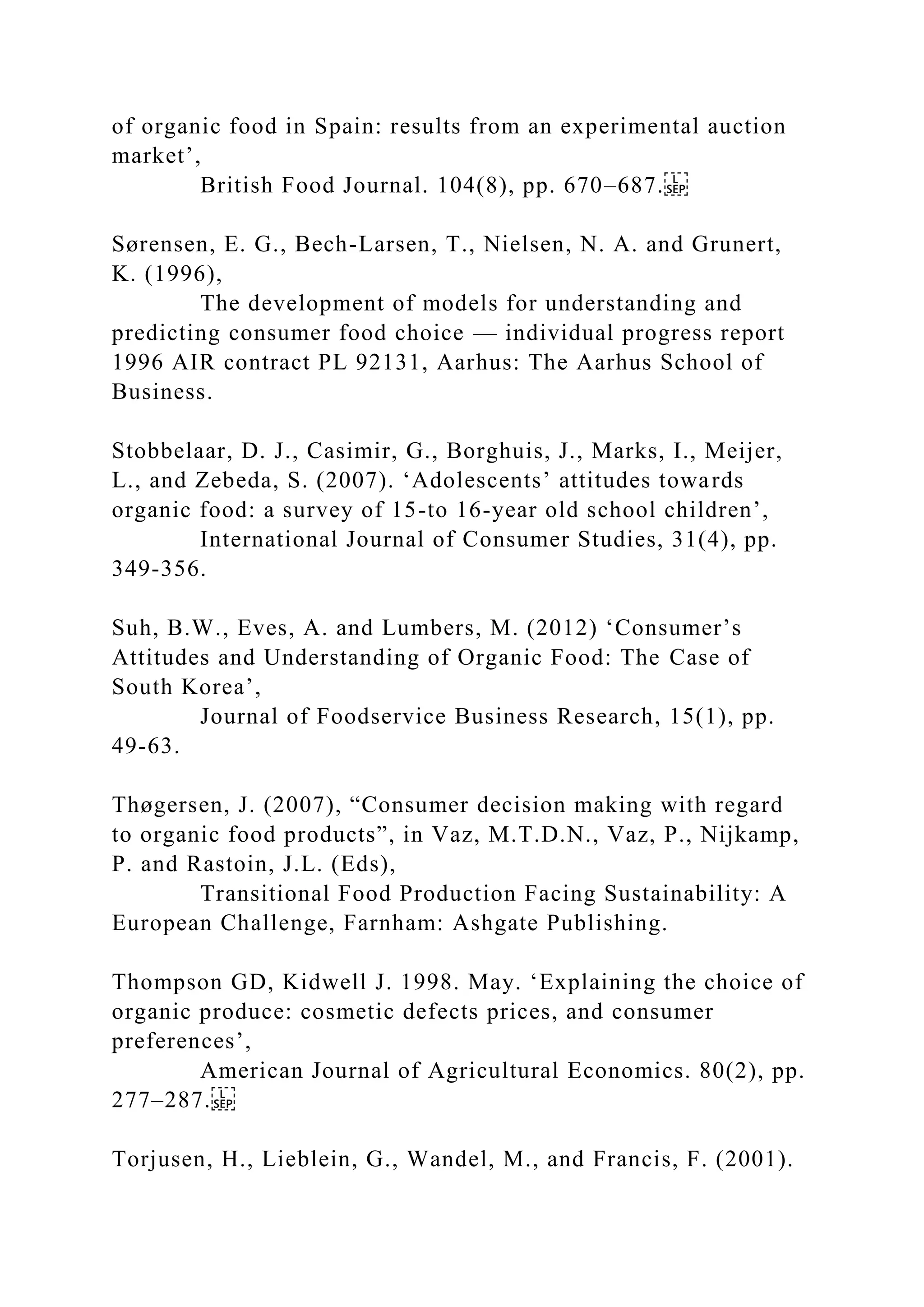

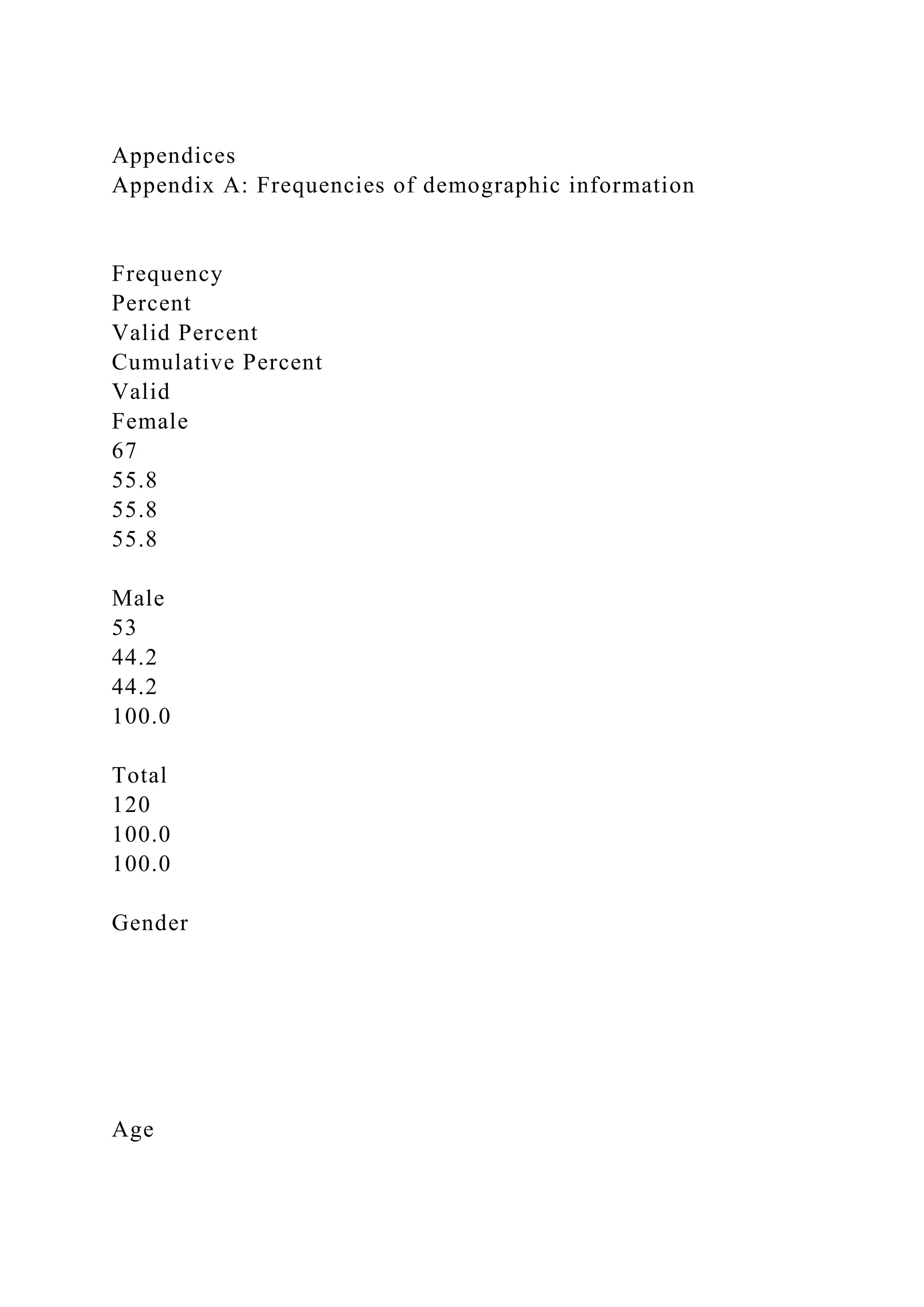

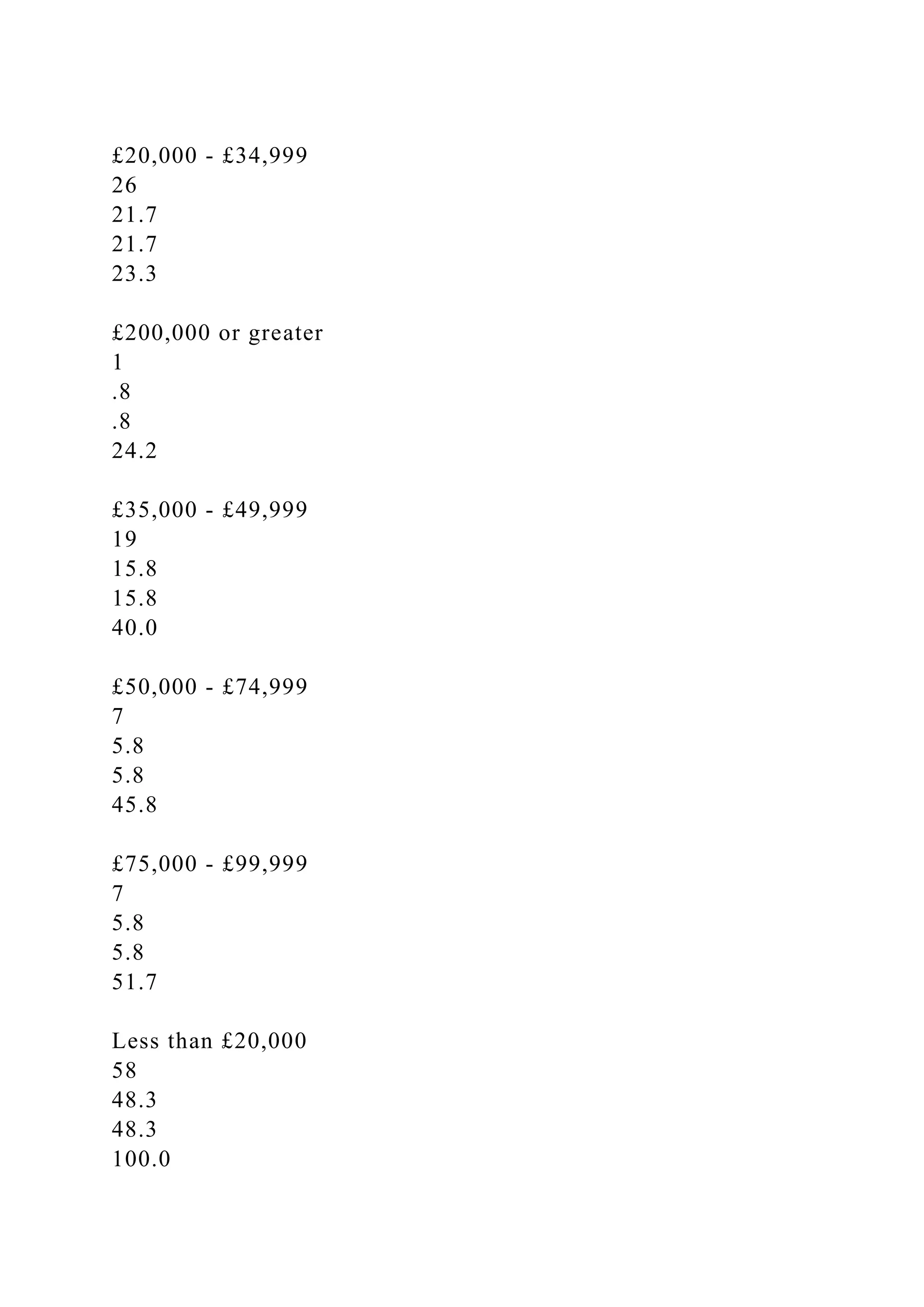

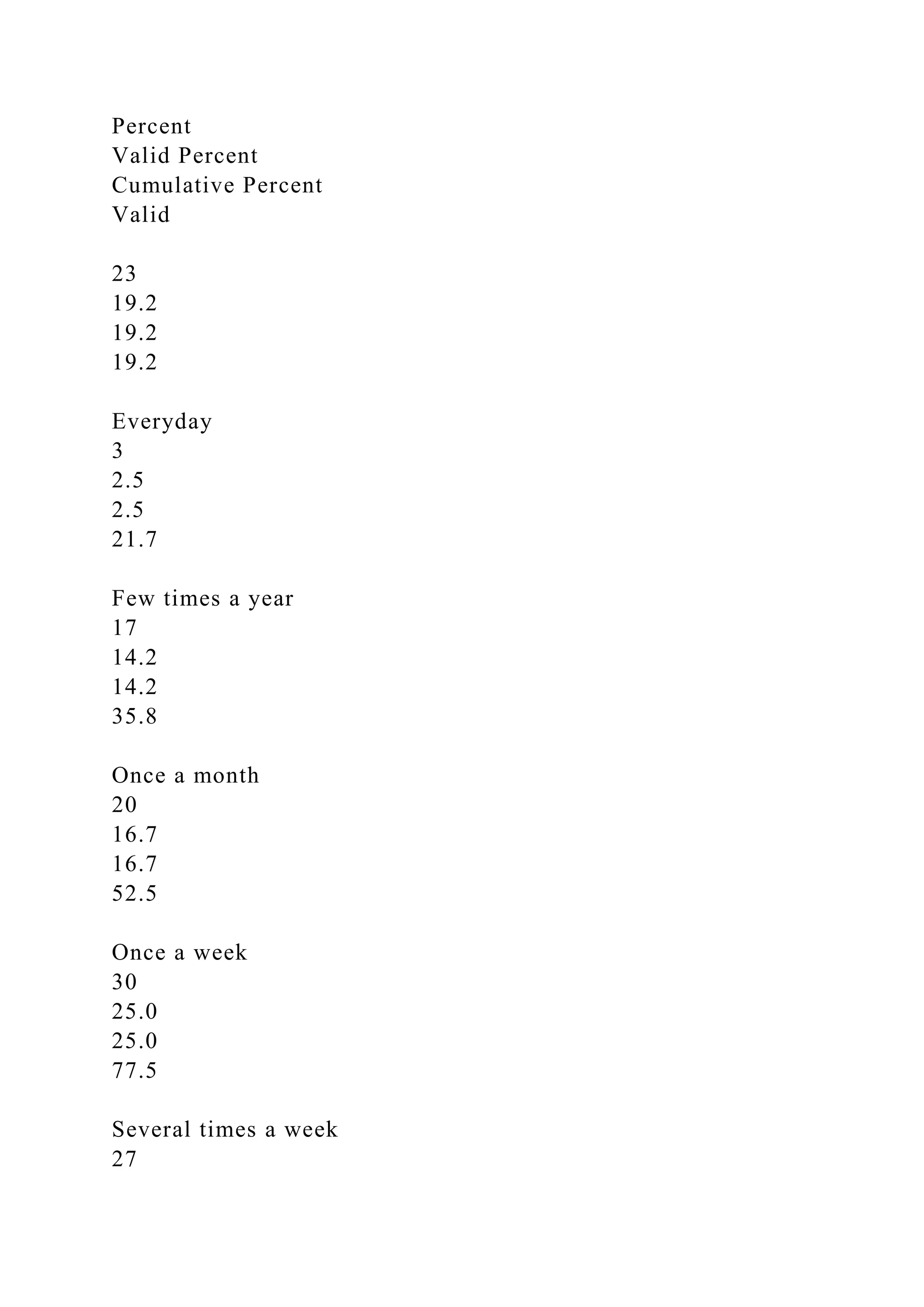

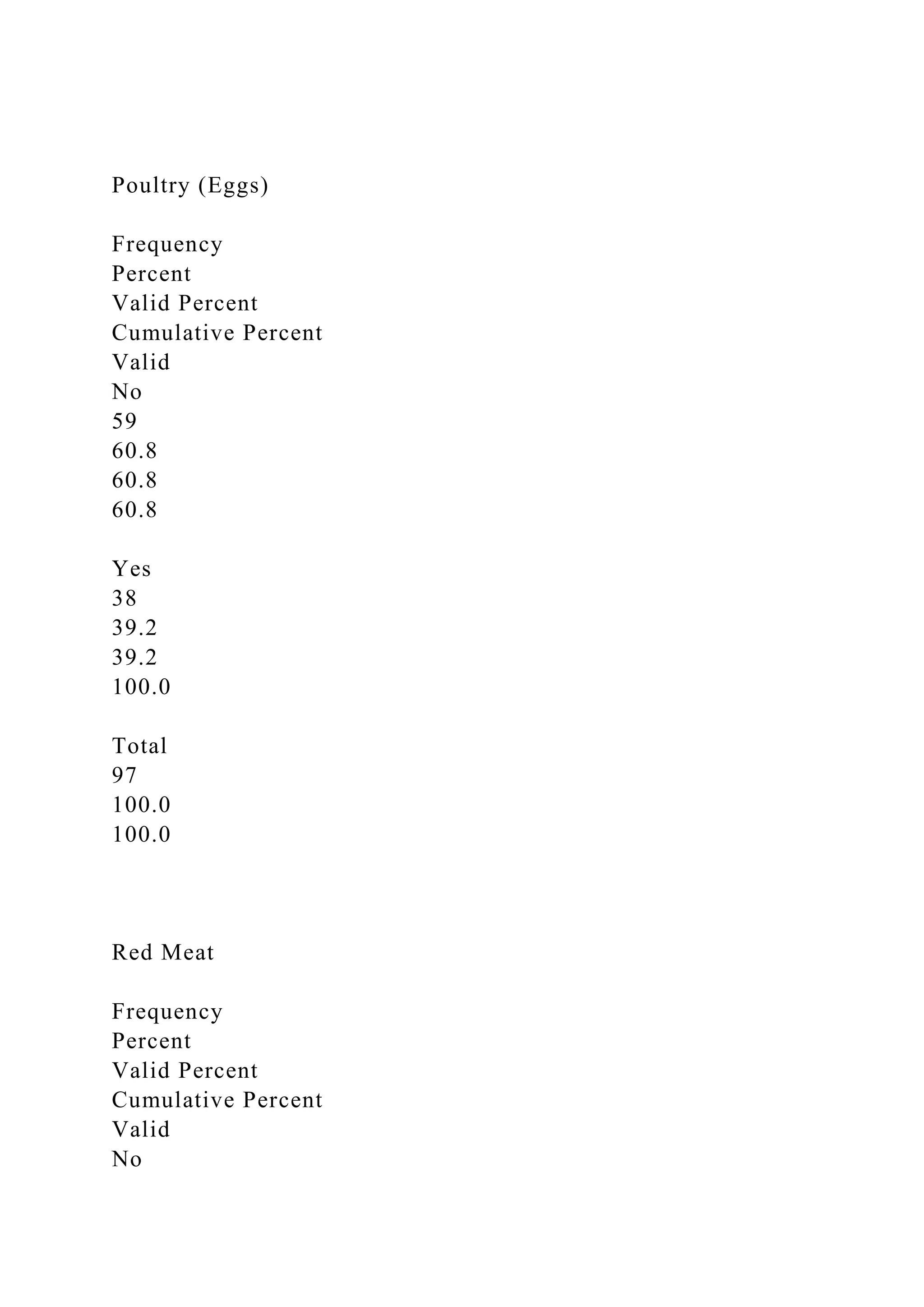

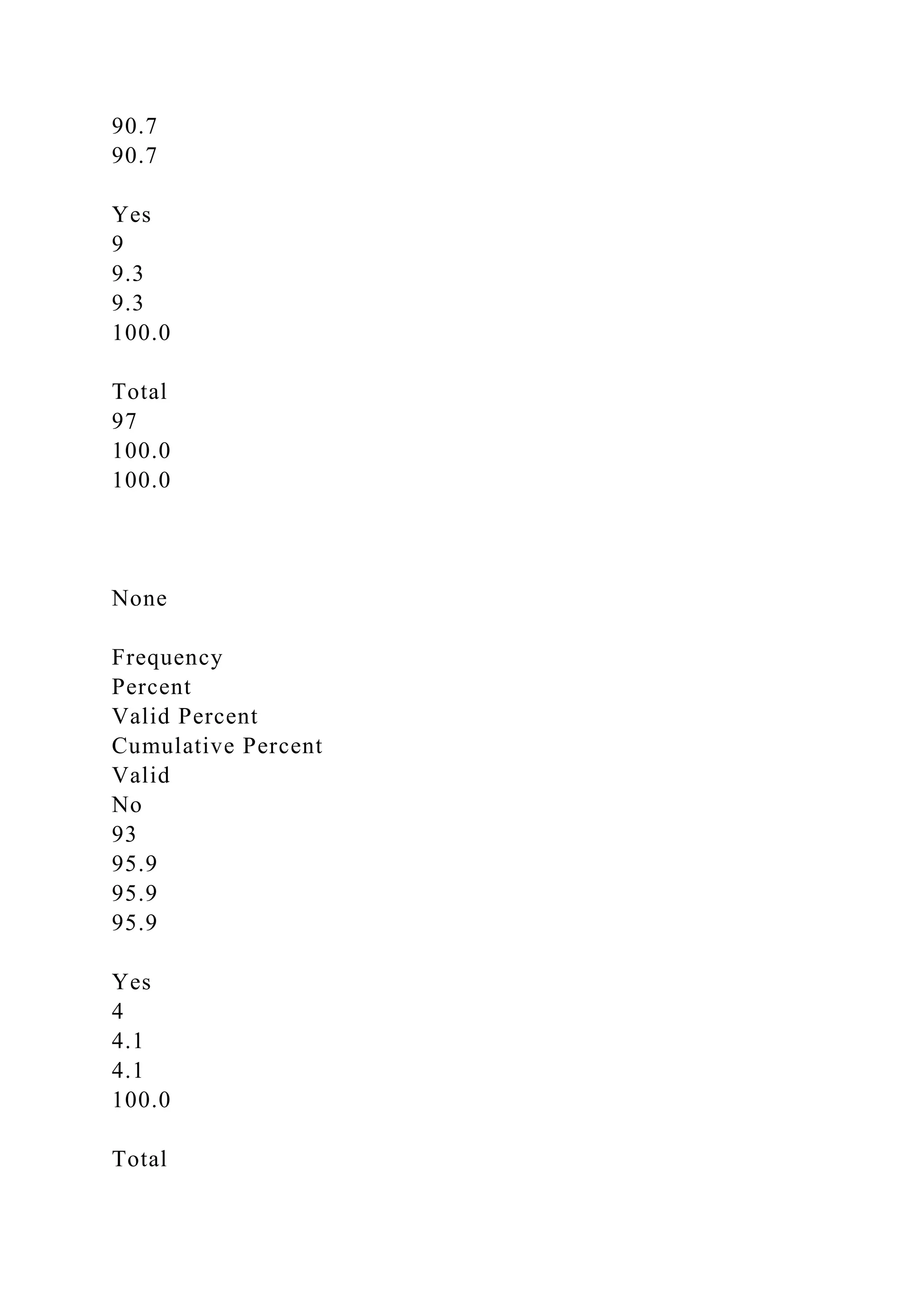

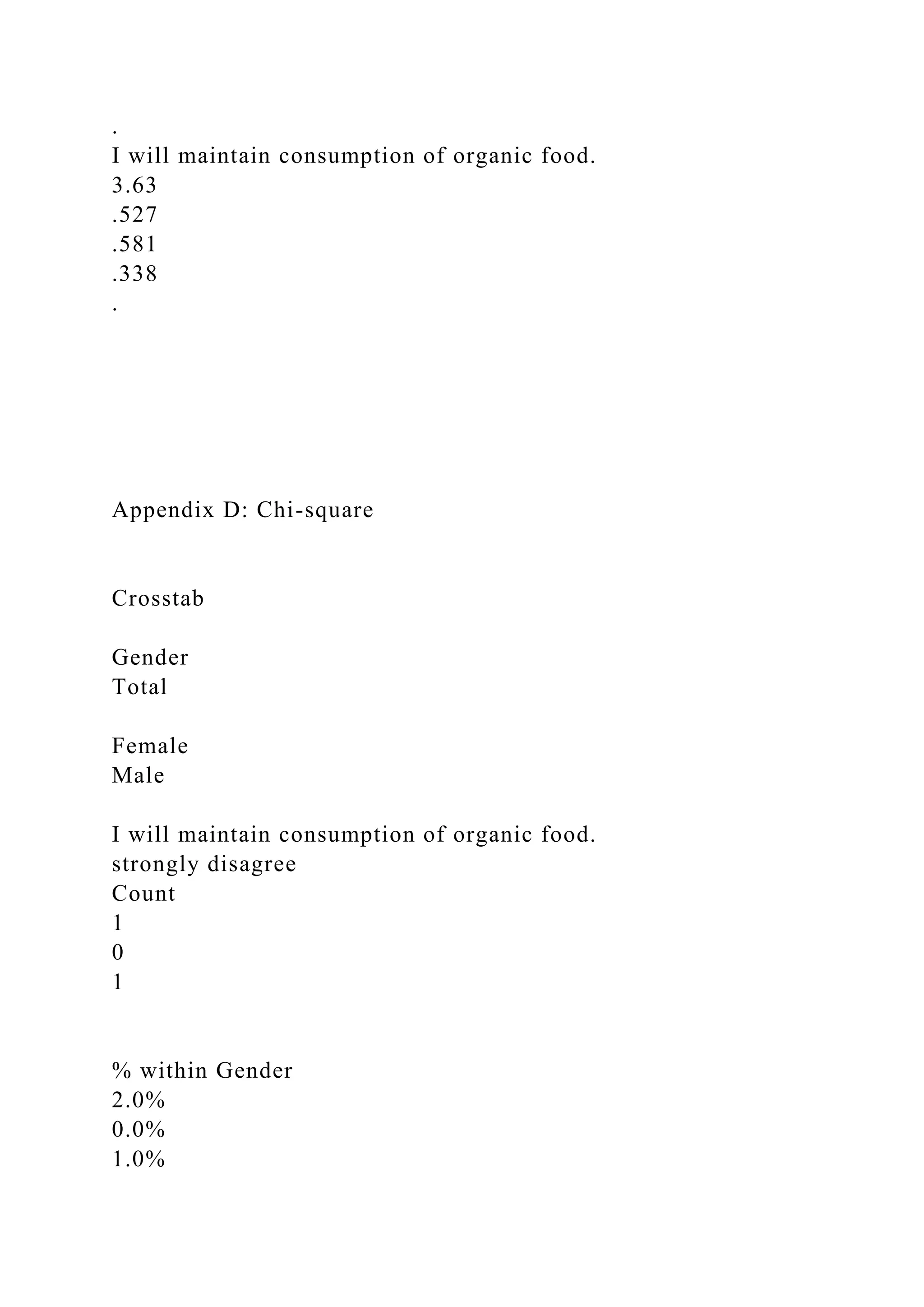

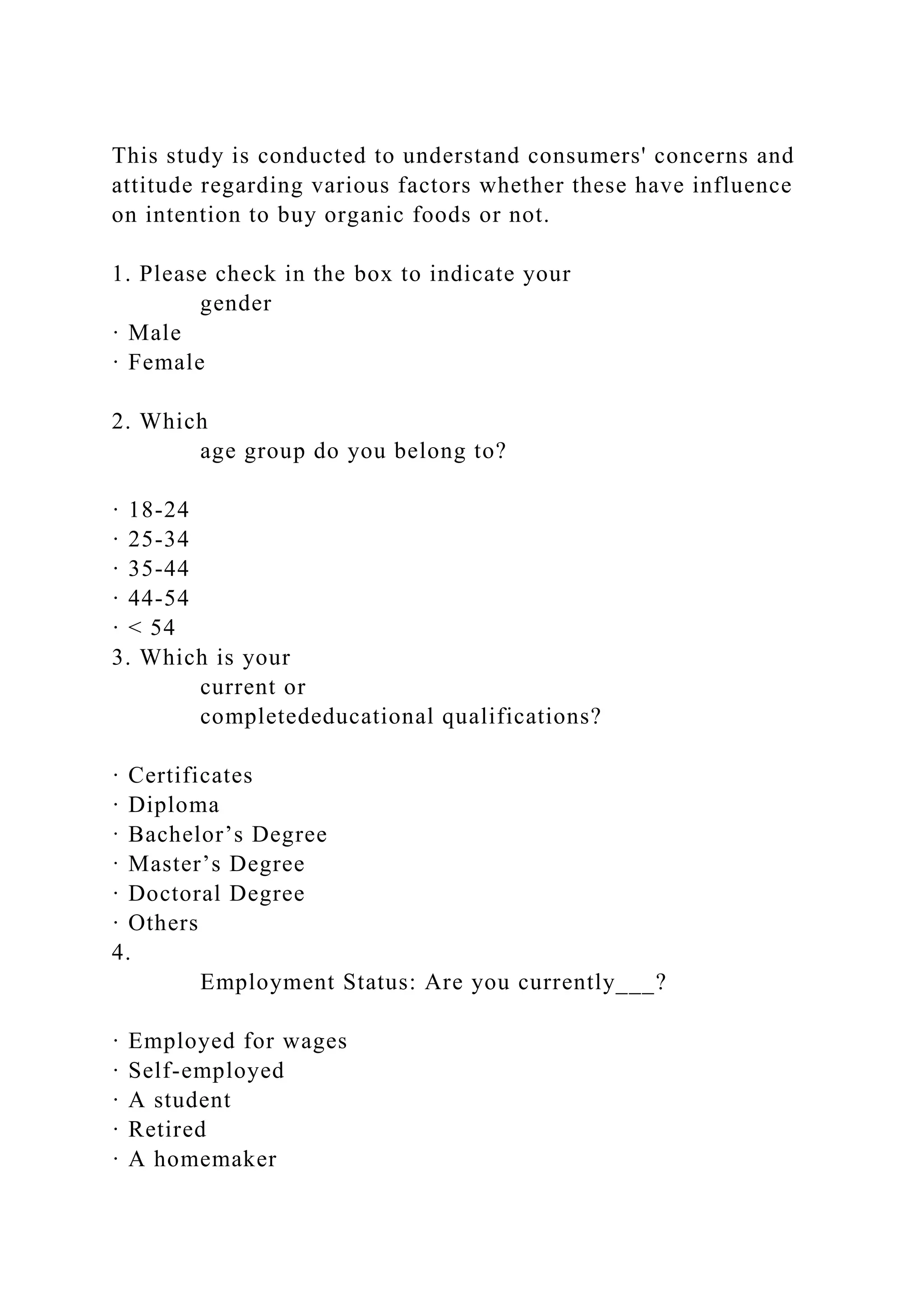

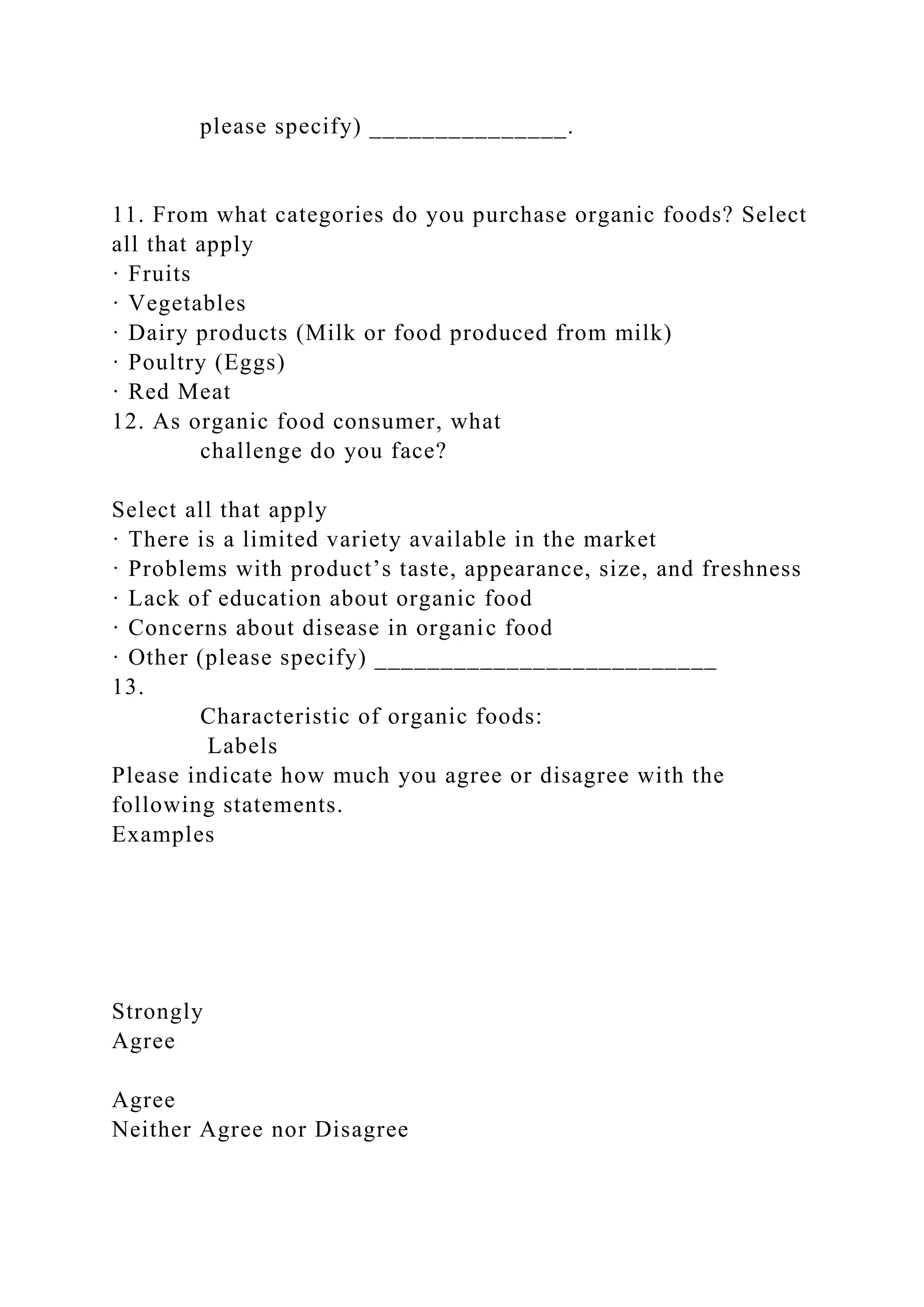

![.232

2.118

.037

Factors

[Environmental concerns]

.161

.085

.271

1.905

.060

Factors [Food safety]

-.008

.084

-.014

-.099

.921

Factors [Price]

-.106

.057

-.190

-1.869

.065

Factors [Better animal welfare]

.072

.073

.133

.988

.326

H1: Health consciousness is the most influential factor which

affect consumer purchase intention.

a. Dependent Variable: SumPurchase](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/submittedinpartfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof-230119024927-31555ff9/75/Submitted-in-part-fulfilment-of-the-requirements-for-the-degree-of-docx-83-2048.jpg)

