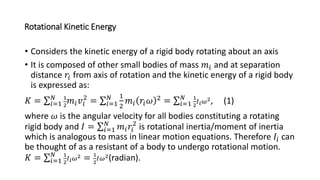

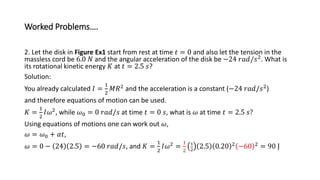

The document discusses rotational kinetic energy and rotational inertia. It defines rotational kinetic energy as 1/2Iω2, where I is the rotational inertia and ω is the angular velocity. Rotational inertia, analogous to mass in linear motion, is a measure of an object's resistance to changes in its rotational motion. It provides an example of calculating the rotational kinetic energy of a uniform disk rotating about a fixed axis, given its moment of inertia, angular acceleration, and time.