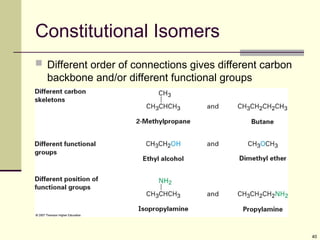

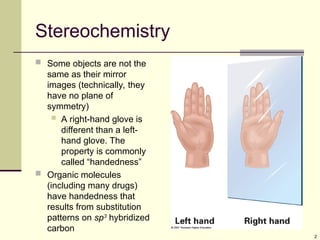

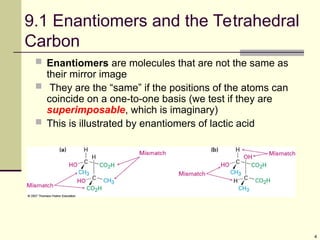

Explain in details the Some objects are not the same as their mirror images (technically, they have no plane of symmetry)

A right-hand glove is different than a left-hand glove. The property is commonly called “handedness”

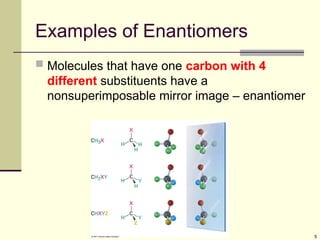

Organic molecules (including many drugs) have handedness that results from substitution patterns on sp3 hybridized carbon

![12

Optical Activity

Light passes through a plane polarizer

Plane polarized light is rotated in solutions of optically

active compounds

Measured with polarimeter

Rotation, in degrees, is []

Clockwise rotation is called dextrorotatory

Anti-clockwise is levorotatory](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stereochemistry1-250610134630-9224ea2c/85/STEREOCHEMISTRY-1-for-year-2-stdents-ppt-12-320.jpg)

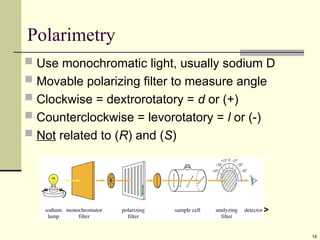

![15

Specific Rotation

To have a basis for comparison, define specific

rotation, []D for an optically active compound

[]D = observed rotation/(pathlength x concentration)

= /(l x C) = degrees/(dm x g/mL)

Specific rotation is that observed for 1 g/mL in

solution in cell with a 10 cm path using light from

sodium metal vapor (589 nm)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stereochemistry1-250610134630-9224ea2c/85/STEREOCHEMISTRY-1-for-year-2-stdents-ppt-15-320.jpg)