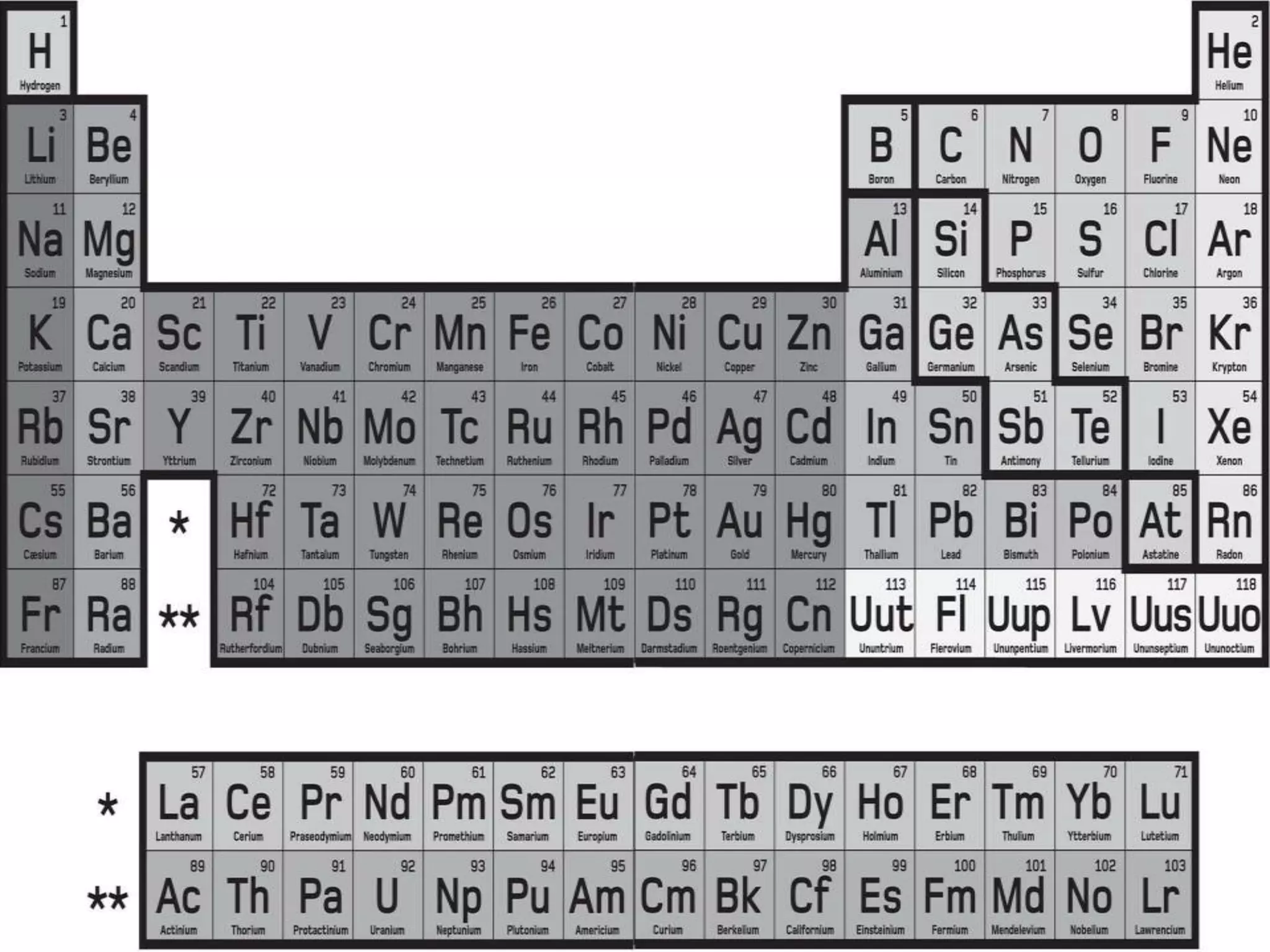

The document provides an overview of the properties of the periodic table, including:

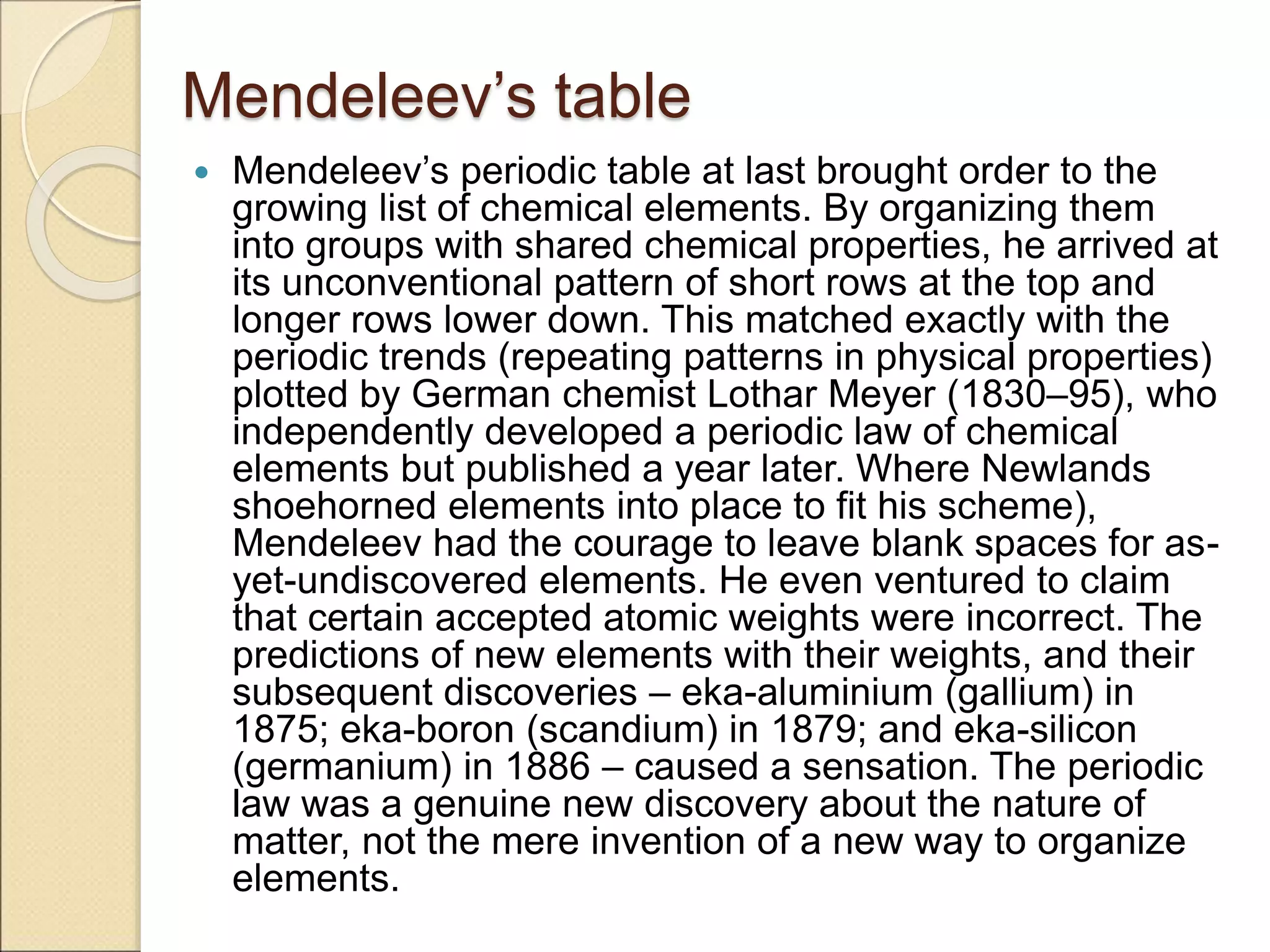

