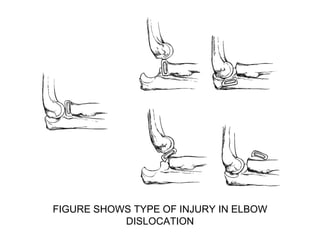

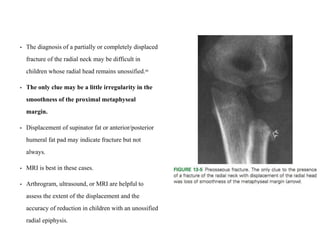

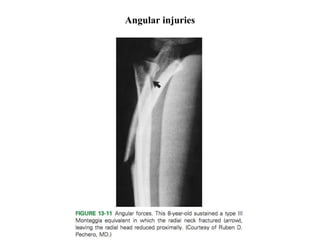

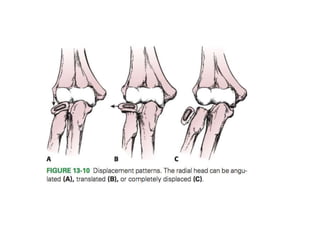

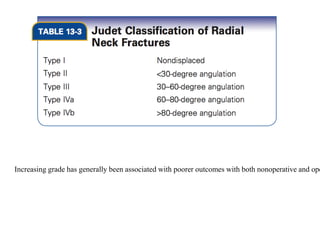

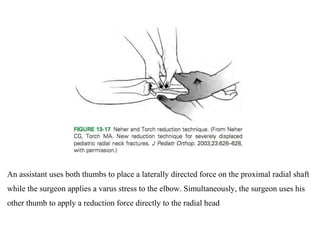

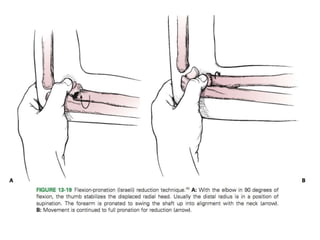

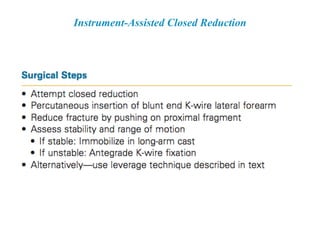

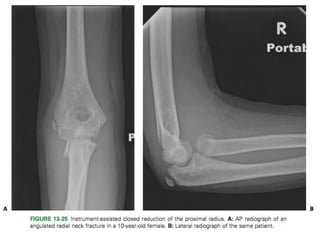

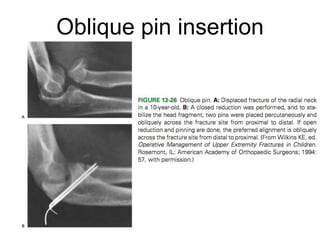

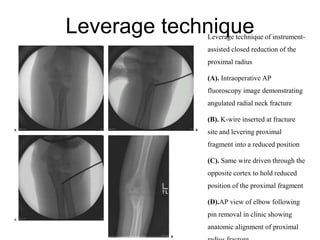

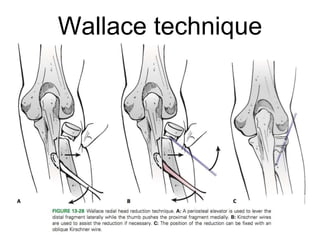

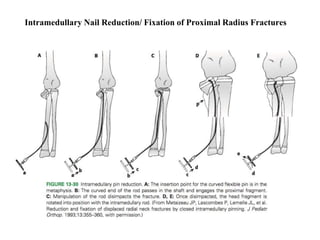

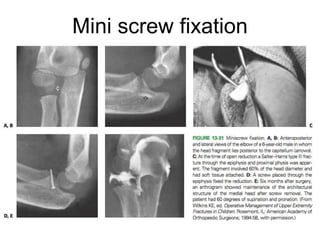

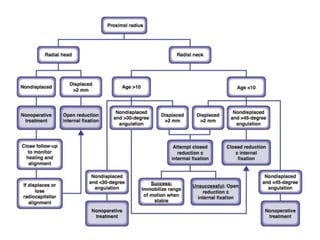

Fractures of the proximal radius in children most commonly result from a fall on an outstretched arm. These fractures involve the radial head, neck or metaphysis. Non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures can usually be treated non-operatively with immobilization and range of motion exercises once pain subsides. Operative treatment is considered for fractures with over 2mm displacement, angulation over 45 degrees in children under 10 or 30 degrees in older children, or those with instability or limited motion after closed treatment. Surgical options include closed or open reduction with pins, screws or plates to restore alignment and stability. Outcomes depend on the degree of initial displacement and need for manipulation, with minimally angulated fractures having the