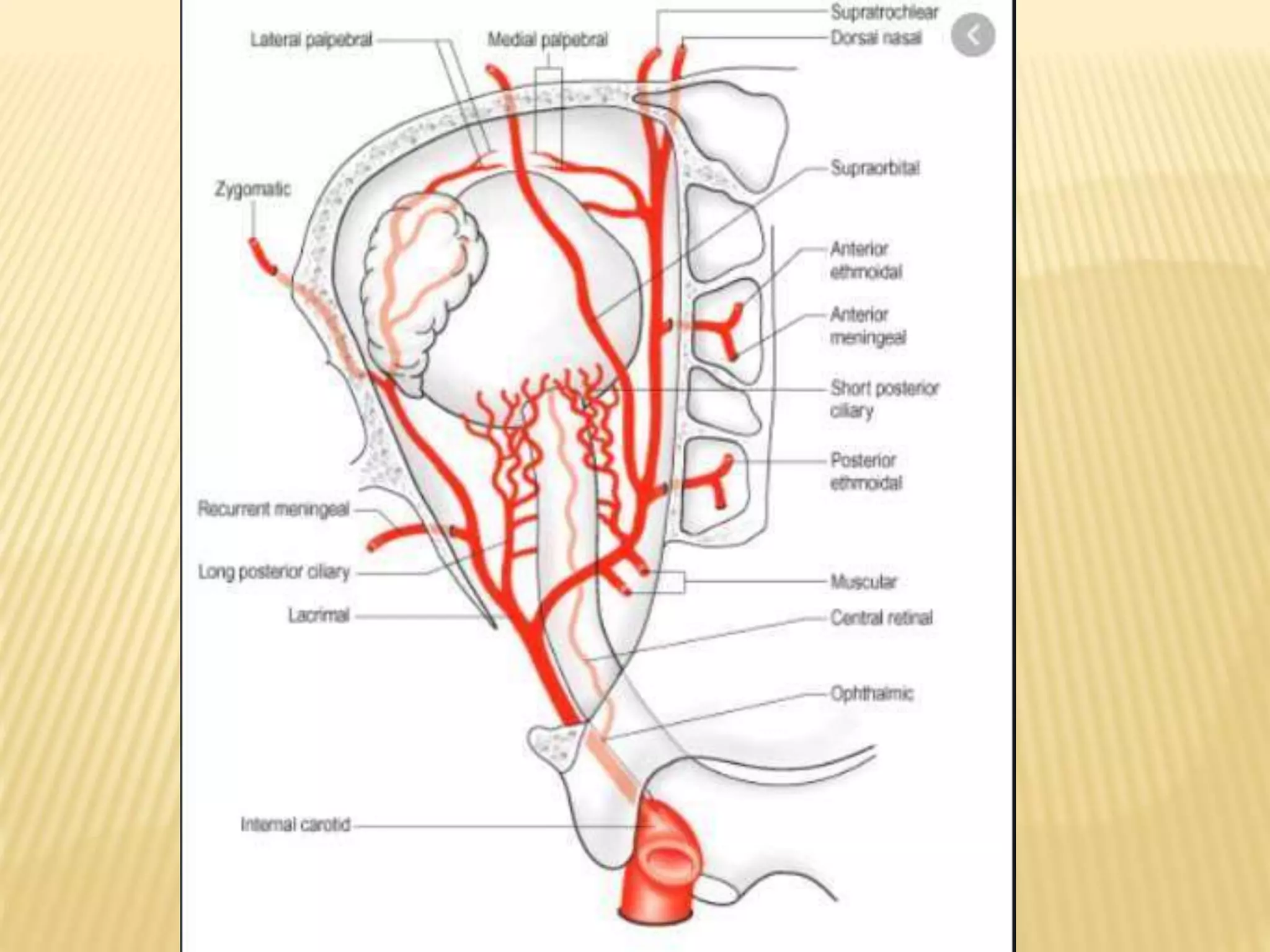

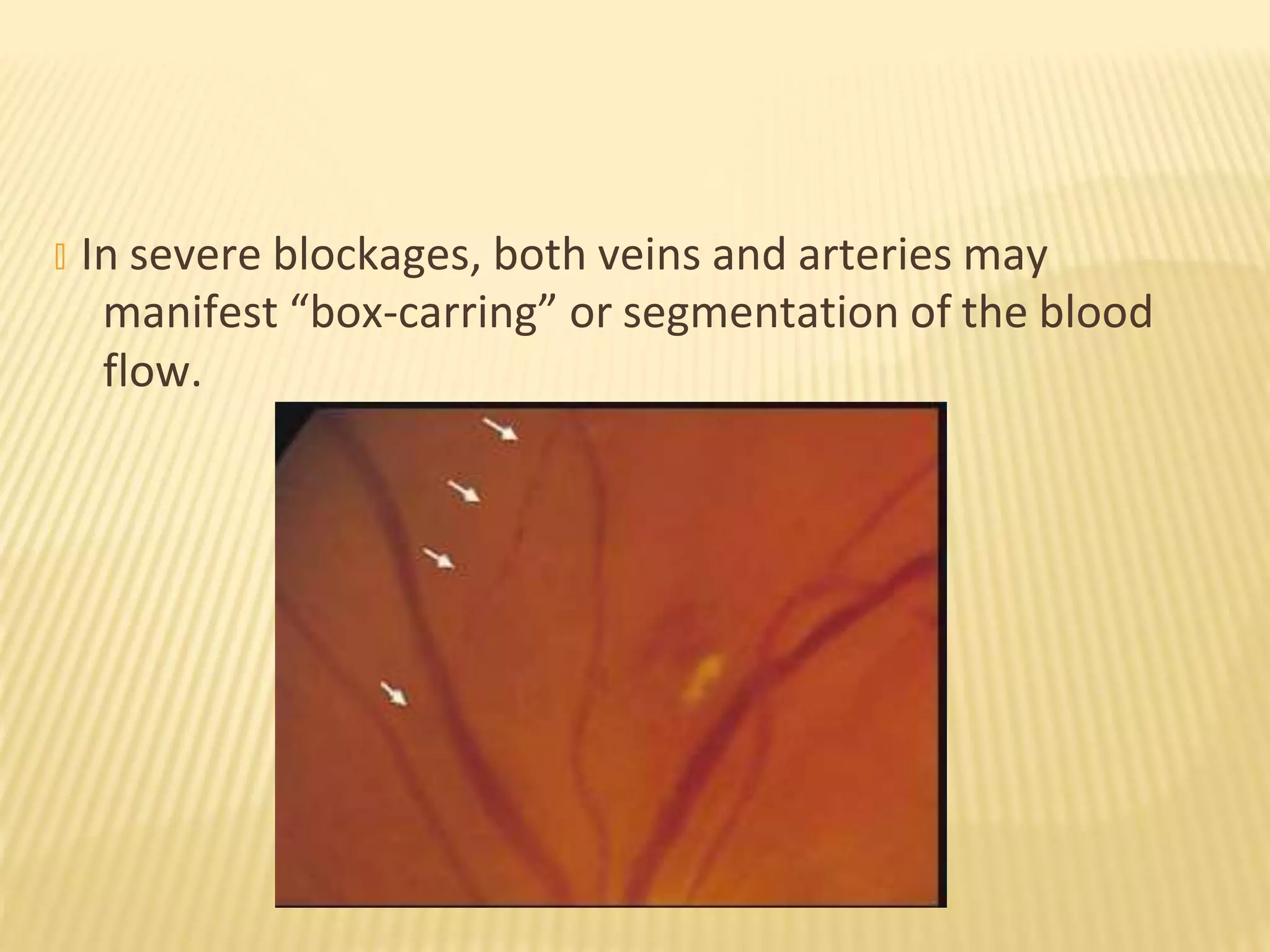

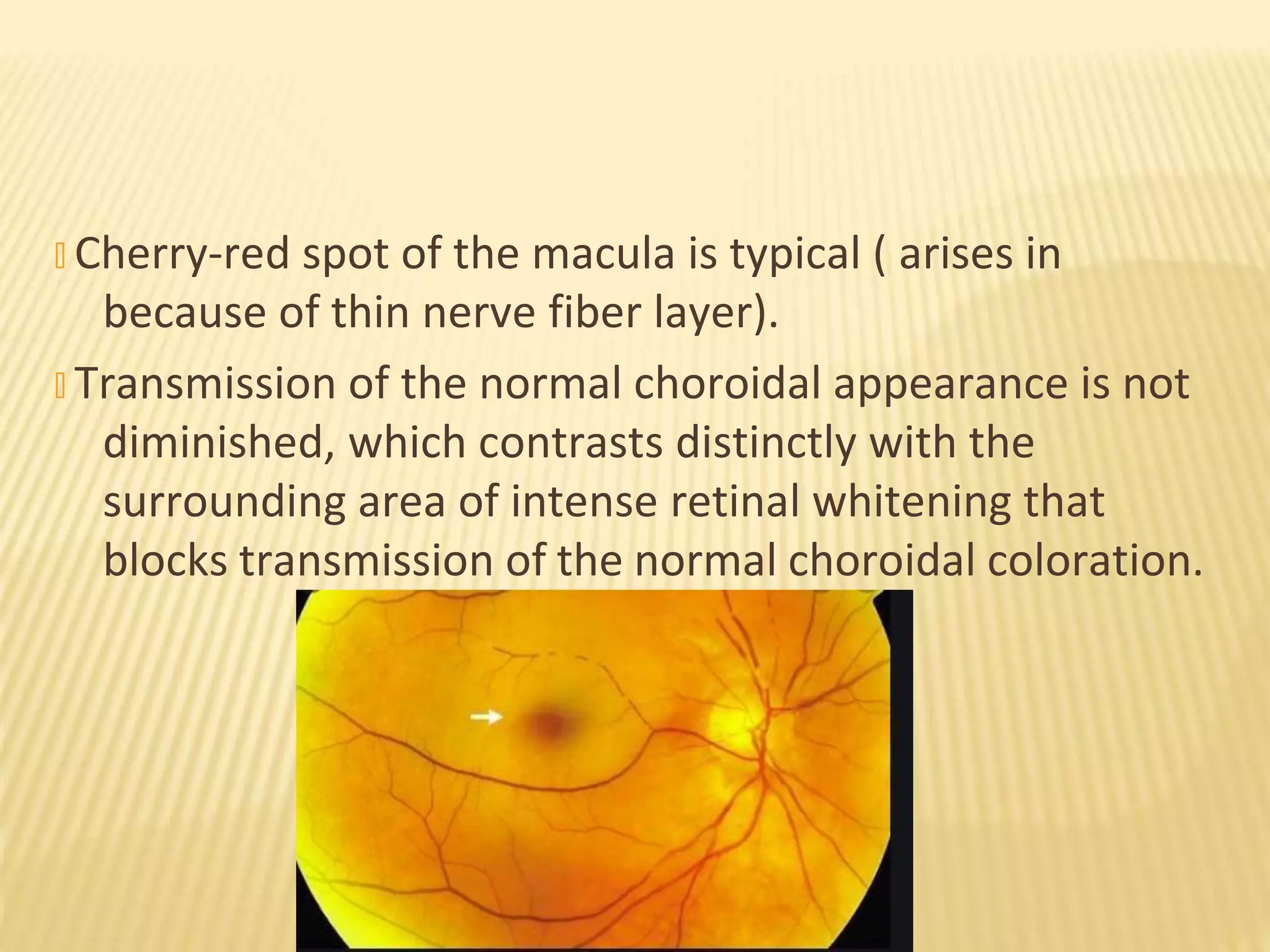

