The document discusses several previous studies conducted by Amity University experts related to agriculture and remote sensing. One study analyzed big data pattern mining using graphs to identify clusters and frequent subgraphs. Another used thermal imaging and hyperspectral remote sensing to monitor crop water deficit stress in rice genotypes and identify optimal wavelengths. A third compared modeling approaches to monitor water deficit stress in rice using hyperspectral data and measured relative water content. The studies demonstrated applications of machine learning, remote sensing, and hyperspectral data for agricultural monitoring and analysis.

![14 | P a g e

Name of Study

Name of study

Methods of LeafArea for Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.) Bertoni

Leaf area is a valuable index for evaluating growth and development of sweet herb

Stevia [Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.) Bertoni]. A simple methodology was developed

during 2006 to estimate the leaf area through Leaf Area Distribution Pattern

(LADP) and regression equations. Plant height, leaf height as well as the length and

breadth of all the measurable leaves were measured and their area was measured

through Area meter (AM 300) for a six month old crop of Stevia. A leaf area

coefficient of 0.548 was found to fit for the linear equation without intercept.

LADP was prepared with relative leaf height and relative leaf area. Based on the

adjusted second order polynomial equation of LADP, the relative leaf height of

plants representing the mean leaf area was ascertained and a regression equation

was obtained to calculate the total leaf area of the plant. The results were validated

with 3, 4 and 5 months old crops as well as with another accession. Different

combinations of prediction equations were obtained from length and breadth of all

leaves and a simplest equation i.e, linear equation was used to predict the leaf area.

A non-destructive methodology for estimating leaf area of Stevia based on linear

measurement was developed in this study.

SIMULATION AND VALIDATION OF CERES-MAIZE AND CERES-

BARLEY MODELS

Investigations were carried out for determination of genotypic co-efficients of

important varieties of maize and barley, simulation and validation of CERES-Maize

and CERES- Barley crop models for growth, yield and yield attributes, and working

out simulation-guided management practices for yield maximization of both the

crops. Field experiments comprising of four dates of sowing (June 1, June 10, June

20 and June 30) and four varieties (KH 9451, KH 5991, early composite and local)

of maize and four dates of sowing (October 10, November 1, November 20 and

December 10) and three varieties (Dolma, Sonu and HBL-113) of barley were

conducted during Kharif 2002 to Rabi 2004-05 in split plot design. Observations on

development stages, dry matter accumulation (leaves, stem and grains) at 15 days

interval, yield attributes, yield (grains, stover/straw and biological), nitrogen

content and uptake were recorded. Genotypic coefficients of important

recommended varieties of maize and barley were worked out. CERES-Maize model

successfully simulated phenological stages, yield attributes (except test weight),

yield and also N uptake, but failed to simulate accurately dry matter accumulation

in different plant parts at different growth periods. CERES-Barley model also

successfully simulated phenological stages, yield attributes and grain yield, but

failed to simulate straw yield, dry matter accumulation in different plant parts at

different growth periods and N content and uptake. Both the models were validated

with fair degree of accuracy. Simulation guided management practices were

worked out under potential production and resource limiting situations. In case of

maize, best time of sowing of both hybrids(KH 9451, KH 5991) was worked out to

be last week of April. While for early composite, first week of May proved

advantageous and for local second fortnight of April. The best schedule of N

application was 60 kg /ha at sowing time and 30 kg/ha at knee high stage for all

varieties except for local where it was 60 kg /ha at sowing and 30kg/ha at knee high

stage and 30 kg/ha at silking. In case of barley, best time of sowing for Dolma and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-14-320.jpg)

![the regular monitoring and assessment are a prerequisite to

understand the water quality. Many governments are now

seeing other approaches in response to increasing aware-

ness of degrading lake water resources and growing con-

cern over the significant fiscal burden of agricultural

subsidies.

Earth observation data sets, e.g., satellite images, are

quite useful, which could be used for synoptic representa-

tion of any area (Srivastava et al. 2010). Land use/land

cover change (LULCC) quantification is one of the major

application of earth observation data sets, and it is impor-

tant for assessing global environmental change processes

and helps in making new policies and optimizing the

maximum use of natural resources in sustainable manners

(Srivastava et al. 2012). The land use/land cover

(LULC) types, such as agricultural land and urban area, are

associated with human activities that often affect the water

quality and change the aquatic ecological environment;

hence, monitoring spatial–temporal changes is essential to

understand the driving factors which influence the water

quality of any area. Amin et al. (2014) and Mishra and

Garg (2011) has did research on lake of India by implying

the satellite data.

According to Singh et al. (2015), the concept of water

quality to categorize water according to its degree of purity

or pollution dated back to year 1848. Around the same

time, the importance of water quality to public health was

recognized in the UK (Snow 1856). Water Quality Index

(WQI) methodologies have been developed to provide

single number that expresses the overall water quality at a

certain location and time, based on several water quality

parameters (Parmar and Bhardwaj 2013; Vasanthavigar

et al. 2010; Avvannavar and Shrihari 2008; Singh et al.