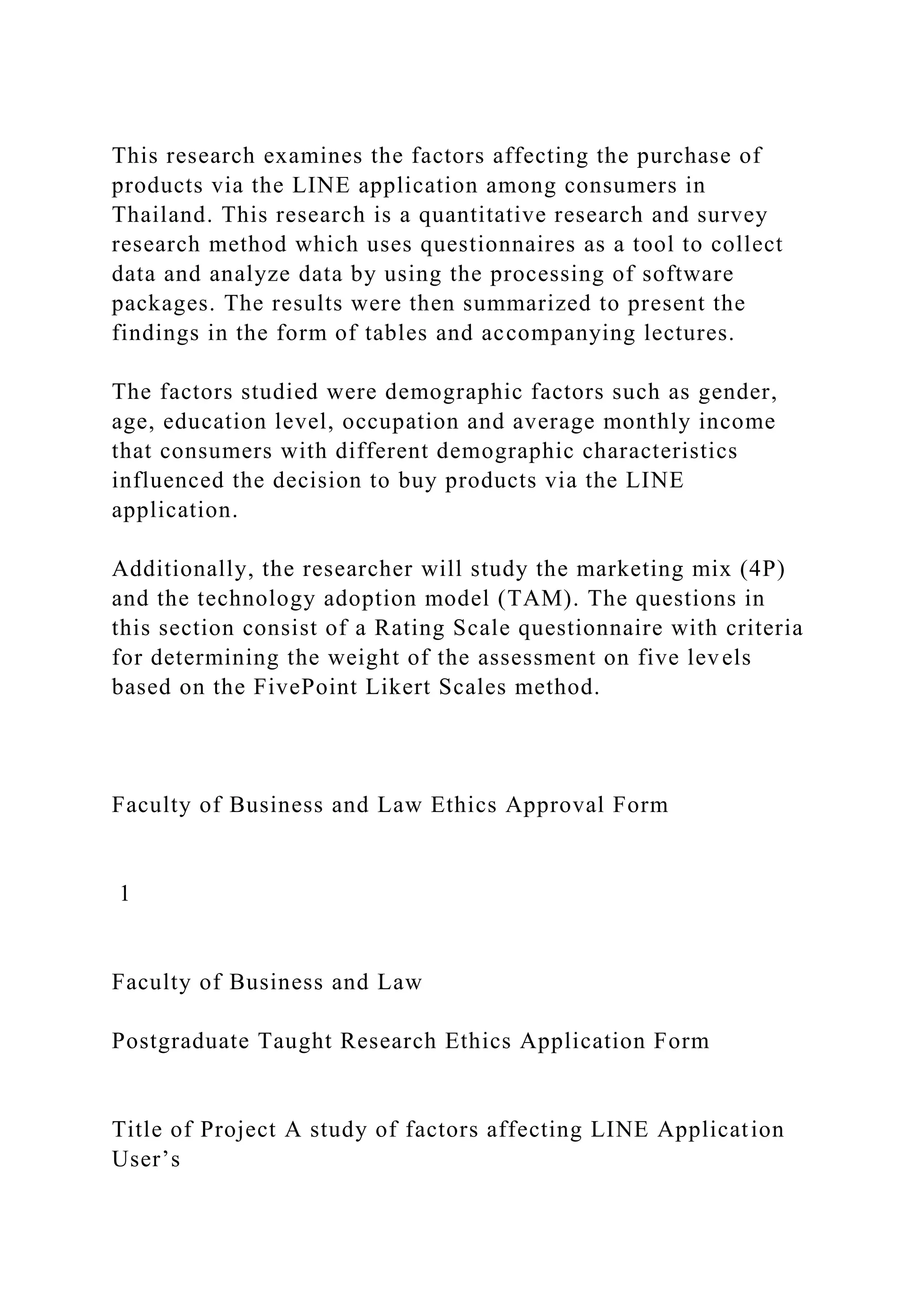

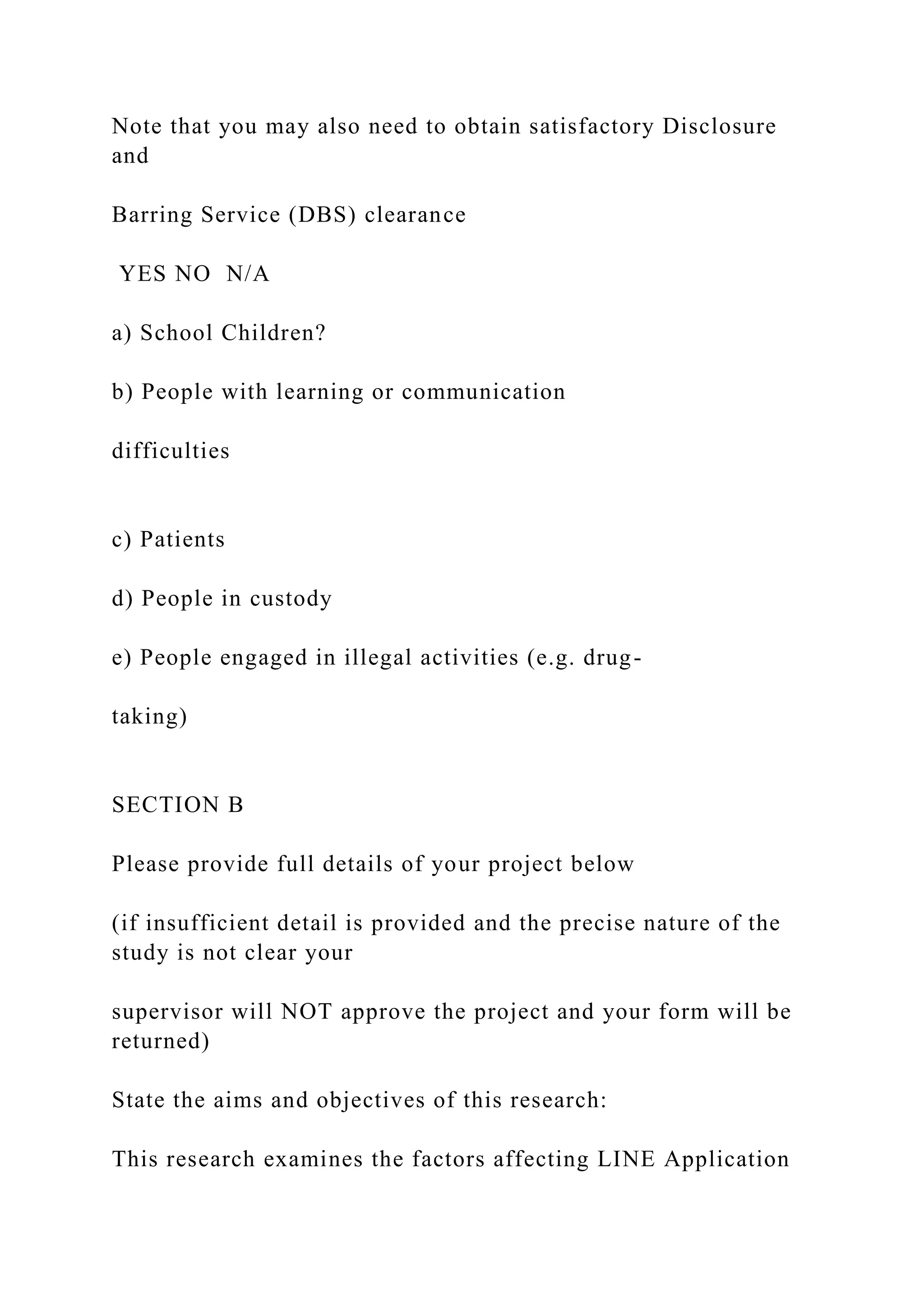

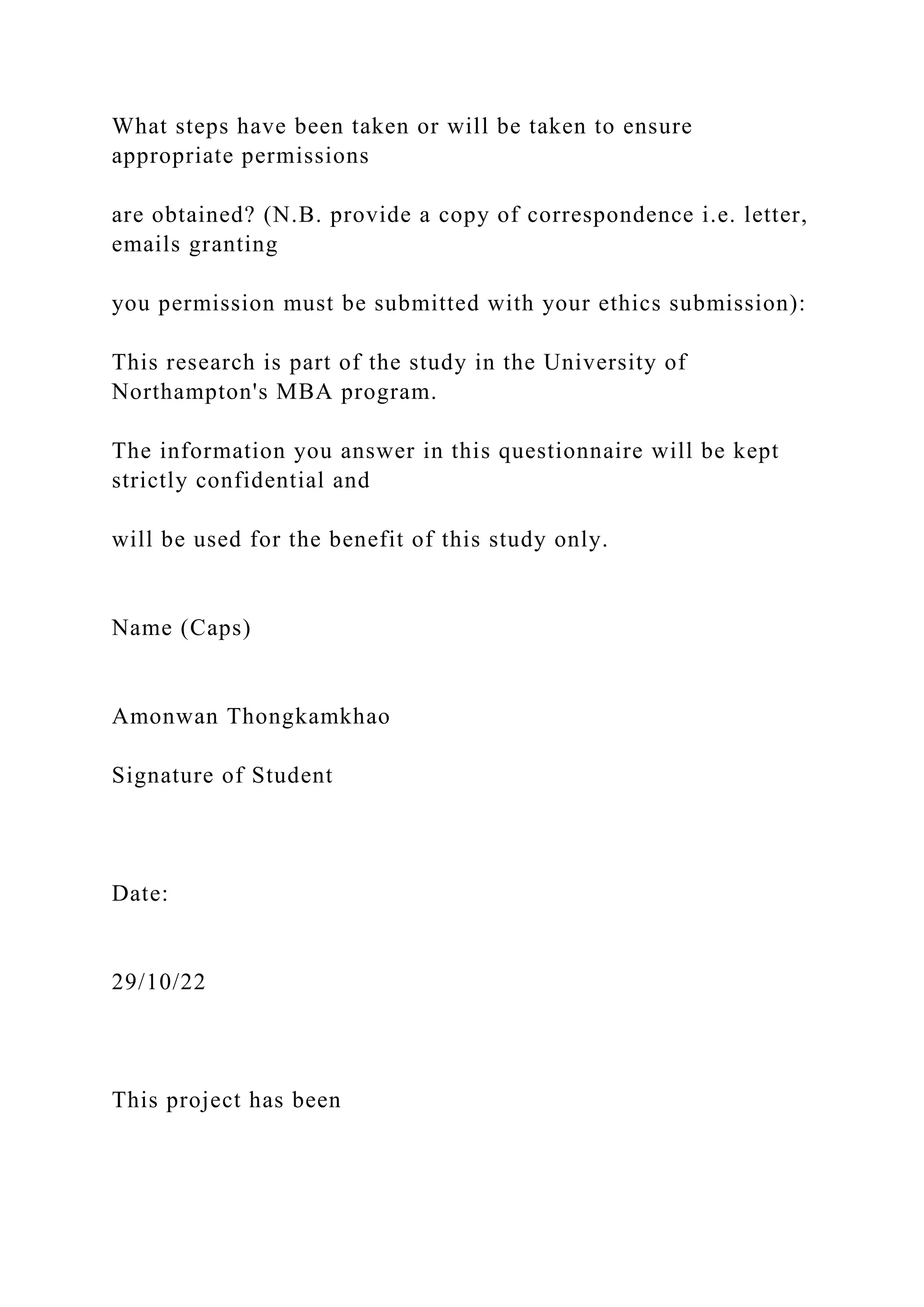

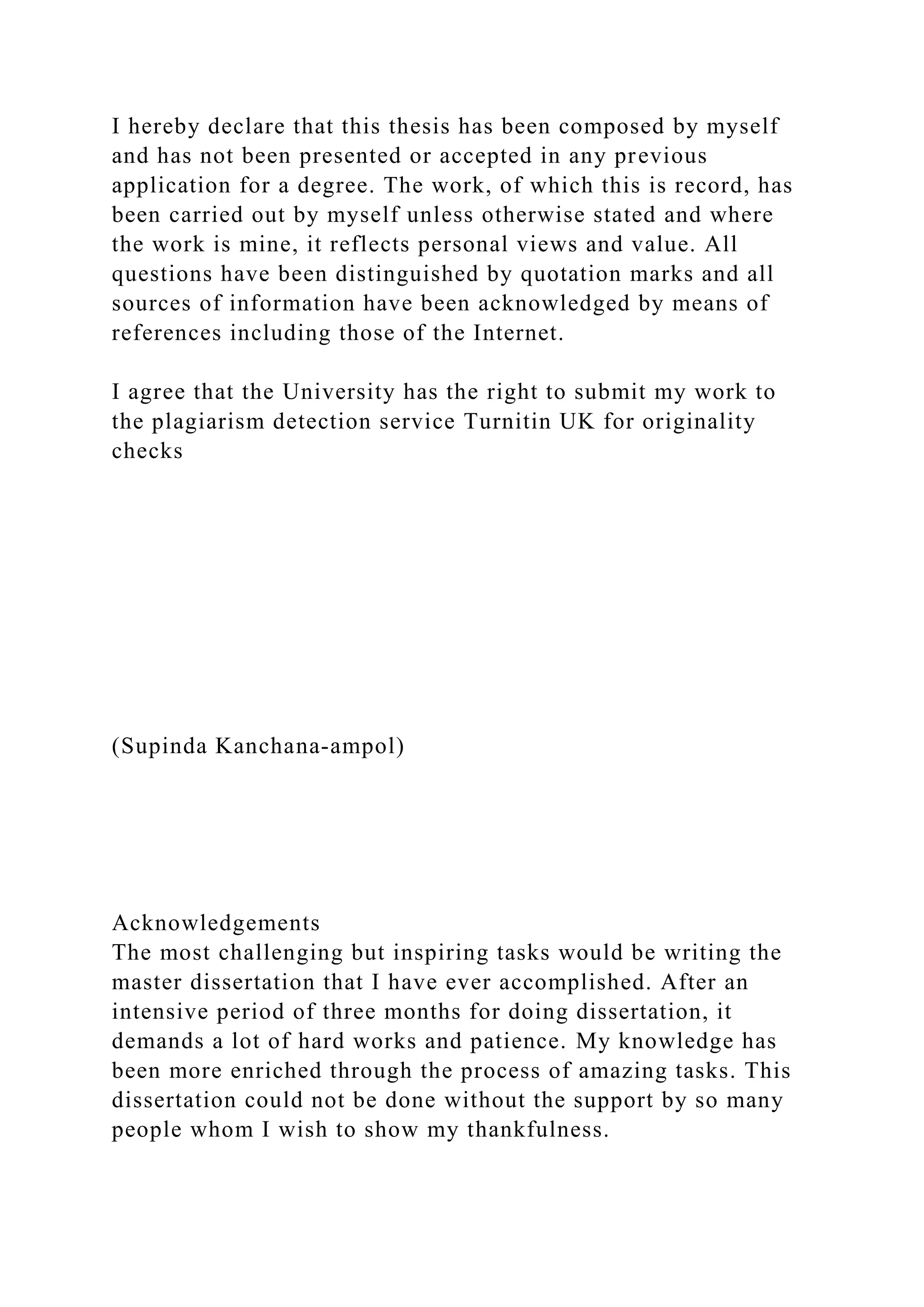

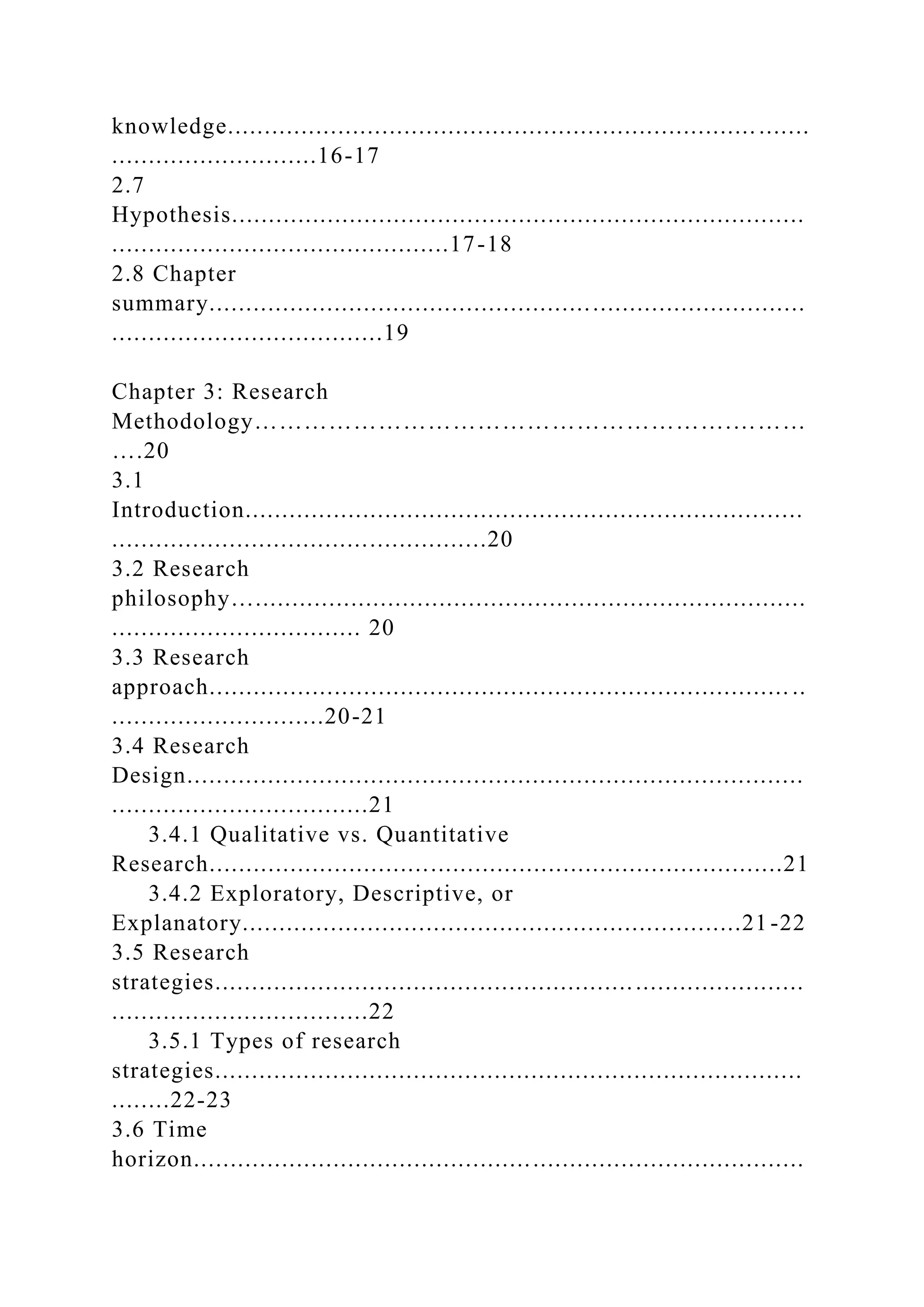

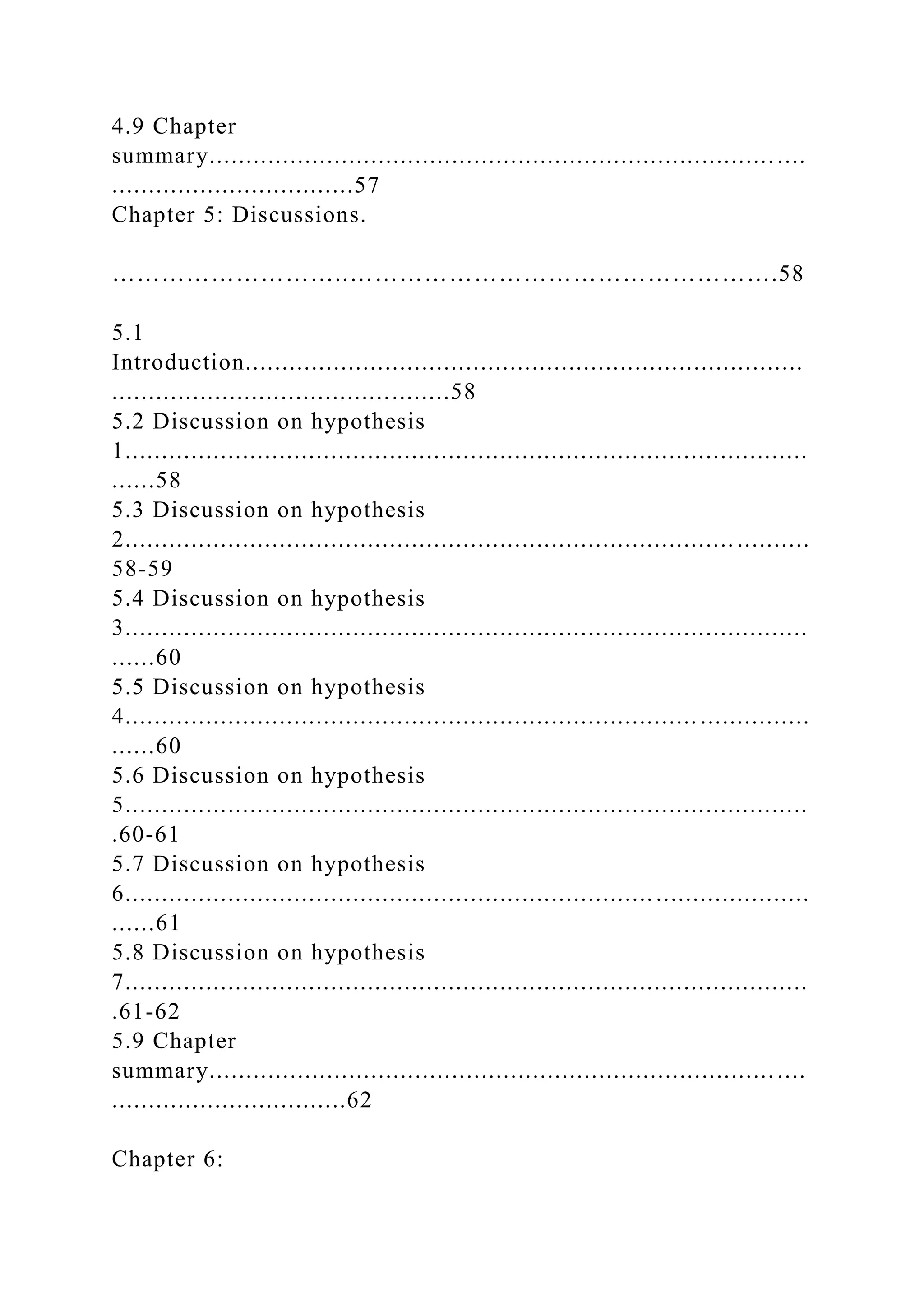

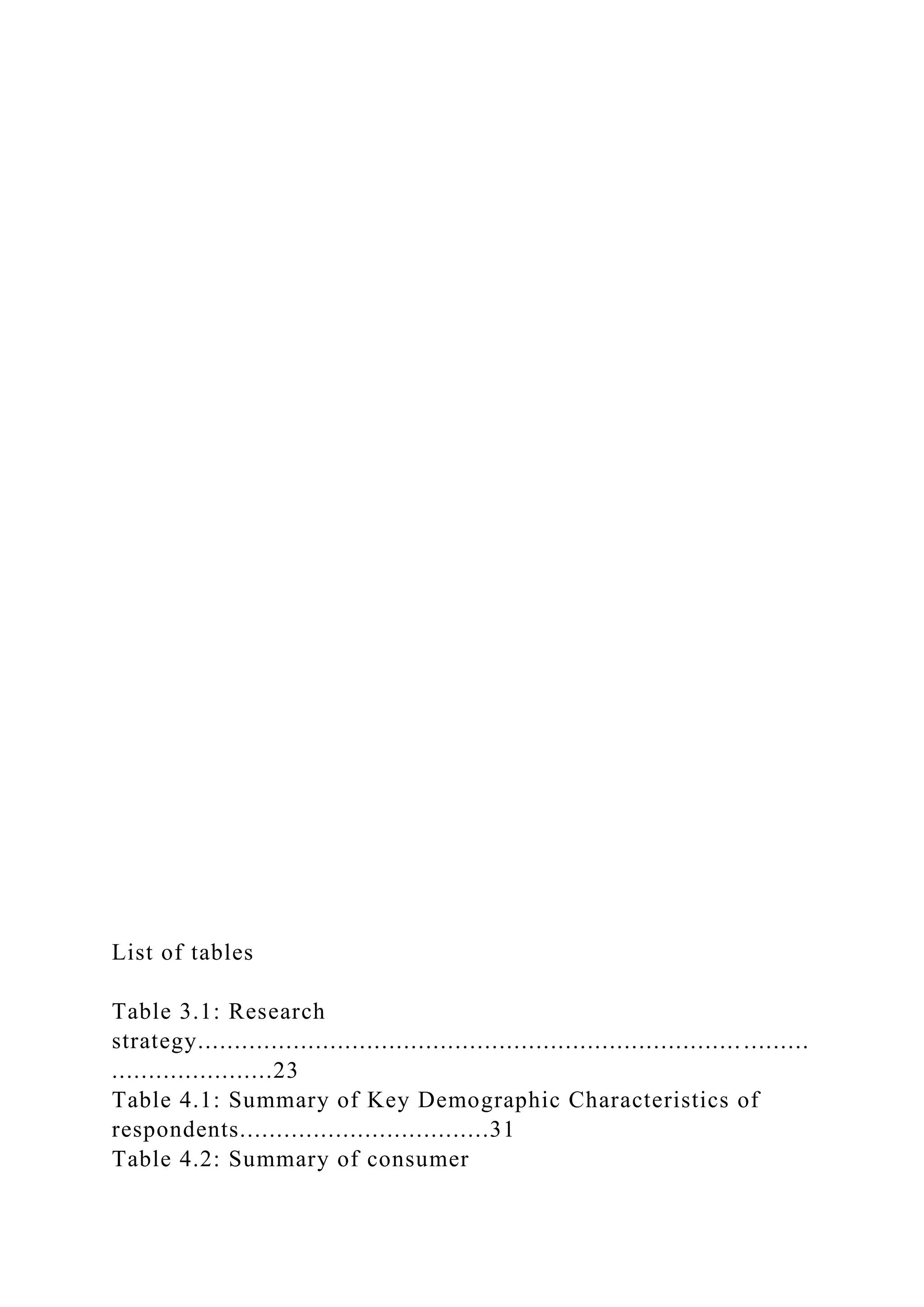

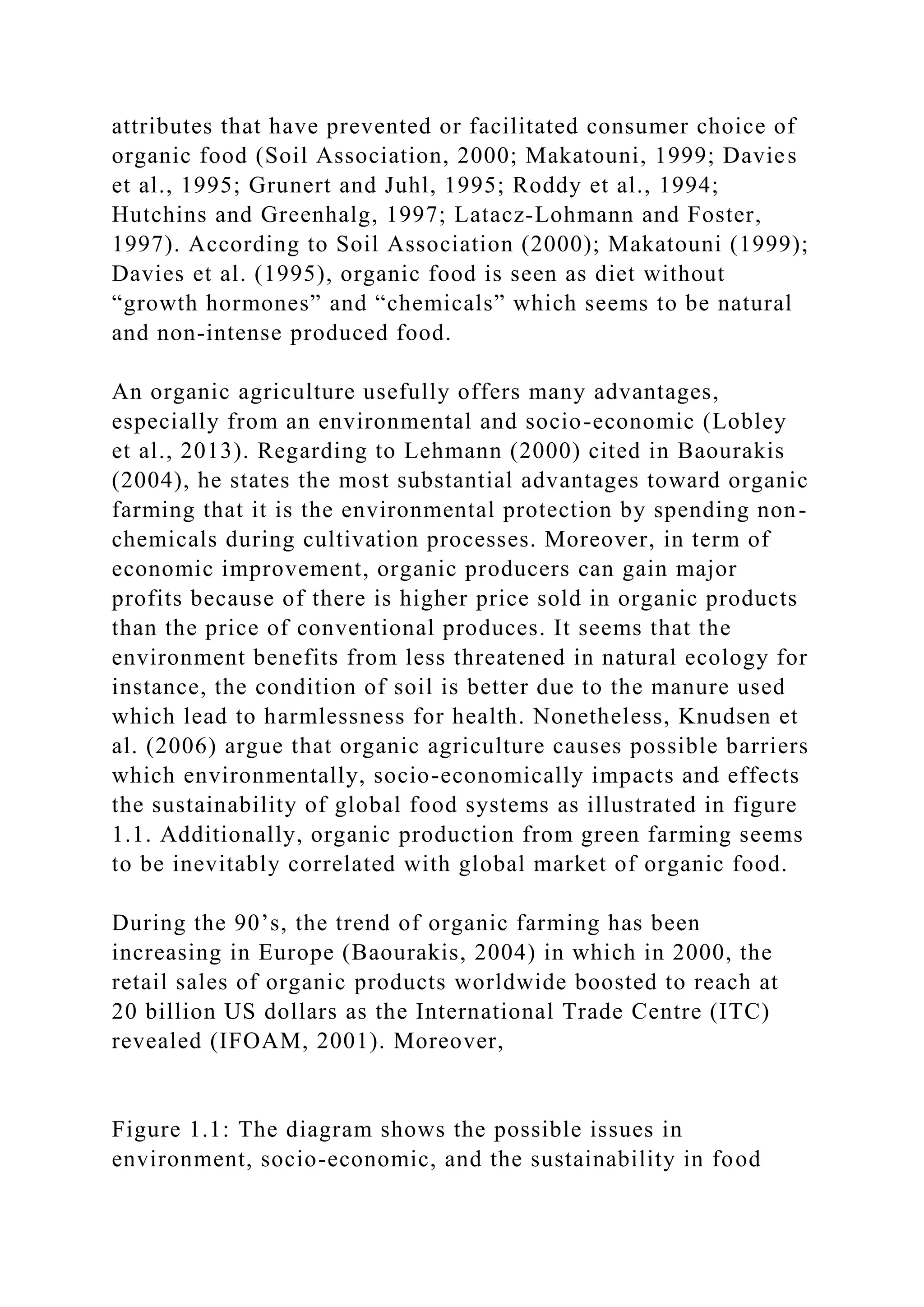

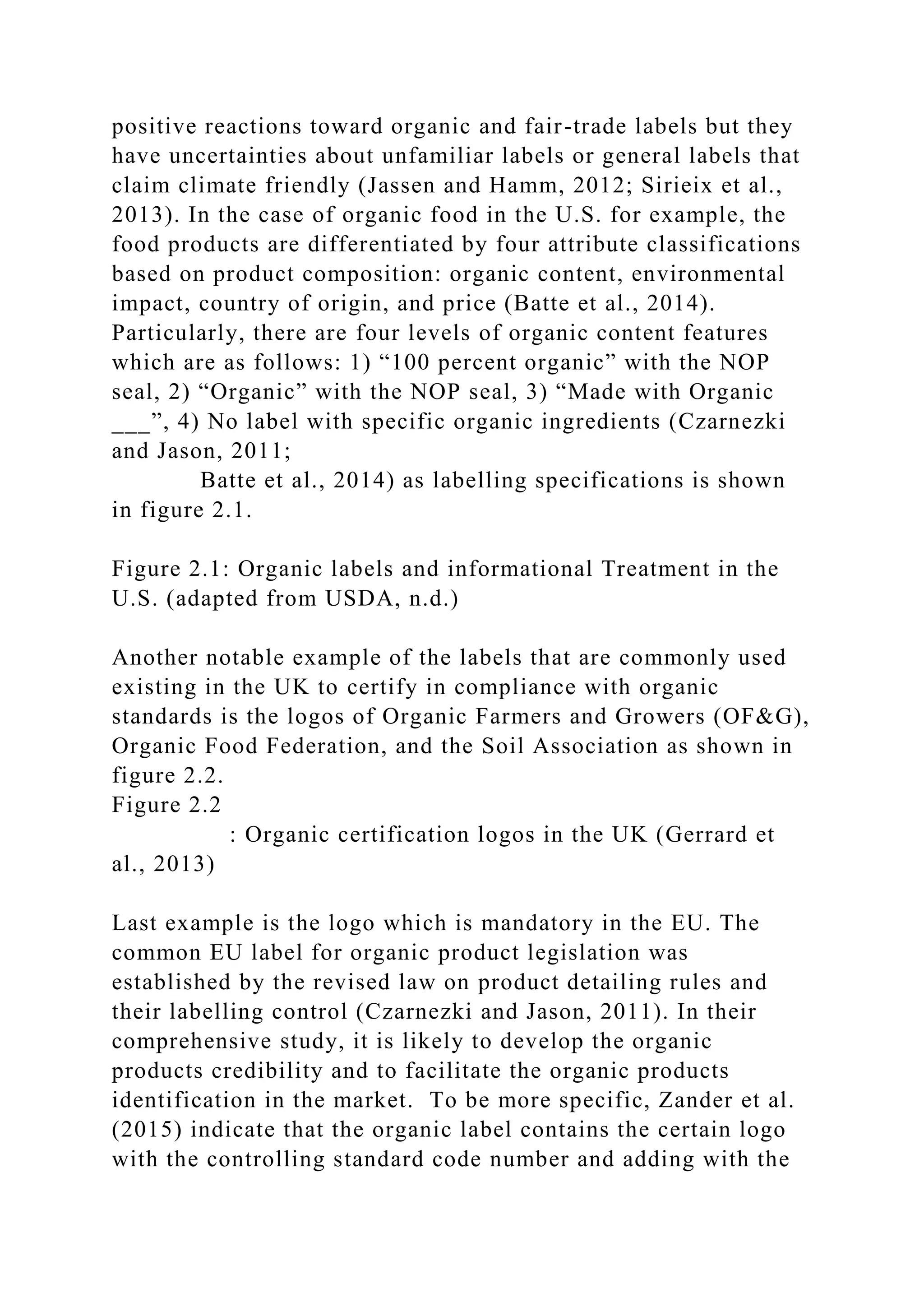

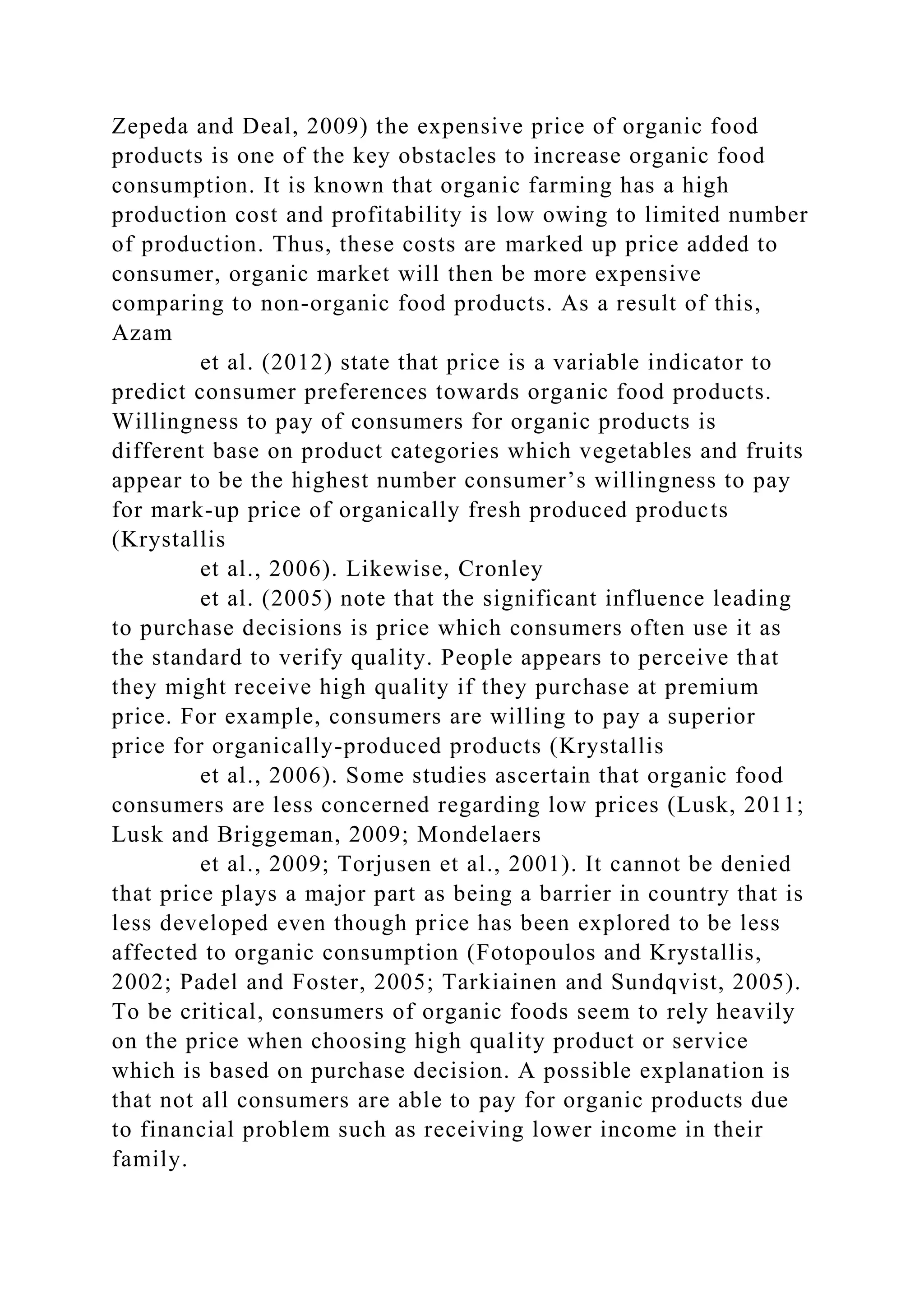

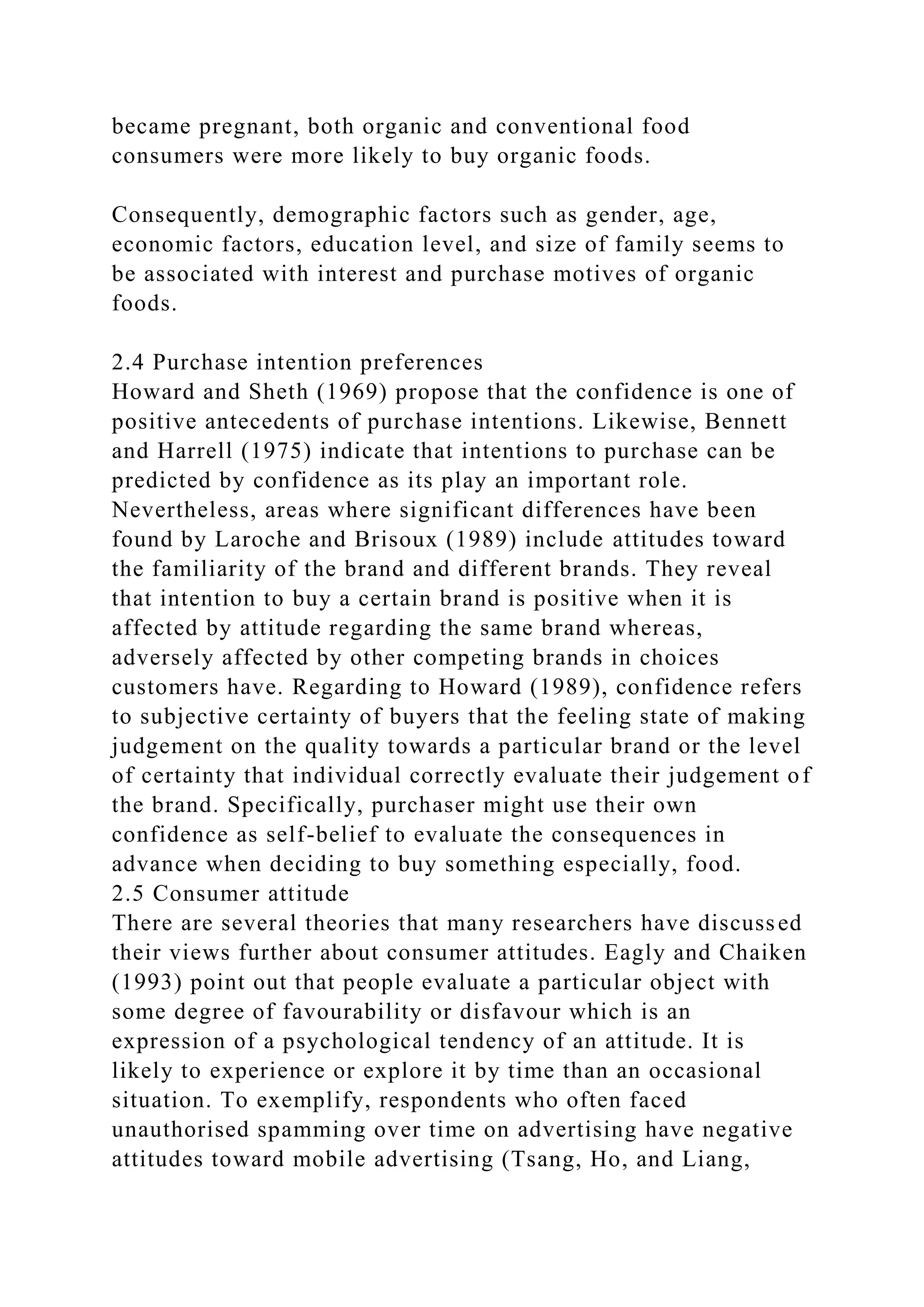

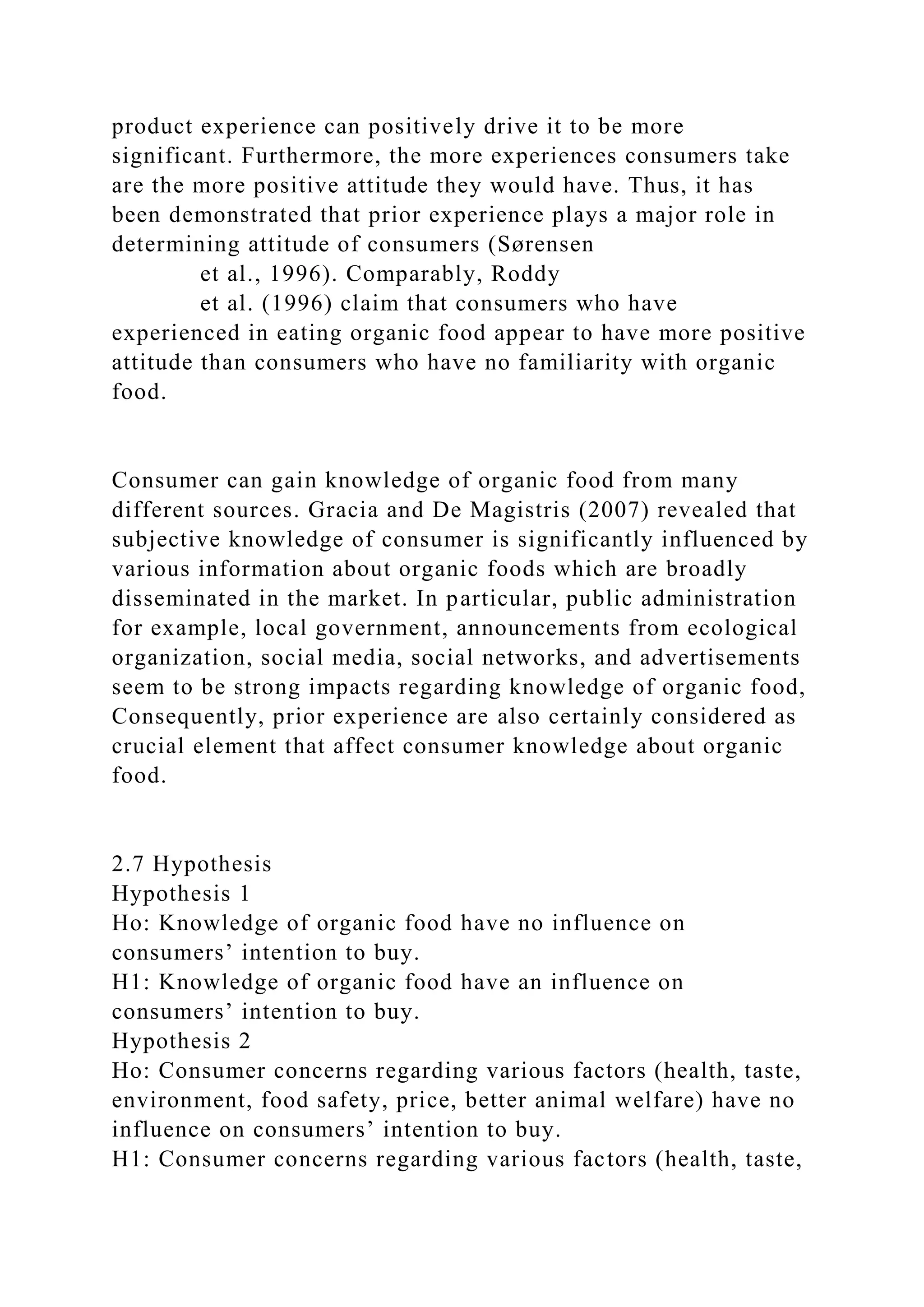

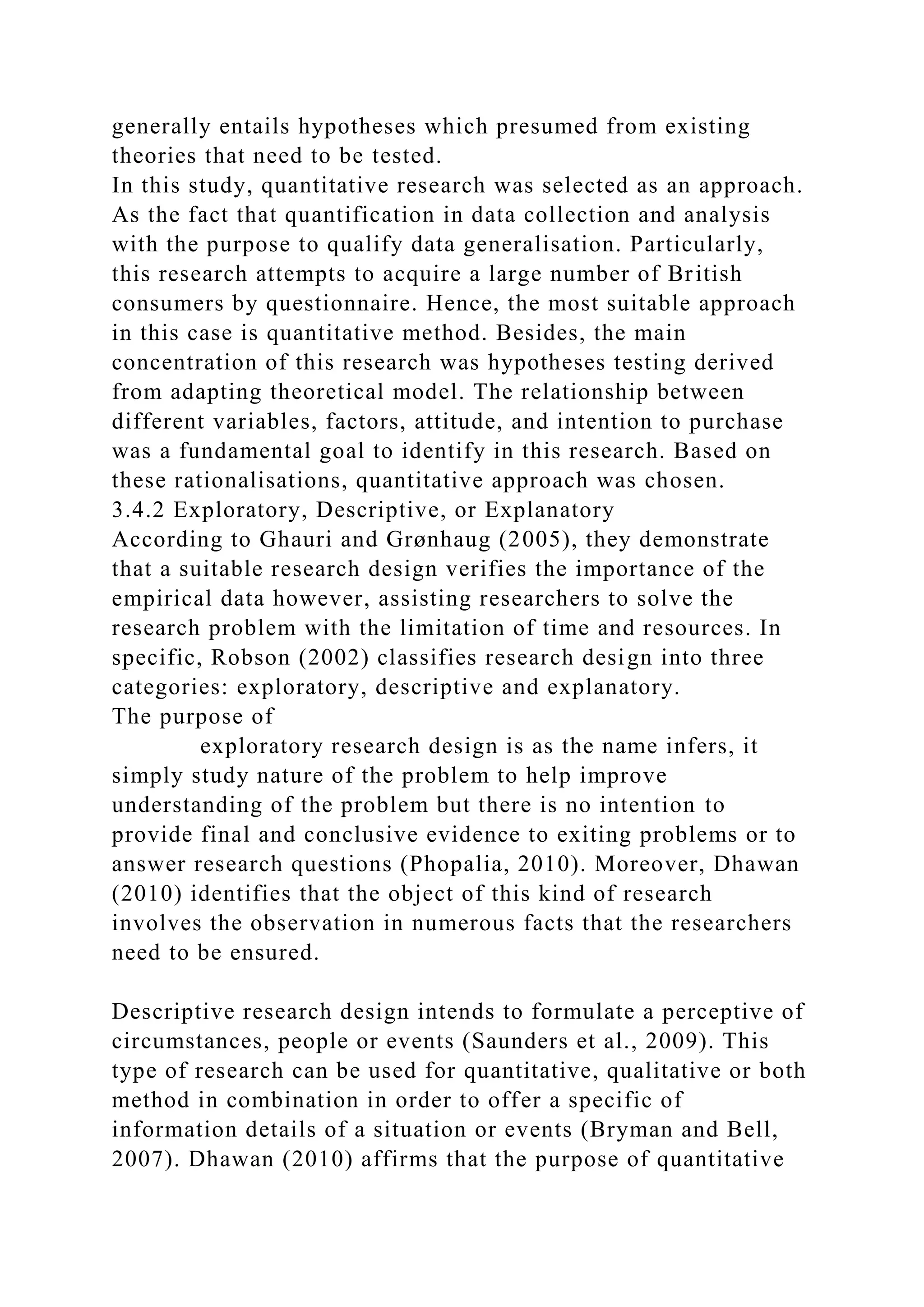

