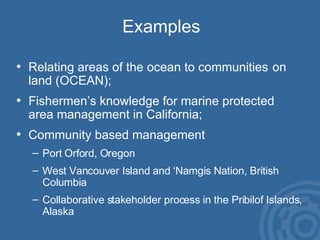

This document discusses the importance of considering socioeconomic factors in marine resource management. It provides an overview of tools from social sciences that can be used, such as interviews, surveys and participatory research. Examples are given of projects that incorporated local ecological knowledge from fishermen into marine protected area planning in California. Additional examples describe community-based management approaches in Port Orford, Oregon and among First Nations groups in western Vancouver Island, Canada that engaged local stakeholders in fisheries management. The conclusion emphasizes that laws like the Magnuson-Stevens Act require socioeconomic impacts to communities be addressed alongside environmental concerns in management.