2015) and can be used to provide the overall summaries of

water quality on a scientific basis. Parmer and Bhardwaj

(2013) have applied WQI and fractal dimension approach

to study the water of Harike lake on the confluence of Beas

and Sutlej rivers of Punjab (India). Many researchers have

discussed the importance and applicability of WQI for

water characterization (Couillard and Lefebvre 1985;

House and Newsome 1989; Bordalo et al. 2001; Smith

1989; Swamee Tyagi 2000; Sanchez et al. 2007).

In combination with remote sensing water quality, the

use of multivariate statistical techniques offers a detailed

understanding of water quality parameters and possible

factors that influence the water quality behavior (Srivastava

et al. 2012). Principal component analysis (PCA) and factor

analysis (FA) offer a valuable tool for consistent, reliable,

effective management of water resources (Srivastava et al.

2012; Singh et al. 2009, 2013d, 2015). Many authors in past

have used multivariate statistical techniques to characterize

and evaluate surface and groundwater quality and have

found it interesting for studying the variations caused by

geogenic and anthropogenic factors (Shrestha and Kazama

2007; Singh et al. 2005). For understanding the lake water

quality, multivariate statistical techniques integrated with

remote sensing, and WQI (Srivastava et al. 2012) could be

used for identification of the possible factor/sources that

influences urban lake water quality.

As the study area occupied by hard basaltic terrain and

groundwater resource are limited. Hence, largely the water

supply in urban areas setteled at hard rock terrain depends

on lake water too for drinking and small scale industrial

purposes. The water supply of bhopal urban area mainly

depends on the Bhopal lake for drinking, irrigation and

small scale industries.

The specific objective of this research was focused on to

quantify the historical changes in LULC using satellite data

sets and its probable impact on the lake water quality with

integration of statistical techniques to know the pollution

status of Bhopal lake and to categorize lake water by WQI

method. The findings of the study will be useful for the

restoration of Bhopal lake.

Materials and methods

Description of study area

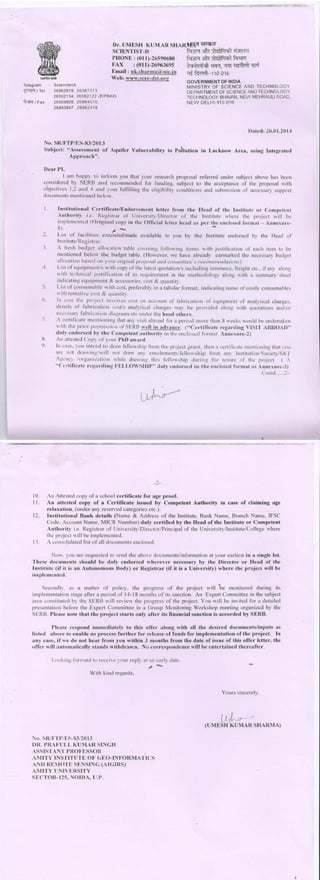

District Bhopal [latitudes 20°100

–23°200

N and longitudes

77°150

–77°250

E (Fig. 1)] is the capital city of the state of

Madhya Pradesh, India. Upper lake commonly known as

Bhoj wetland is the main lake of the city and provides

water to the dwellers. The lake surrounded by natural

landscape, settlements and agricultural fields. The average

annual rainfall is 1270 mm. The southern part of the city

receives more rainfall than northern part of the city. The

maximum rainfall takes place during the month of July.

The area is drained by small drains which are lastly

contributing water to the river Betwa in the downstream.

Bhopal has been growing at a fast rate due to urban

development and industrialization, in search of better

facilities and for educational purposes. The major part of

the city is covered by Vindhyan hills and by basaltic

Deccan trap. The Deccan trap covers almost one-third of

the area followed by Vindhyan sandstone (Singh and Singh

2012). In Deccan trap basalts, aquifer is encountered at

shallow depth and in Vindhyan sandstone depth ranges

more than 150 meter below ground level (mbgl). The water

supply to Bhopal city mainly comes from surface water

bodies and small amount by groundwater. Nowadays, a

number of boreholes/tube wells are drilled in the area

without consideration of hydrological status of the aquifer

formation to meet the water requirement, and this unaware

drilling has also led to the declining trend of water level

and also failure of well in successive years. Upper lake is a

446 Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2016) 13:445–456

123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-45-320.jpg)

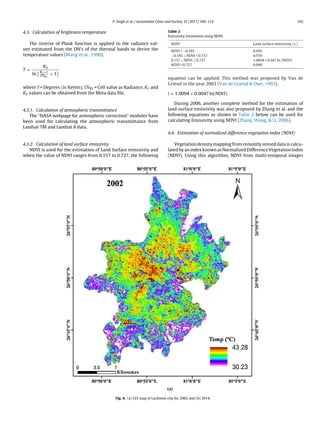

![for errors or other sources of variation, i the sample num-

ber, j the variable number and m the total number of

factors.