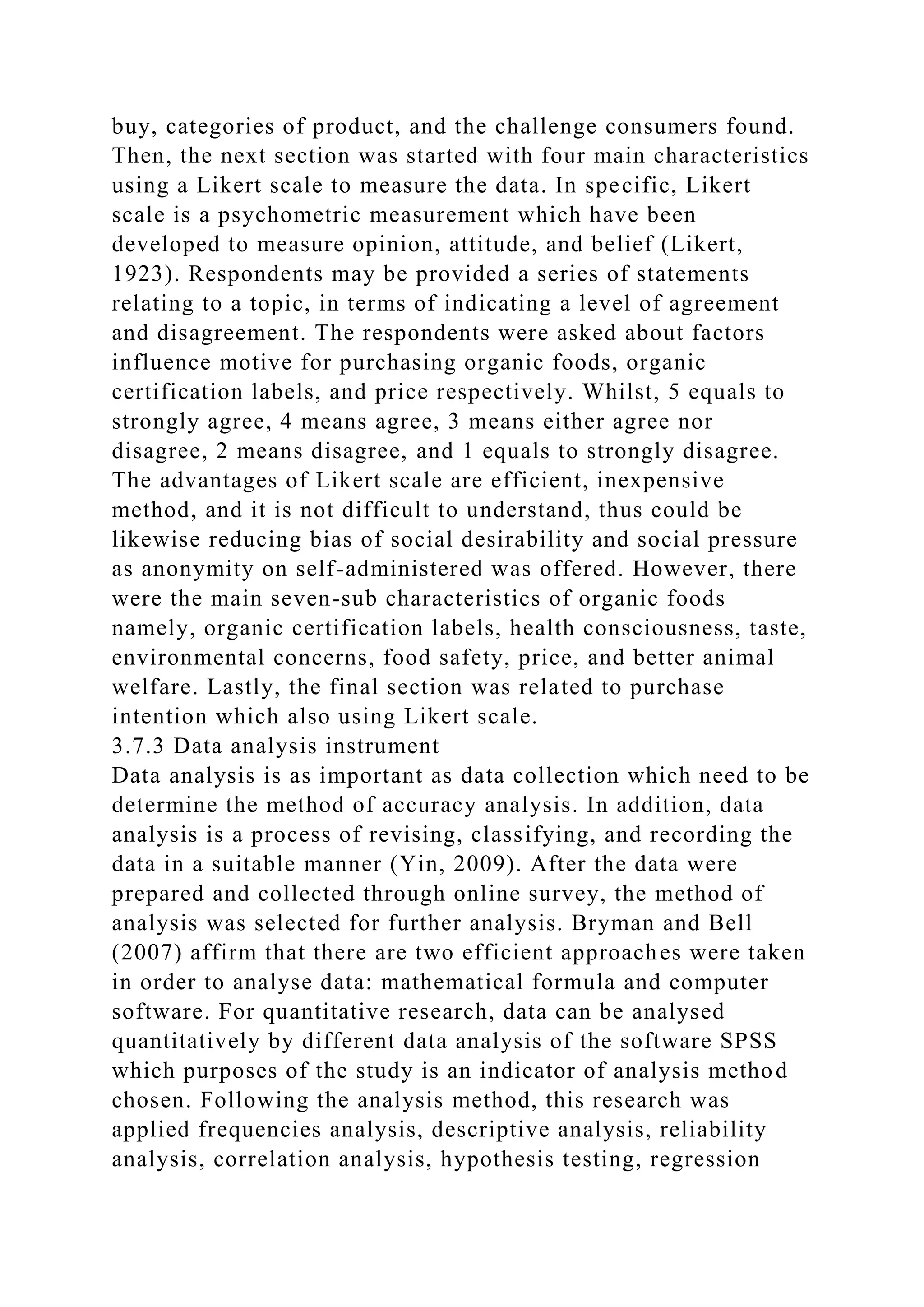

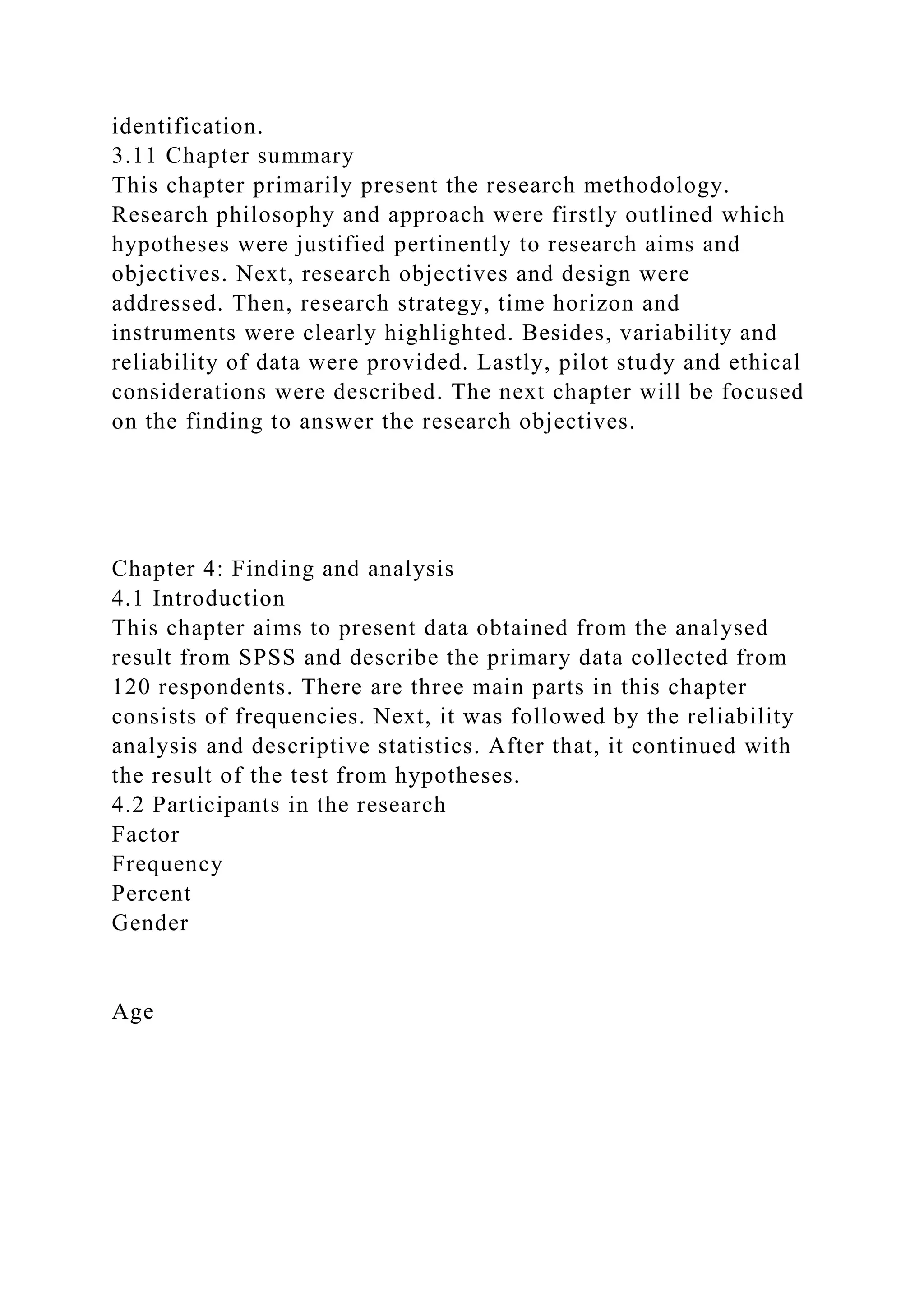

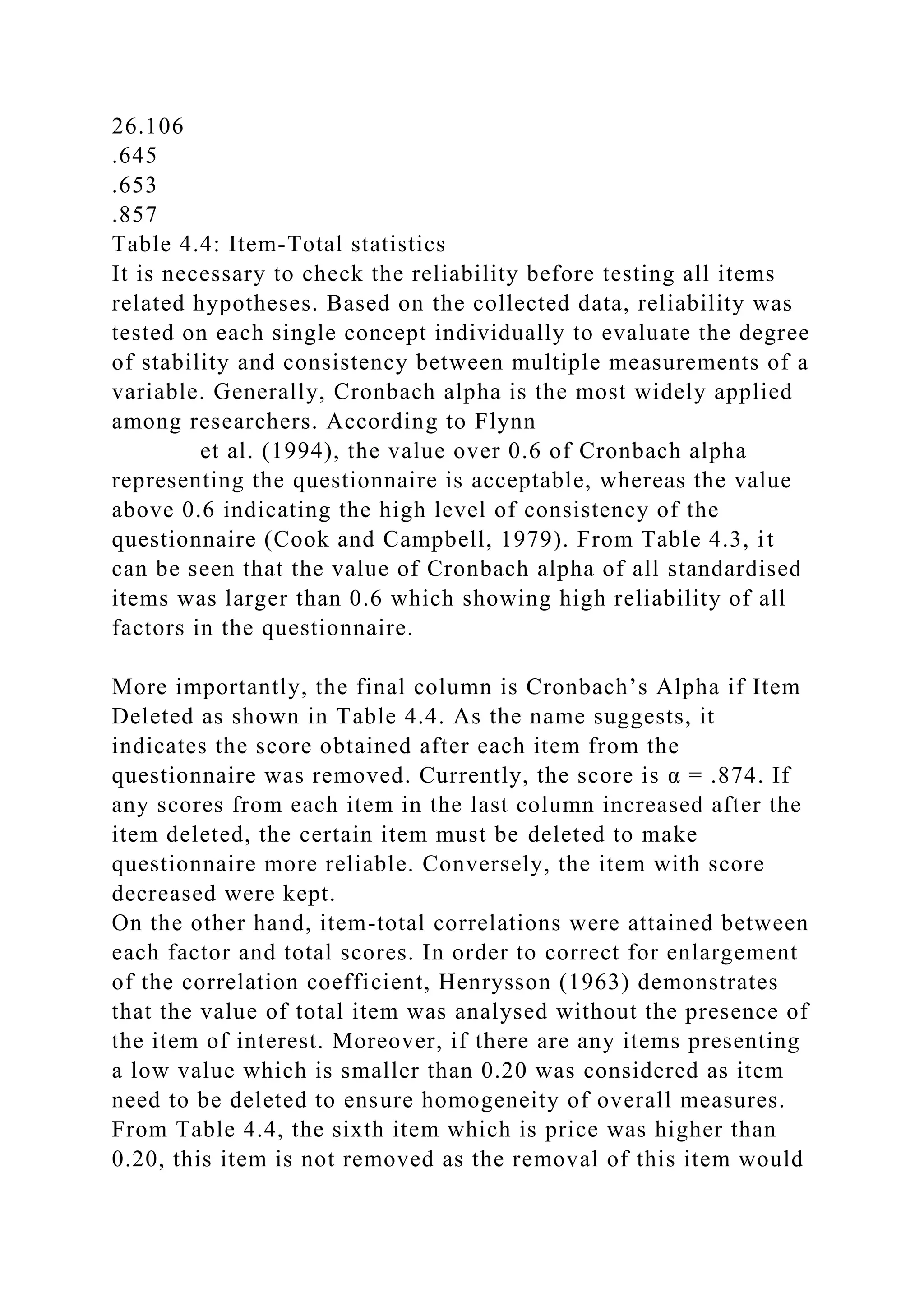

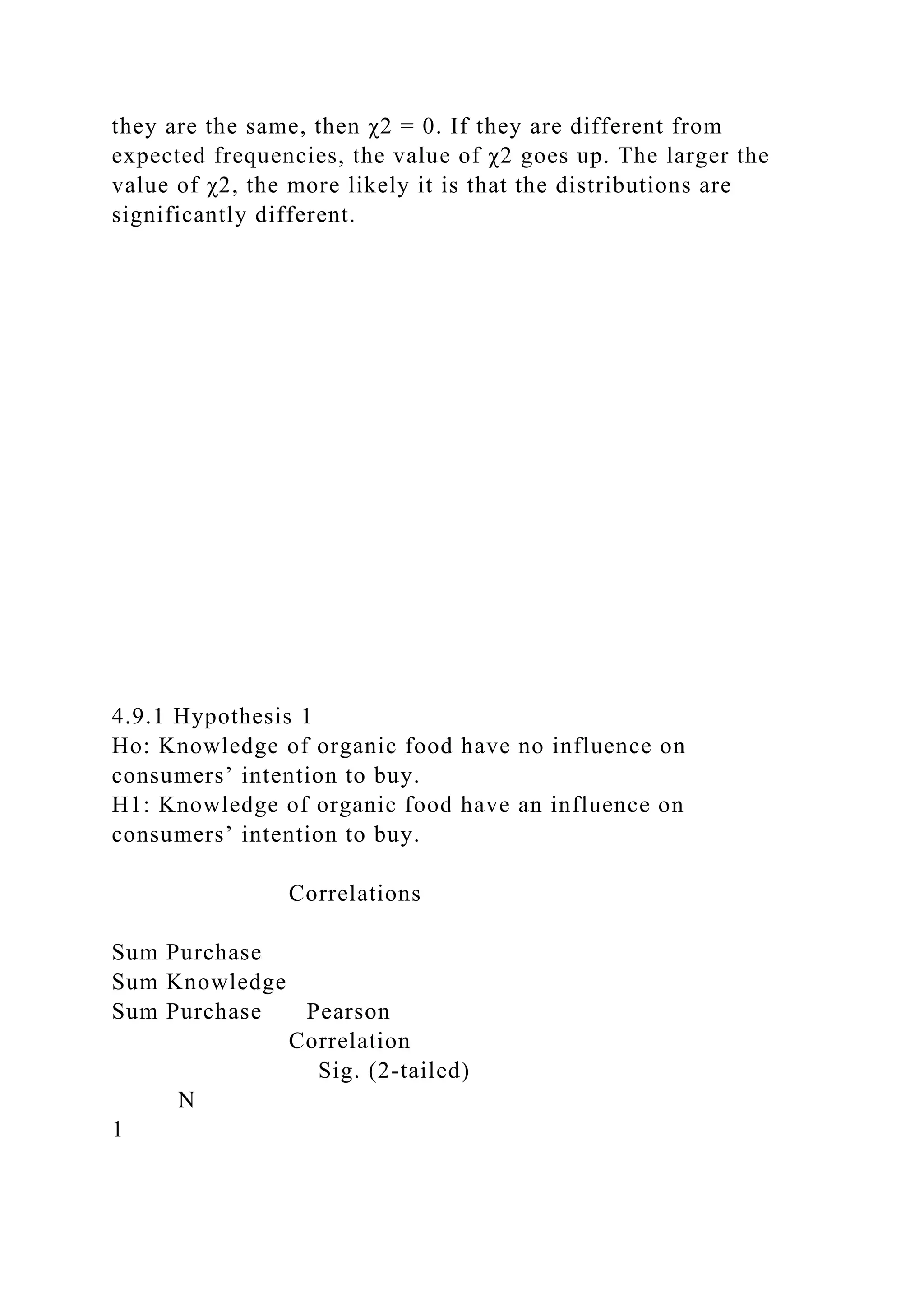

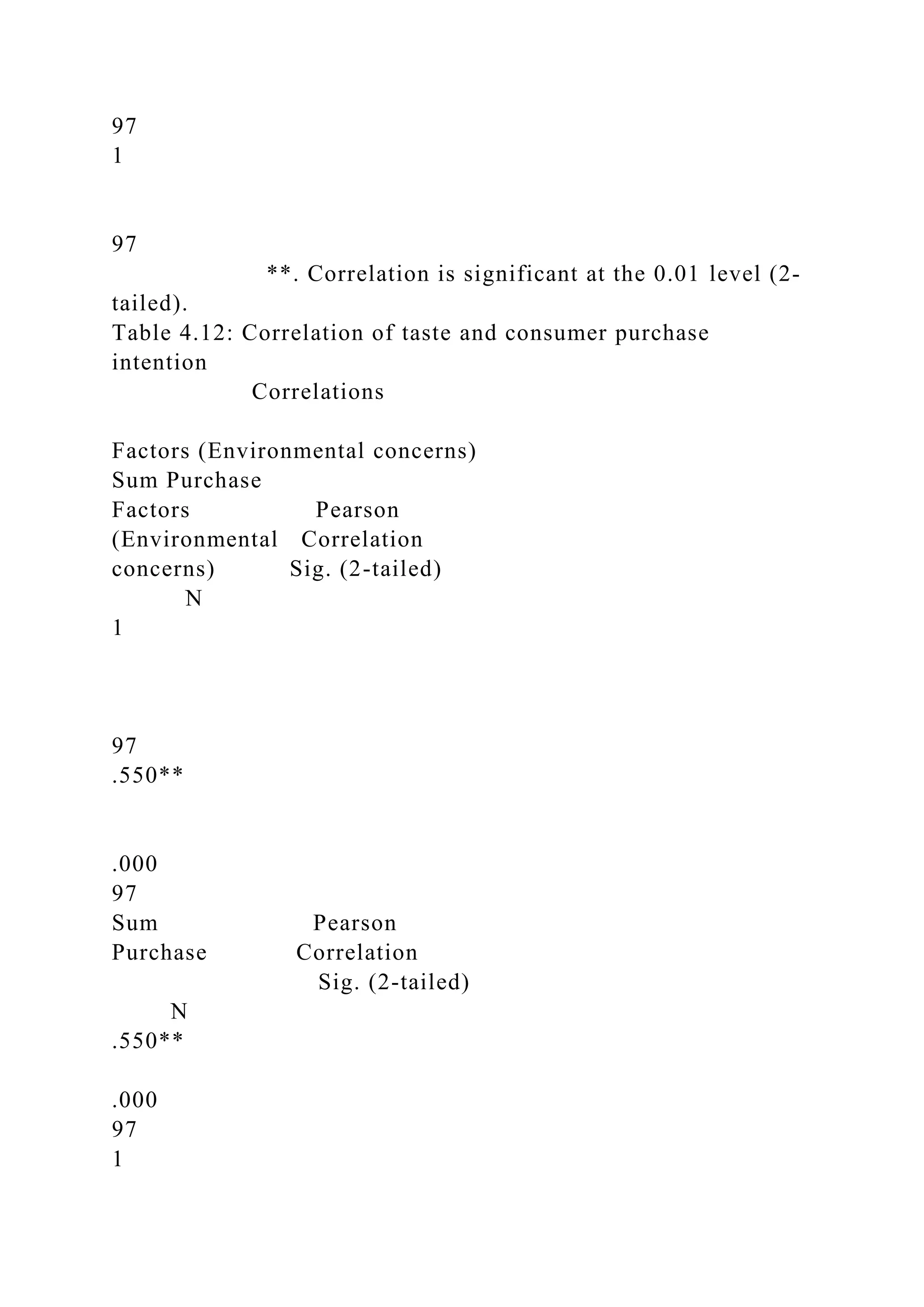

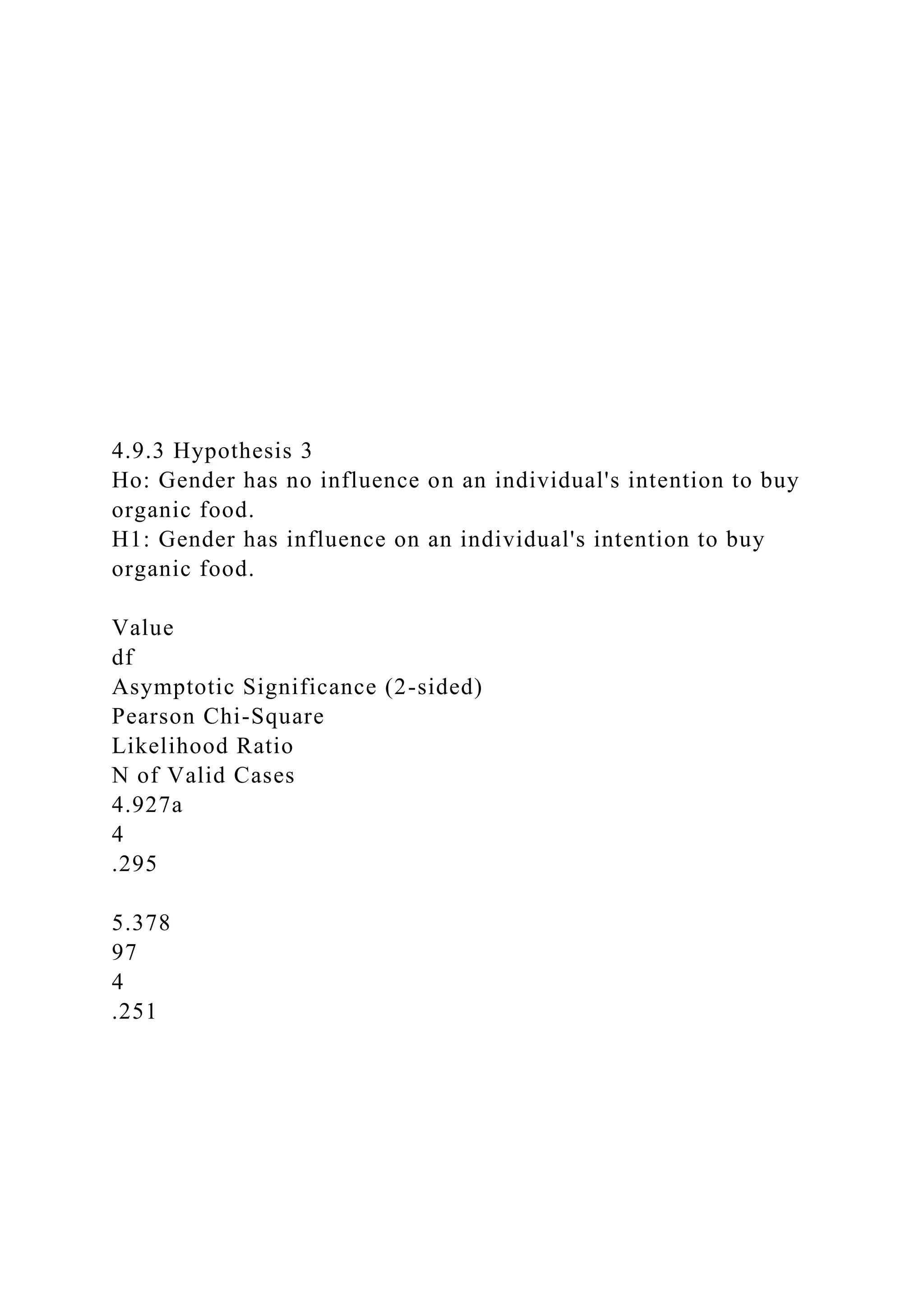

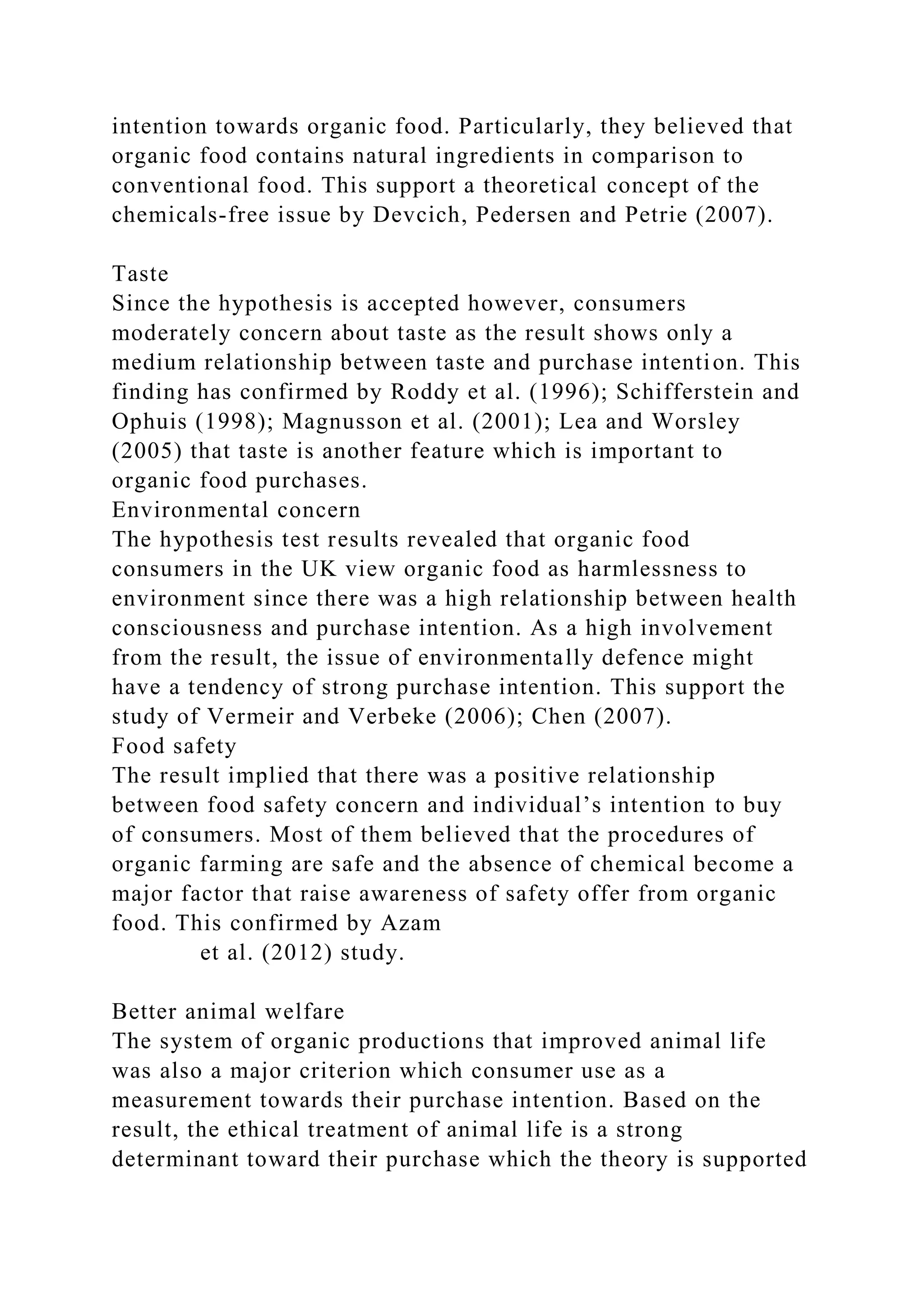

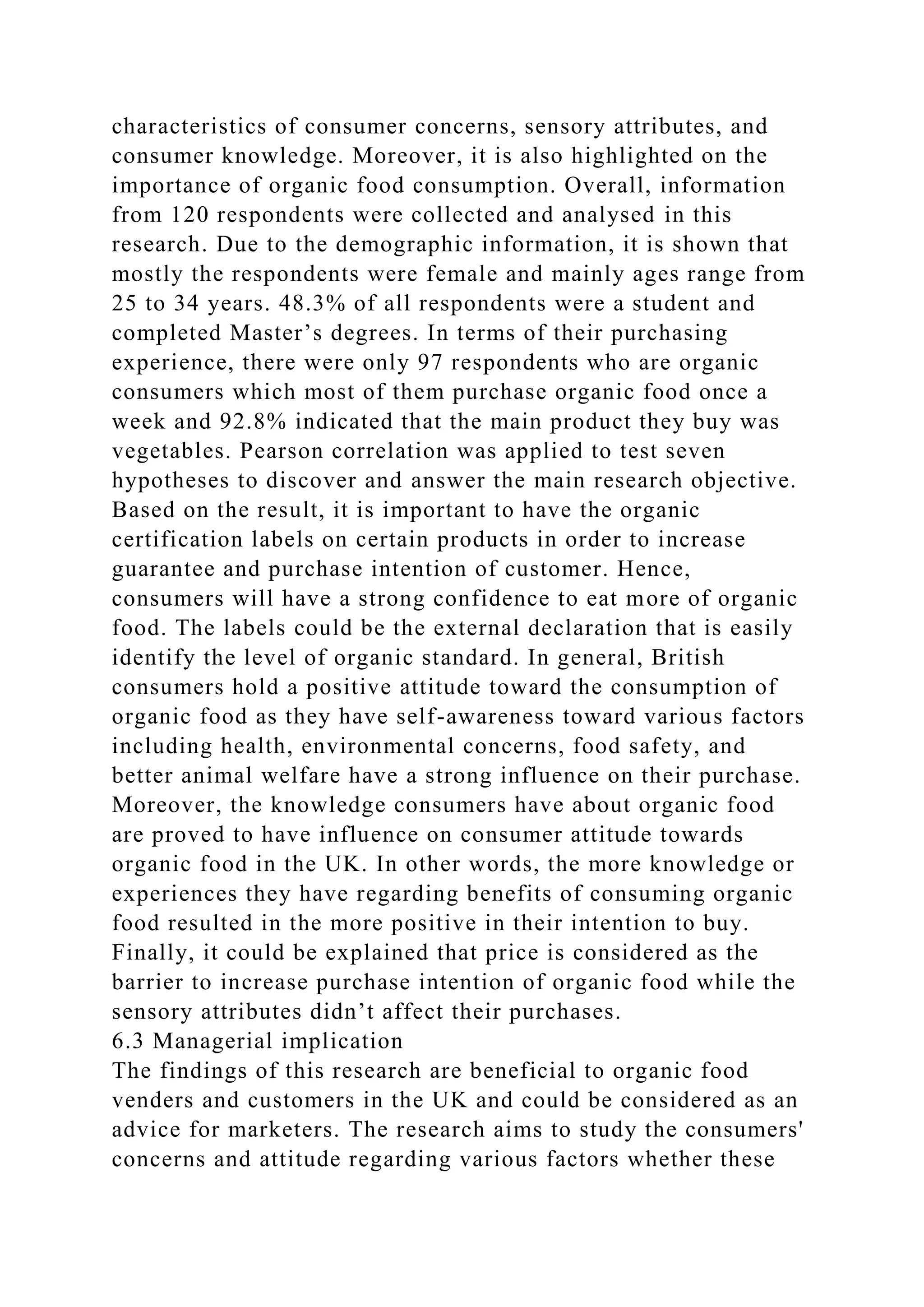

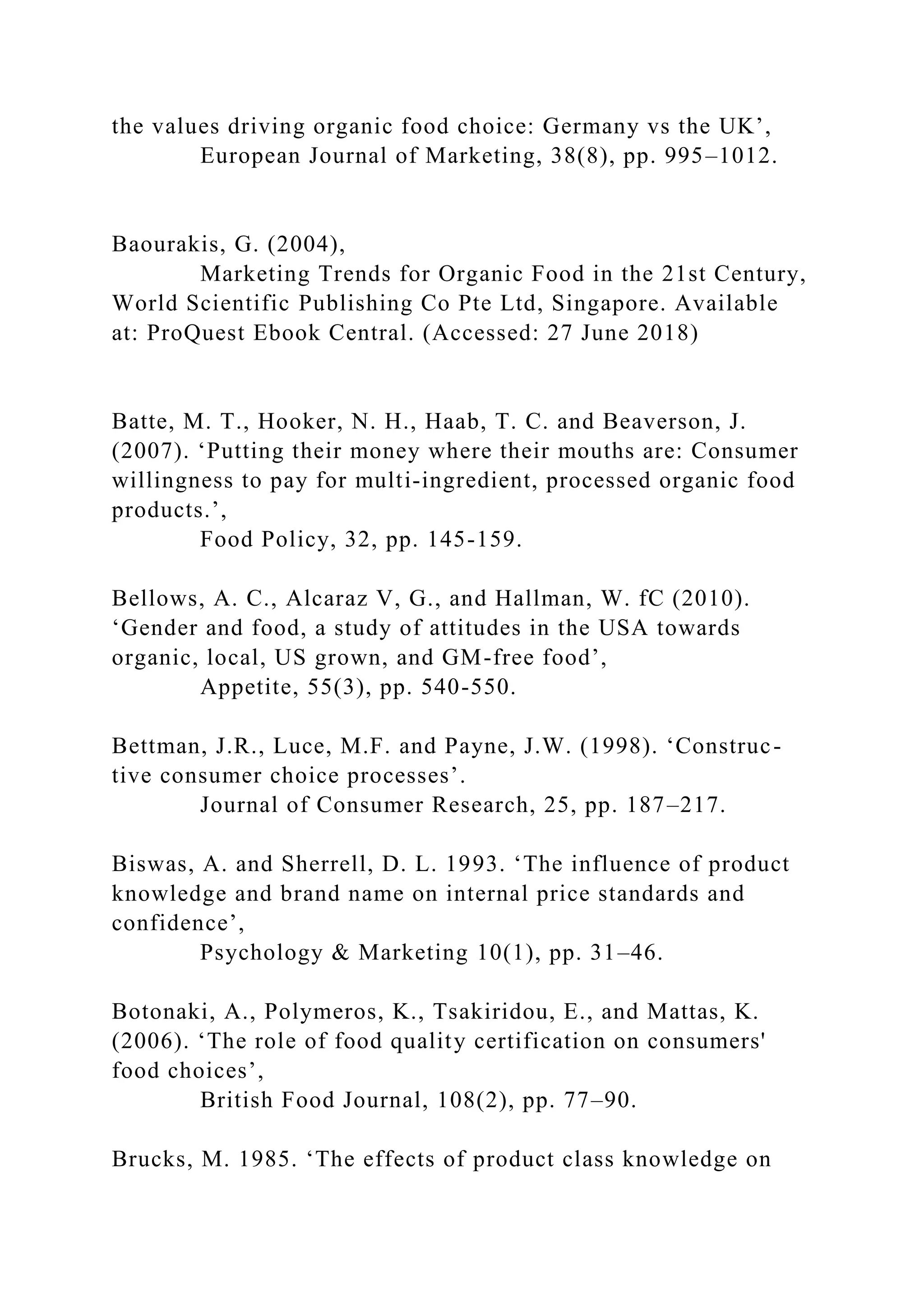

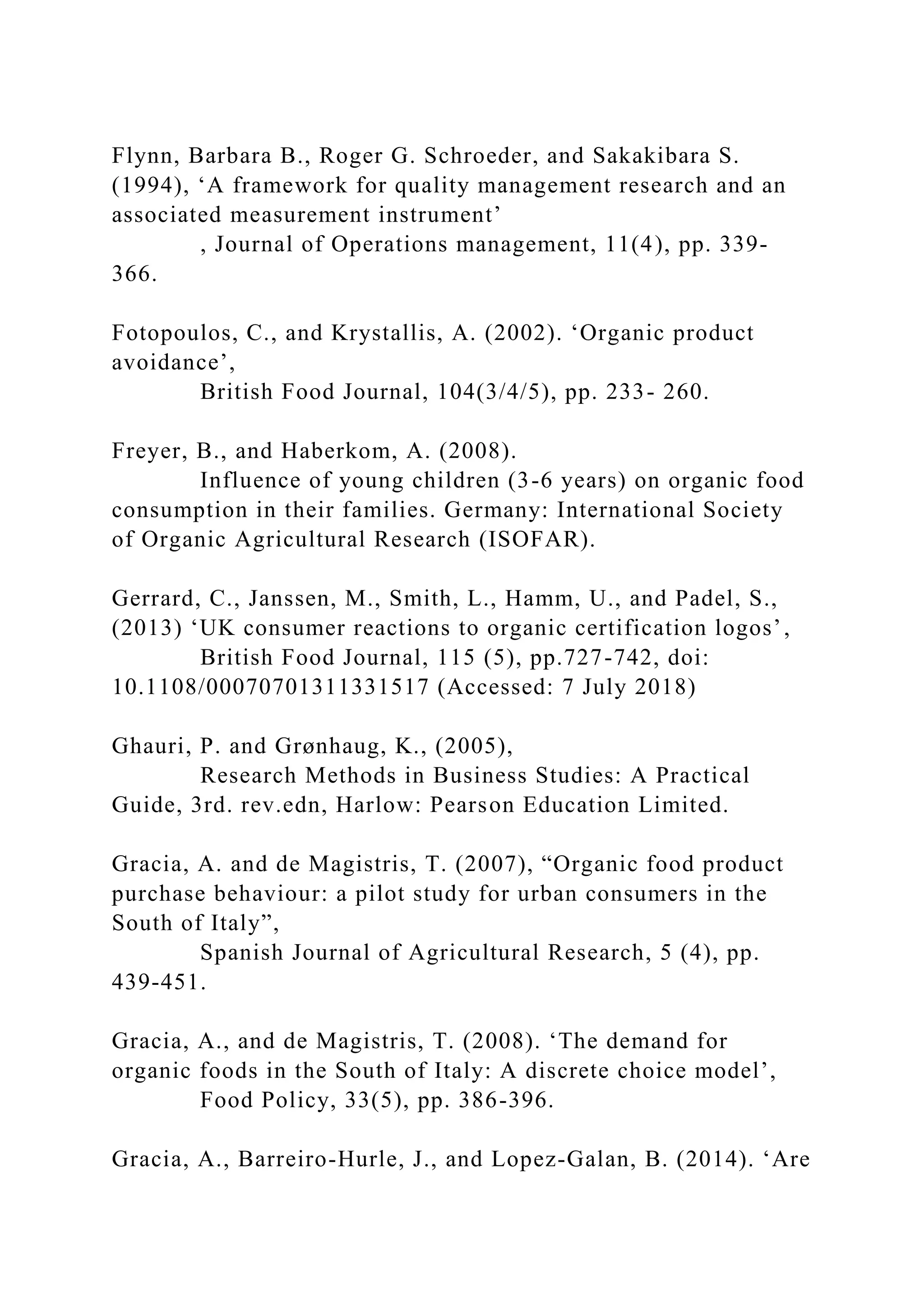

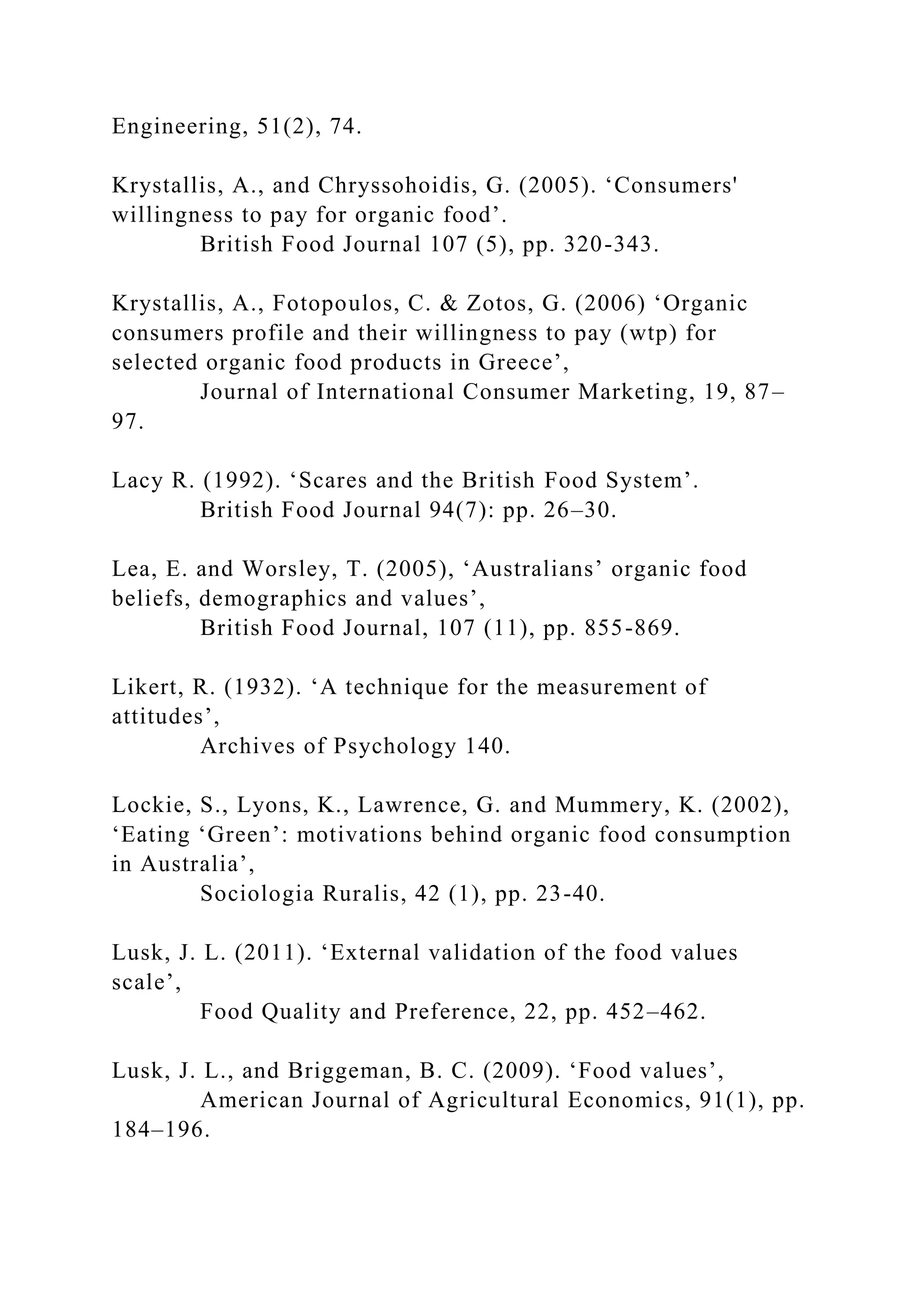

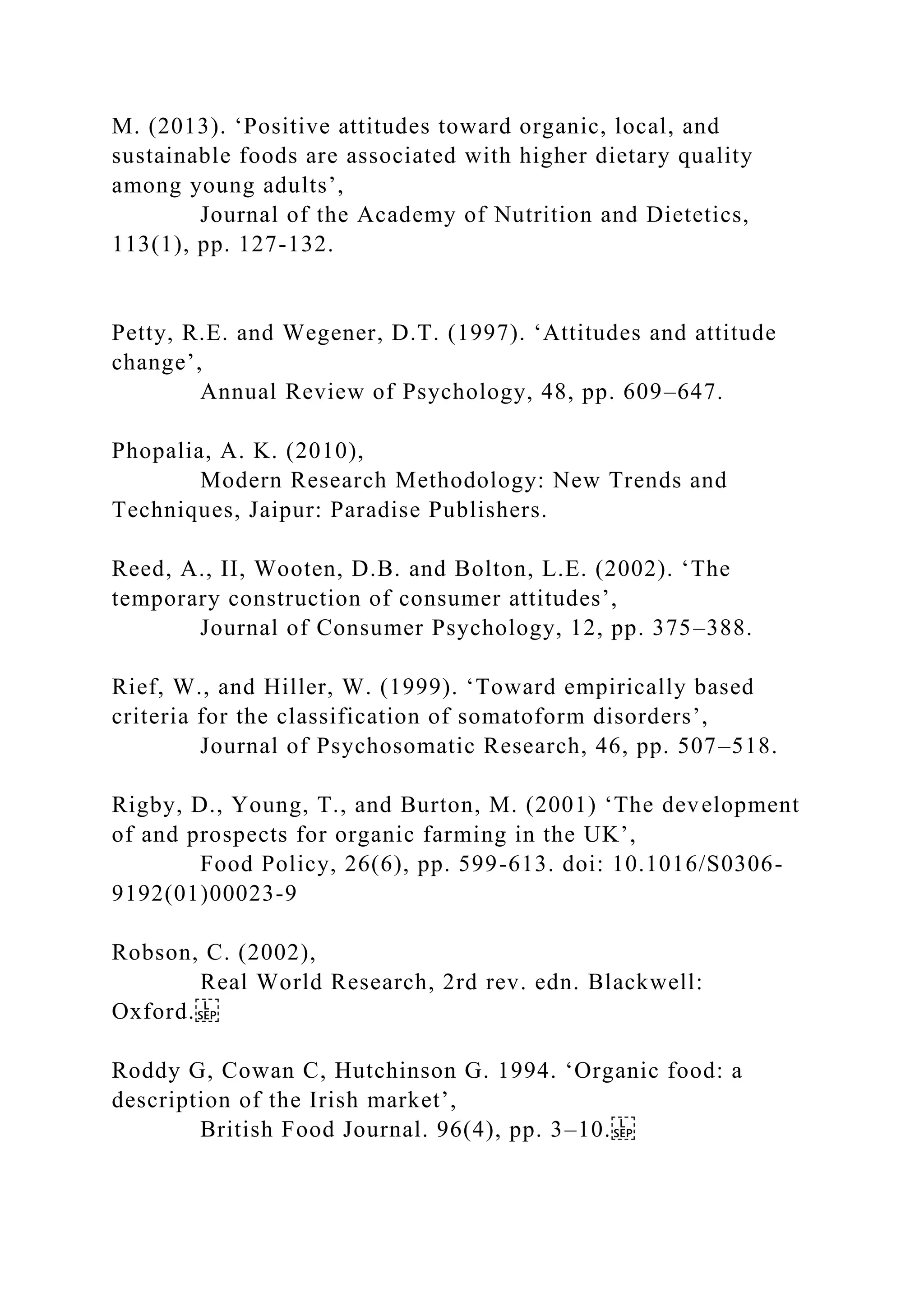

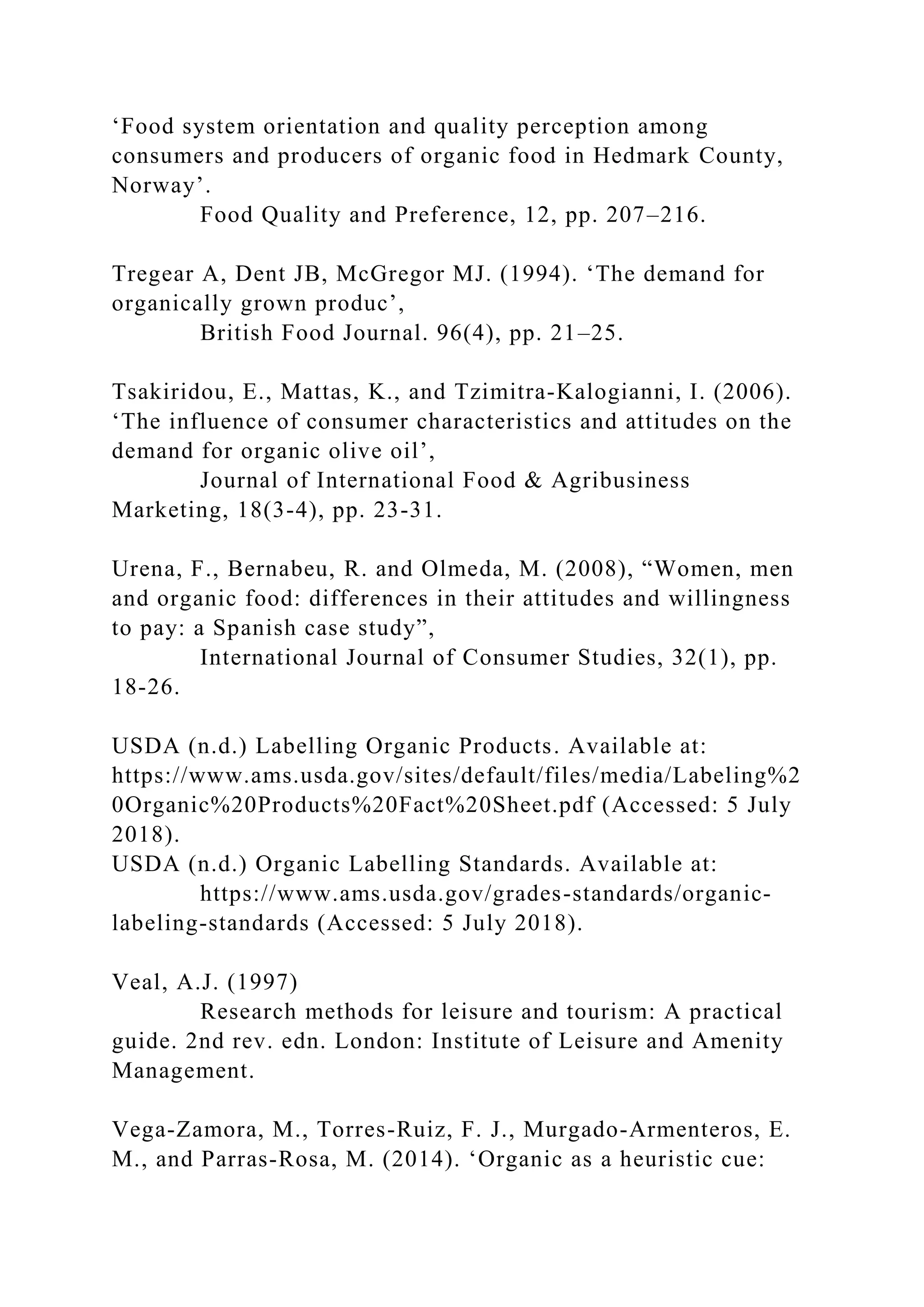

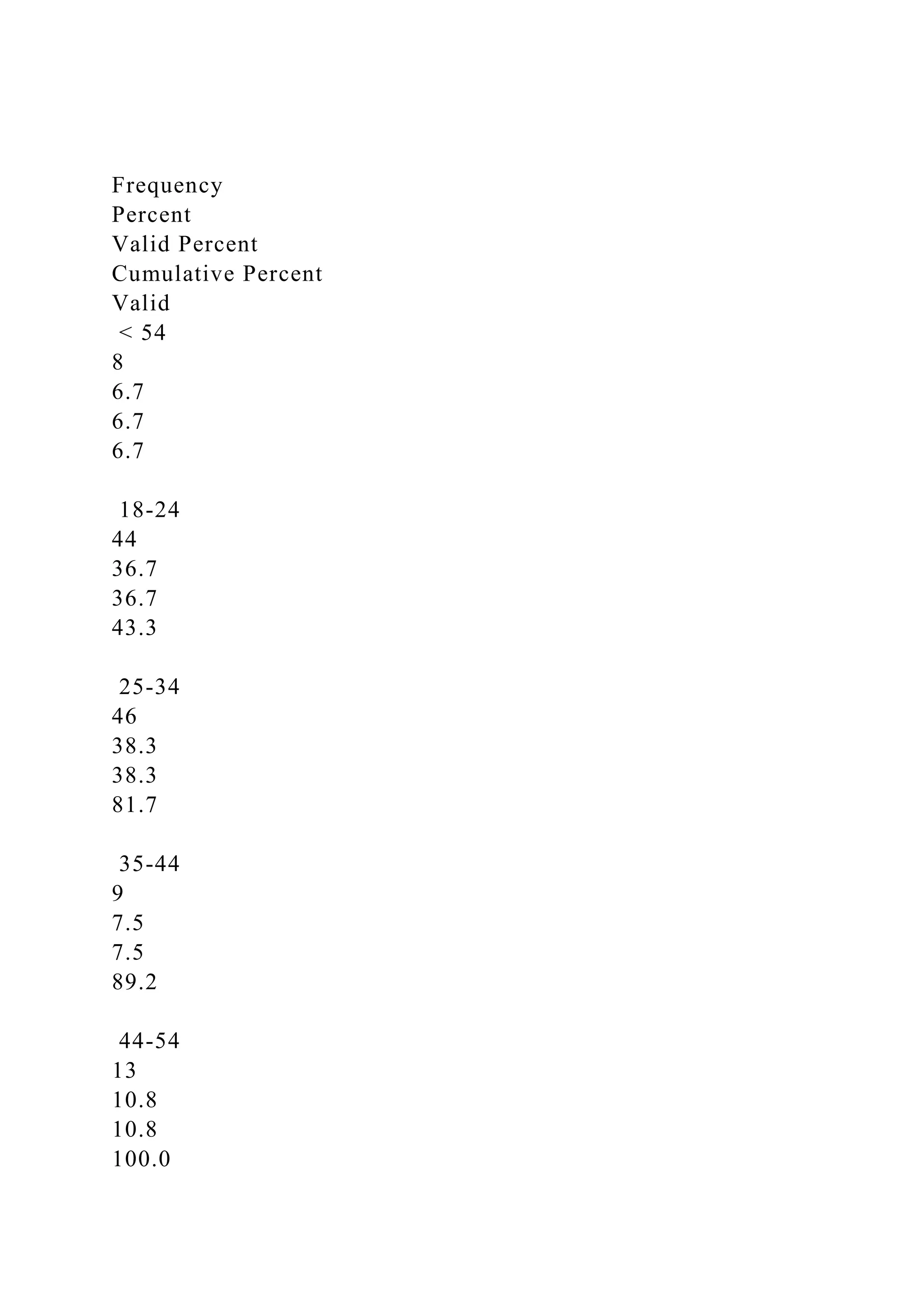

