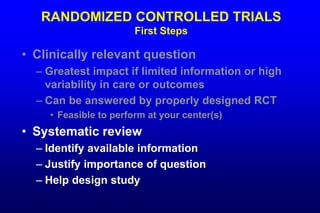

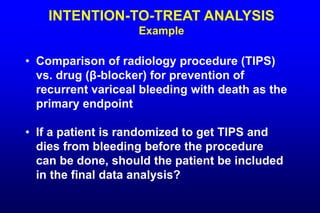

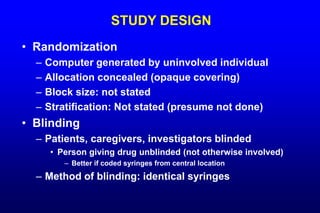

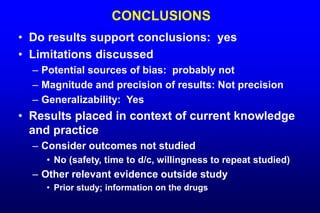

The document discusses the importance of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in clinical research, emphasizing that only sufficiently large RCTs can adequately control for confounding variables to minimize bias. It also explores the challenges and ethical considerations involved in conducting RCTs, such as practical impossibilities in certain scenarios, and outlines key elements necessary for designing effective trials, including randomization, blinding, and sample size determination. Additionally, the text highlights the importance of intention-to-treat analysis and correctly addressing potential biases to ensure the validity of study findings.