Results and discussion

Hydrochemistry of lake water

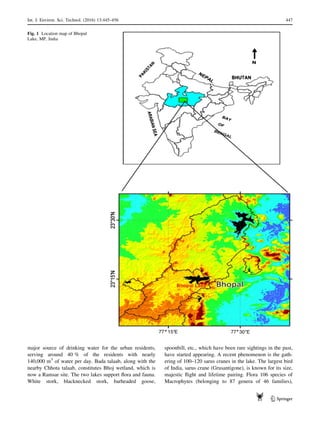

The descriptive statistics of 12 physicochemical parameters

at the 15 locations are summarized in Table 3. The average

value of total alkalinity 78.67, 60.07 and 57.20 was

observed during the pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-

monsoon seasons. Carbonate alkalinity average value was

13.19, 11.80 and 6.80, and bicarbonate alkalinity was

65.49, 49.43 and 50.96; total hardness average value was

85.25, 94.77 and 89.84, calcium hardness was 60.12, 67.10

and 68.58 and magnesium hardness was 25.14, 27.67 and

21.27 in the pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon

seasons, respectively. Calcium and magnesium are an

essential nutrient that is required by all living organisms.

Calcium and magnesium are entirely derived from rock

weathering. The sources of Ca mainly are carbonate rocks

containing calcite (CaCO3) and dolomite [(CaMg(CO3)2],

with a lesser proportion derived from Ca-silicate minerals.

Calcium is usually one of the most important contributors

to hardness. The average value of Ca was 25.25, 28.18 and

28.80, magnesium 6.11, 6.72 and 5.17 in the pre-monsoon,

monsoon and post-monsoon seasons, respectively.

Chloride is extremely mobile and very much soluble in

surface water. The main geogenic sources of chloride are

sea salt and dissolution of halite (NaCl) in bedded evap-

orites or dispersed in shales, and anthropogenic sources are

domestic and industrial sewage, mining, and road salt

runoff. The average value of chloride was 6.13, 21.03 and

19.35 in the all three seasons, respectively.

Phosphorus is a vital and often limiting nutrient. The

most common minerals are apatite, which is calcium

phosphate with variable amounts of hydroxyl-, chloro-, or

fluoro-apatite and various impurities. Some other phos-

phate minerals contain aluminum or iron. The anthro-

pogenic sources of phosphorus are domestic sewage, as the

element is essential in metabolism, industrial sewage and

household detergents. Phosphates and nitrates are the major

cause of eutrophication problem in lakes. The average

values of phosphate were 1.05, 0.76 and 0.62, total phos-

phorous was 1.62, 1.91, and 1.80, organic phosphorous was

1.13, 1.16 and 1.18 and nitrate was 0.73, 0.73 and 0.64 in

the pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon season,

respectively. Aqueous geochemistry behavior of nitrogen is

strongly influenced by the vital importance of the element

in plants and animal nutrition. The anthropogenic sources

of nitrate in surface water are runoff from the agriculture

field, and leachates from the landfill sites. The BOD was

3.83, 4.83 and 4.42, and COD was 29.60, 21.06 and 15.73

in the pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon season,

respectively. The development activity and expansion of

the city leading to discharge of waste water in the upper

Table 3 Physicochemical properties of lake water samples during the three seasons (all the parameters units are in mg/l)

Parameters Pre-monsoon Monsoon Post-monsoon

Max Min Avg Std Max Min Avg Std Max Min Avg Std

Total alkalinity 129.60 61.60 78.67 18.55 98.00 49.00 60.07 12.03 78.67 46.67 57.20 7.50

Carbonate alkalinity 17.60 7.00 13.19 2.95 16.67 7.00 11.80 2.78 11.33 4.00 6.80 2.30

Bicarbonate alkalinity 118.40 46.00 65.49 19.84 94.50 36.50 49.43 13.99 76.00 42.67 50.96 8.06

Total hardness 146.00 74.80 85.25 17.53 155.50 79.50 94.77 18.13 116.67 62.67 89.84 17.23

Ca hardness 105.00 51.66 60.12 13.26 122.85 55.65 67.10 16.66 104.30 55.30 68.58 12.99

Mg hardness 41.00 18.56 25.14 5.90 33.73 19.48 27.67 5.27 42.07 7.37 21.27 10.38

Calcium content 44.10 21.70 25.25 5.57 51.60 23.37 28.18 7.00 43.81 23.23 28.80 5.46

Magnesium content 9.96 4.51 6.11 1.43 8.20 4.73 6.72 1.28 10.22 1.79 5.17 2.52

Chloride 31.17 12.99 16.13 4.27 35.21 16.23 21.03 4.54 27.64 15.65 19.35 2.83

Phosphate 3.19 0.49 1.05 0.68 3.14 0.18 0.76 0.74 3.06 0.12 0.62 0.72

Total phosphorus 3.56 0.94 1.62 0.71 4.05 1.15 1.91 0.8 3.93 1.03 1.80 0.80

Organic phosphorus 2.31 0.43 1.13 0.47 2.33 0.45 1.16 0.47 2.66 0.55 1.18 0.51

Nitrate 1.88 0.11 0.73 0.46 1.86 0.09 0.73 0.45 1.77 0.07 0.64 0.46

BOD 4.88 3.08 3.83 0.56 11.60 3.40 4.83 1.94 10.00 2.00 4.42 2.60

COD 44.80 23.20 29.60 4.70 35.00 16.06 21 4.75 30.67 12.00 15.73 4.37

450 Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2016) 13:445–456

123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-49-320.jpg)