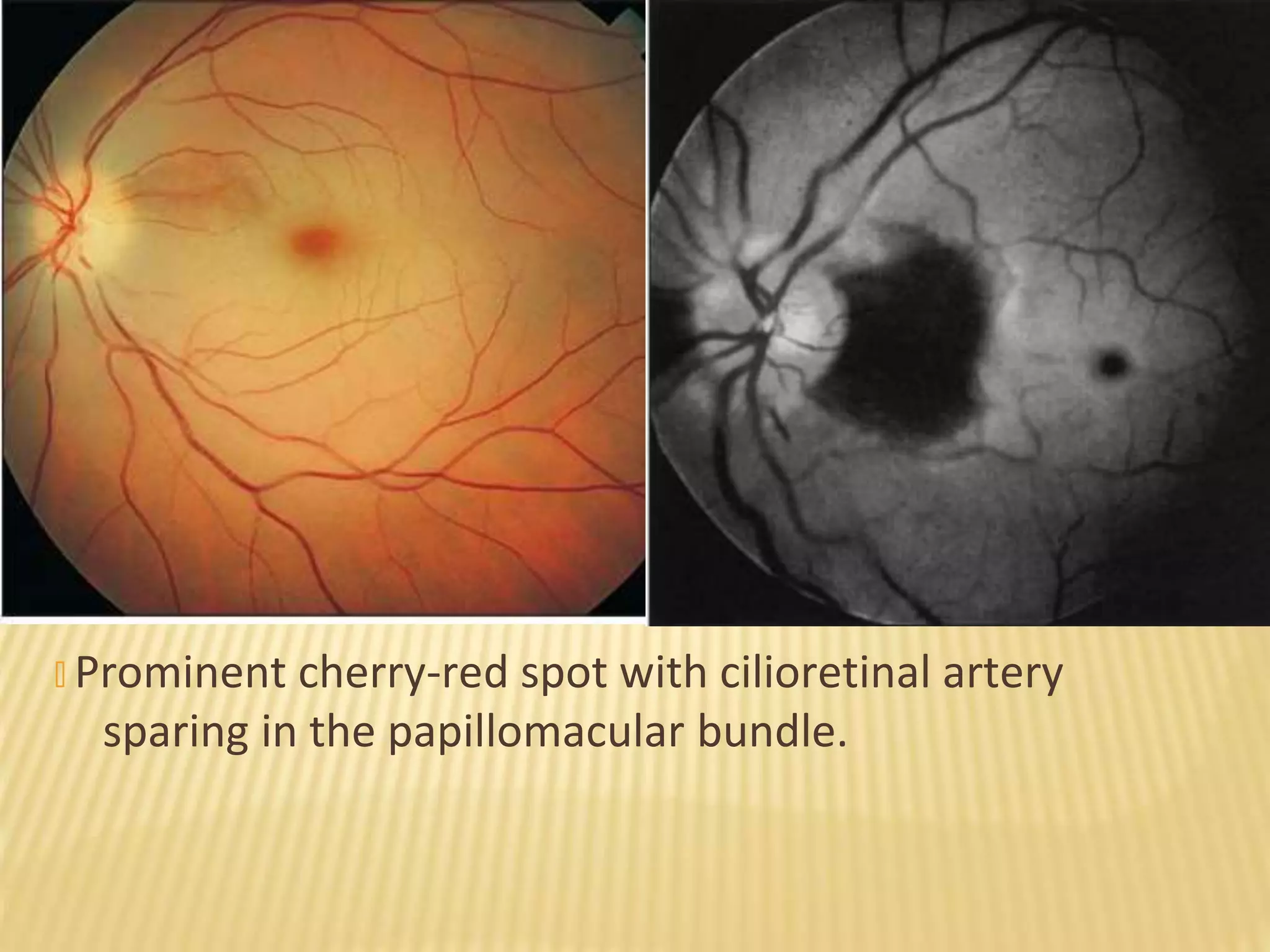

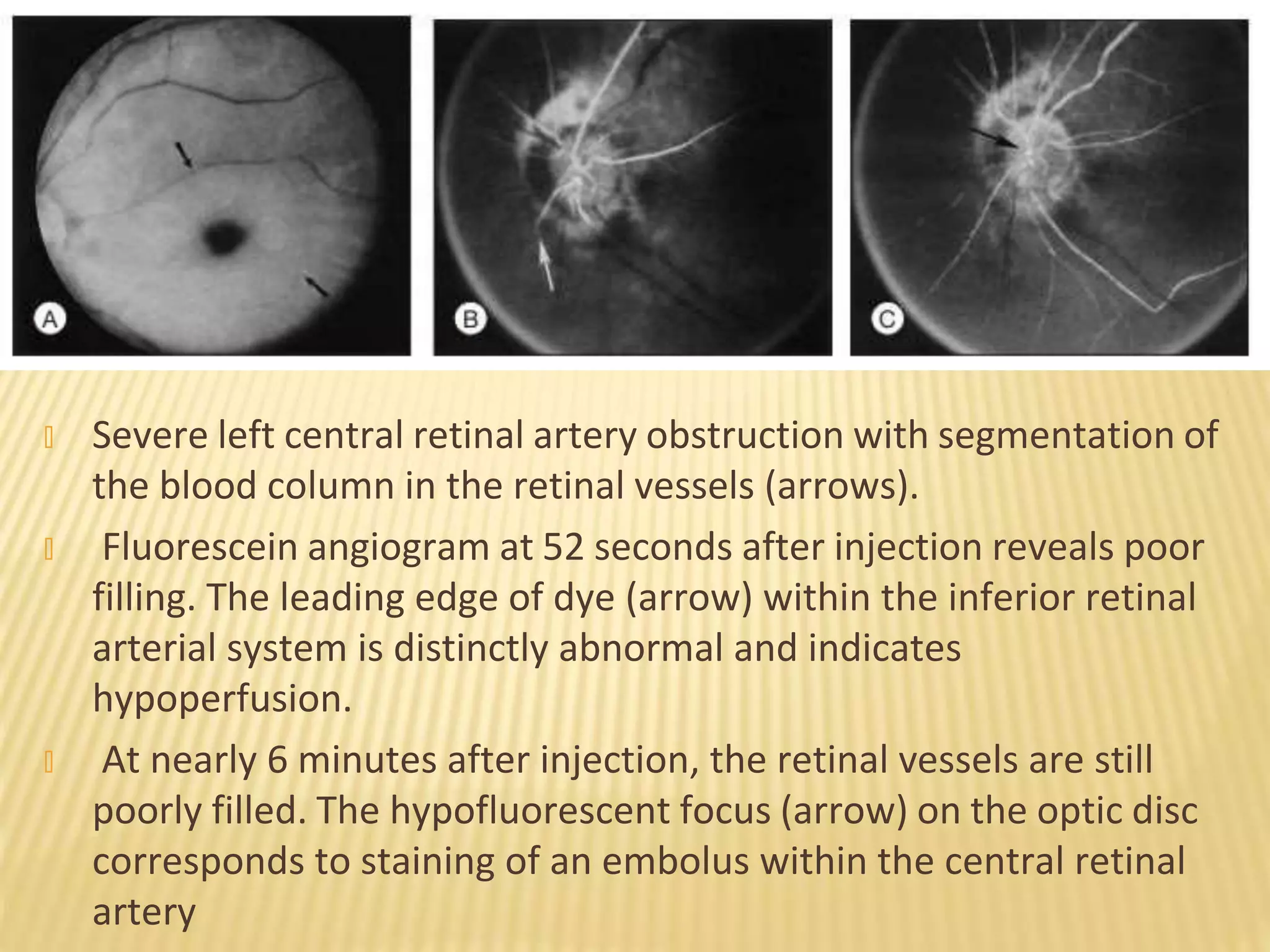

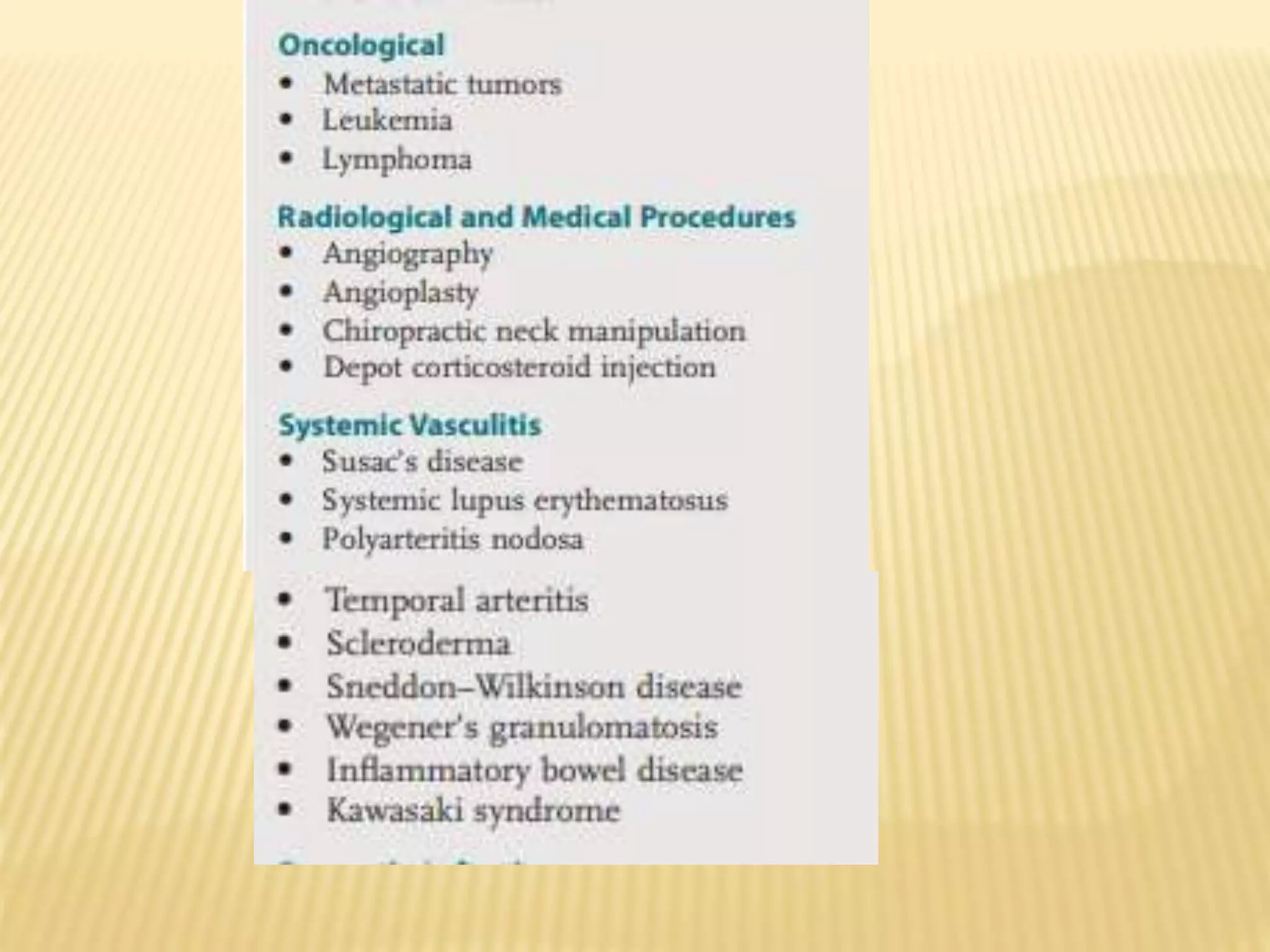

