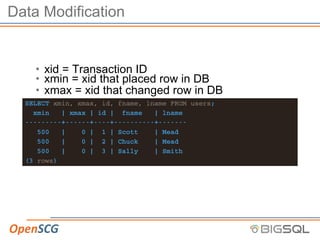

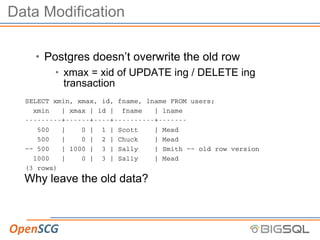

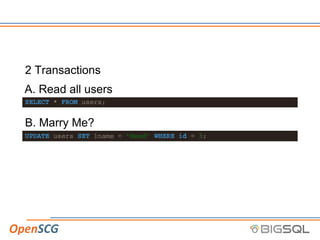

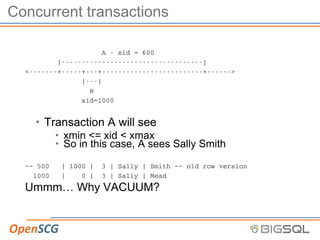

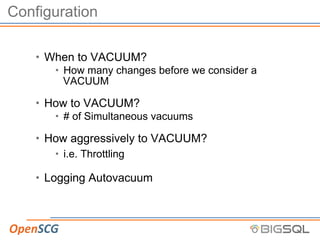

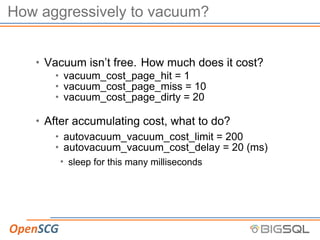

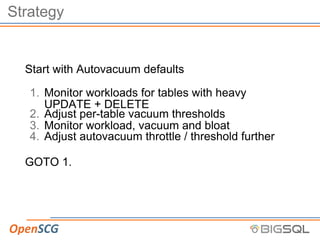

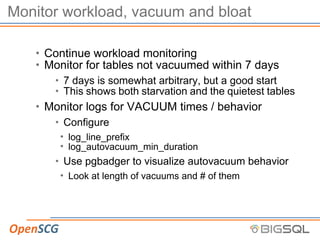

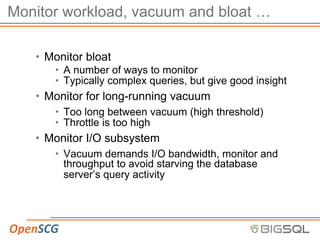

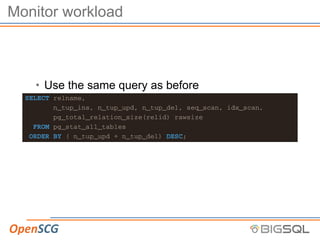

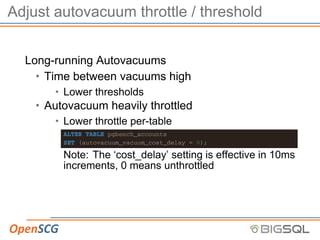

The document discusses strategic autovacuum configuration and monitoring in PostgreSQL. It begins by explaining the ACID properties and how MVCC and transactions work. It then discusses how to monitor workloads for heavily updated tables, adjust per-table autovacuum thresholds to prioritize those tables, monitor autovacuum behavior over time using logs and queries, and tune the autovacuum throttle settings based on that monitoring to optimize autovacuum performance. The key steps are to start with defaults, monitor workload changes, adjust settings for busy tables, continue monitoring, and refine settings as needed.