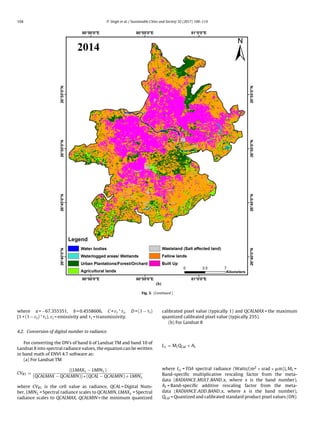

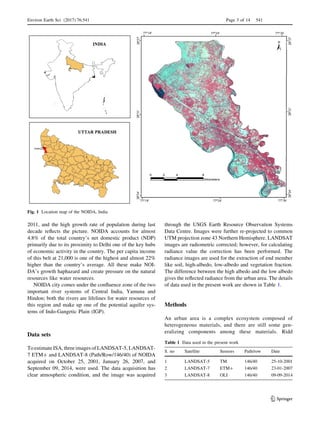

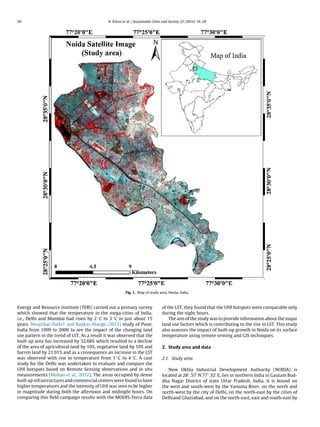

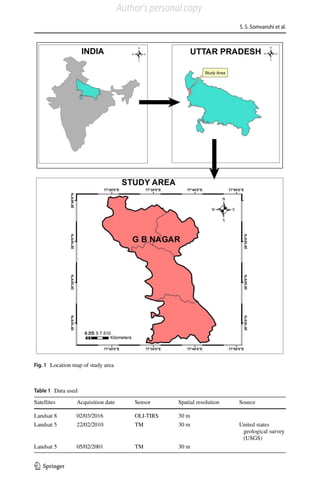

![P. Singh et al. / Sustainable Cities and Society 32 (2017) 100–114 103

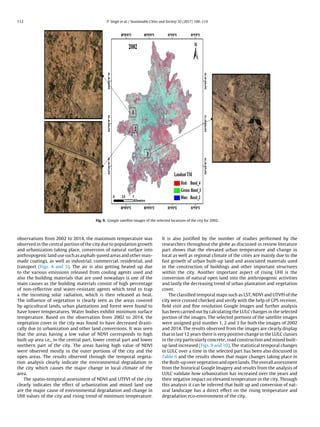

3.3. Image classification

Supervised classification scheme has been used for the pro-

cess of image classification in which training sets were selected

for image classification using Maximum Likelihood classifier

(MLC), a statistical decision in which the pixels are assigned

based on the class of maximum probability. Image classifica-

tion was used to define the Land use/Land cover types into

seven classes, namely, Built up, Water logged areas/Wetlands,

Wasteland (Salt affected land), Urban Plantations and Forest,

Agricultural lands, Fallow lands and Water bodies have been

categorized. As described by Lillesand, Kiefer, and Chipman

(2014), confusion matrix was also generated from the classified

image and signature file for the accuracy assessment. Overall

accuracy of LULC map was 88.38% and Kappa coefficient was

0.832.

4. Methodology

4.1. Mono-window algorithm for the retrieval of LST

In this study, land surface temperature (LST) of Lucknow city

was estimated from the thermal infrared bands of Landsat satel-

lite data’s using the mono-window algorithm proposed by Liu and

Weng (2011), Liu and Zhang (2011) and Qin, Zhang, Amon, and

Pedro (2001). This algorithm is carried out using three main param-

eters, namely, transmittance, emissivity and mean atmospheric

temperature. TIR band 6 of Landsat TM and TIR band 10 of Landsat

8 records the radiation with spectral range ranging from 10.40 to

12.50 for Landsat TM data’s and 10.60 to 11.19 for Landsat 8 data’s.

Formula:

Tc = {a(1 − C − D) + [b(1 − C − D) + C + D]Ti − D ∗ Ta}/C

Fig. 3. (a) Land use/land cover map of Lucknow city for 2002 and (b) 2014.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-59-320.jpg)