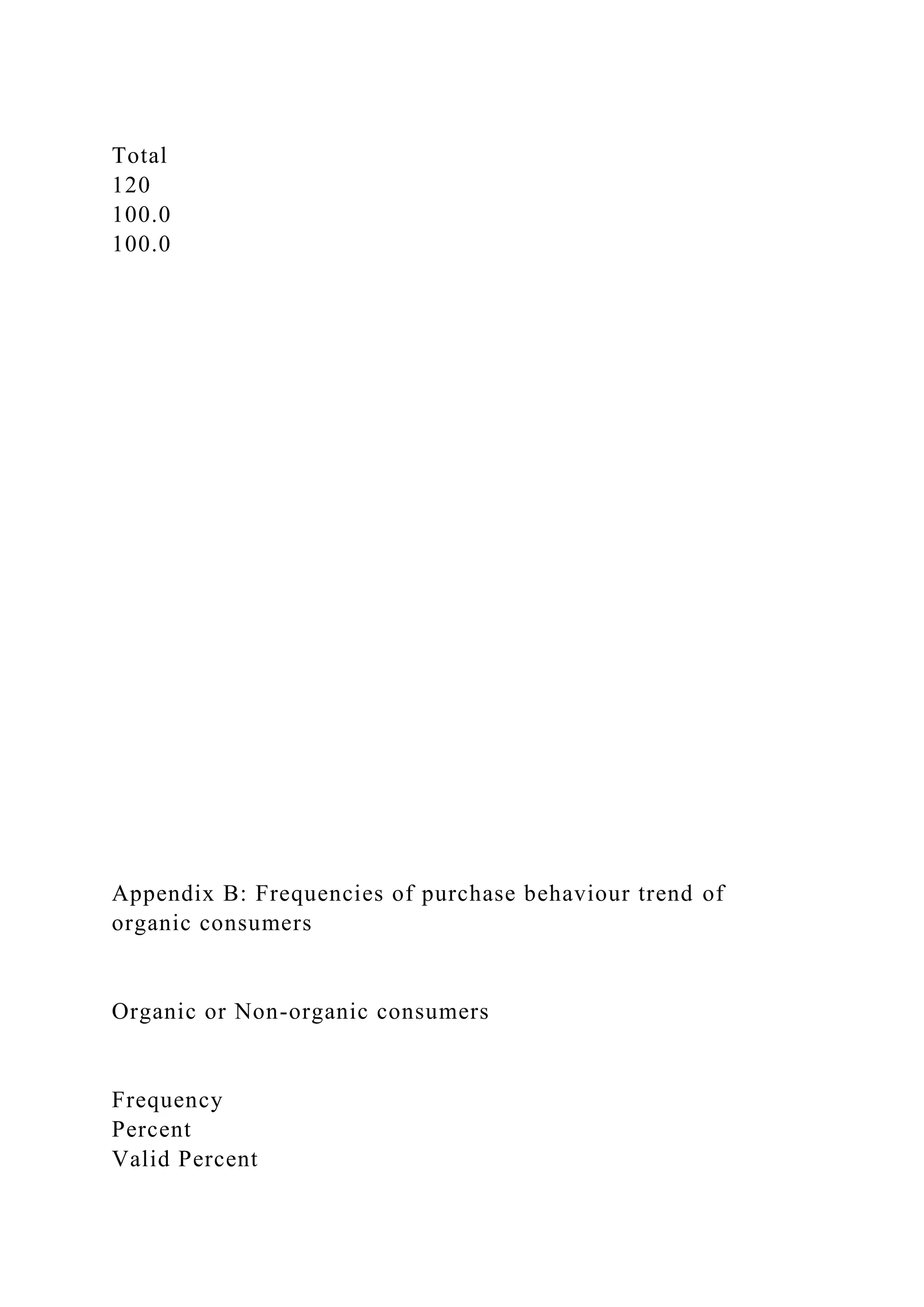

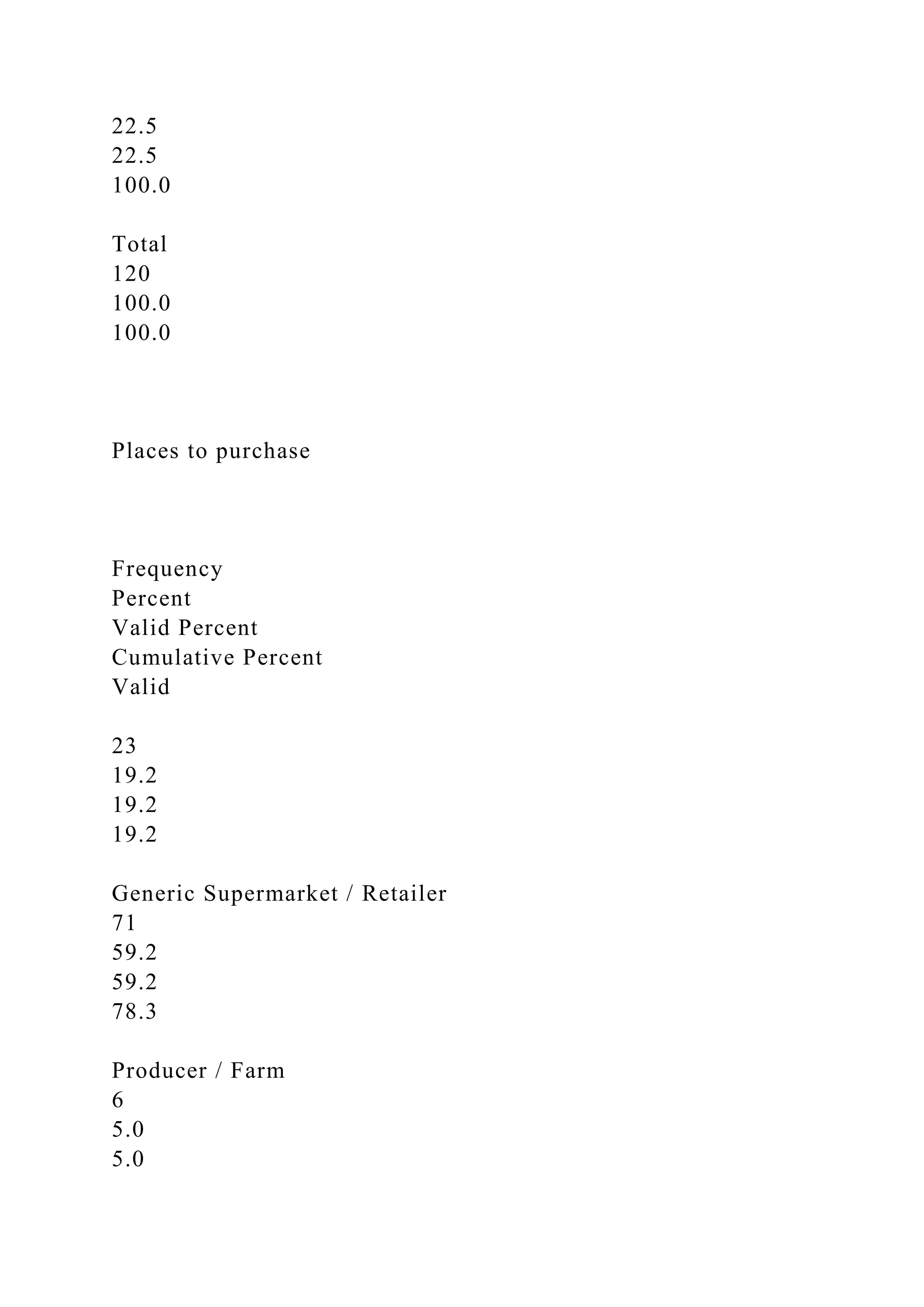

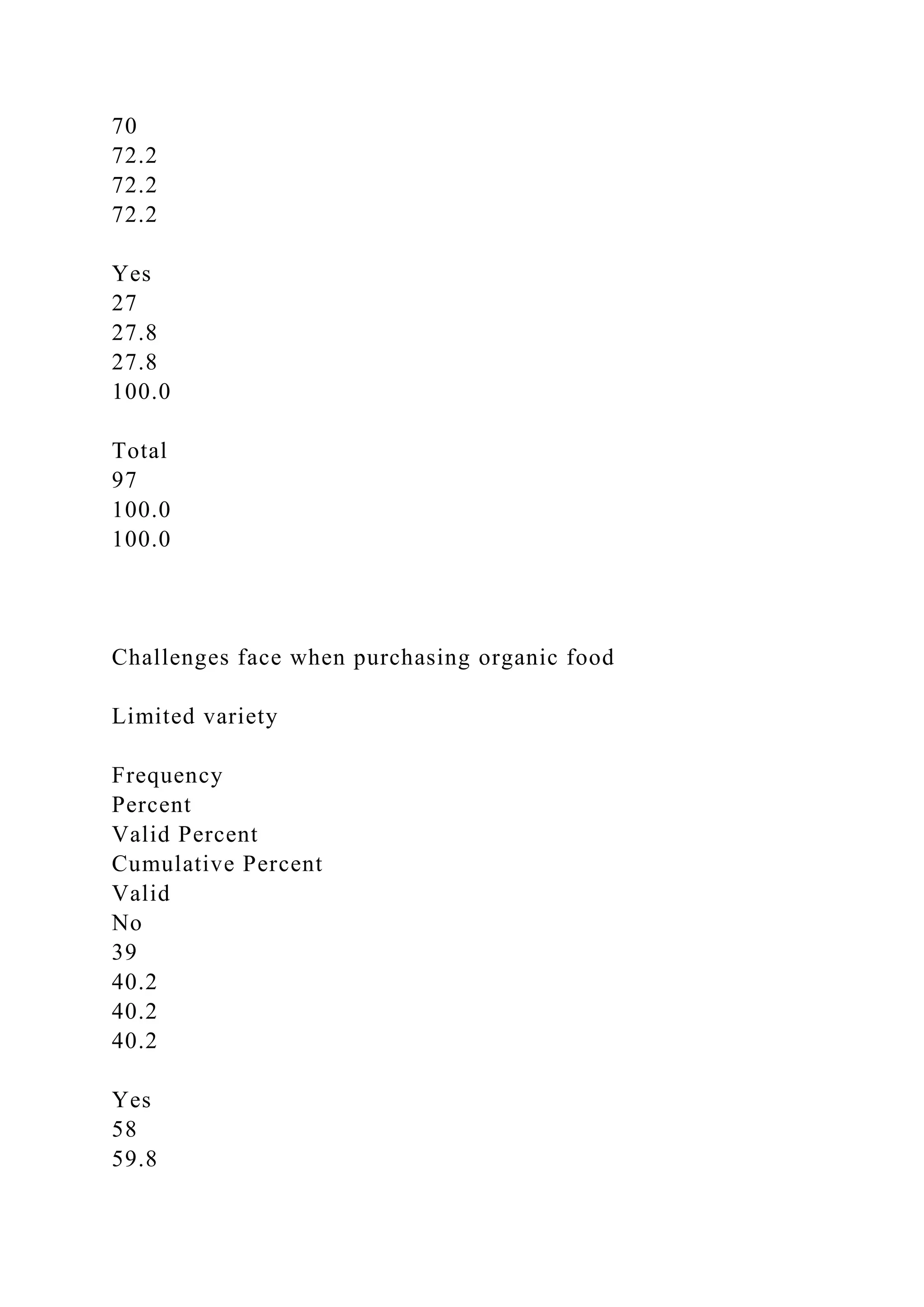

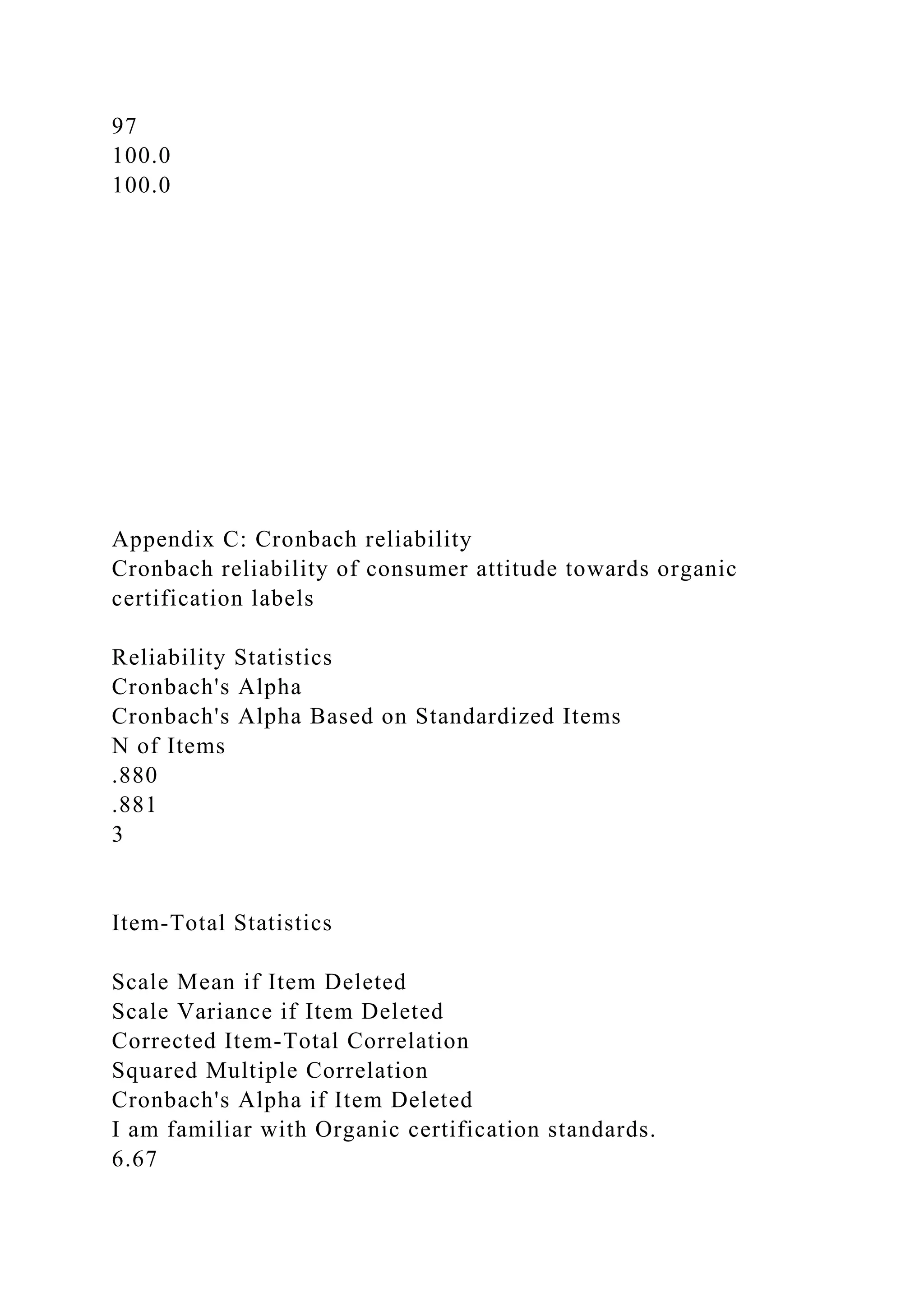

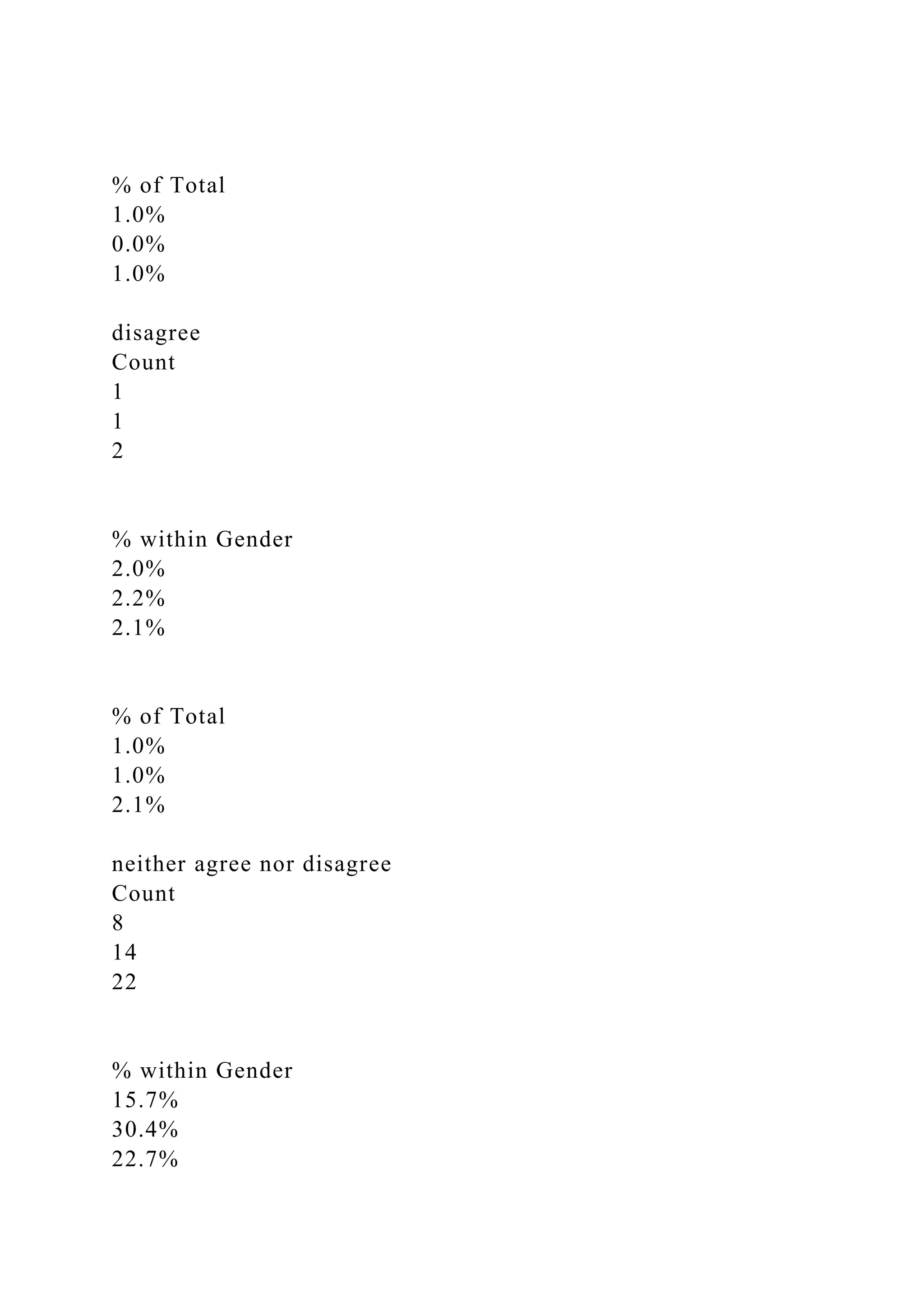

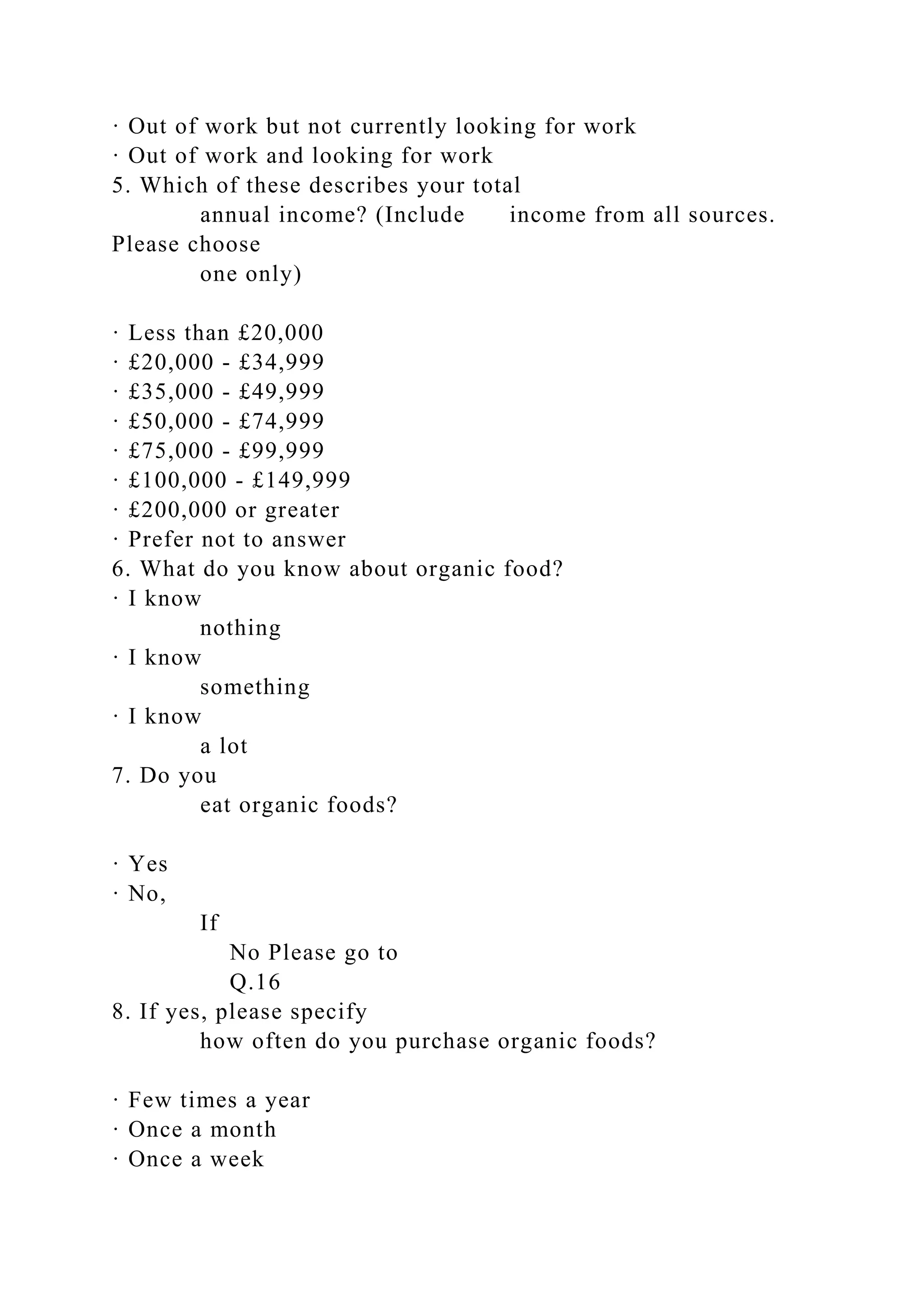

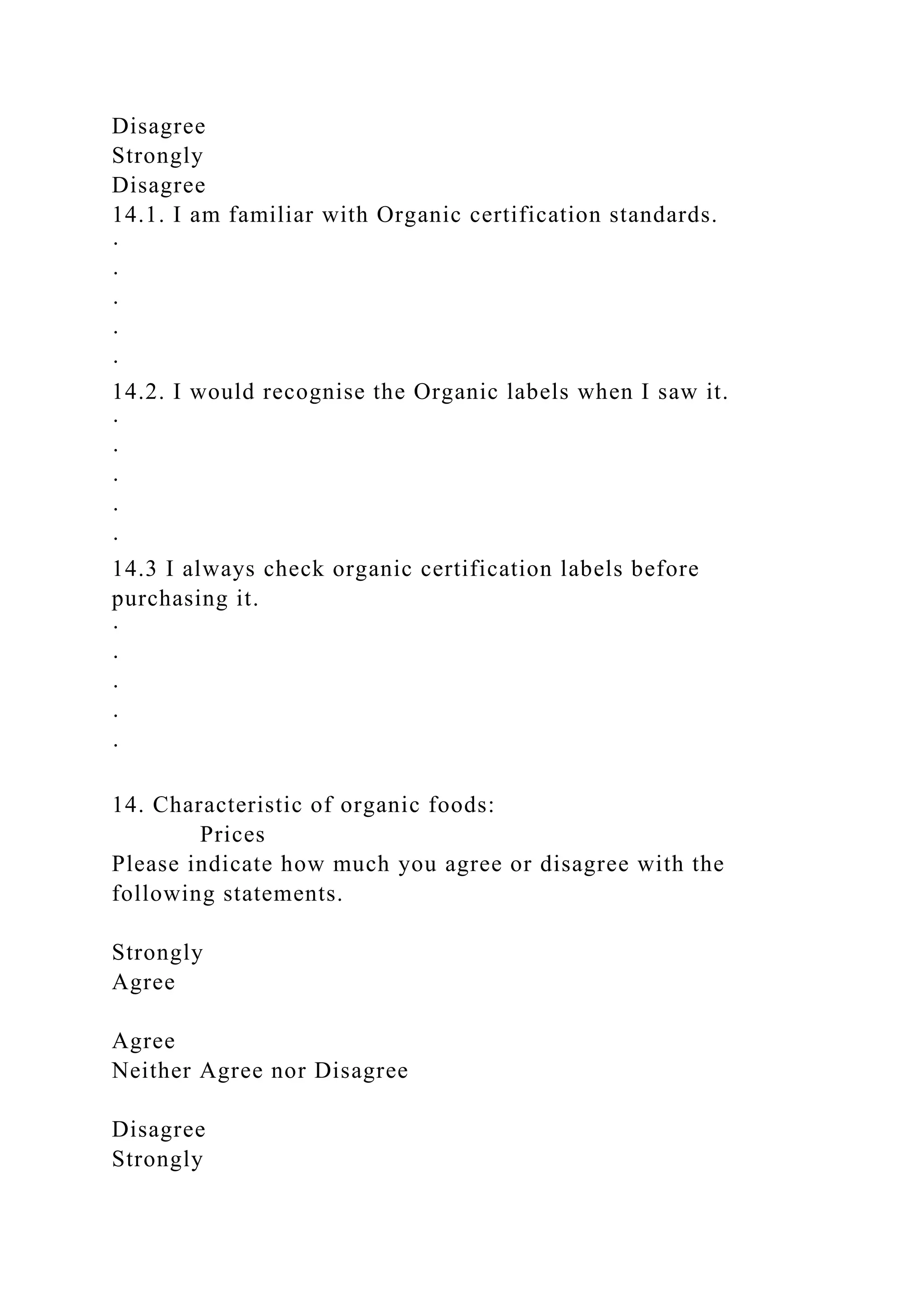

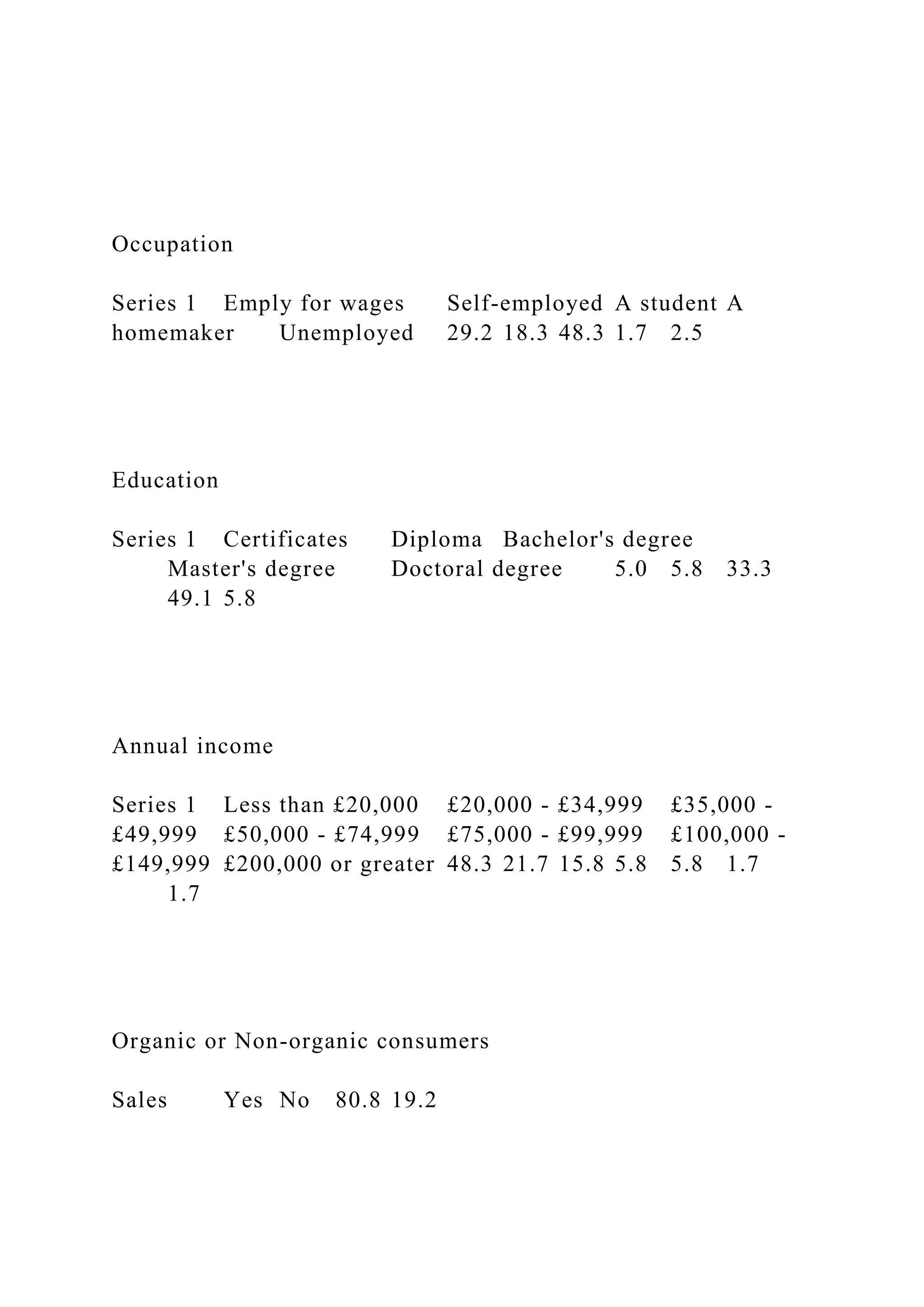

![Reasons for not eating organic food

Reasons for not eating organic foo d It's too expensive

It's not available where I shop I don't think it's different

from conventional food I don't like the taste 4.2 4.2 8.3

2.5

The frequency of organic consumers’ purchases

The frequenc y of organic consumers’ purchases Few times a

year Once a month Once a week Several times a week

Everyday 14.2 16.7 25.0 22.5 2.5

Categories

Categories

[CATEGORY NAME]

73.2%

[CATEGORY NAME]

92.8%

[CATEGORY NAME]

39.2%

Red meat

27.8%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/submittedinpartfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof-230119024927-31555ff9/75/Submitted-in-part-fulfilment-of-the-requirements-for-the-degree-of-docx-149-2048.jpg)

