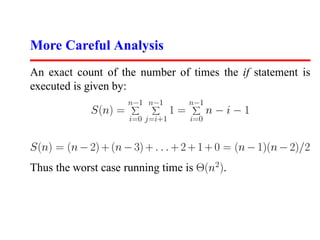

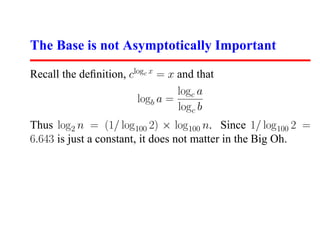

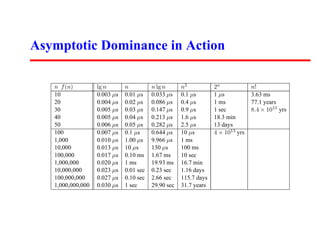

This document discusses program analysis and asymptotic analysis. It introduces asymptotic dominance hierarchies and uses examples like selection sort and binary search to analyze algorithms as Θ(n2), Θ(n log n), etc. Key concepts covered include logarithms, how they relate to trees, bits, and multiplication, and why the base of a logarithm is not important for asymptotic analysis.

![Selection Sort

selection sort(int s[], int n)

{

int i,j;

int min;

for (i=0; i<n; i++) {

min=i;

for (j=i+1; j<n; j++)

if (s[j] < s[min]) min=j;

swap(&s[i],&s[min]);

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/skienaalgorithm2007lecture03modelinglogarithms-111212074915-phpapp02/85/Skiena-algorithm-2007-lecture03-modeling-logarithms-10-320.jpg)