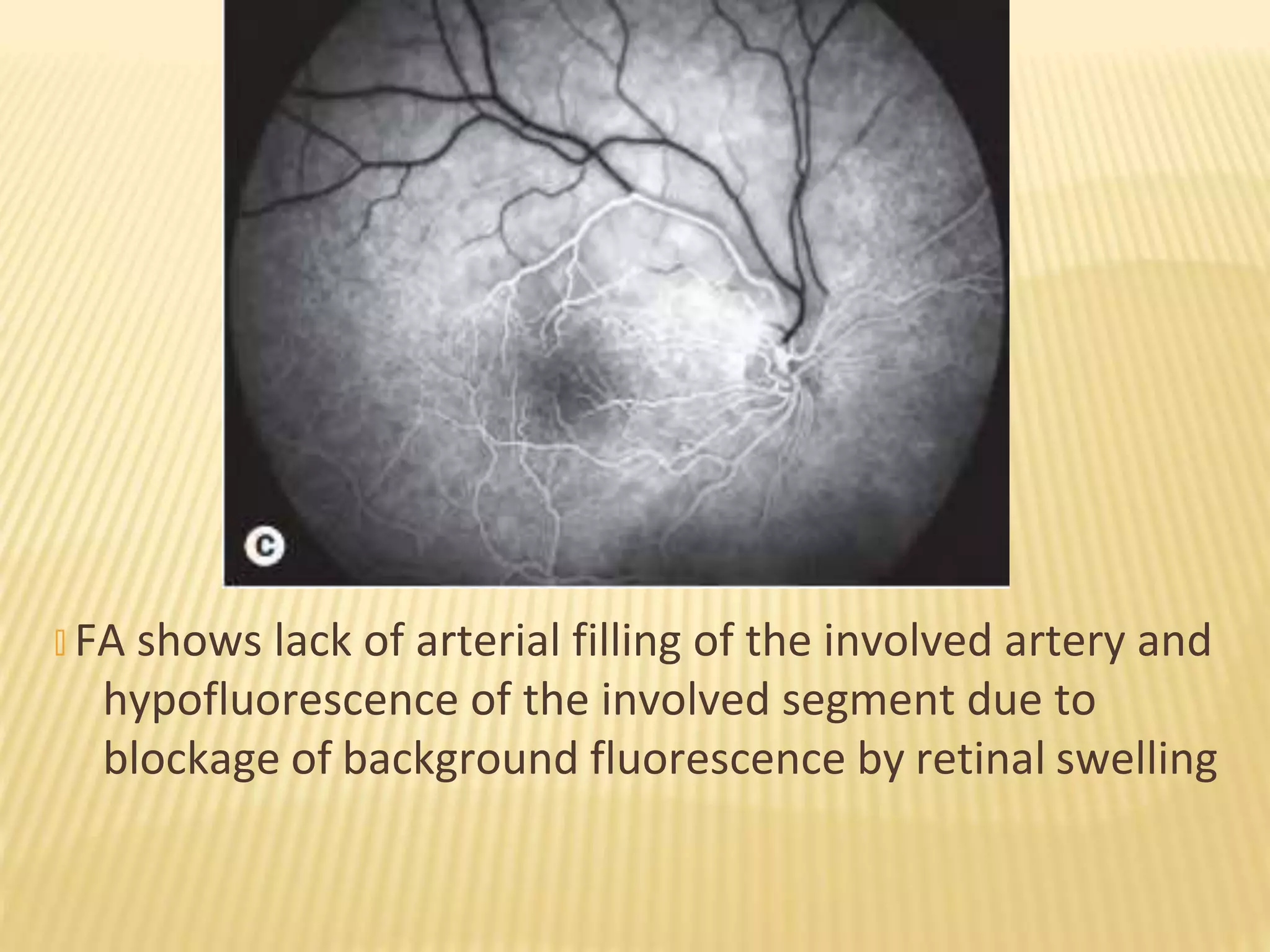

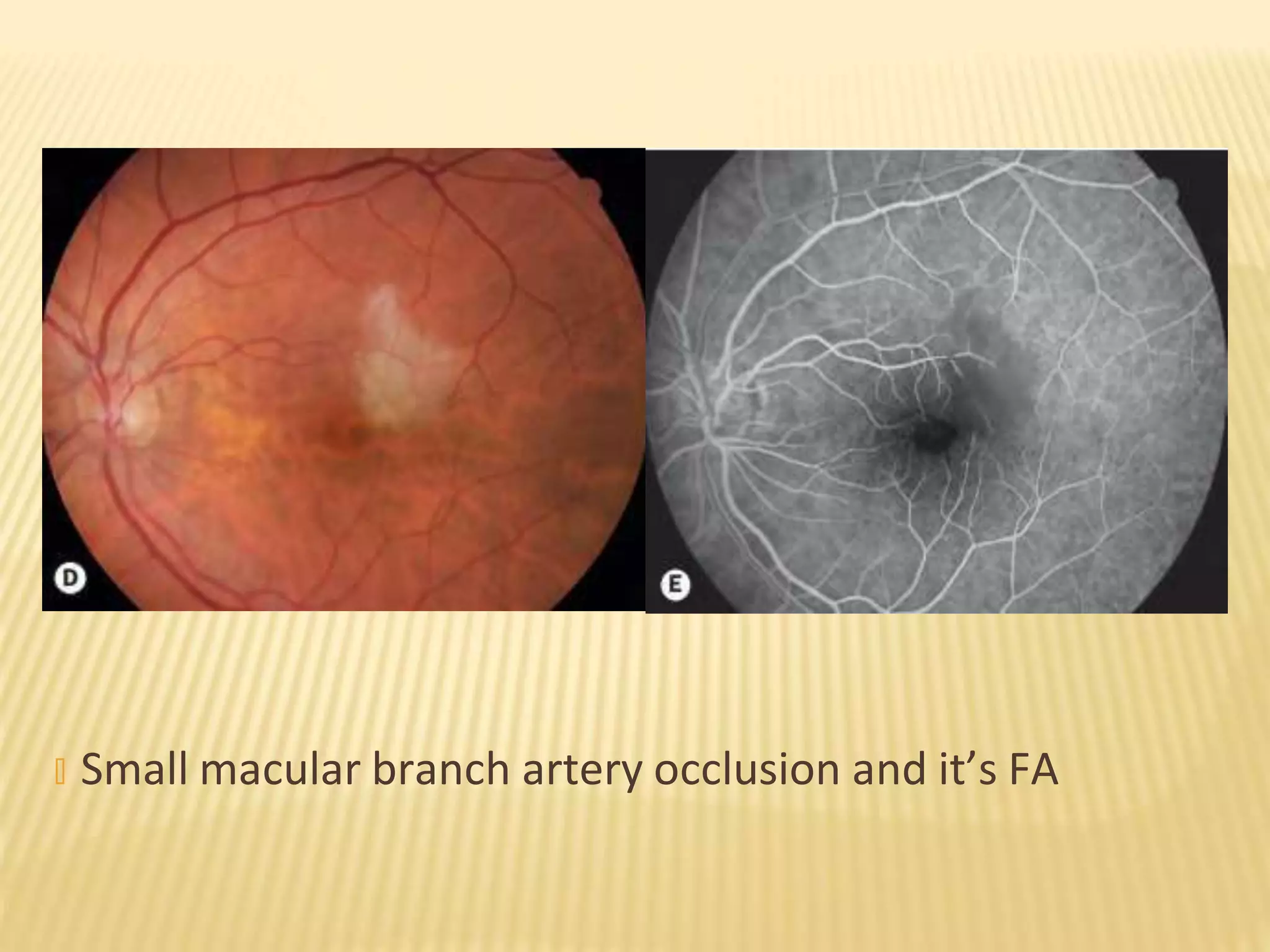

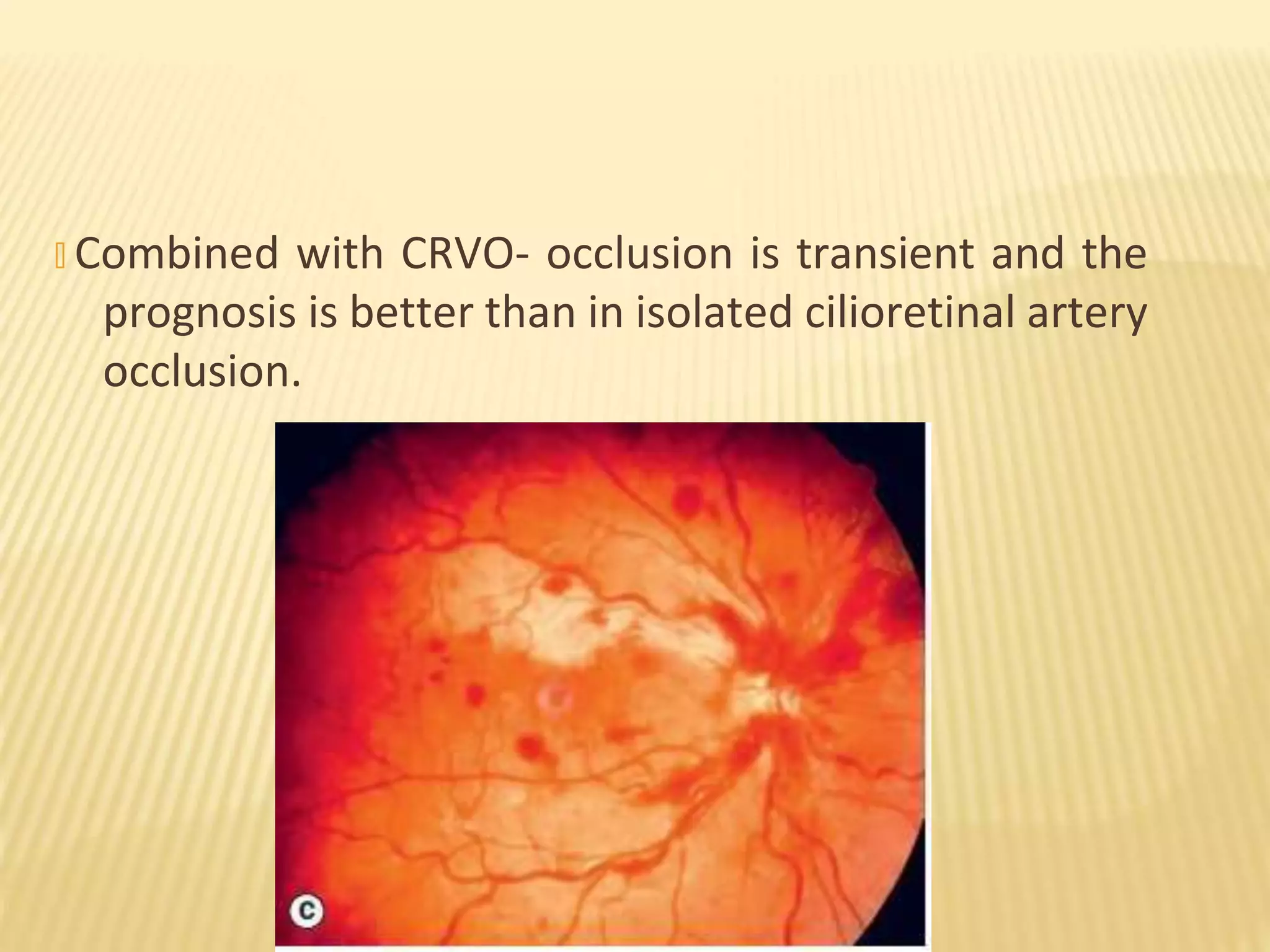

