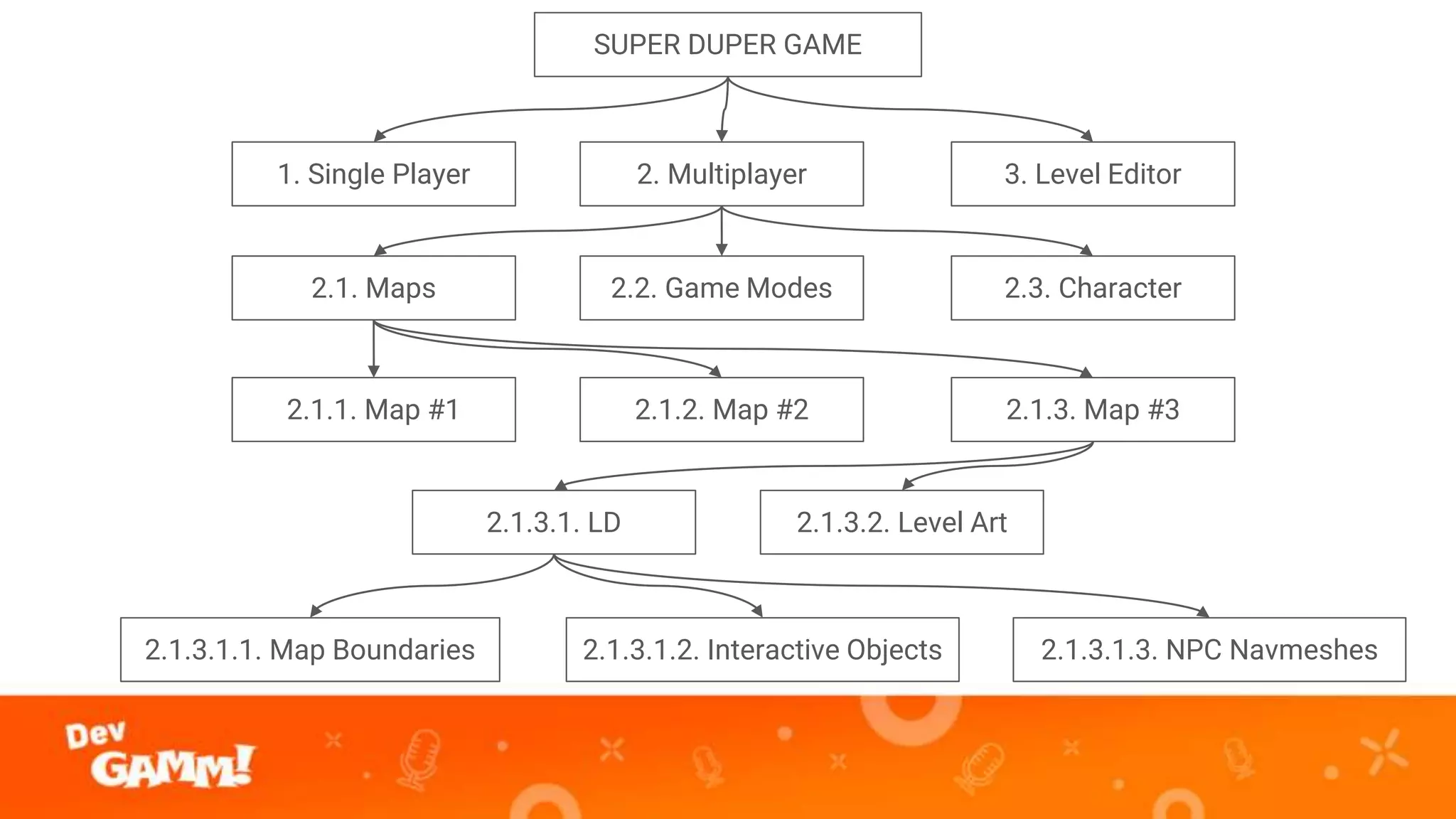

The document is a presentation by Tiberiu Cristea, a QA lead at Tinybuild LLC, aimed at indie game developers seeking success through quality assurance (QA) processes. It covers the importance of early and integrated QA, various types of testing, and the use of tools for effective QA management. Key takeaways include the necessity of proper QA for game success, which involves planning and tailored approaches depending on the game's features and target platform.