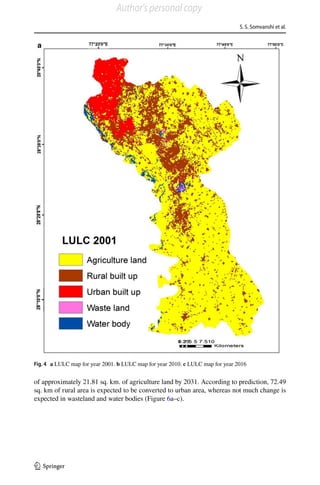

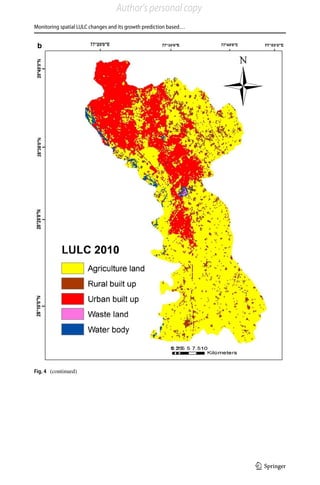

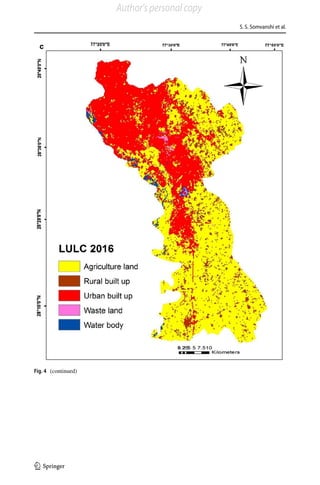

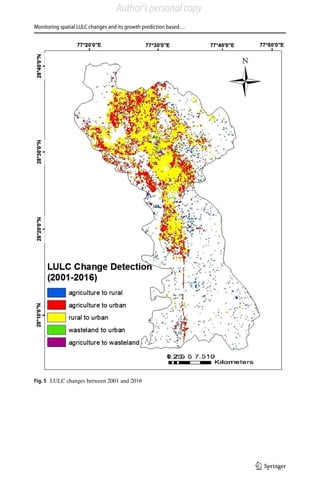

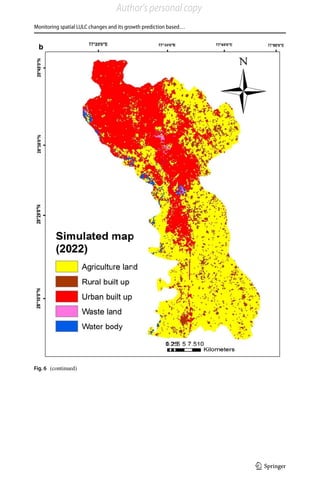

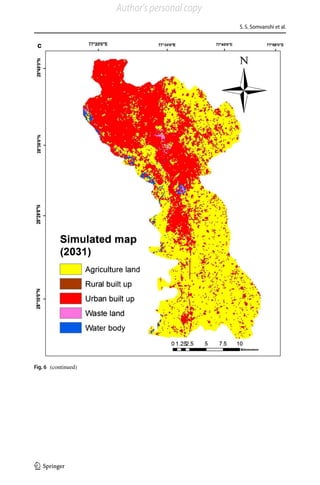

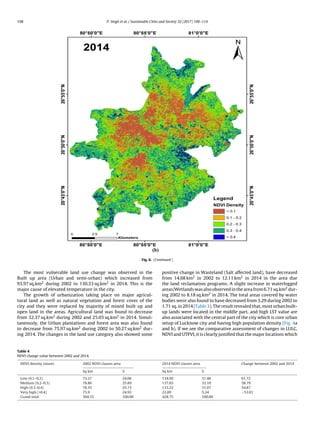

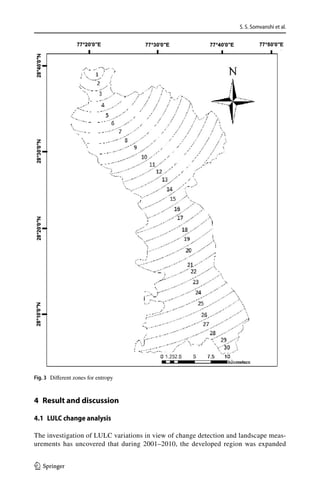

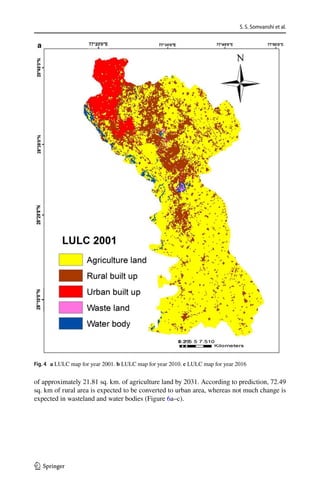

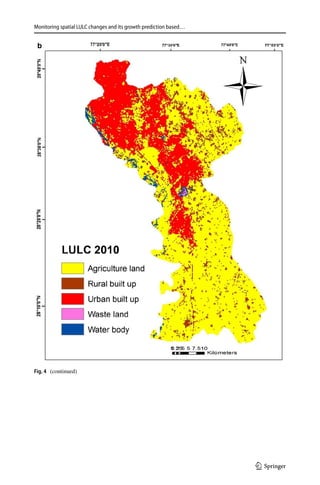

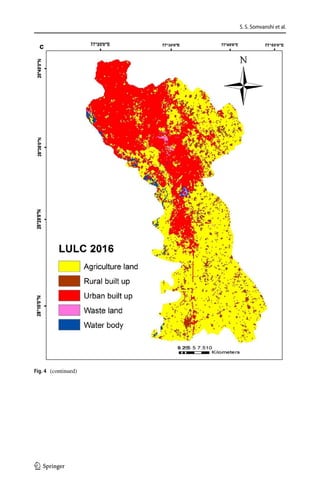

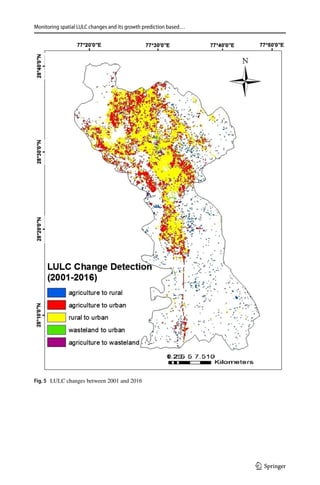

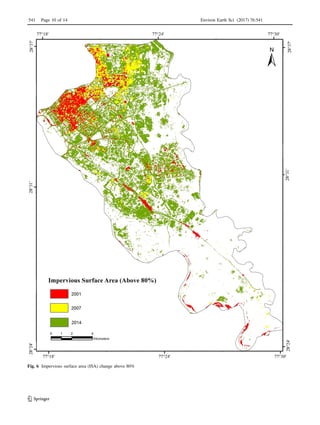

![Monitoring spatial LULC changes and its growth prediction based…

1 3

by 271.43 sq. km. The LULC cover change in the area clearly indicates that in last 2

decades the growth of urbanization increases drastically and the major changes were

observed in conversion of agricultural land into urban and rural area in urban built up.

The urban built-up area in 2001 was 114.88 sq. km, and agriculture area was 1015.53

sq. km; however, in 2010, the urban built-up increased to 386.31 sq. km and agricul-

ture land decreased to 931.53 sq. km (Fig. 4a–c). It is also observed that large-scale

change in rural area into dense built-up land due to the growth in construction projects.

Another important LULC change was observed between second phase of development

from 2010 to 2016 in urban built land and its increase up to 120.32 sq. km in last

6 years (Table 2). It is observed that more than 34.13 sq. km of agricultural land has

been converted to the urban built-up area in the last 16 years and most of the urbaniza-

tion has taken place on agricultural and open lands (Fig. 5). The unexpected expan-

sion of urban developed regions not just brought about the discontinuity of crop land,

