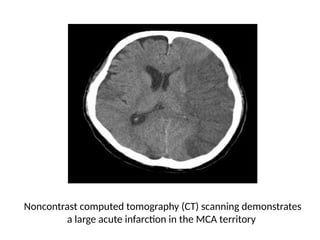

The document reviews the management of stroke, detailing definitions, epidemiology, anatomy, classification, evaluation, and management strategies. Stroke, defined as a rapidly developing disturbance of cerebral function, is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide, with ischemic strokes being more common than hemorrhagic ones. The text emphasizes the importance of timely diagnosis and intervention to improve patient outcomes, including details on essential monitoring, glycemic control, and supportive care during the acute and sub-acute phases.