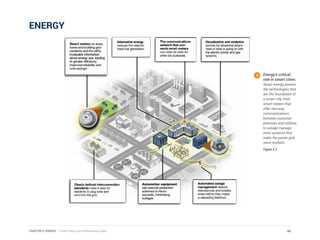

The document is a planning manual for building smart cities. It defines a smart city as one that uses information and communication technologies to enhance livability, workability and sustainability. A smart city collects data from sensors around the city, communicates that data through wired and wireless networks, and analyzes the data to understand current conditions and predict future needs in order to improve operations and decision making. The document provides guidance to help cities develop their own roadmaps for becoming smarter through the use of emerging technologies.

![Energy-efficient equipment is only part of the solution. “You also need

to make intelligent decisions about equipment settings, and that

requires gathering and analyzing information from disparate building

systems, including metering systems and PDUs [power distribution

units],” says David Shroyer, a NetApp controls engineer.

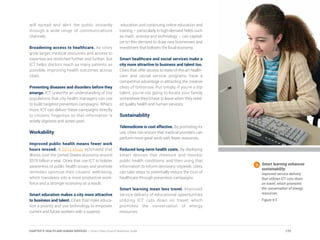

To aid that effort the company deployed the Network Building Mediator

from Council member Cisco, which aggregates information from all of

NetApp’s building systems, including lighting, heating, ventilation, air

conditioning, temperature sensors and PDUs, from multiple vendors.

Building engineers and facilities personnel can control systems in any

building using a web-based interface. Demand response payments

from PG&E paid for the system and NetApp has since deployed

Network Building Mediator for automated demand response at its prop-

erties in Europe and India.

“Within 20 minutes of the demand-response signal from the utility, the

Cisco Network Building Mediator reduces lighting by 50 percent and rais-

es the temperature set point by four degrees, shedding 1.1 megawatts.”

Facility helps public and private

sector researchers scale up clean

energy technologies

Located at the National Renewable Energy

Laboratory’s campus in Golden, Colorado, the

new 182,500-square-foot Energy Systems

Integration Facility (ESIF) is the first facility in

the United States to help both public and

private sector researchers scale-up promising

clean energy technologies – from solar

modules and wind turbines to electric vehicles

and efficient, interactive home appliances –

and test how they interact with each other and

the grid at utility-scale. The U.S. Congress

provided $135 million to construct and equip

the facility.

ESIF, which opened in 2013, houses more

than 15 experimental laboratories and several

outdoor test beds, including an interactive

hardware-in-the-loop system that lets

researchers and manufacturers test their

products at full power and real grid load levels.

The facility will also feature a petascale super-

computer that can support large-scale model-

ing and simulation at one quadrillion opera-

tions per second.

Figure 5.18

104CHAPTER 5: ENERGY | Smart Cities Council Readiness Guide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/d7472b46-afb9-4d42-bf19-8cf321d43be5-160625105711/85/SmartCitiesCouncil-READINESSGUIDEV1-5-7-17-14-104-320.jpg)

![Enel is a multinational group based in Italy, a

leading integrated player in the power and gas

markets of Europe and Latin America, operat-

ing in 40 countries across 4 continents over-

seeing power generation from over 98 GW of

net installed capacity and distributing electrici-

ty and gas through a network spanning around

1.9 million km to serve approximately 61

million customers.

Enel was the first utility in the world to replace

the traditional electromechanical meters with

smart meters that make it possible to measure

consumption in real time and manage contrac-

tual relationships remotely. This innovative tool

is key to the development of smart grids,

smart cities and electric mobility.

Enel is strongly committed to renewable ener-

gy sources and to the research and develop-

ment of new environmentally friendly technol-

ogies. Enel Green Power [EGP] is the Group’s

publicly listed Company dedicated to the

growth and management of power generation

from renewable energy, operating around 8.7

GW of net installed capacity relying on hydro,

wind, geothermal, solar, biomass and

co-generation sources in Europe and the

Americas.

Enel on sustainability >

Enel on innovation >

Enel website >

Strongly committed to renewable

energy sources.

271APPENDIX | Smart Cities Council Readiness Guide](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/d7472b46-afb9-4d42-bf19-8cf321d43be5-160625105711/85/SmartCitiesCouncil-READINESSGUIDEV1-5-7-17-14-271-320.jpg)