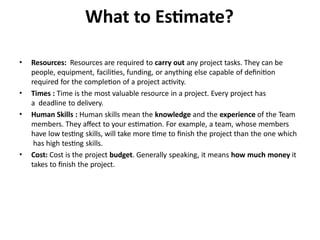

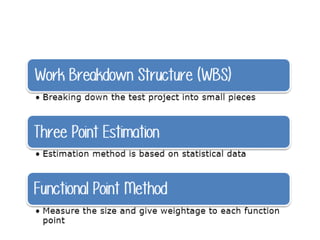

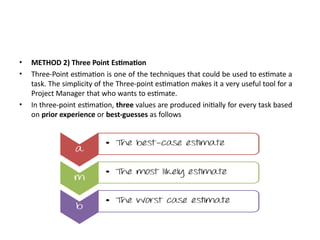

The software testing life cycle (STLC) consists of specific activities aimed at ensuring software quality and includes planning, execution, and reporting. Important aspects discussed are test independence, test management roles, and estimation techniques, which influence the effectiveness and efficiency of testing processes. Additionally, risks associated with testing, both product and project-related, are evaluated to guide planning and execution towards maintaining quality standards.