but also decreased the productivity of crop and groundwater resource due to reduction

in surface recharge area. Ultimately, it caused a serious problem for food and water

security.

4.2 Urban sprawl analysis

The Shannon’s entropy (Hn) was measured for the assessment of urban environment to

examine the degree of dispersion or compactness of the spatial growth of the city. The

highest range of Shannon’s entropy [Loge (30)] is 1.48, and entropy results obtained from

three study periods were 1.47, 1.46 and 1.46, respectively (Table 4). The values observed

for all the 3 years were towards 1.48 (log 30). The entropy results revealed that there was

urban expansion in the area exponentially since 2001 in south-east direction. The rate of

overall expansion of the area has very negative impact on ecological, environmental, eco-

nomic and social aspect (Mumford and Copeland 1961; Munda 2006; Bhatta et al. 2009).

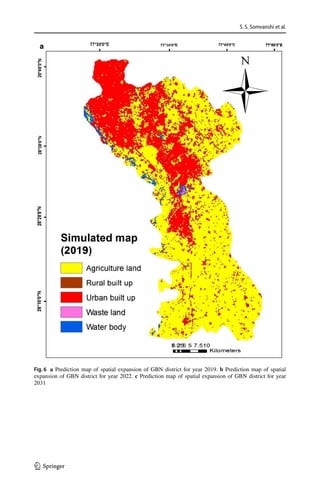

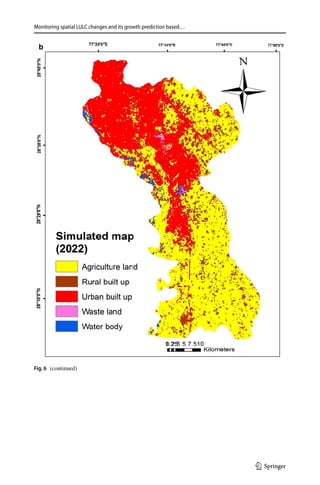

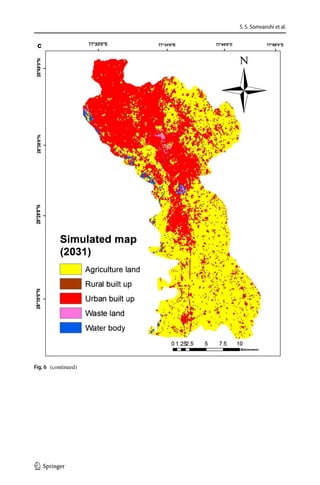

4.3 LULC prediction modelling

LULC maps of 2001 and 2010 were identified as input data to predict 2019 land use, 2010

and 2016 maps were used as input to predict 2022, and LULC maps of 2001 and 2016

were used as input data to predict 2031. According to the analysis during the study, the

land-use change will reach to extreme in 2019, 2022 and 2031 and urban area will increase

and occupy 40.29%, 40.65% and 41.69% of the district’s area, respectively (Table 5). How-

ever, cultivated land will decrease, respectively, year after year, resulting in potential loss

Table 5 Estimation of urban sprawl and LULC changes for 2019, 2022 and 2031

Classes 2019 2022 2031

Area (sq. km.) Area (%) Area (sq. km.) Area (%) Area (sq. km.) Area (%)

