1. The study examined the relationship between emotional-behavioral traits and rhythm imitation performance in 100 5th grade elementary school students.

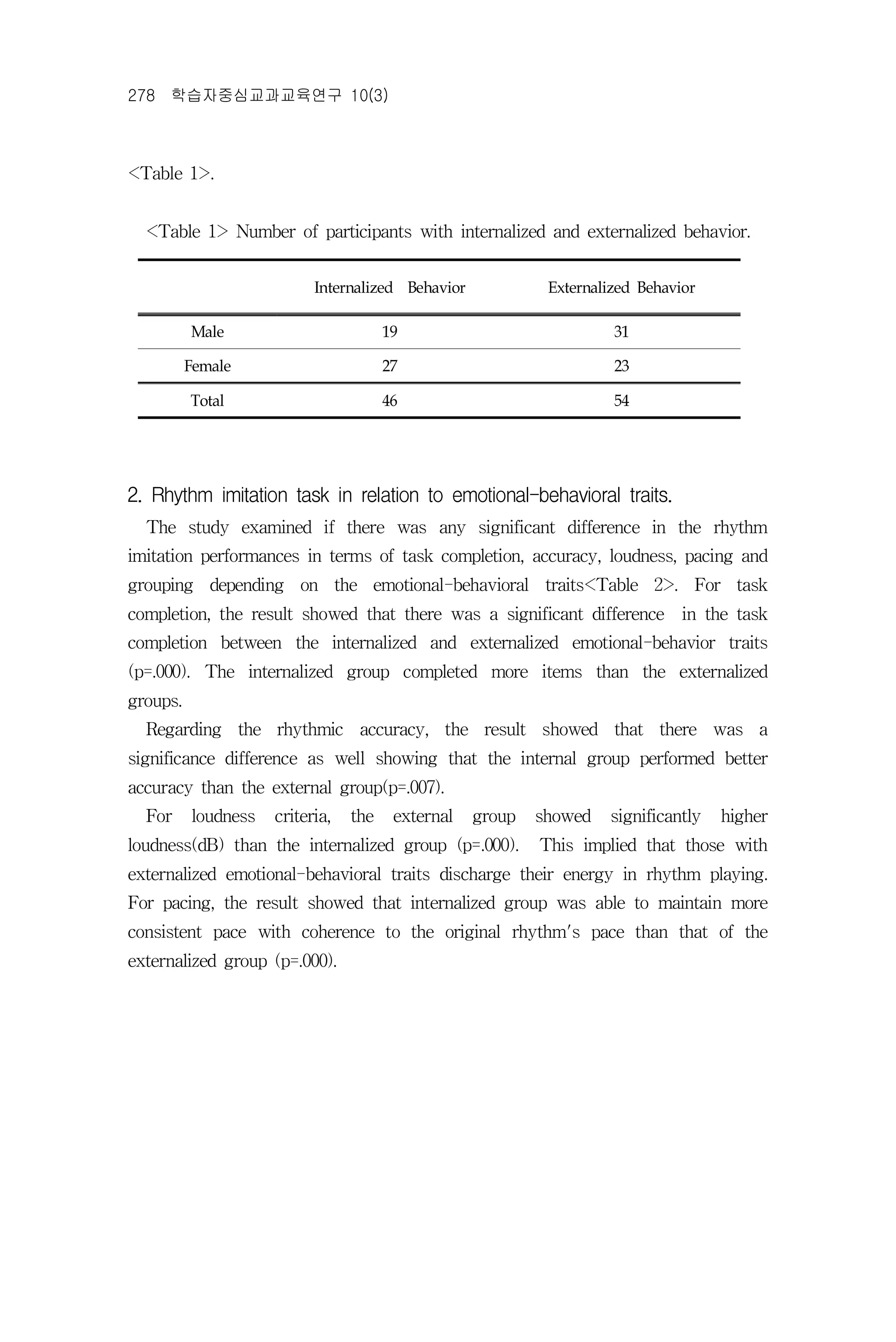

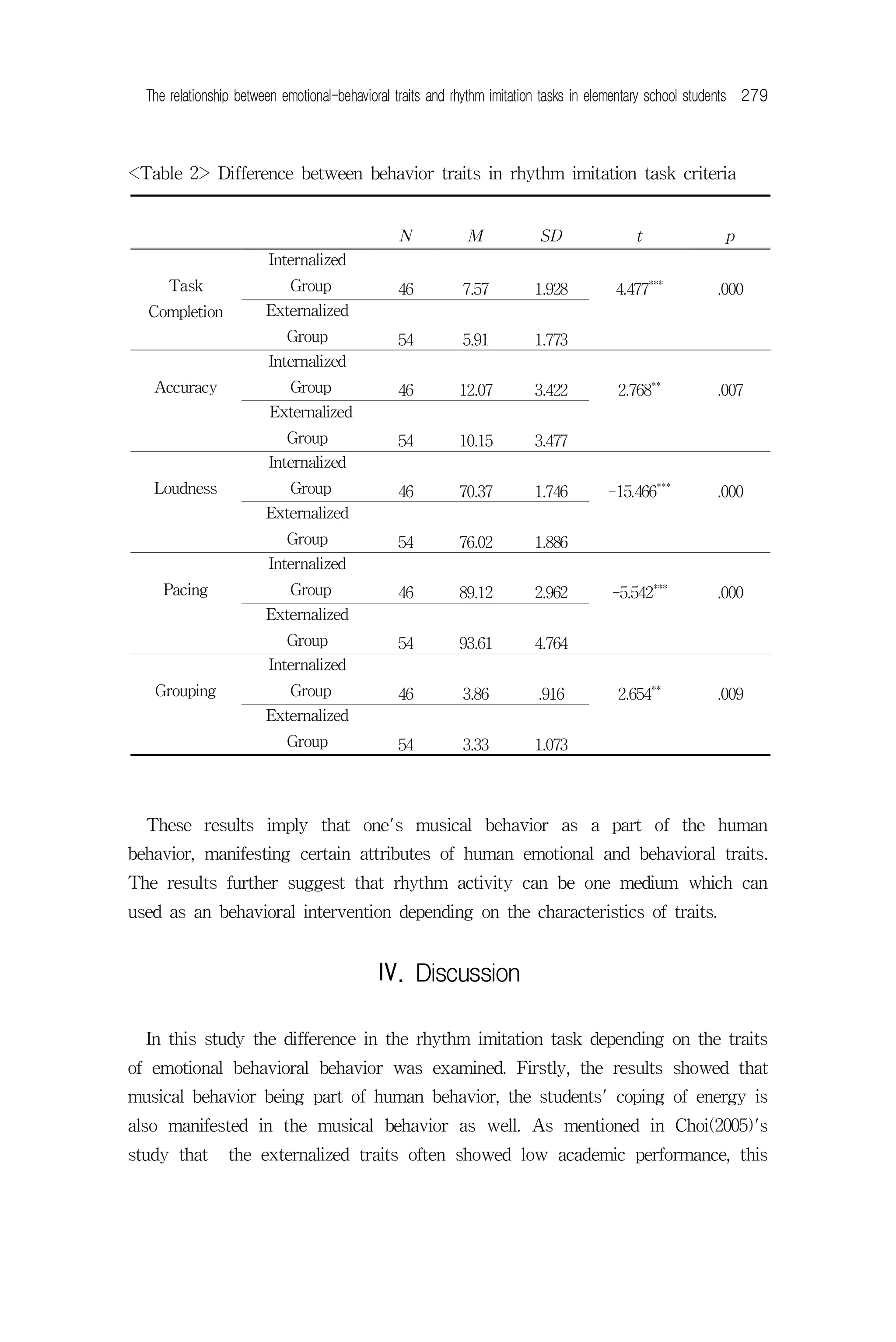

2. Students were assessed for internalizing vs. externalizing emotional-behavioral traits using standardized tests. They then completed rhythm imitation tasks that were analyzed based on completion, accuracy, intensity, pace, and grouping.

3. The results showed significant differences between students with internalizing vs. externalizing traits in task completion, accuracy, intensity, and pace, suggesting rhythm performance reflects one's emotional and behavioral characteristics.