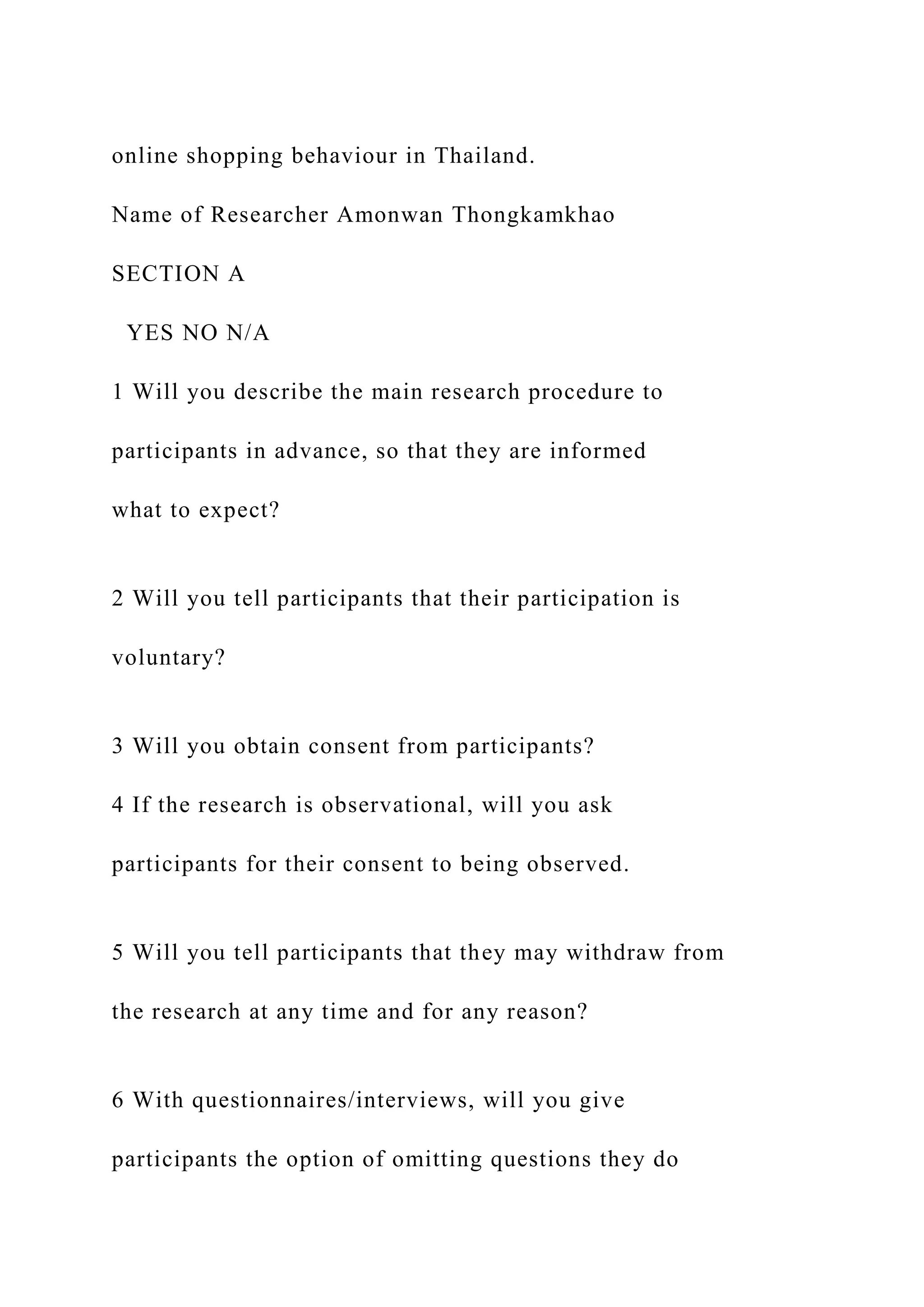

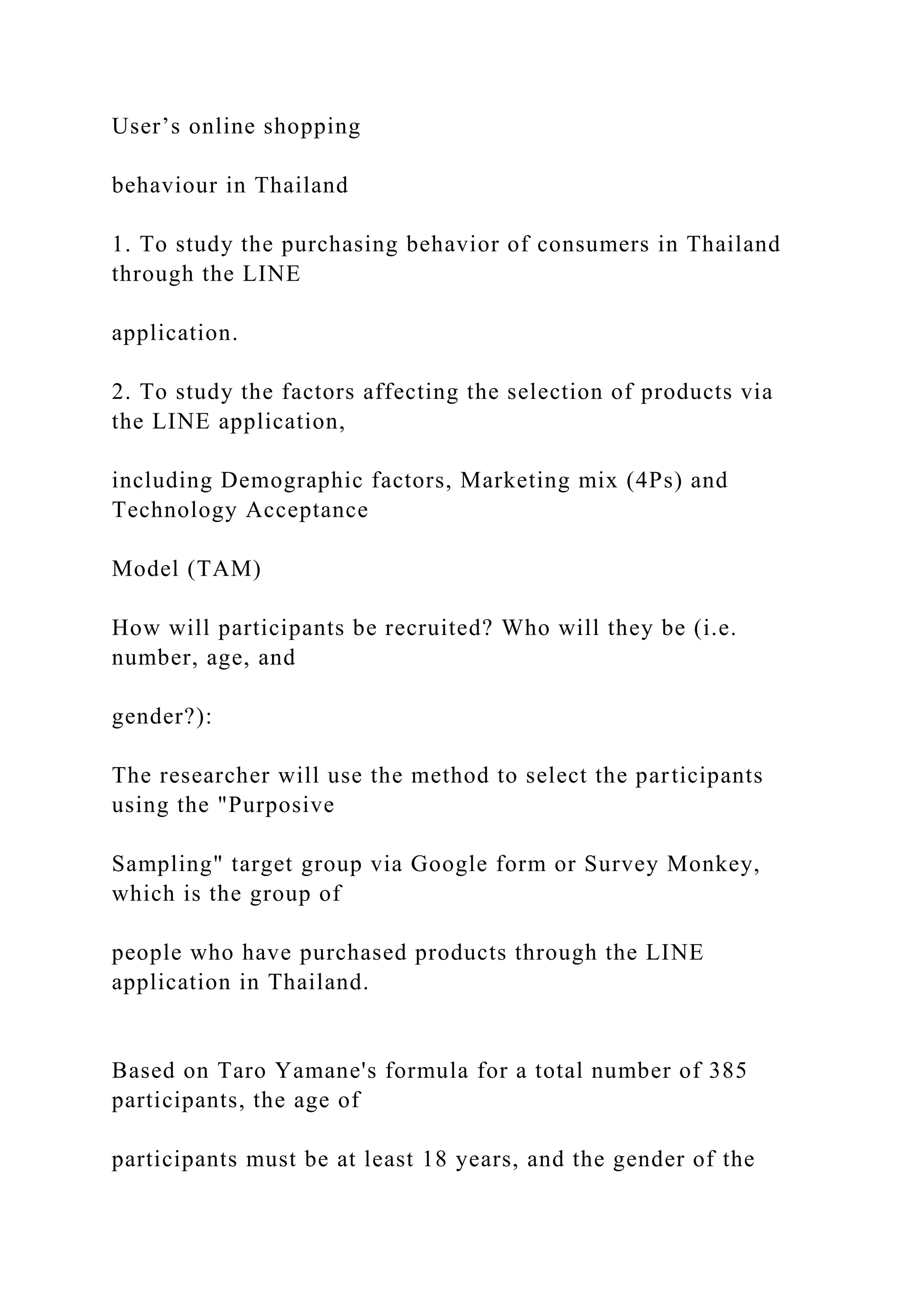

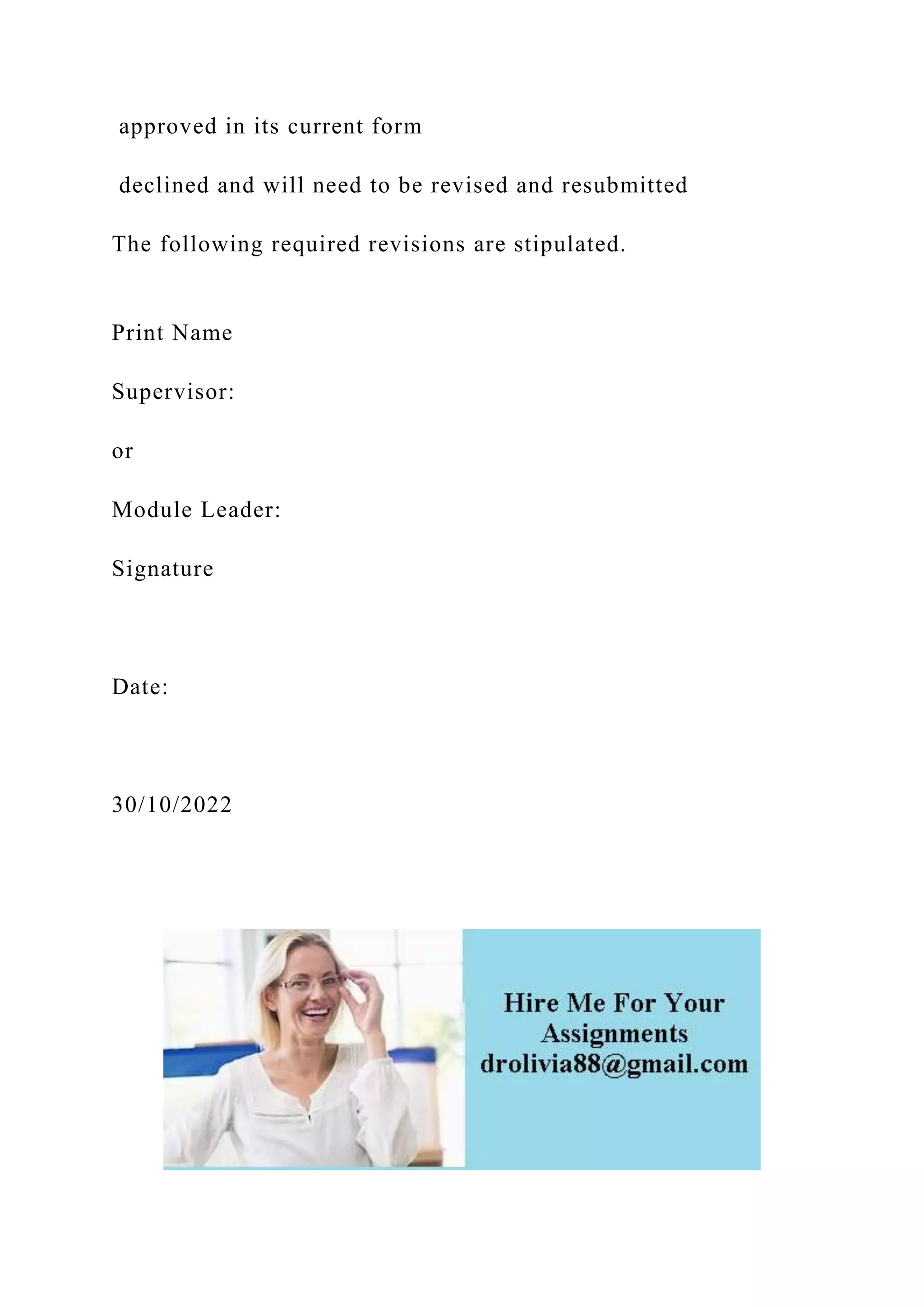

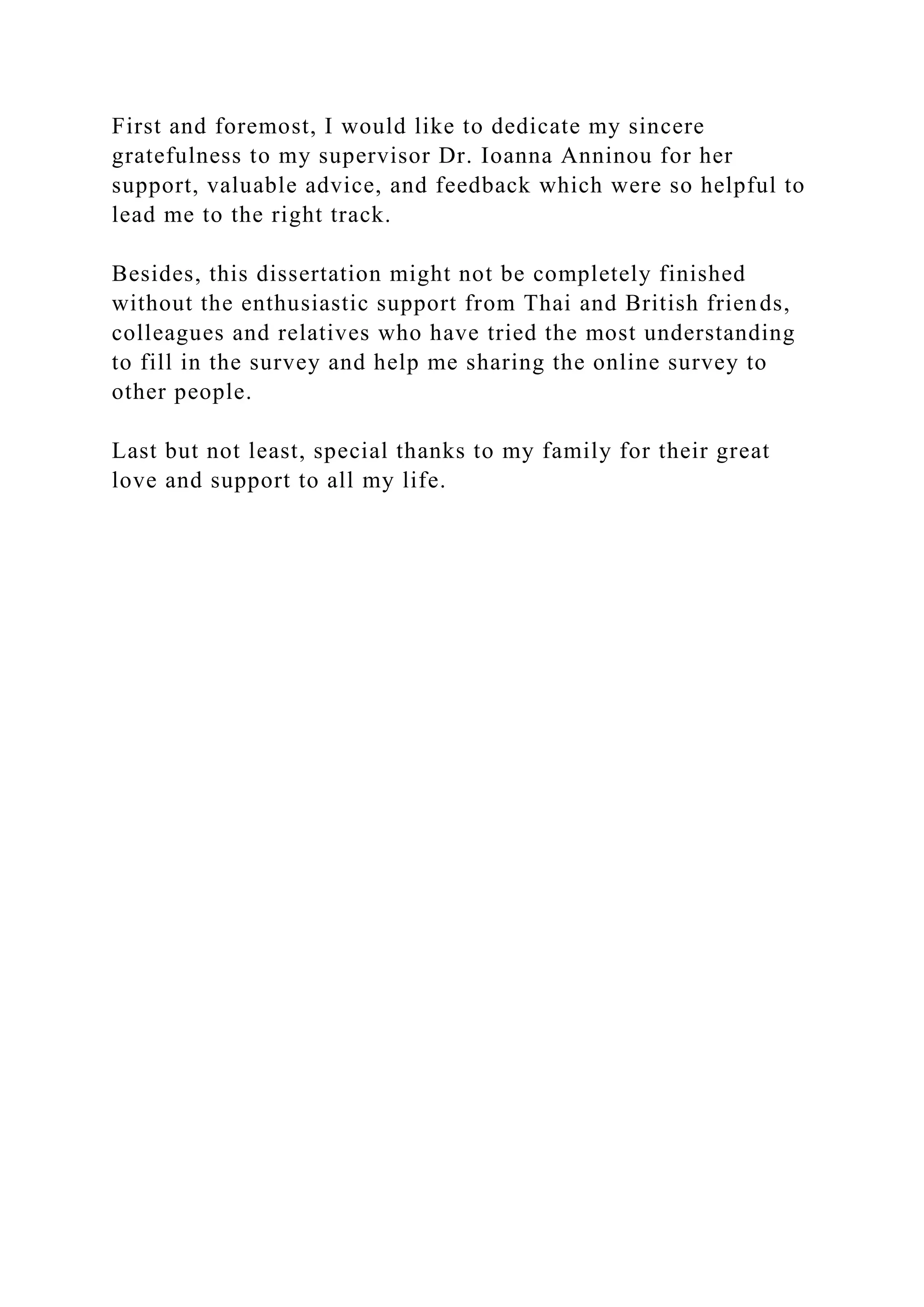

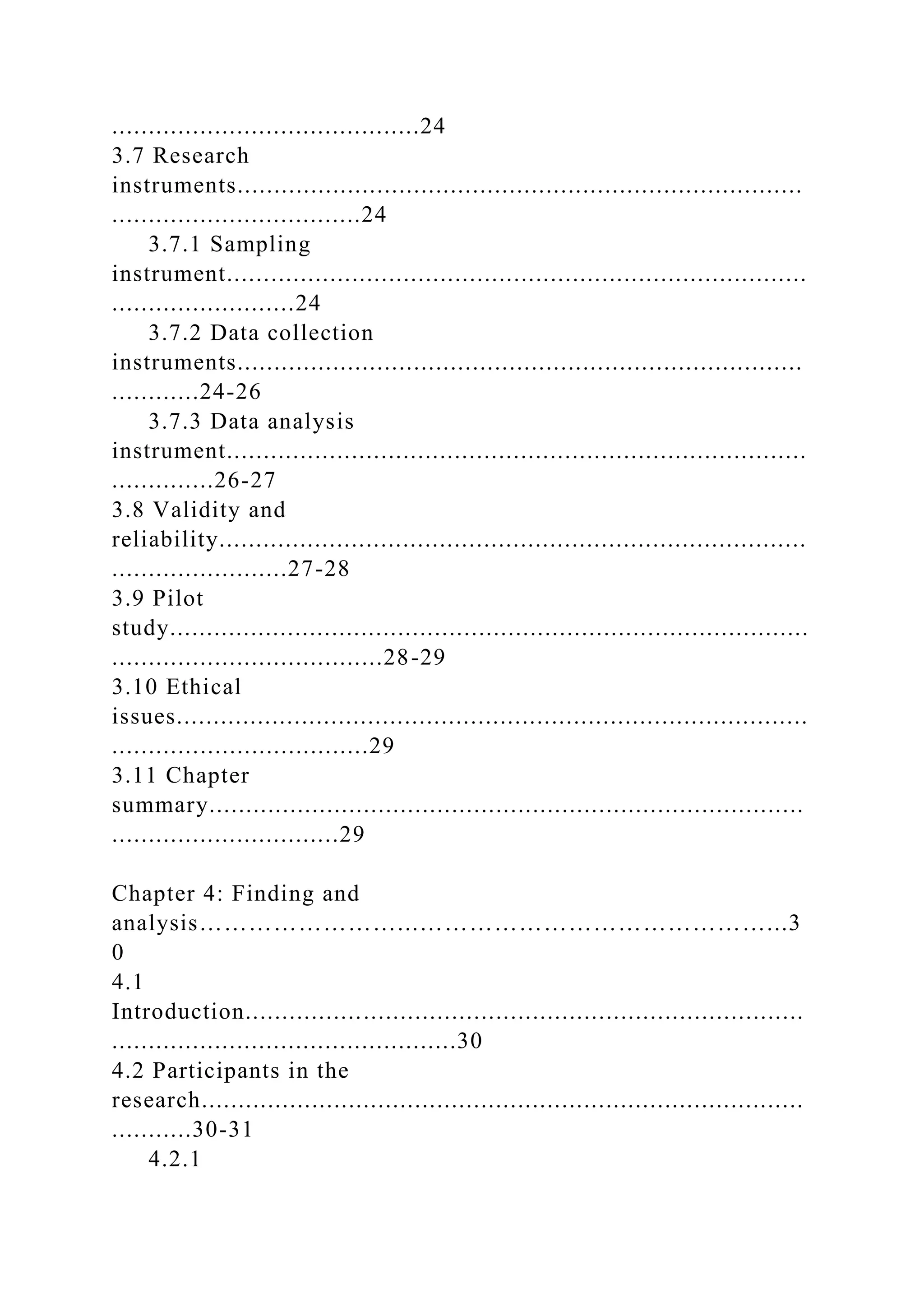

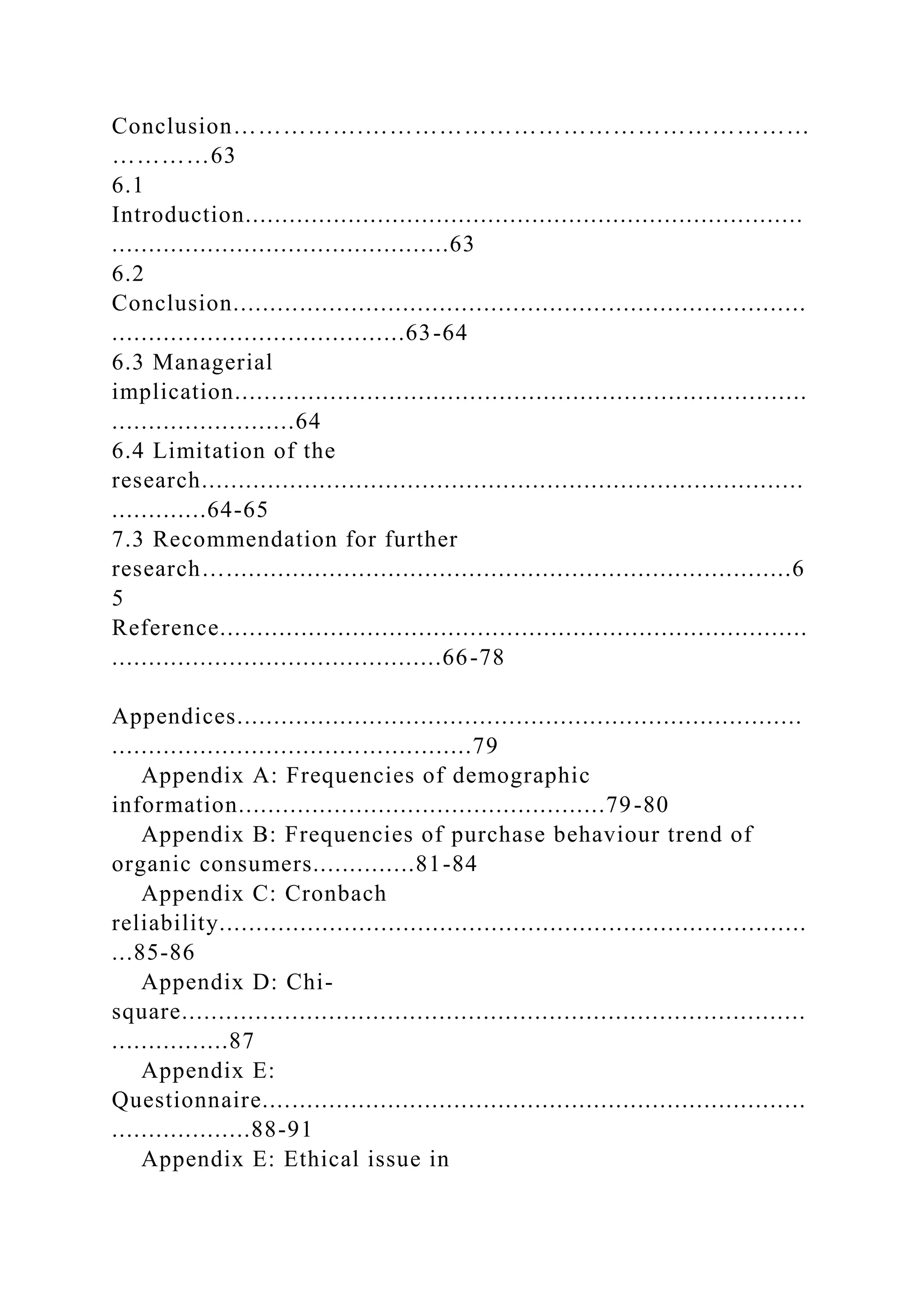

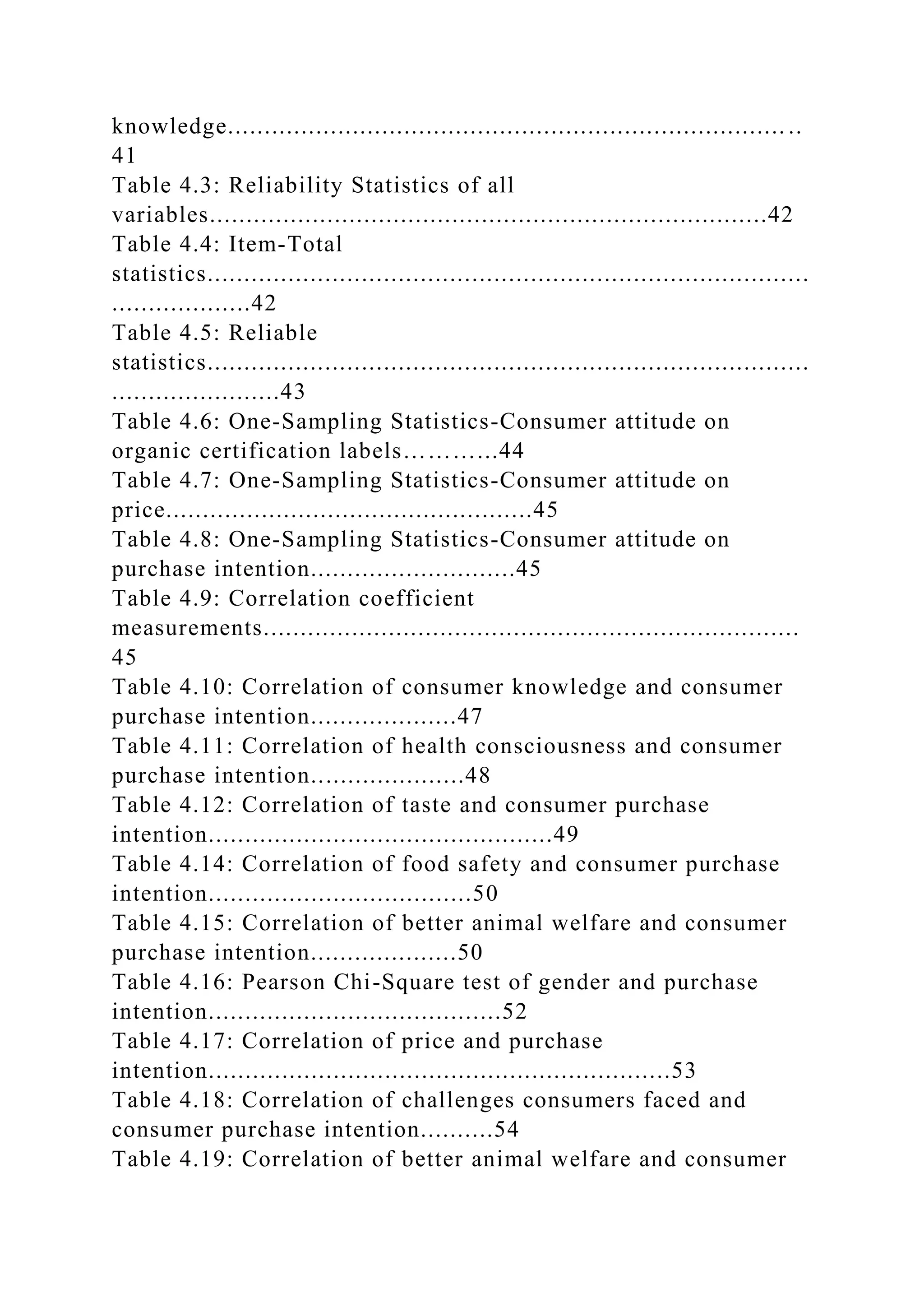

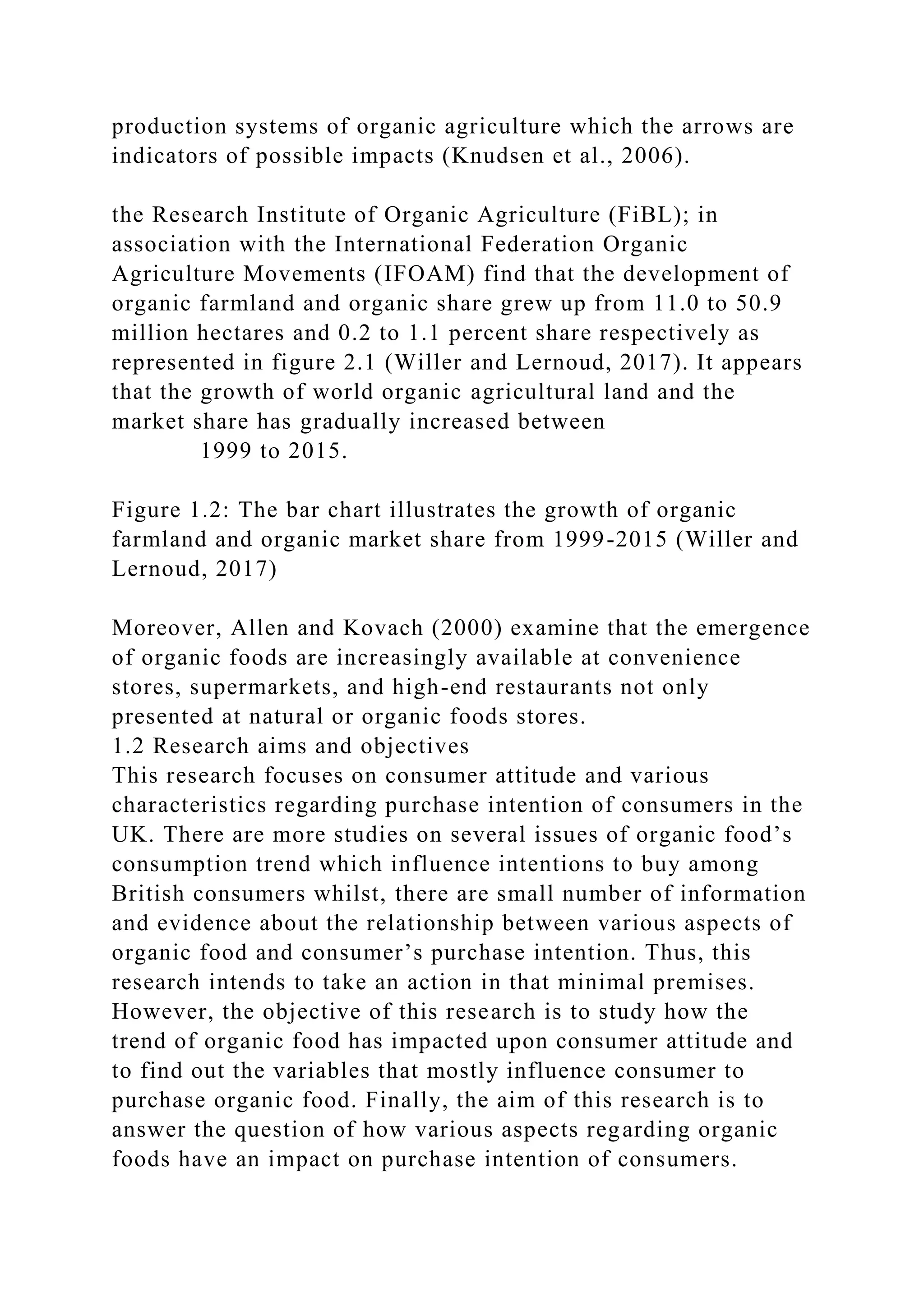

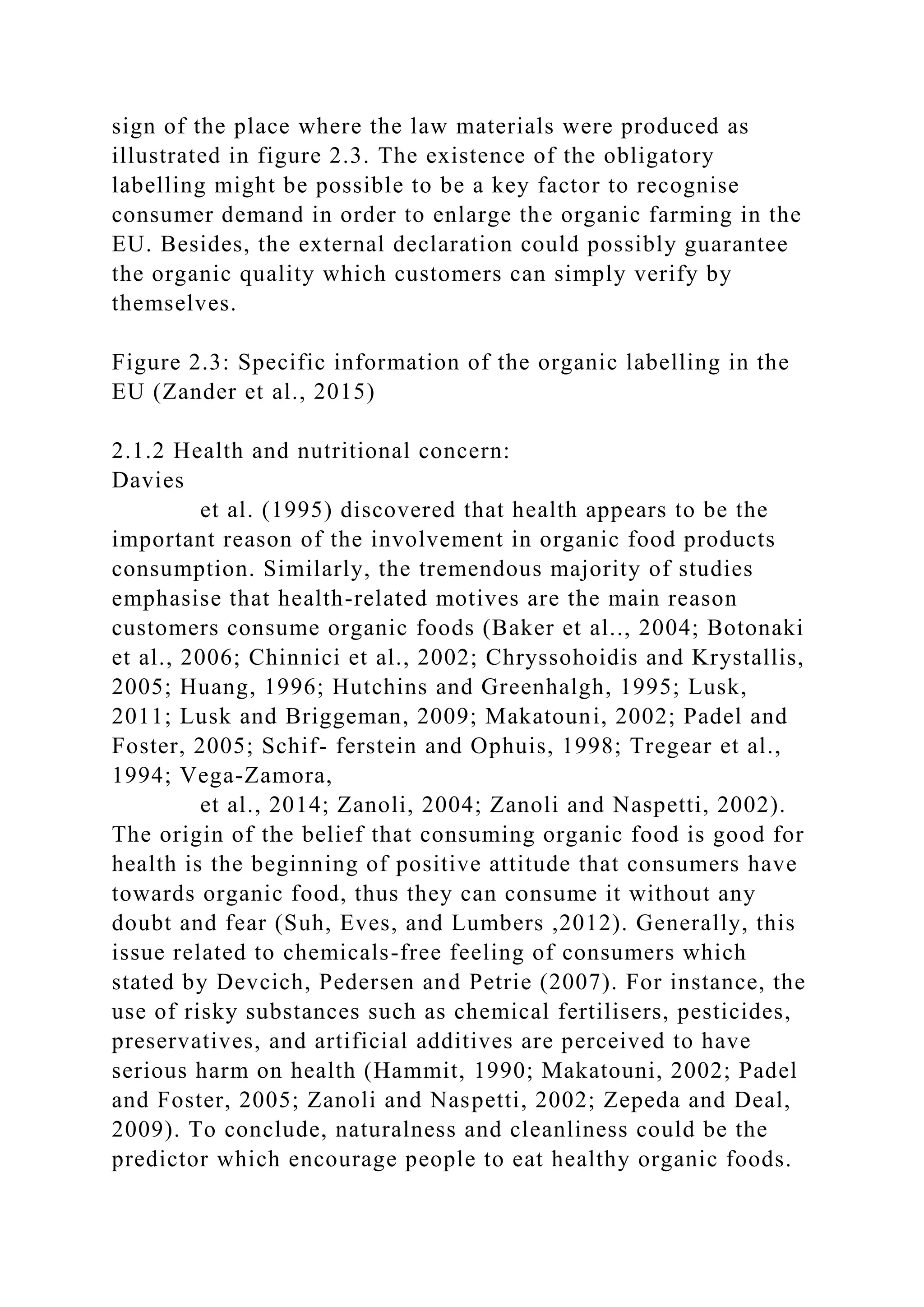

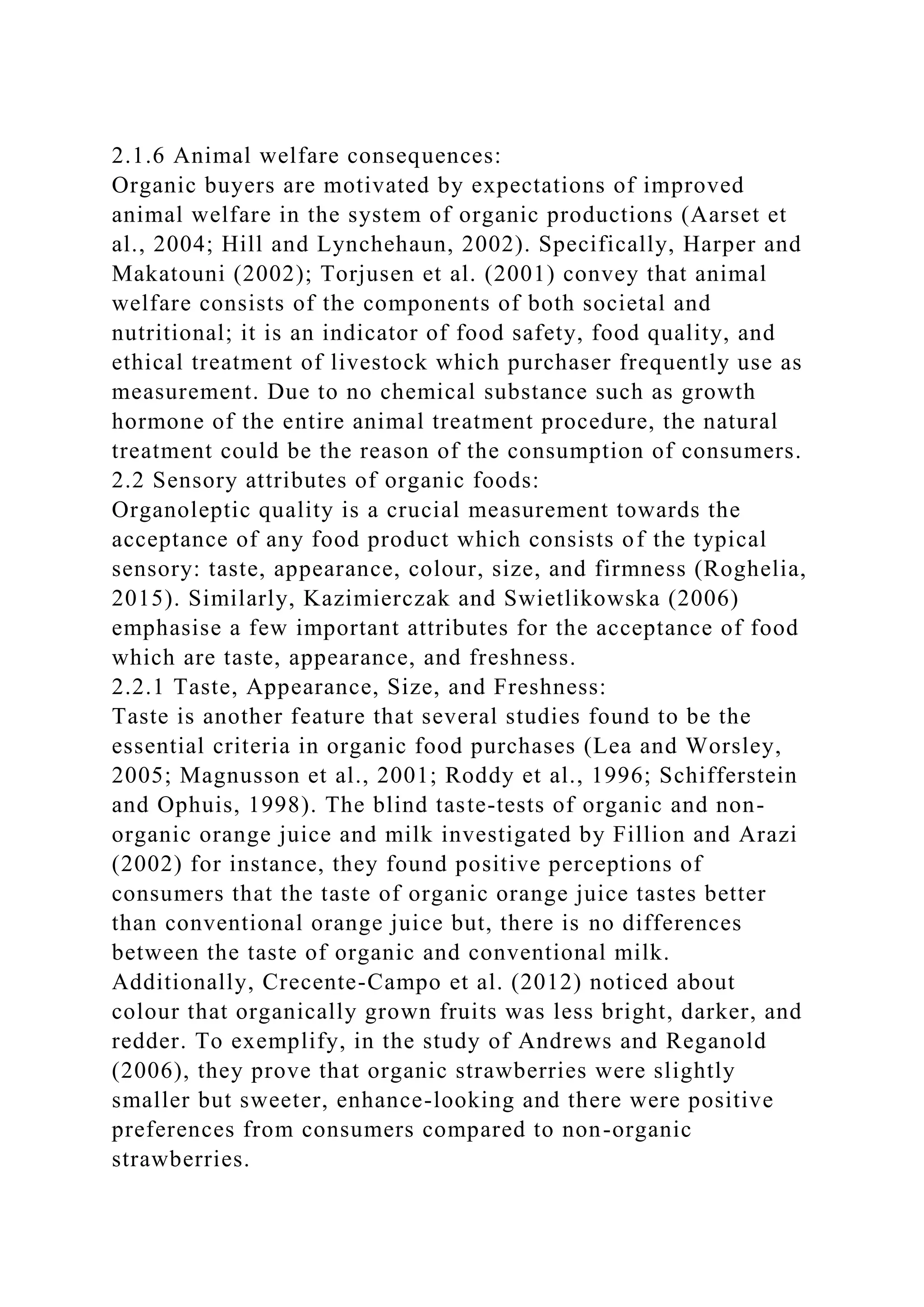

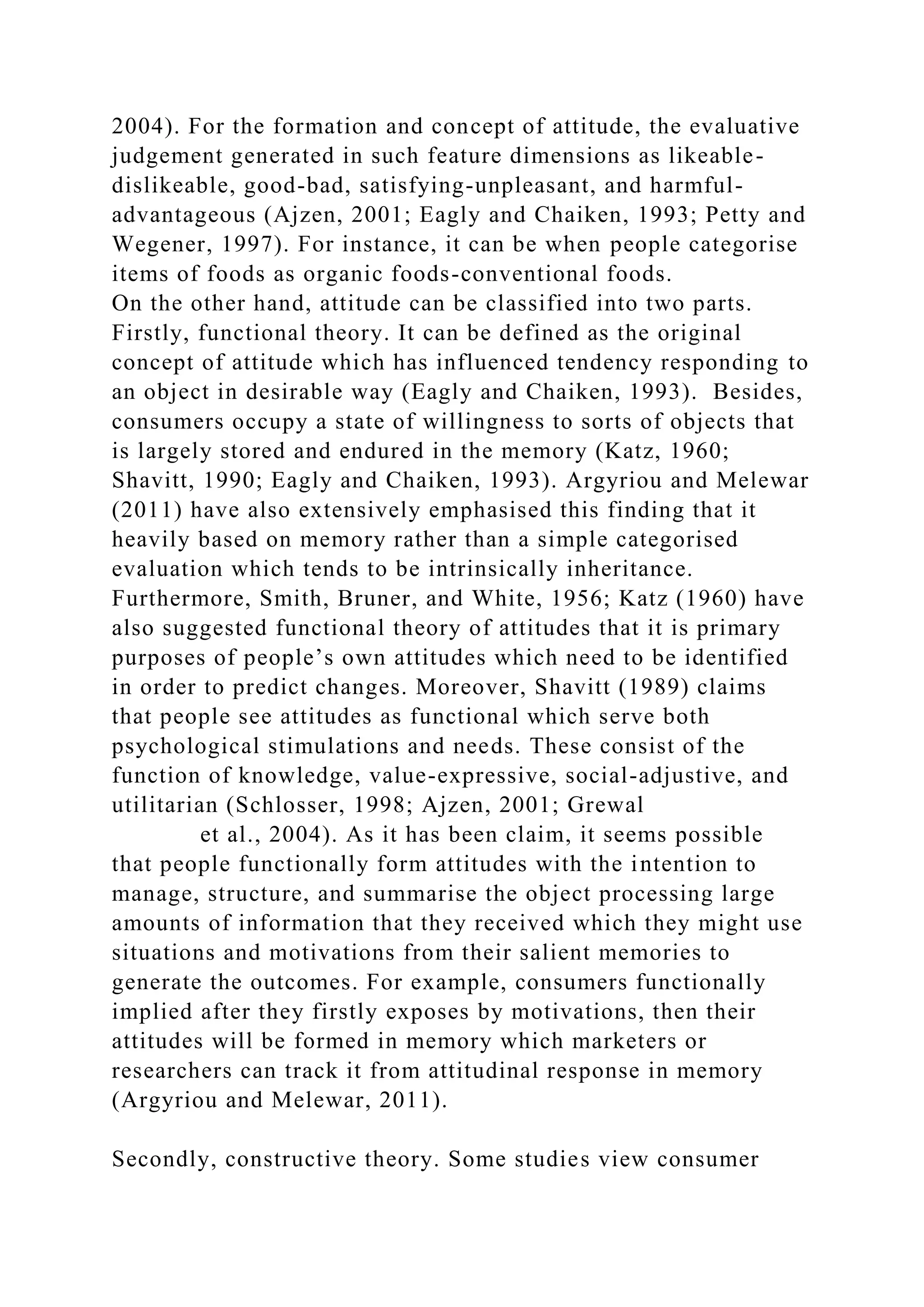

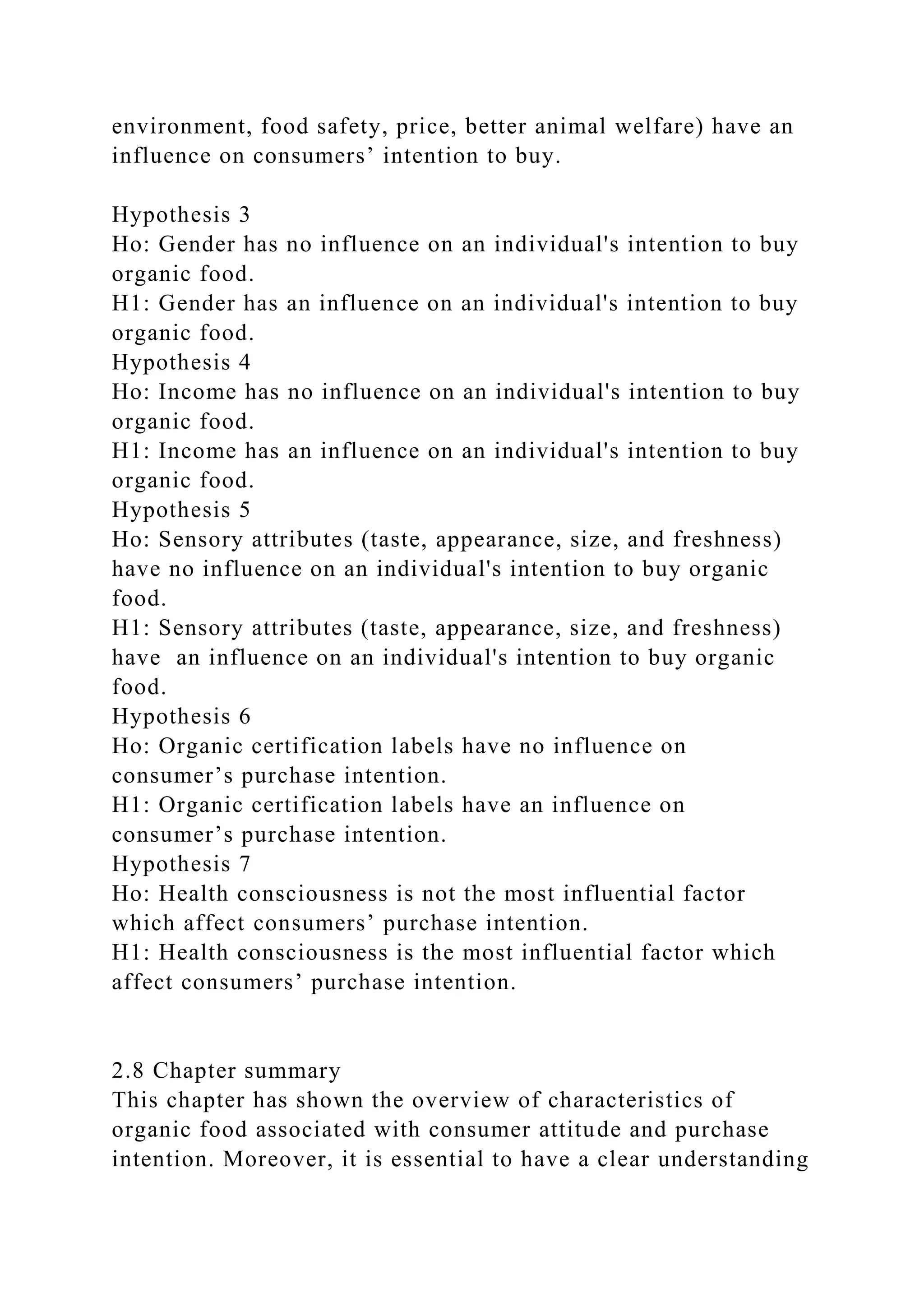

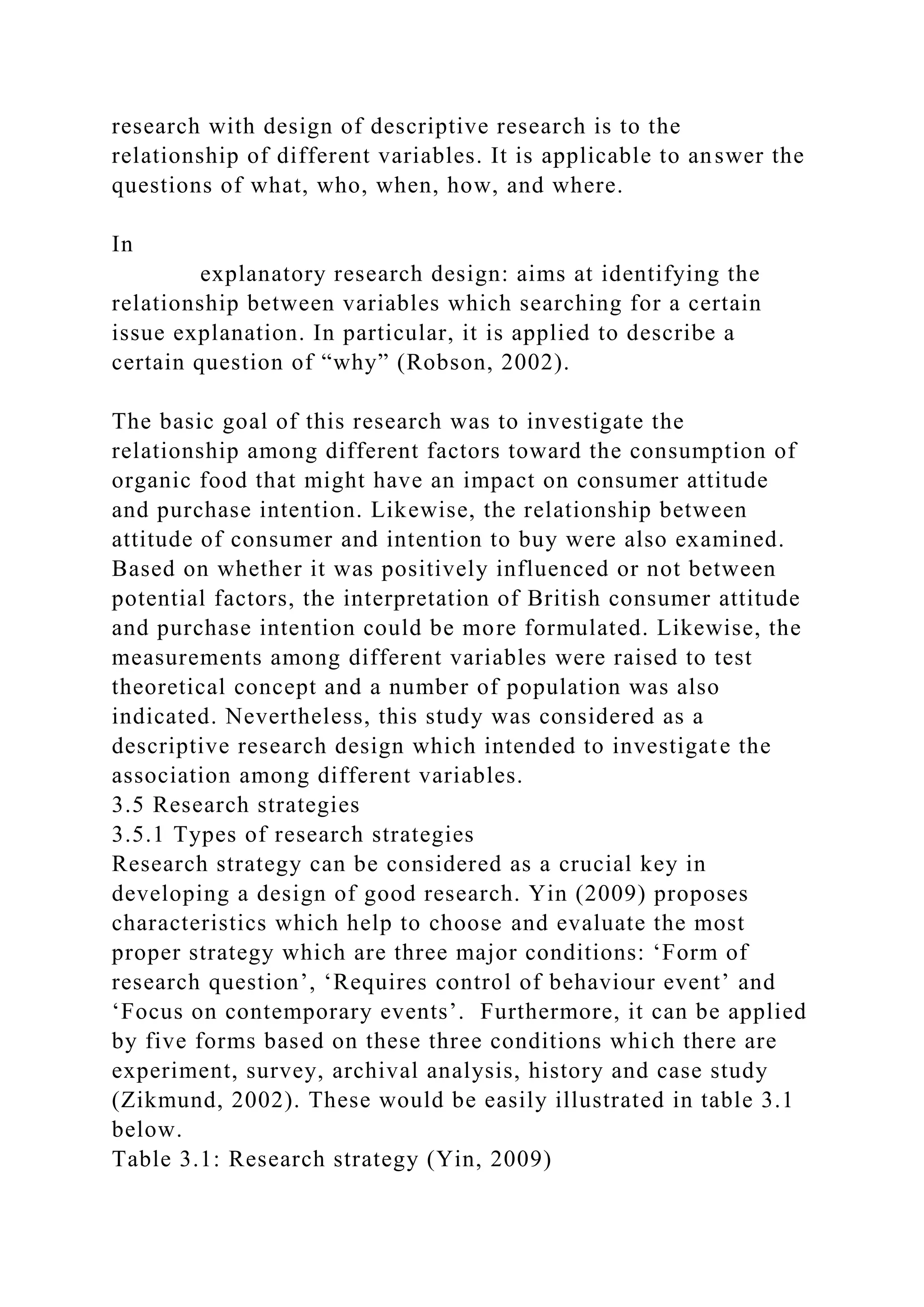

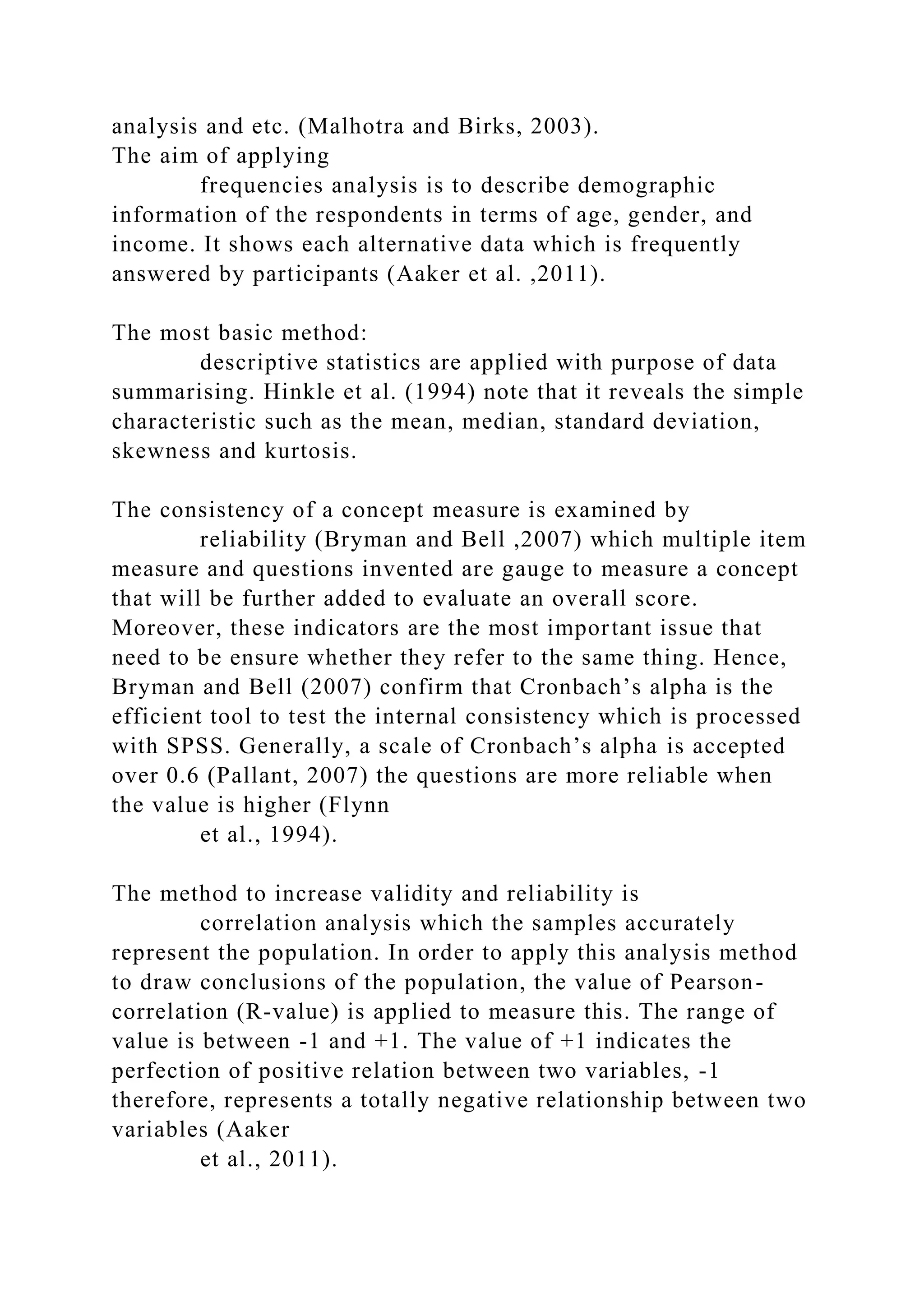

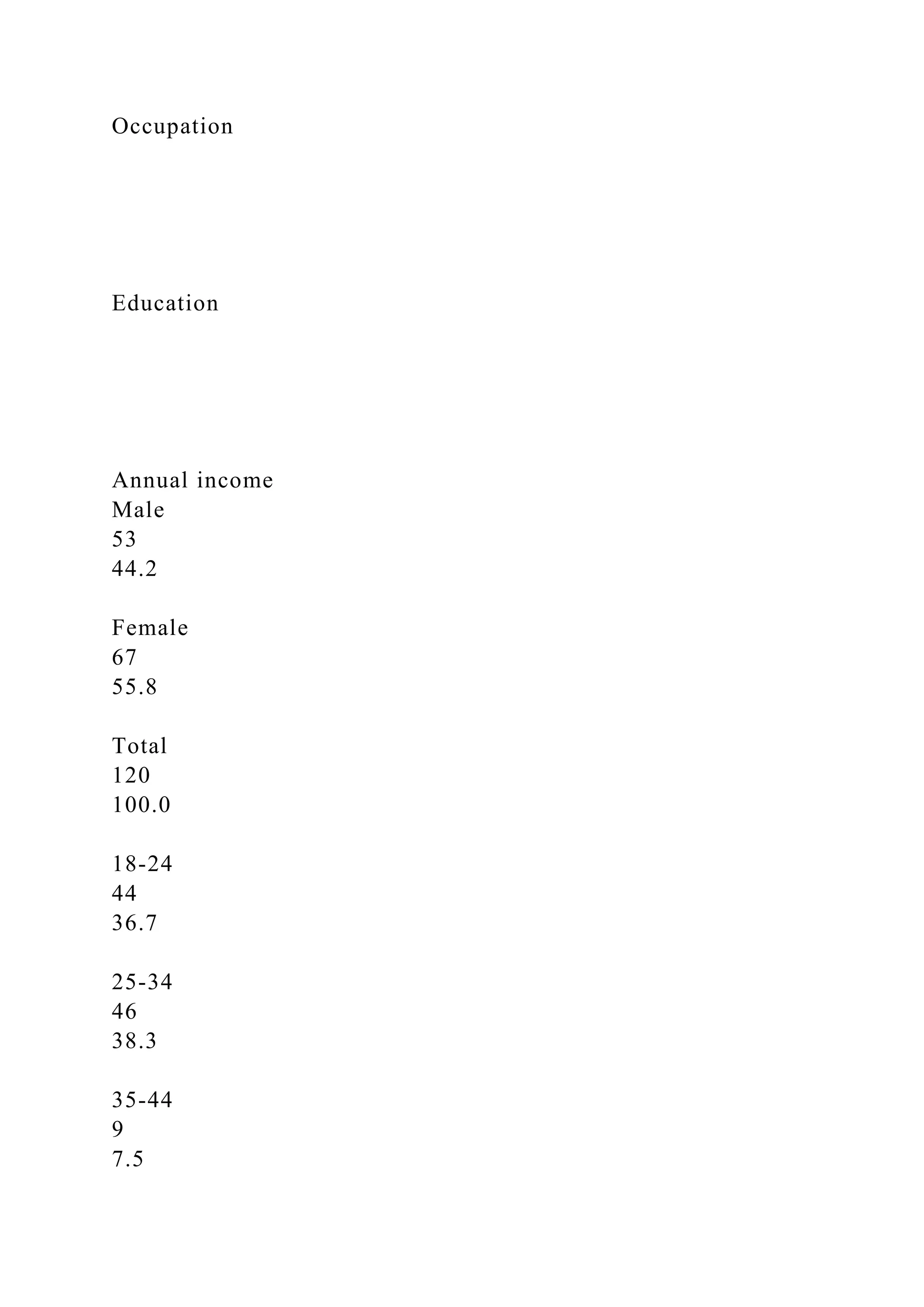

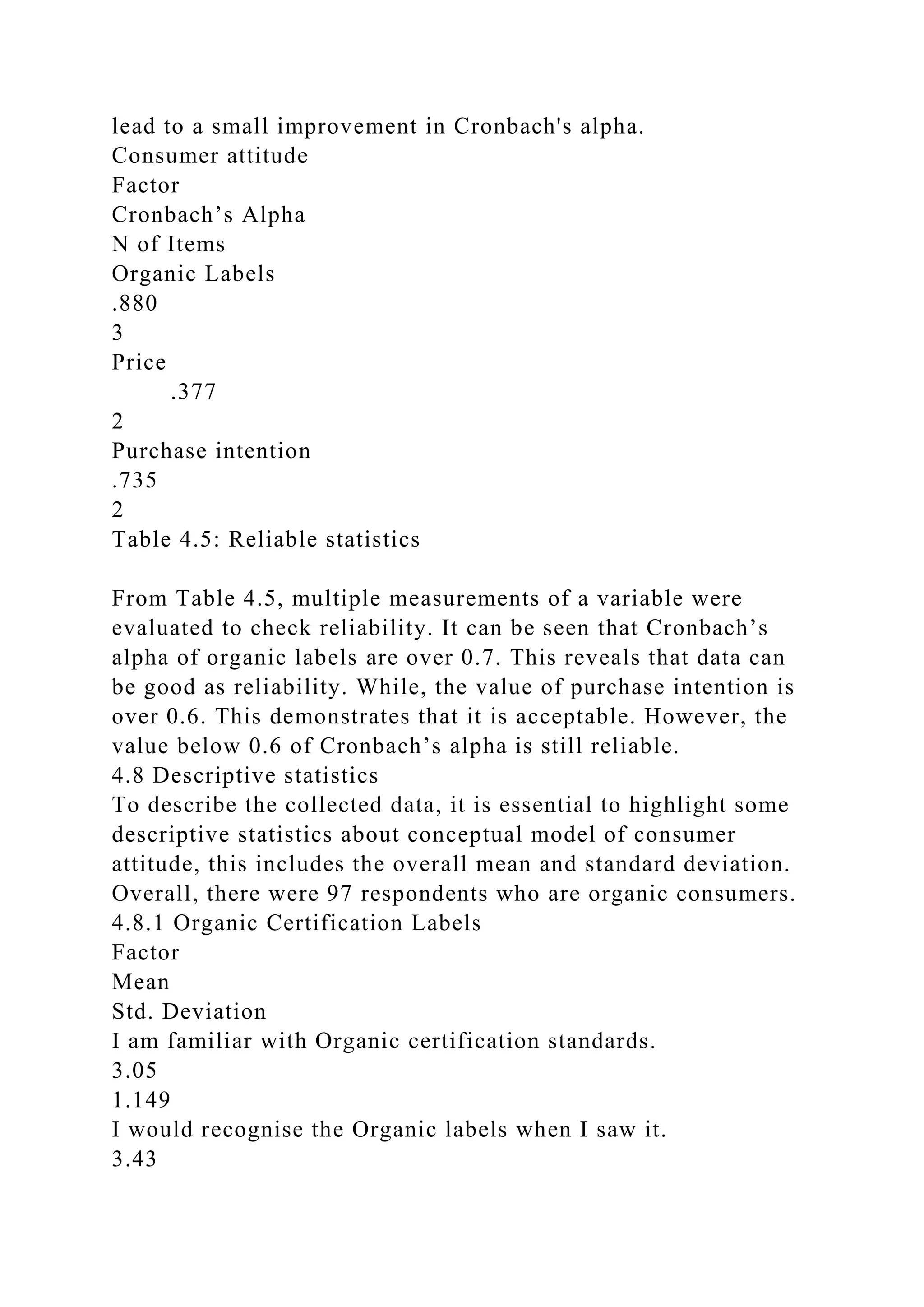

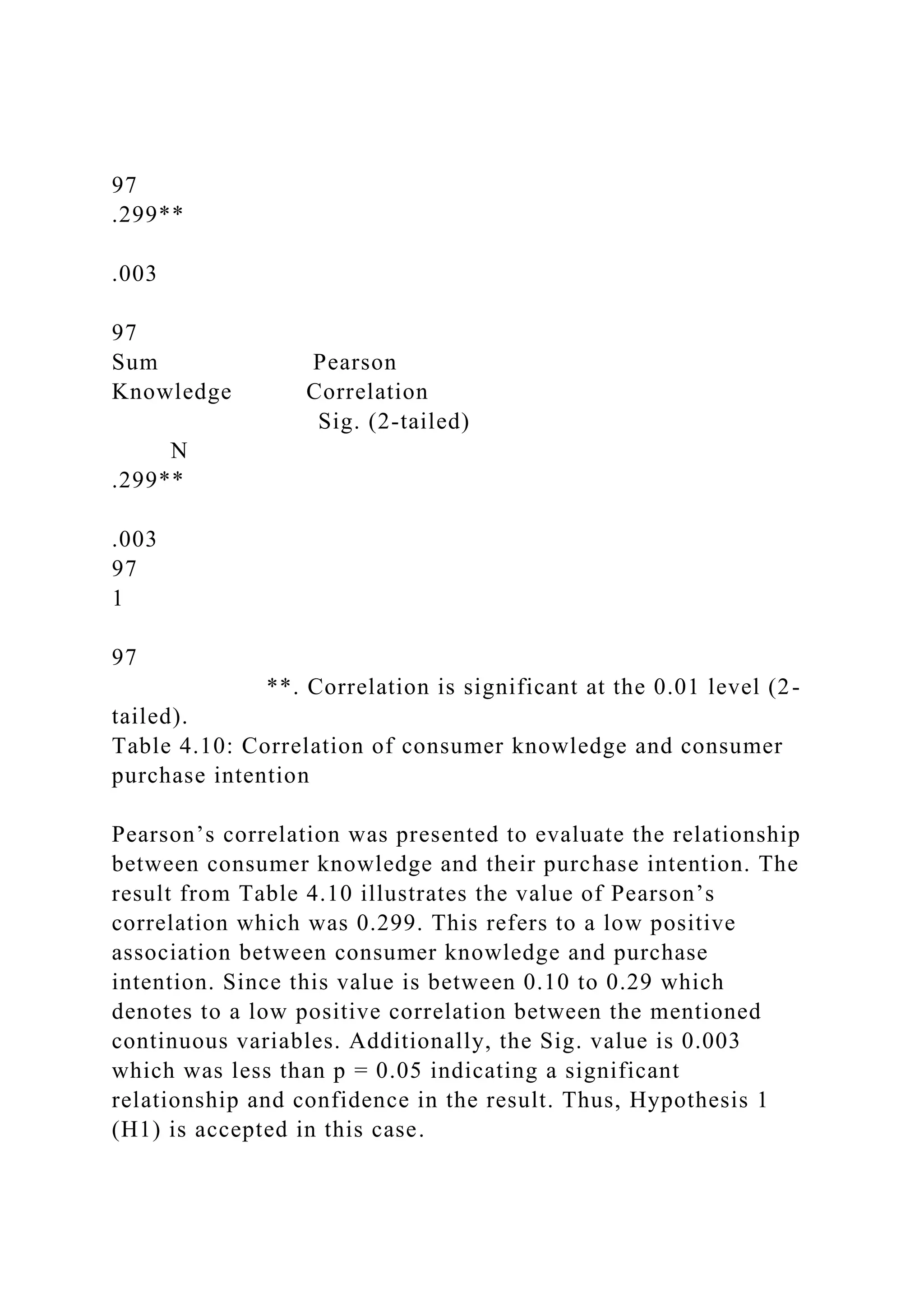

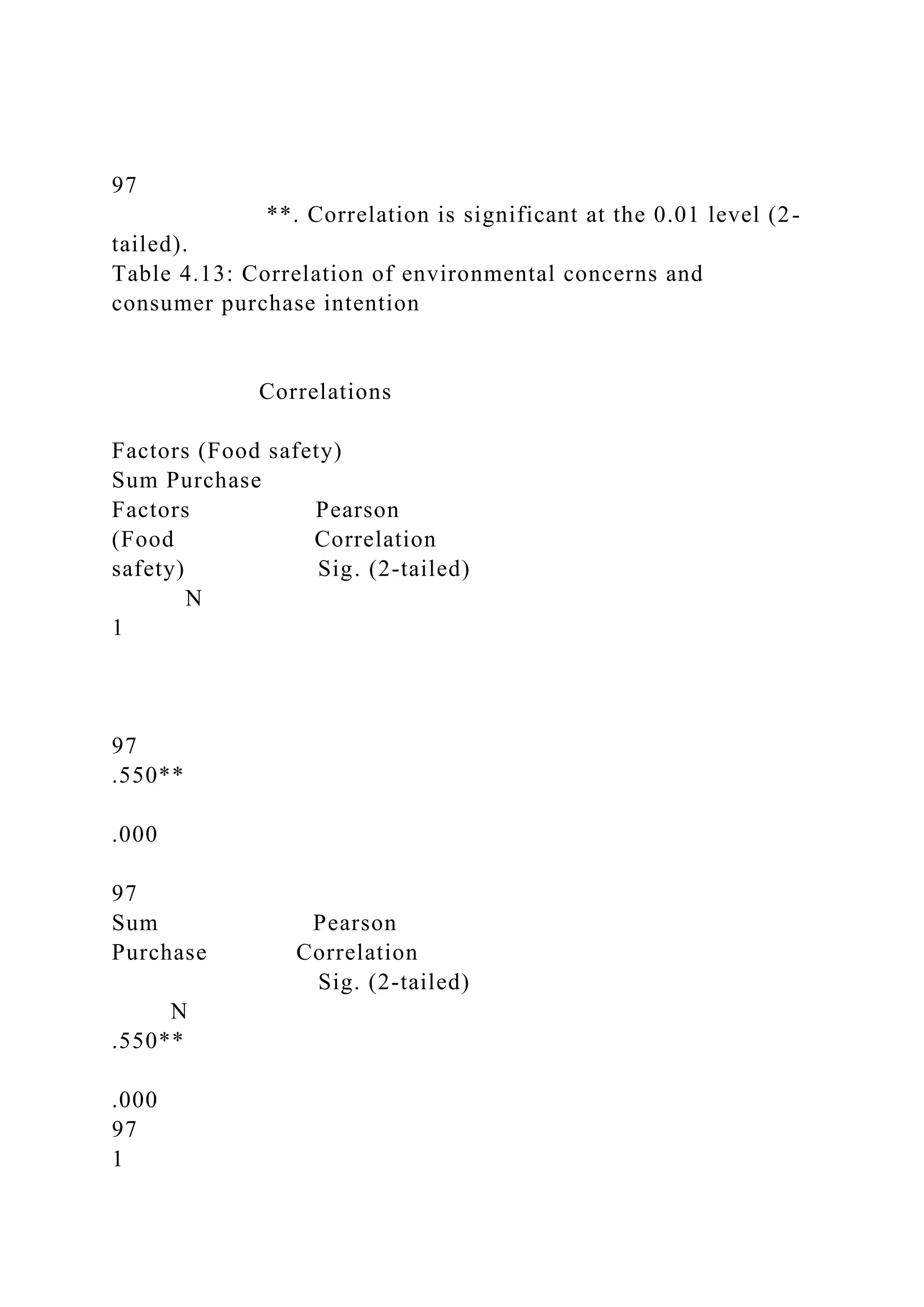

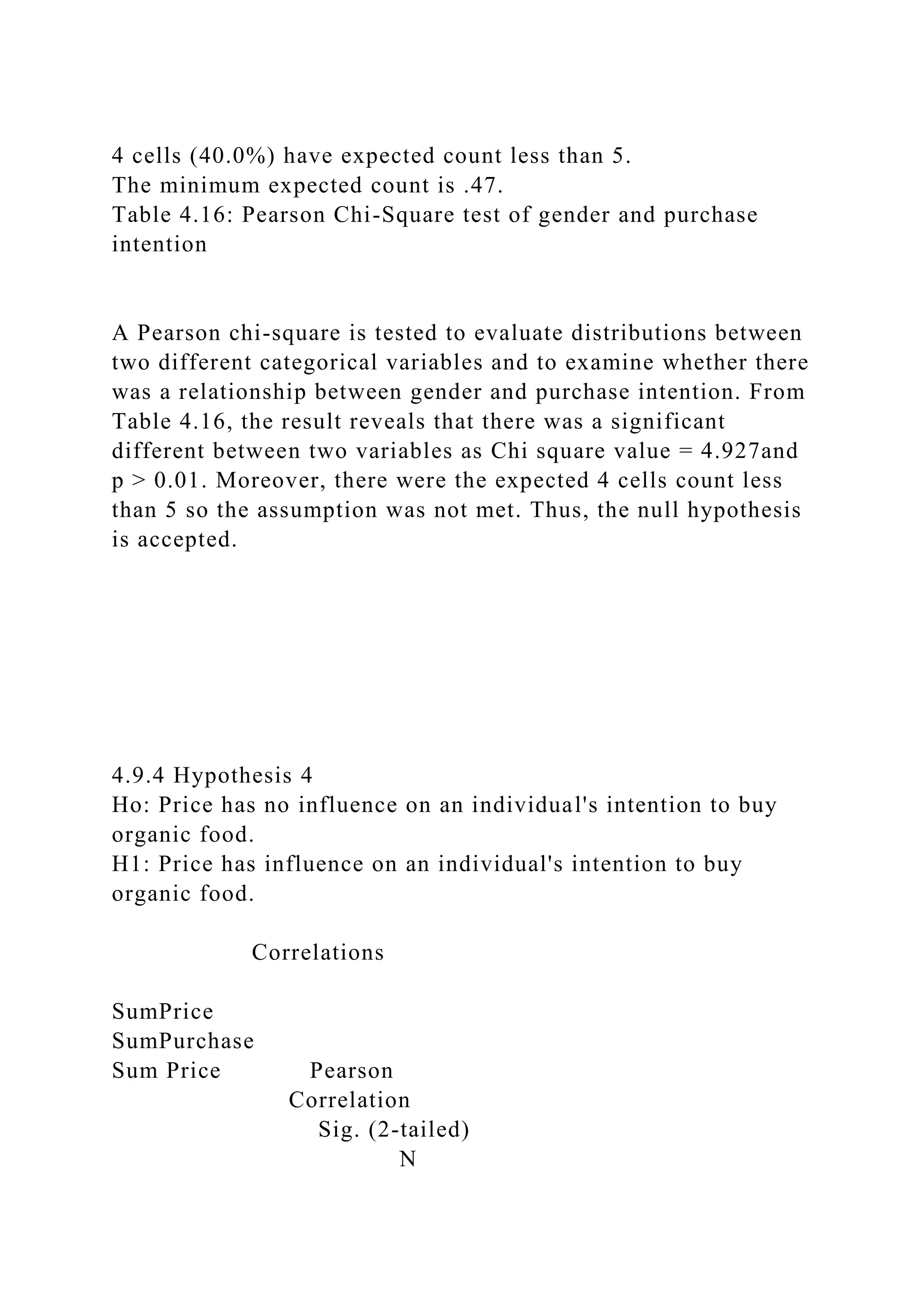

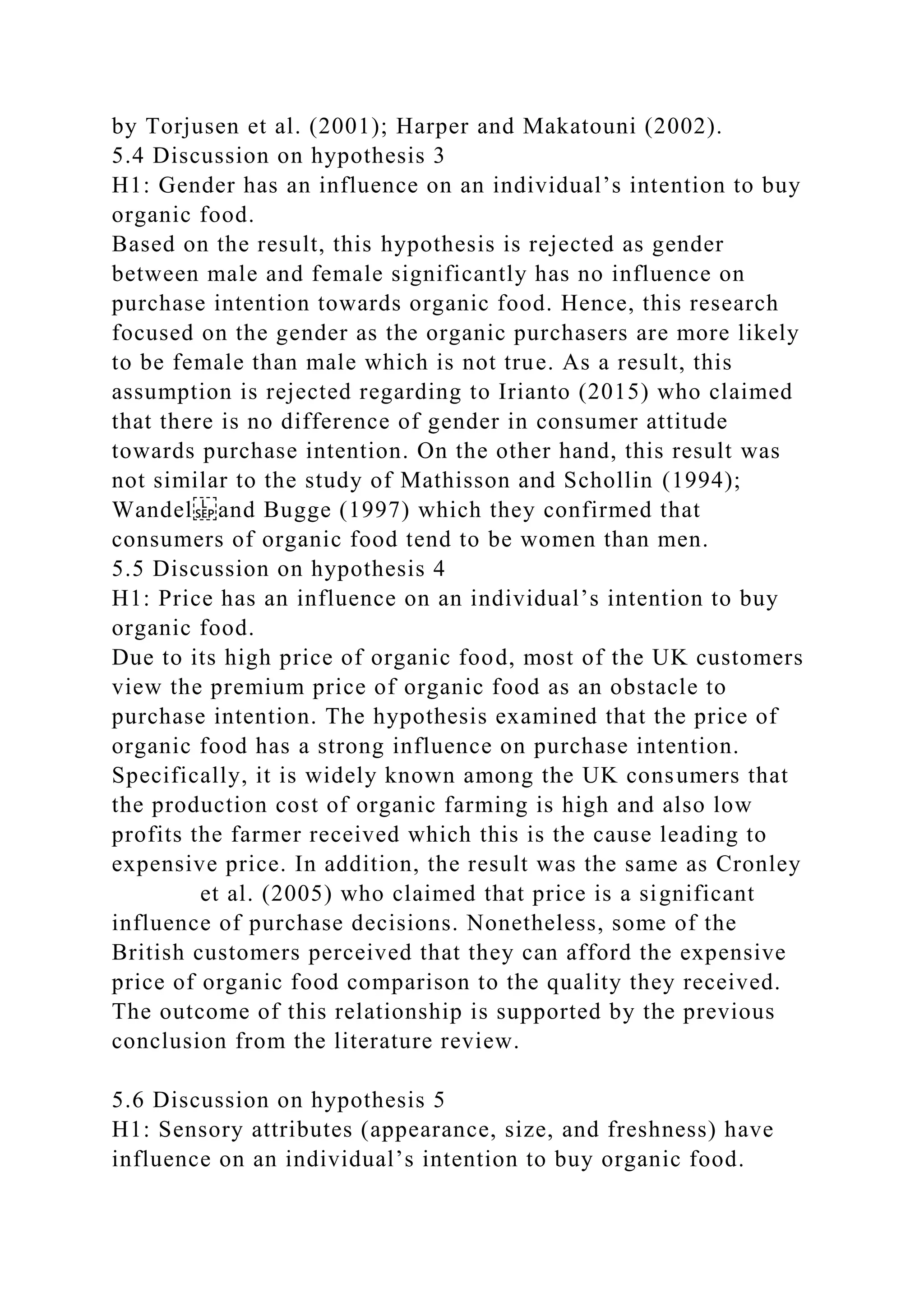

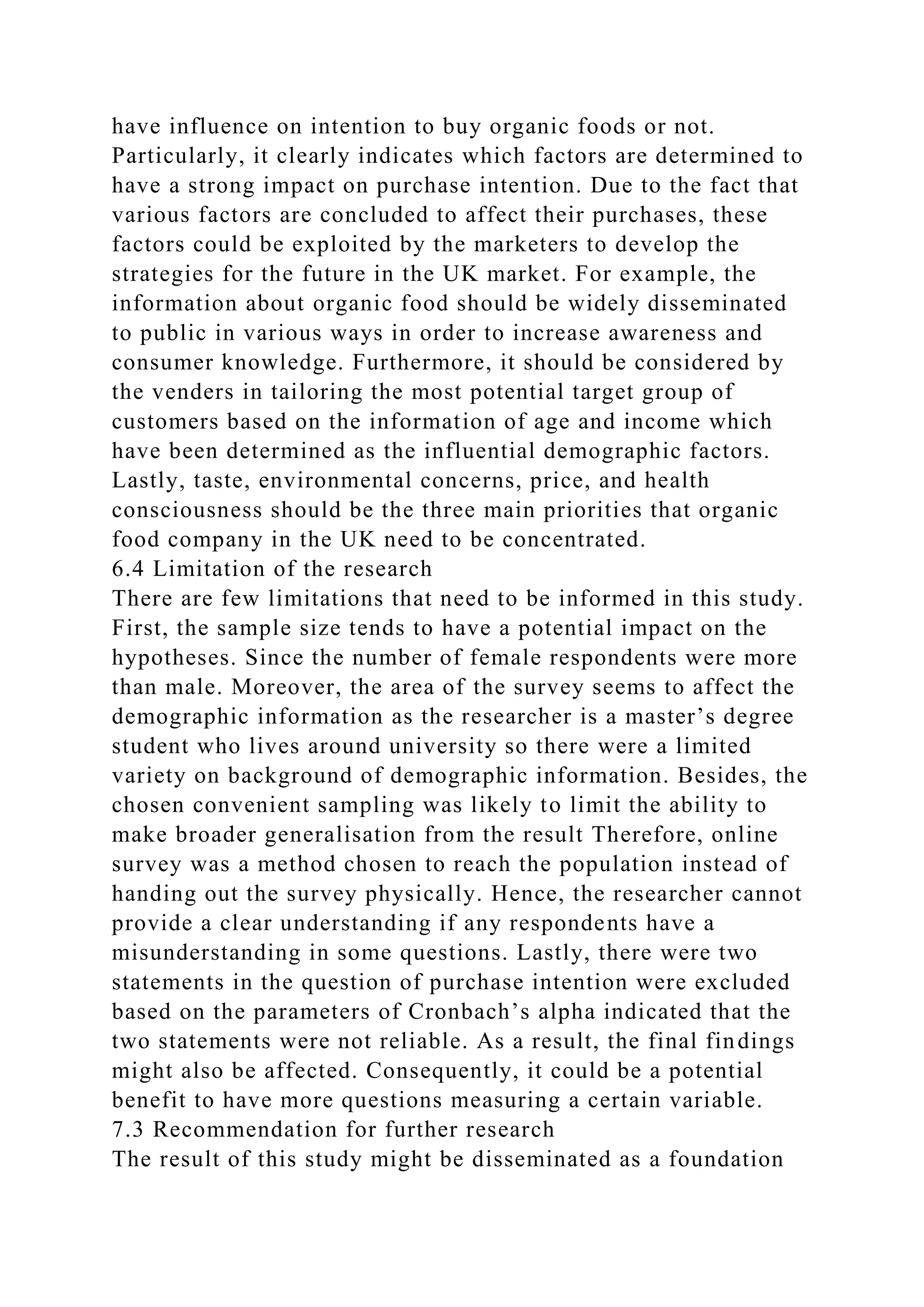

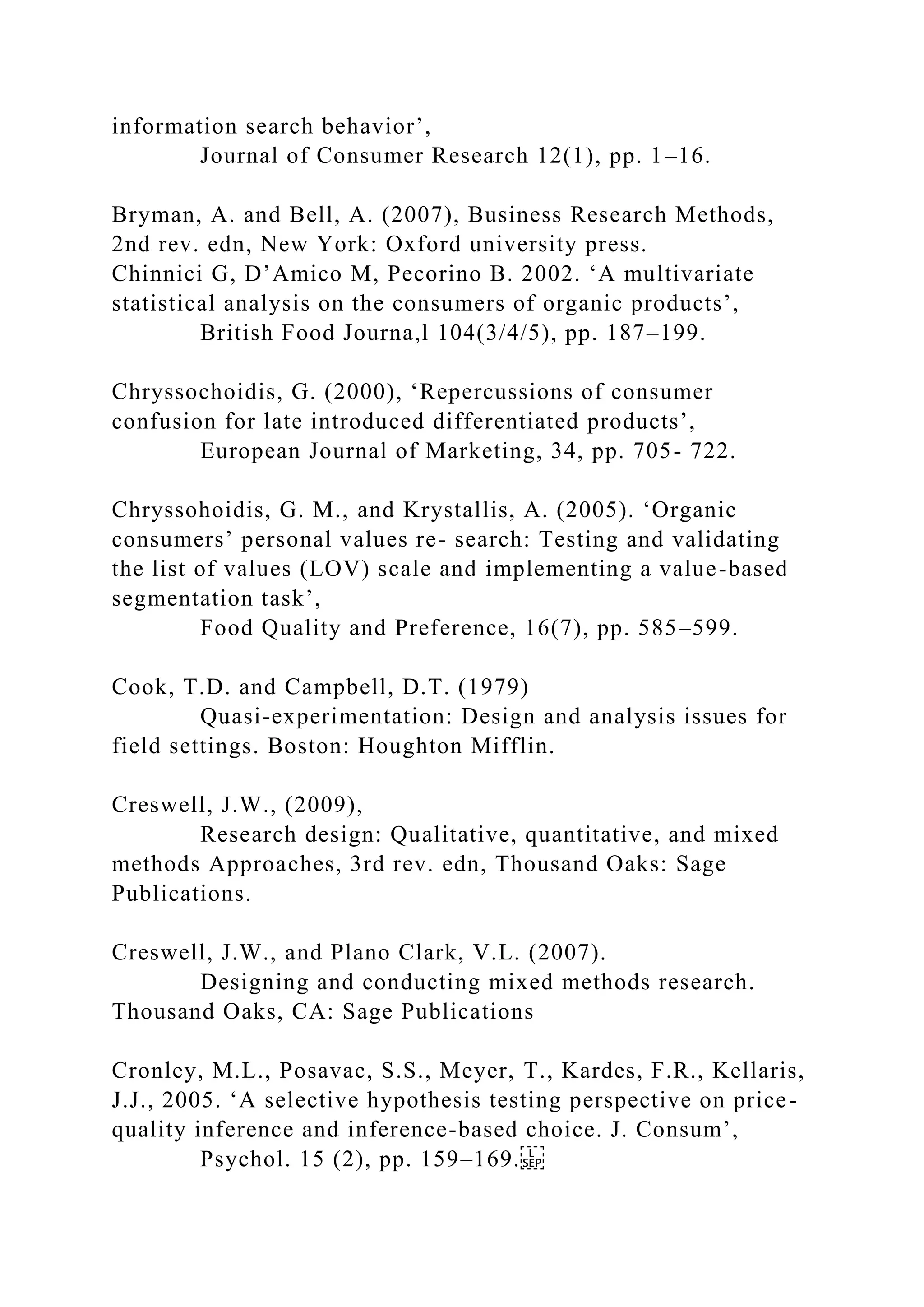

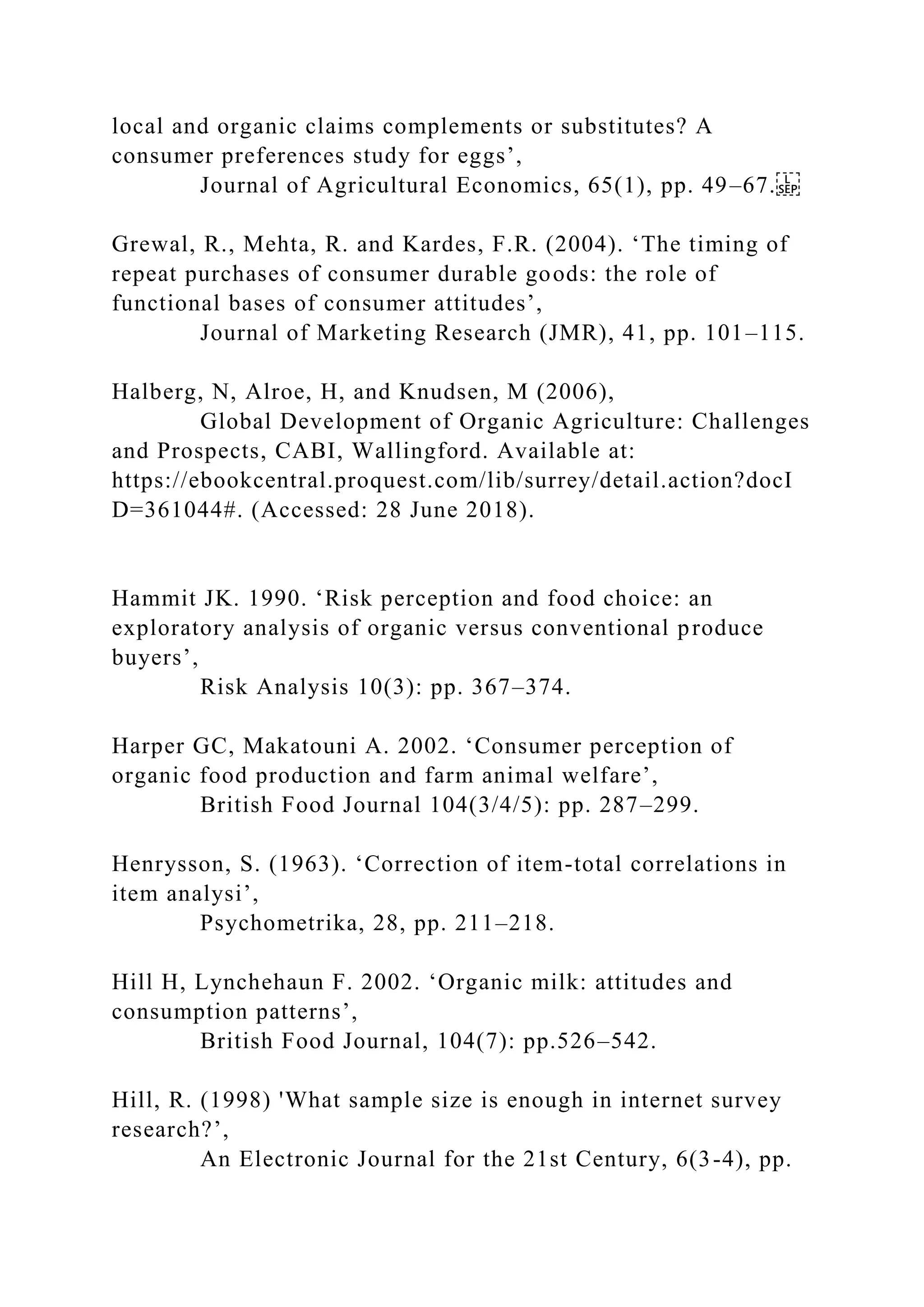

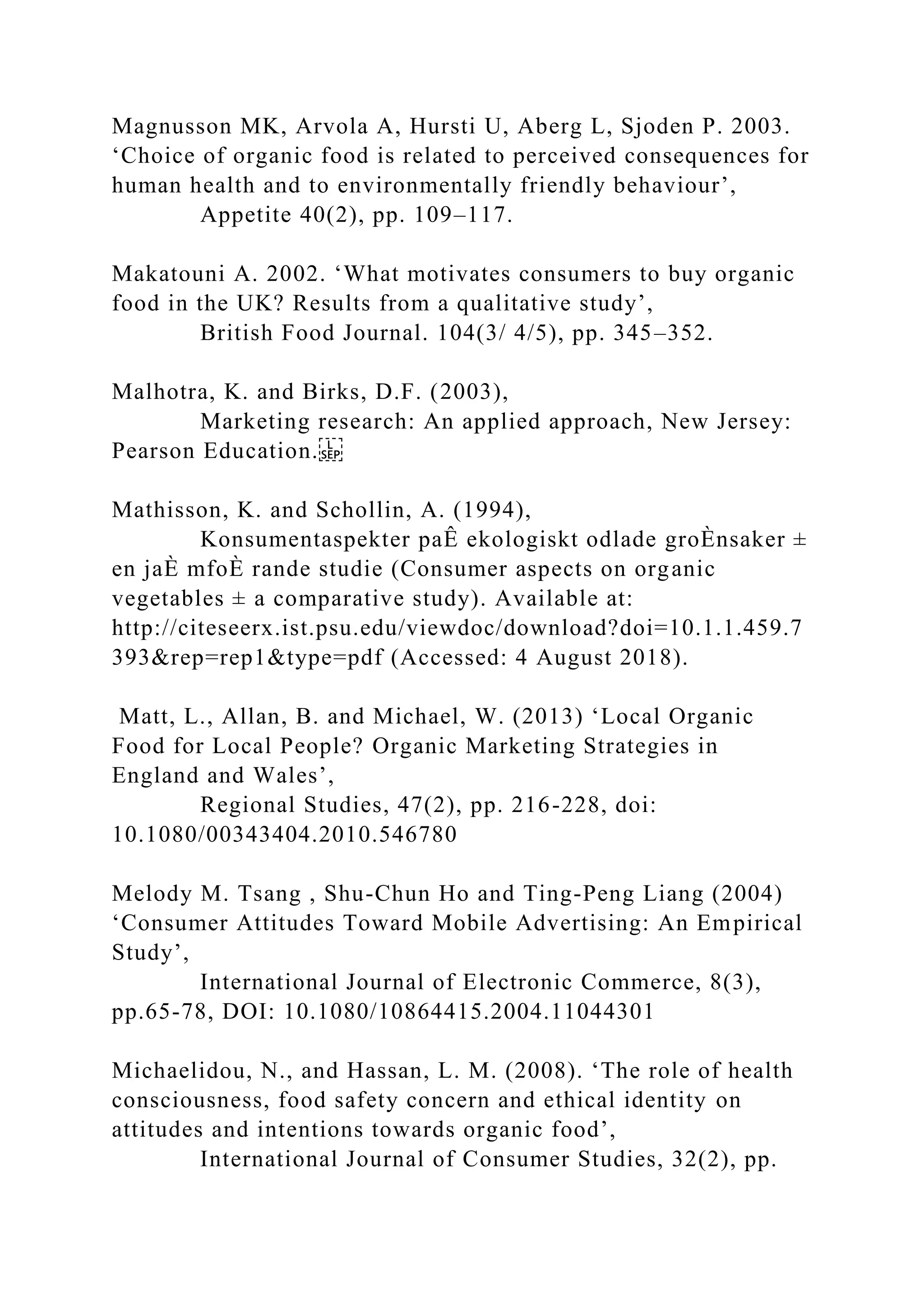

