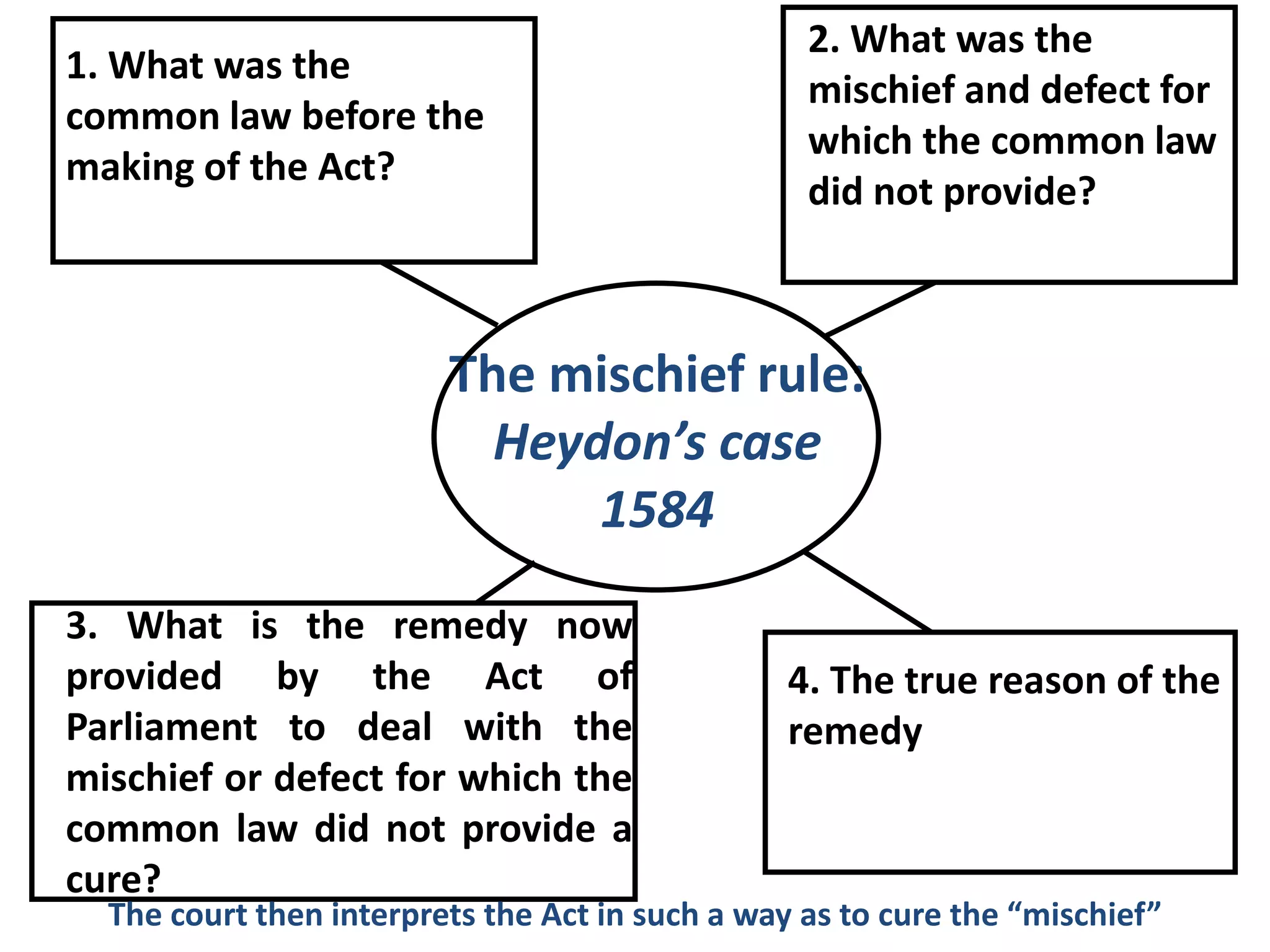

The document discusses the purposive approach to statutory interpretation. It provides context on the mischief rule from Heydon's case and explains that the purposive approach:

1) Goes beyond the literal meaning of words to consider the overall purpose and context of the legislation;

2) Allows judges to add or remove words from an Act to support what they view as the purpose for which the Act was created; and

3) Considers factors like the subject matter, scope, and background of the Act in addition to the ordinary meaning of words.

![R v Secretary of State for Health ex

parte Quintavalle [2003] 2 WLR 692](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/purposiveapproach-180908083205/75/Purposive-approach-9-2048.jpg)