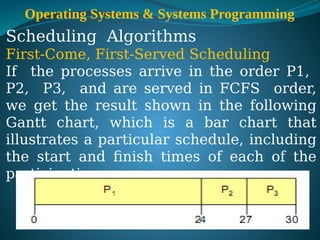

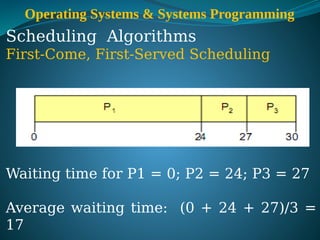

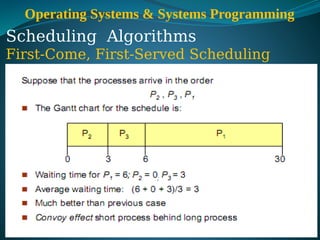

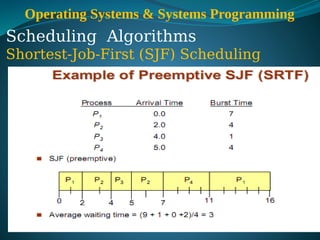

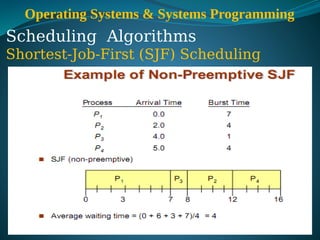

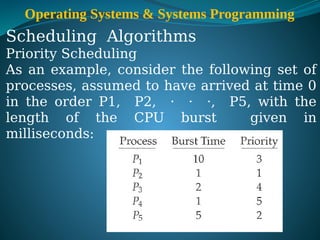

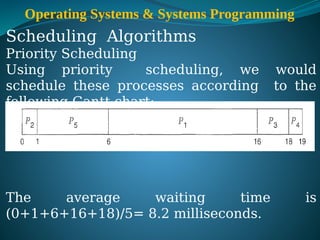

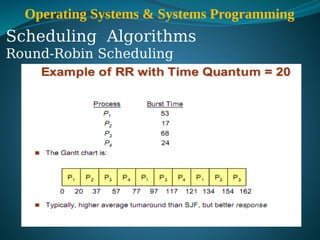

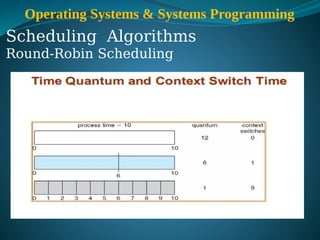

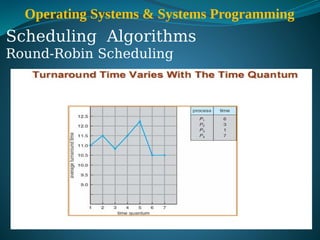

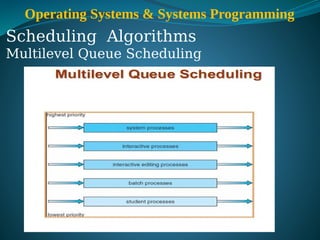

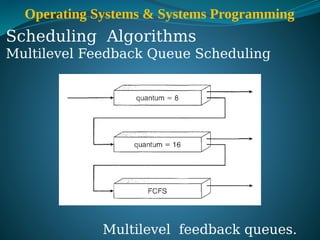

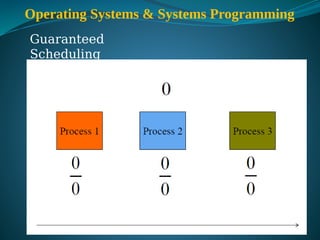

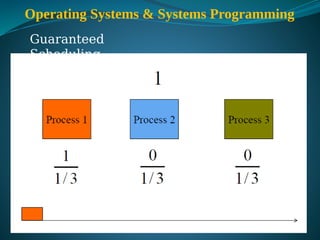

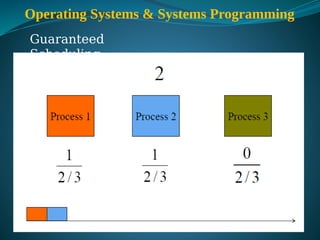

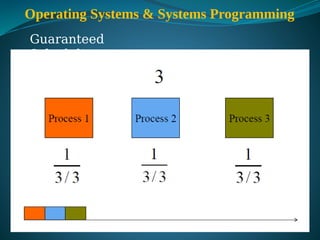

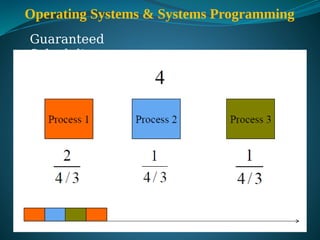

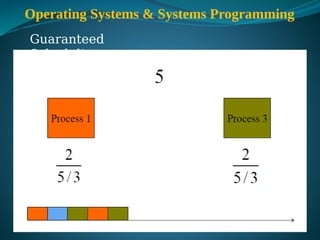

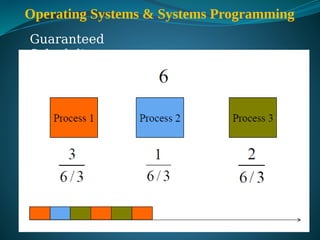

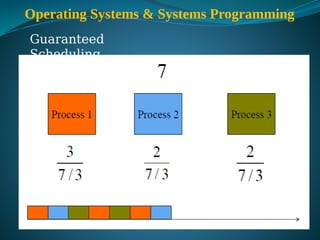

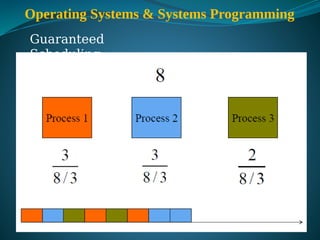

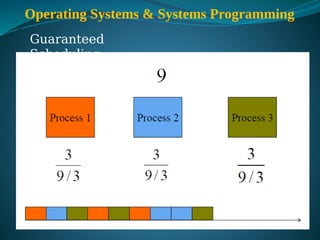

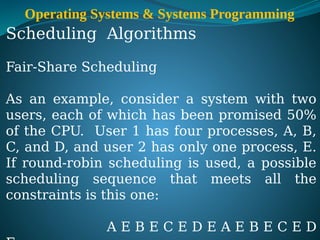

The document discusses various process scheduling algorithms used in operating systems, including first-come, first-served (FCFS), shortest job first (SJF), priority scheduling, round robin, multilevel queue scheduling, multilevel feedback queue scheduling, guaranteed scheduling, and lottery scheduling. It provides details on how each algorithm works, including examples and diagrams. Key aspects like preemptive vs. nonpreemptive, starvation prevention, and queue structure are explained for many of the algorithms.