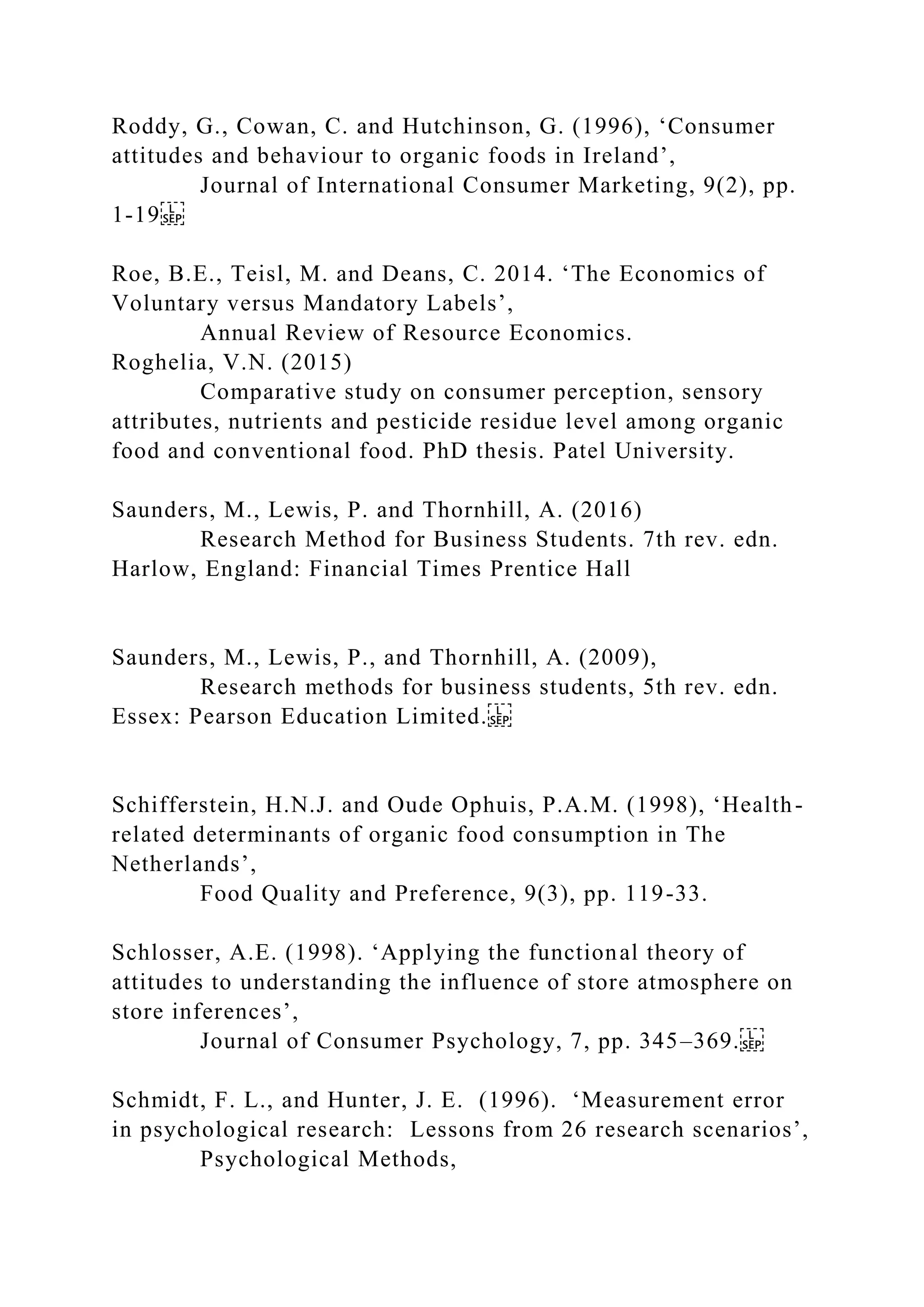

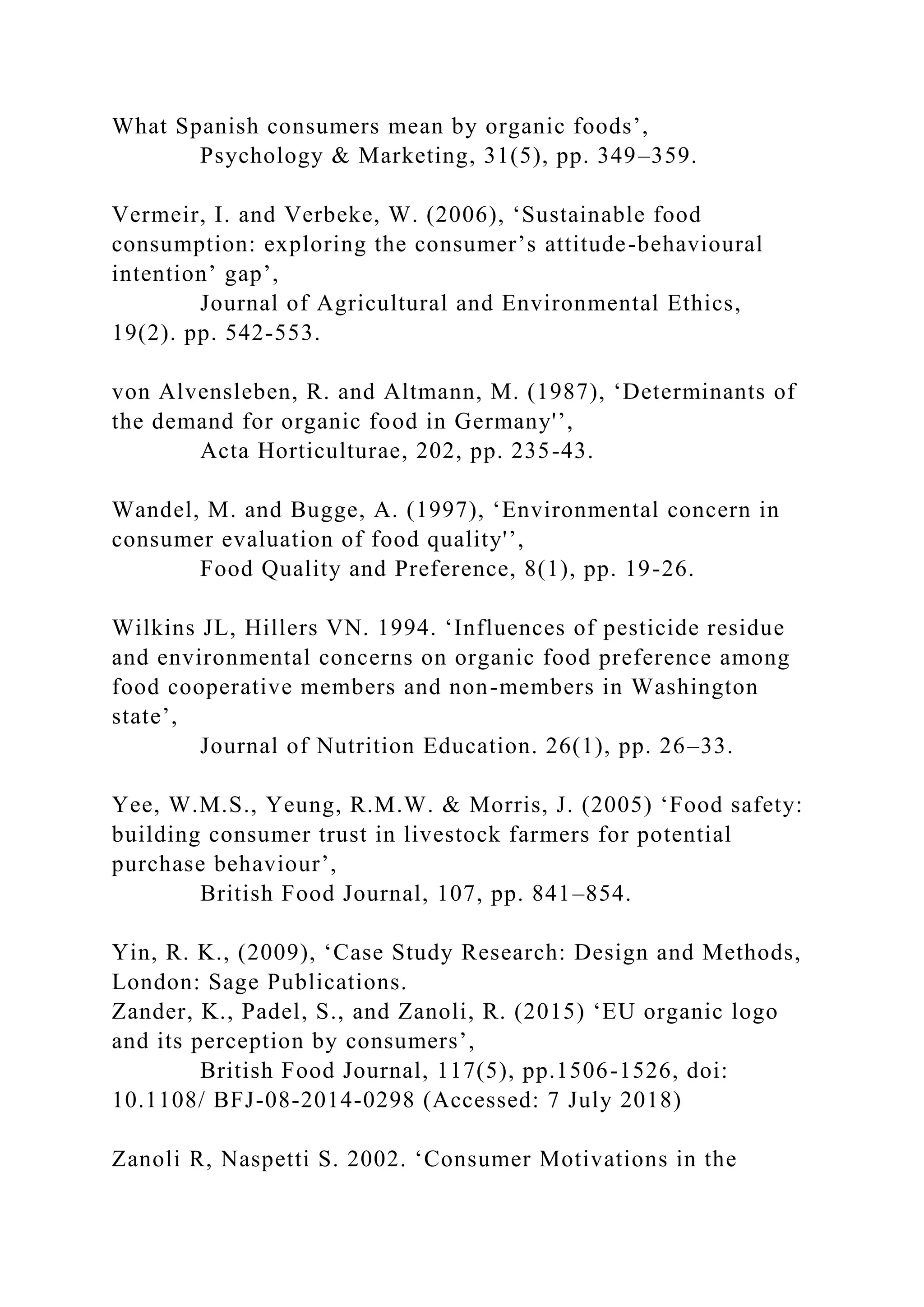

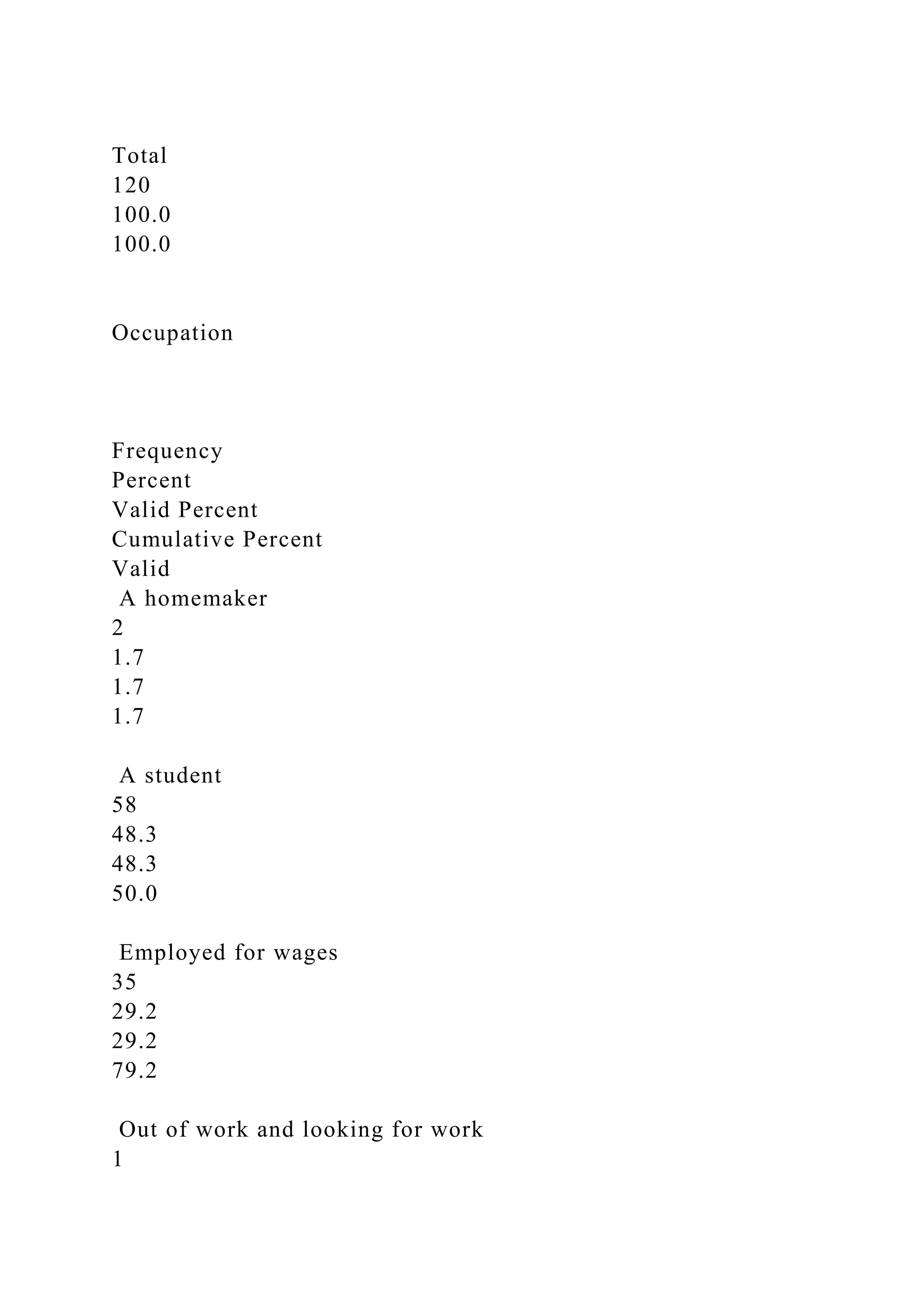

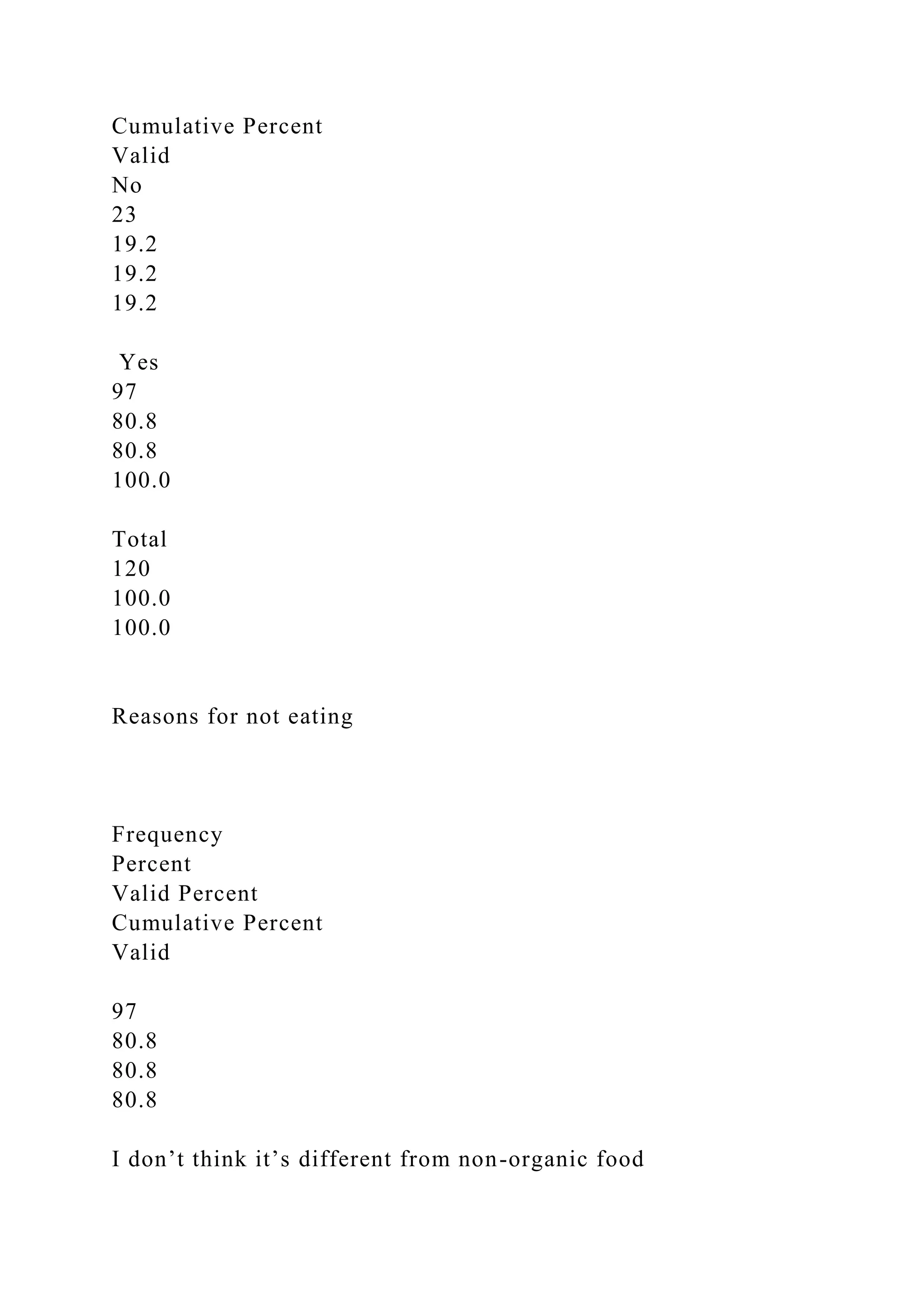

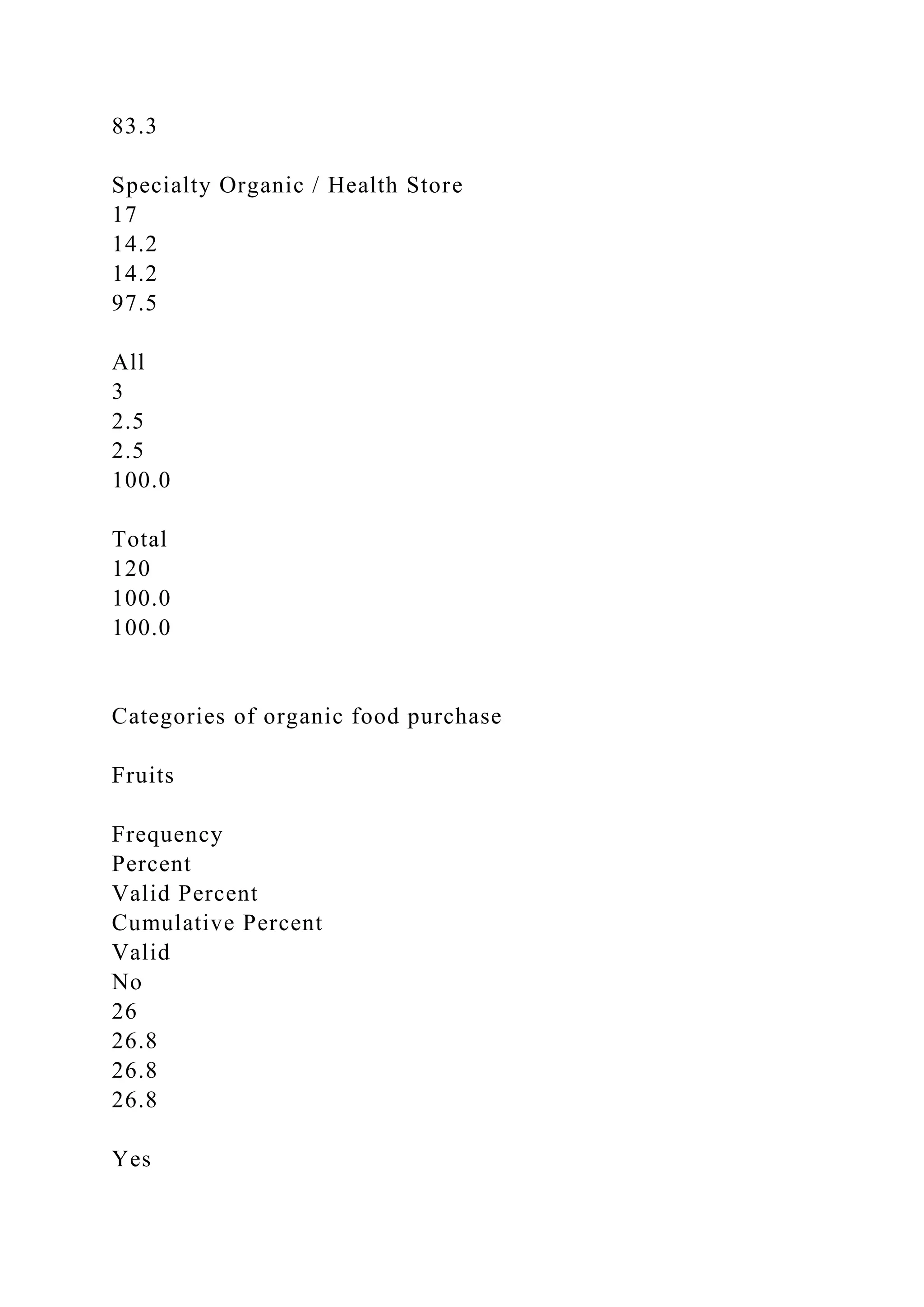

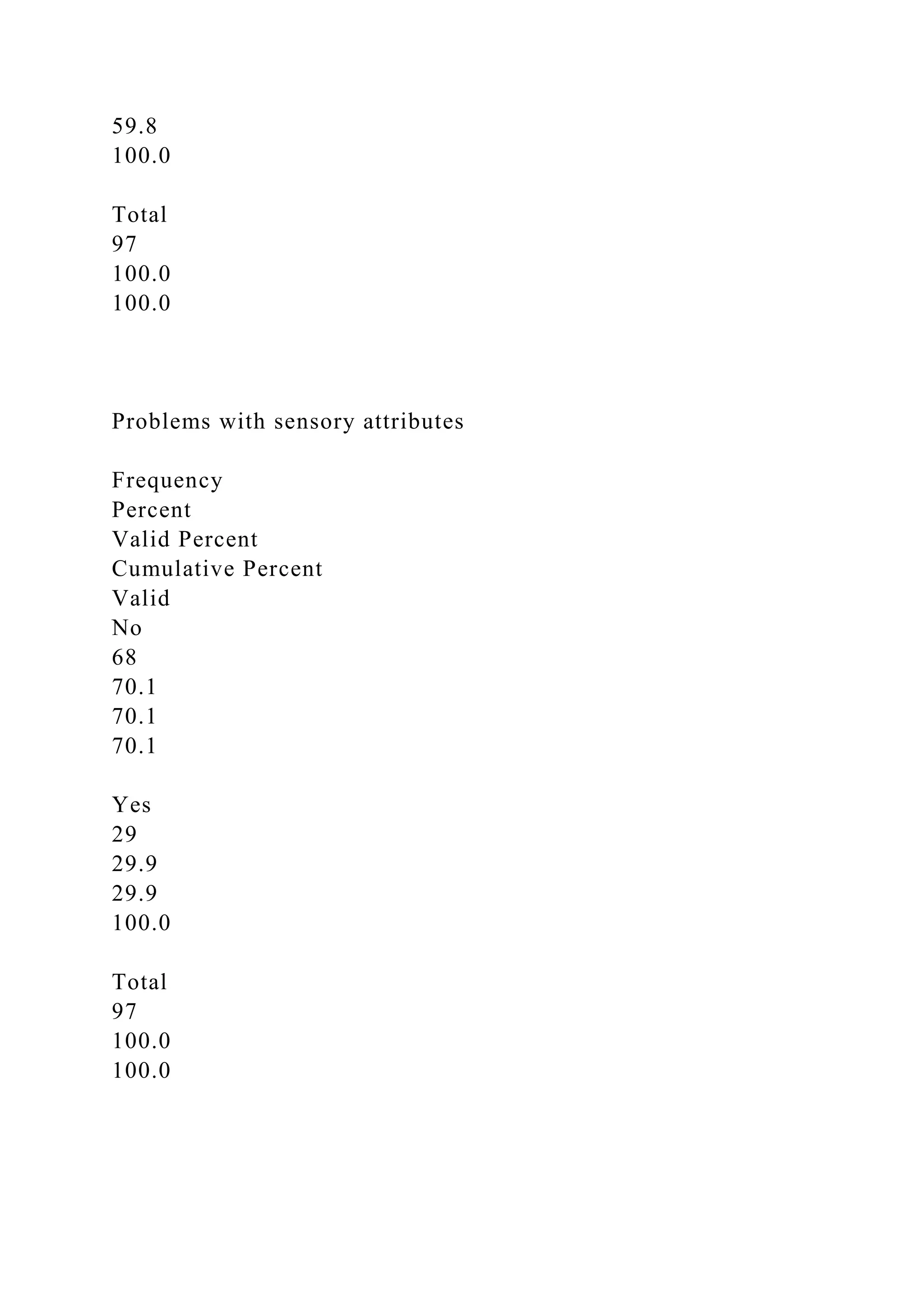

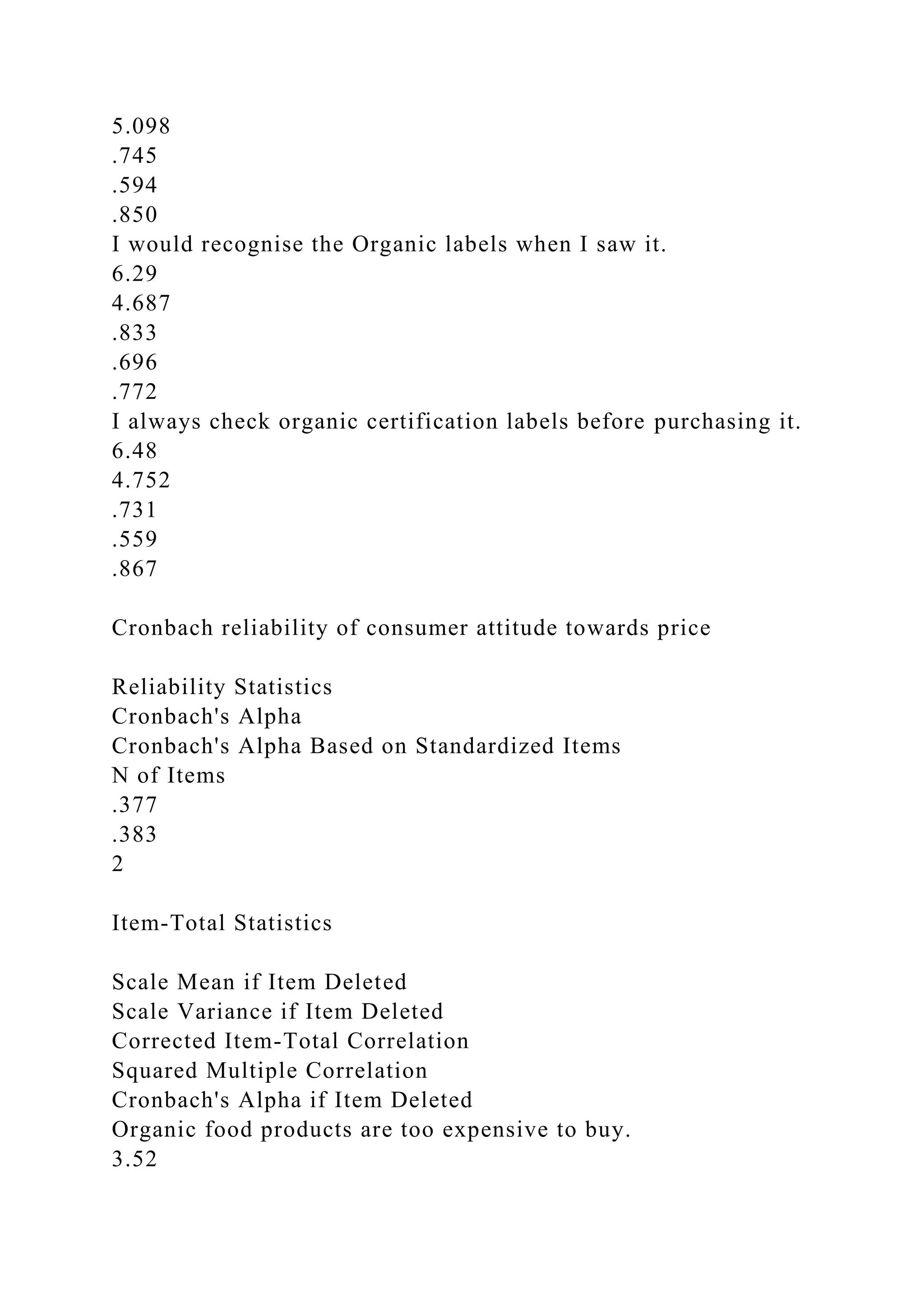

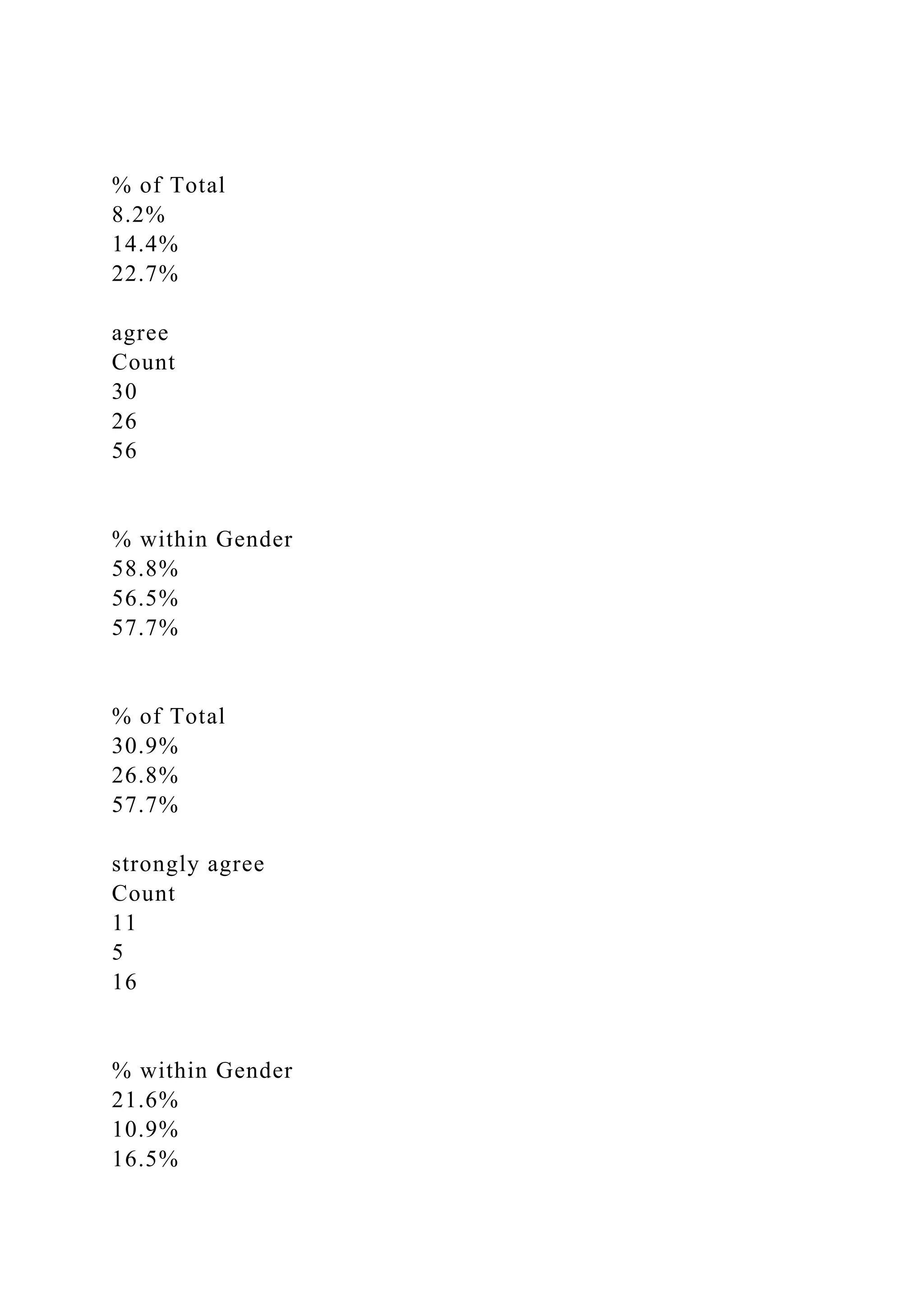

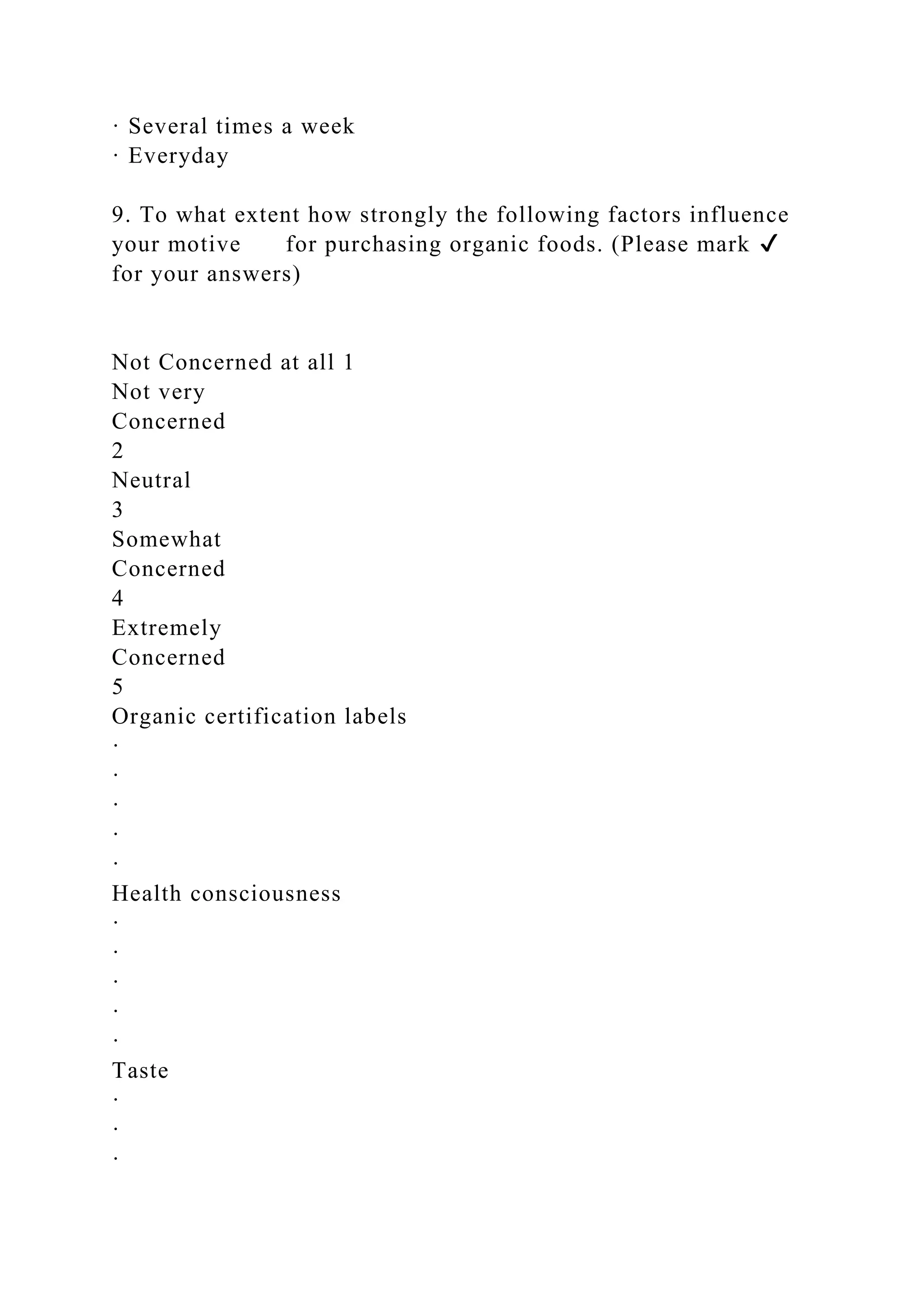

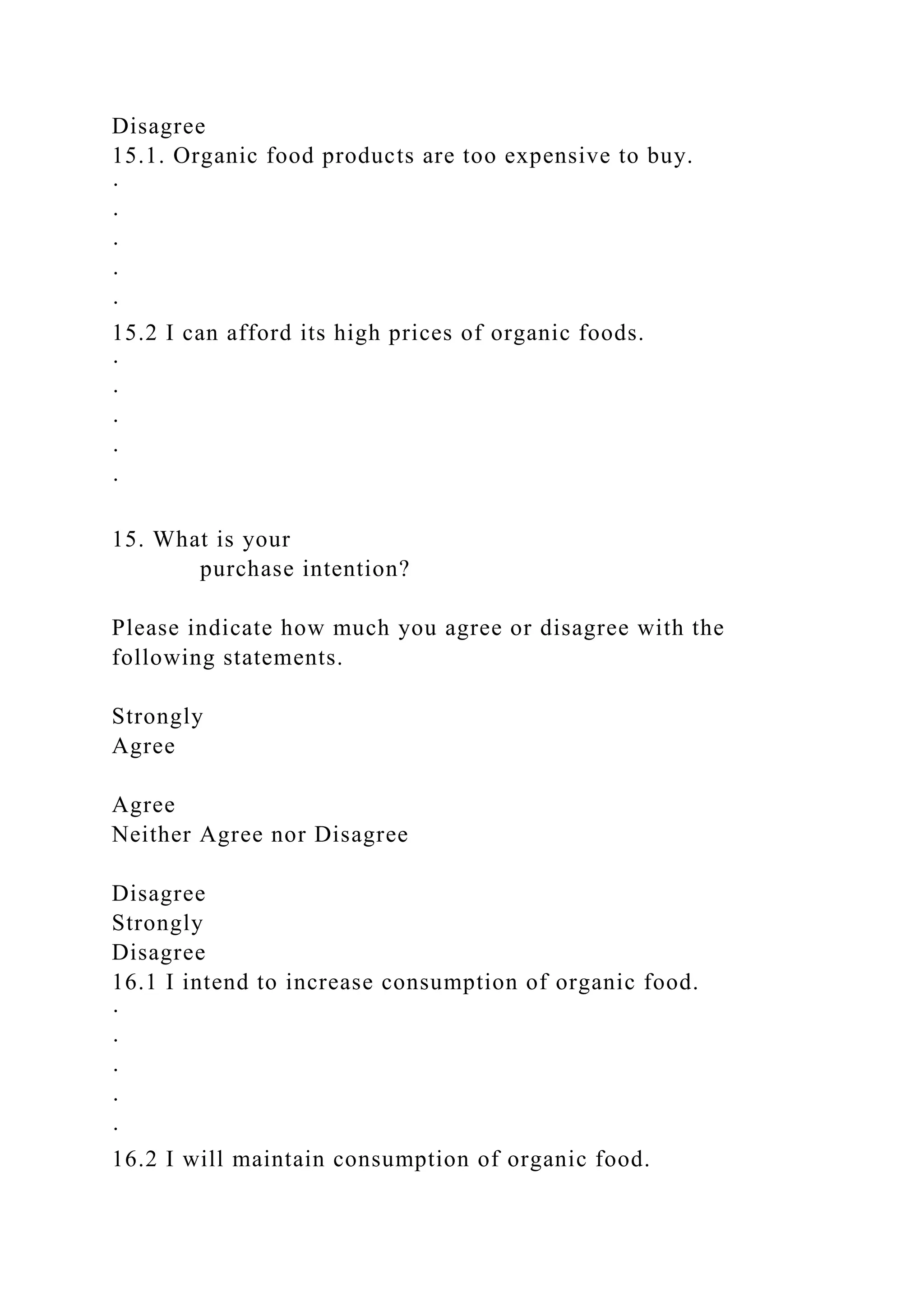

![Fruits Vegetables Poultry (Eggs) Red Meat 73.2 92.8

39.2 27.8

Where do you usually buy organic food? [VALUE]%

[VALUE]%

[VALUE]%

Generic Supermarket/ Retailer Producer/ FarmSpecialty

Organic/ Health store Others (all) 59.2 5.0 14.2 2.5

Challenges

Challenges

Limited variety Problems with sensory attributes Lack of

education about organic food Concerns about disease in

organic food Expensive Others (Never face any

challenges) 0.598 0.299 0.216 0.175 0.093

0.041

Consumer knowledge I know a lot I know something I

know nothing 15.0 63.3 2.5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/submittedinpartfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof-230119024927-31555ff9/75/Submitted-in-part-fulfilment-of-the-requirements-for-the-degree-of-docx-150-2048.jpg)

![image3.png

image4.png

image5.png

image6.png

image7.png

image8.png

image9.png

image10.png

image11.png

image12.png

image13.png

image14.png

image15.png

image16.png

image1.png

image2.png

MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

DISSERTATION PROPOSAL FORM

Name : Amonwan Thongkamkhao

Student ID: 22427988

Contact Details (E-Mail/Telephone No.) : [email protected]

Main DiscipLINE of Dissertation (

Please tick one only as the most appropriate.):

Organizational Behavior

HRM

Financial Decision Making

Business Negotiation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/submittedinpartfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof-230119024927-31555ff9/75/Submitted-in-part-fulfilment-of-the-requirements-for-the-degree-of-docx-151-2048.jpg)