Agriculture land 818.94 56.6 814.24 56.46 801.61 55.59

Rural built up 18.31 1.26 18.12 1.25 15.70 1.08

Urban built up 581.12 40.29 586.18 40.65 601.23 41.69

Wasteland 1.39 0.09 1.37 0.09 1.25 0.08

Water body 22.24 1.54 22.09 1.53 22.21 1.54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-79-320.jpg)

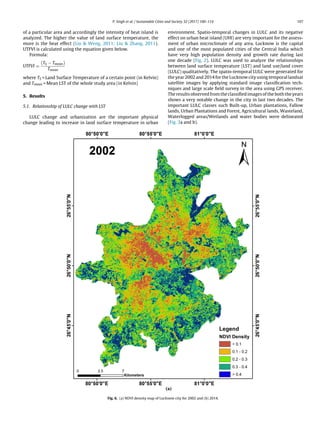

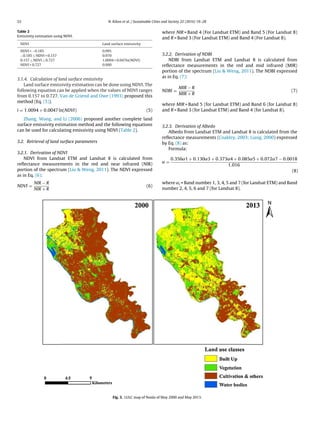

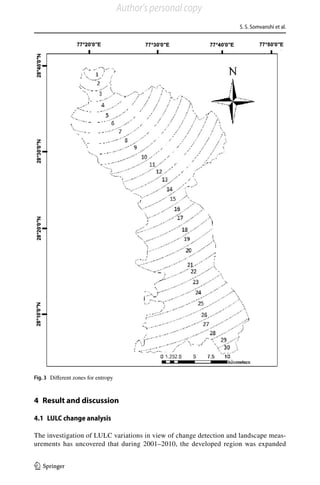

![N. Kikon et al. / Sustainable Cities and Society 22 (2016) 19–28 21

Table 1

Data used and their source.

Data used Data acquisition date Data source

LANDSAT ETM 1st May 2000 http://earthexplorer.

usgs.gov/LANDSAT 8 29th May 2013

the Hindon River. Noida is spread over an area of 203 km2, and has a

population of around 0.64 million. Noida has hot and humid climate

for most of the year. The weather remains hot during summers, i.e.,

from March to June, and temperature ranges from maximum of

48 ◦C to minimum of 28 ◦C. Monsoon season prevails during mid-

June to mid-September with an average rainfall of 93.2 cm (36.7 in.),

but sometimes frequent heavy rain causes flood. Temperatures fall

down to as low as 3 to 4 ◦C at the peak of winters. Noida also has

fog and smog in winters (http://noida.trade/cityClimatesection).

Due to a rapid industrialization and urbanization and infrastructure

development in Delhi and Noida, develops ecological imbalance

due to exploitation and overuse of environmental resources which

have adverse effect as UHI (Fig. 1).

2.2. Data used

2.2.1. Satellite data and other auxiliary data

The details of satellite images are given in Table 1 and other

auxiliary data as Survey of India Toposheets and MOSDAC data has

been used in the study.

2.2.2. Preprocessing

Satellite data pre-processing was carried out using ENVI 4.7

software. Each Landsat ETM and Landsat 8 data consisted of inde-

pendent distinct band images which was first layer stacked and

combined into a multi-band image. These images have a spatial res-

olution of 30 m per pixel. In this study the band 6 (thermal infrared

band) of ETM and band 10 (thermal infrared band) of Landsat 8 was

used to retrieve the LST by converting the Digital number (DNs)

into radiances. The bands within solar reflectance spectral range

were used for extracting the vegetation and built up indexes. After

pre-processing, the images of the study area were used for the anal-

ysis of UHI study. Further, processing has been carried out on Arc

GIS 10.2.1 software. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS

software.

3. Methodology used

3.1. Mono-window algorithm for the retrieval of LST

Mono-window algorithm proposed by Qin, Karnieli, and

Berliner (2001), for the retrieval of LST from Landsat TM 6 data have

been used in the study (Liu Zhang, 2011). This algorithm necessi-

tates three main parameters – emissivity, transmittance and mean

atmospheric temperature. Band 6 of Landsat ETM and band 10 of

Landsat 8 records the radiation with spectral range from 10.40 to

12.50 m for Landsat ETM and 10.60 to 11.19 m for Landsat 8. The

following expression is given below as Eq. (1):

Ts = {a(1 − C − D) + [b(1 − C − D) + C + D]Ti − D ∗ Ta}/C (1)

where a = −67.355351, b = 0.4558606, C = εi * i, D = (1 − i)

[1 + (1 − εi) * i), εi = emissivity and i = transmissivity.

3.1.1. Conversion of digital numbers to radiance

In order to convert the DN data of band 6 of Landsat ETM and

band 10 of Landsat 8 into spectral radiance Eqs. (2) and (3) can be

written in band math of ENVI 4.7 as:

Fig. 2. NASA webpage for atmospheric correction.

