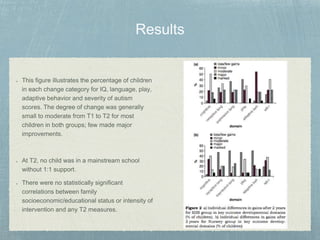

This study compared outcomes for 44 young children with autism who received either home-based early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) or autism-specific nursery provision over 2 years. Measures of IQ, language, play, adaptive behavior, and autism severity showed small to moderate improvements for most children in both groups, with no statistically significant differences between groups. The results did not support claims that EIBI leads to nearly half of children achieving normal functioning, and instead highlighted the heterogeneous nature and individual variability in outcomes for children with autism.