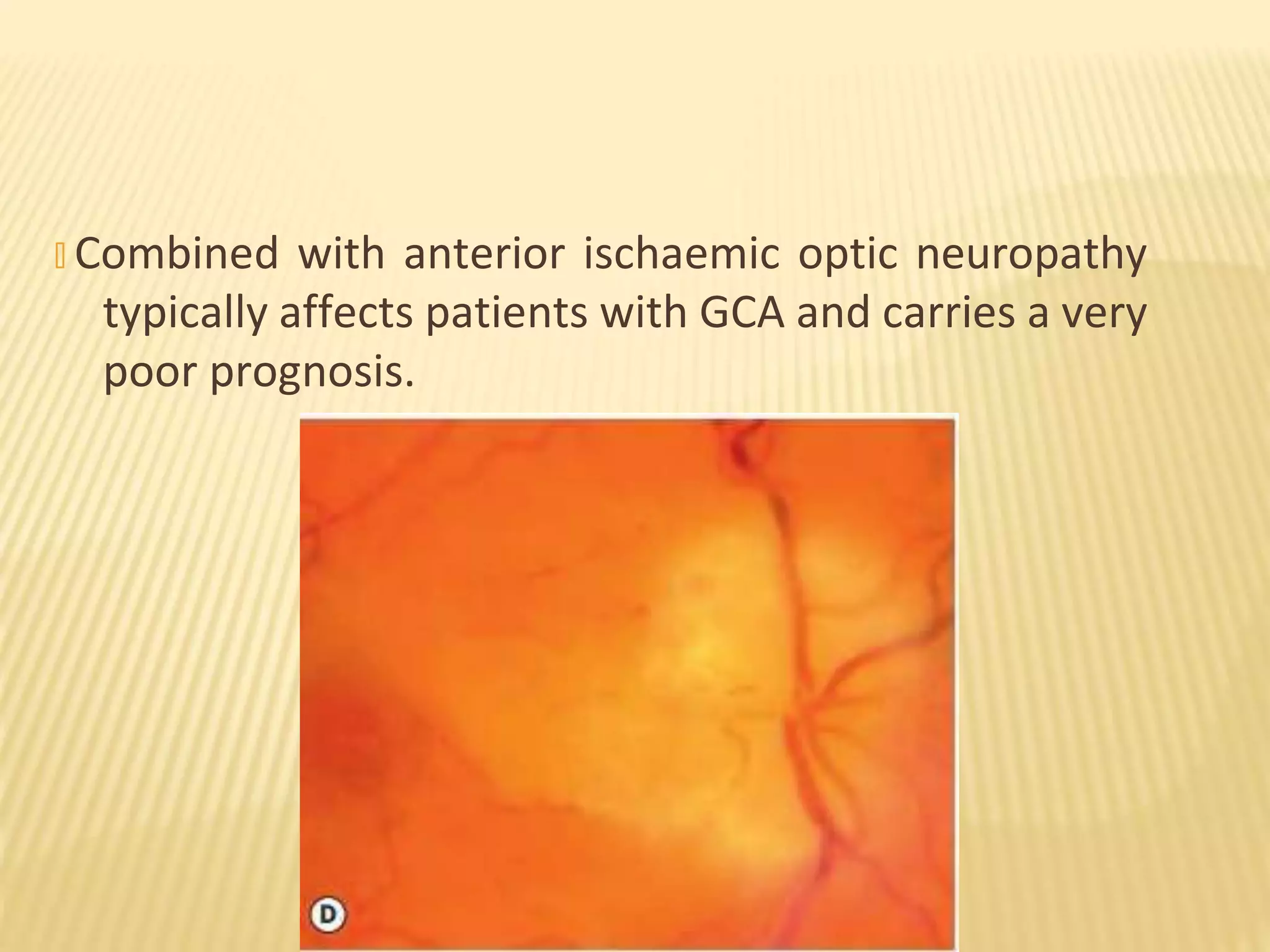

This document summarizes retinal artery occlusion. It describes central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) which occurs within the optic nerve and branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) which occurs distally. The blood supply and causes are discussed, including embolism originating from atherosclerotic plaques. Clinical features include sudden painless vision loss and characteristic fundus findings like retinal whitening. Prognosis is generally poor for CRAO but may improve spontaneously for BRAO. Systemic evaluation is important to identify underlying conditions.