Source: atmcorr.gsfc.nasa.gov/

(a) For Landsat ETM

CVR1 =

(LMAX − LMIN )

(QCALMAX − QCALMIN) ∗ (QCAL − QCALMIN) + LMIN

(2)

where CVR1 is the cell value as radiance, QCAL = Digital Number,

LMIN = spectral radiance scales to QCALMIN, LMAX = spectral

radiance scales to QCALMAX, QCALMIN = the minimum quan-

tized calibrated pixel value (typically 1) and QCALMAX = the

maximum quantized calibrated pixel value (typically 255).

(b) For Landsat 8

L = MLQCal + AL (3)

where L = TOA spectral radiance (Watts/(m2 × srad × m)),

ML = band-specific multiplicative rescaling factor from the

metadata (RADIANCE MULT BAND x, where x is the band num-

ber), AL = Band-specific additive rescaling factor from the

metadata (RADIANCE ADD BAND x, where x is the band num-

ber), QCal = quantized and calibrated standard product pixel

values (DN). These useful values can all be obtained from the

meta-data file of the satellite image data.

3.1.2. Calculation of brightness temperature

Once the radiance values have been calculated using the DNs of

the thermal bands, the inverse of the Plank function is applied to

derive the temperature values (Wang et al., 1990) expressed as Eq.

(4).

T =

K2

ln

K1×ε

CVR1

+ 1

(4)

where T = degrees (in K), CVR1 = cell value as radiance. K1 and K2

values can be obtained from the meta-data file.

3.1.3. Calculation of atmospheric transmittance

The atmospheric transmittance for Landsat ETM and Landsat

8 data was calculated using the “NASA webpage for atmospheric

correction” module (Fig. 2).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-106-320.jpg)

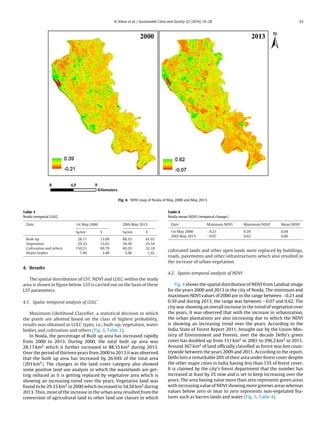

![Monitoring spatial LULC changes and its growth prediction based…

1 3

by 271.43 sq. km. The LULC cover change in the area clearly indicates that in last 2

decades the growth of urbanization increases drastically and the major changes were

observed in conversion of agricultural land into urban and rural area in urban built up.

The urban built-up area in 2001 was 114.88 sq. km, and agriculture area was 1015.53

sq. km; however, in 2010, the urban built-up increased to 386.31 sq. km and agricul-

ture land decreased to 931.53 sq. km (Fig. 4a–c). It is also observed that large-scale

change in rural area into dense built-up land due to the growth in construction projects.

Another important LULC change was observed between second phase of development

from 2010 to 2016 in urban built land and its increase up to 120.32 sq. km in last

6 years (Table 2). It is observed that more than 34.13 sq. km of agricultural land has

been converted to the urban built-up area in the last 16 years and most of the urbaniza-

tion has taken place on agricultural and open lands (Fig. 5). The unexpected expan-

sion of urban developed regions not just brought about the discontinuity of crop land,

but also decreased the productivity of crop and groundwater resource due to reduction

in surface recharge area. Ultimately, it caused a serious problem for food and water

security.

4.2 Urban sprawl analysis

The Shannon’s entropy (Hn) was measured for the assessment of urban environment to

examine the degree of dispersion or compactness of the spatial growth of the city. The

highest range of Shannon’s entropy [Loge (30)] is 1.48, and entropy results obtained from

three study periods were 1.47, 1.46 and 1.46, respectively (Table 4). The values observed

for all the 3 years were towards 1.48 (log 30). The entropy results revealed that there was

urban expansion in the area exponentially since 2001 in south-east direction. The rate of

overall expansion of the area has very negative impact on ecological, environmental, eco-

nomic and social aspect (Mumford and Copeland 1961; Munda 2006; Bhatta et al. 2009).

4.3 LULC prediction modelling

LULC maps of 2001 and 2010 were identified as input data to predict 2019 land use, 2010

and 2016 maps were used as input to predict 2022, and LULC maps of 2001 and 2016

were used as input data to predict 2031. According to the analysis during the study, the

land-use change will reach to extreme in 2019, 2022 and 2031 and urban area will increase

and occupy 40.29%, 40.65% and 41.69% of the district’s area, respectively (Table 5). How-

ever, cultivated land will decrease, respectively, year after year, resulting in potential loss

Table 5 Estimation of urban sprawl and LULC changes for 2019, 2022 and 2031

Classes 2019 2022 2031

Area (sq. km.) Area (%) Area (sq. km.) Area (%) Area (sq. km.) Area (%)

Agriculture land 818.94 56.6 814.24 56.46 801.61 55.59

Rural built up 18.31 1.26 18.12 1.25 15.70 1.08

Urban built up 581.12 40.29 586.18 40.65 601.23 41.69

Wasteland 1.39 0.09 1.37 0.09 1.25 0.08

Water body 22.24 1.54 22.09 1.53 22.21 1.54

Author's personal copy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/researchproposalamityuniversity-191017061352/85/Research-proposal-amity-university-124-320.jpg)