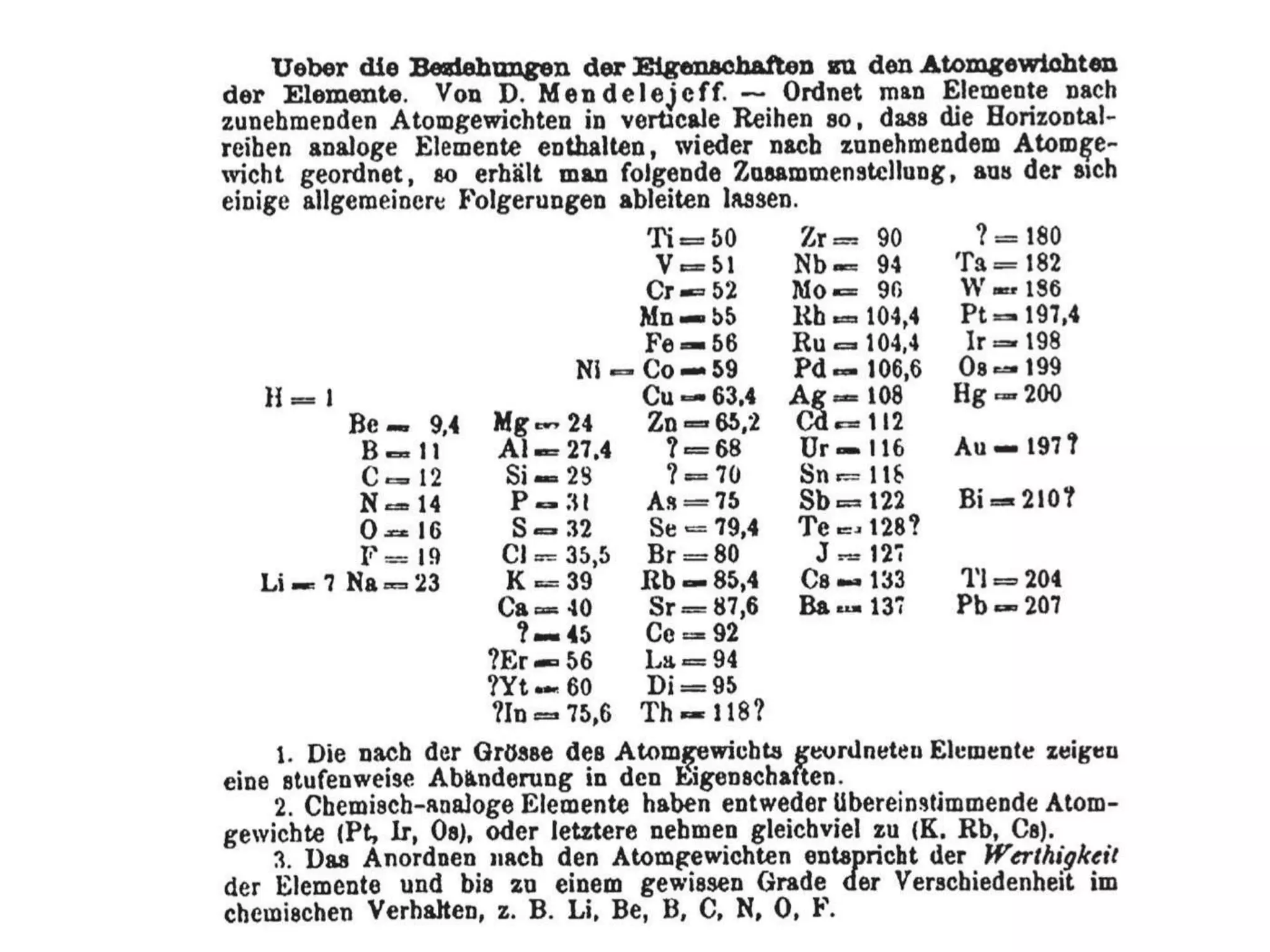

1) It summarizes the development of the periodic table from early Greek philosophers' attempts to classify elements to Mendeleev's breakthrough table in 1869 which brought order by organizing elements into groups with similar properties.

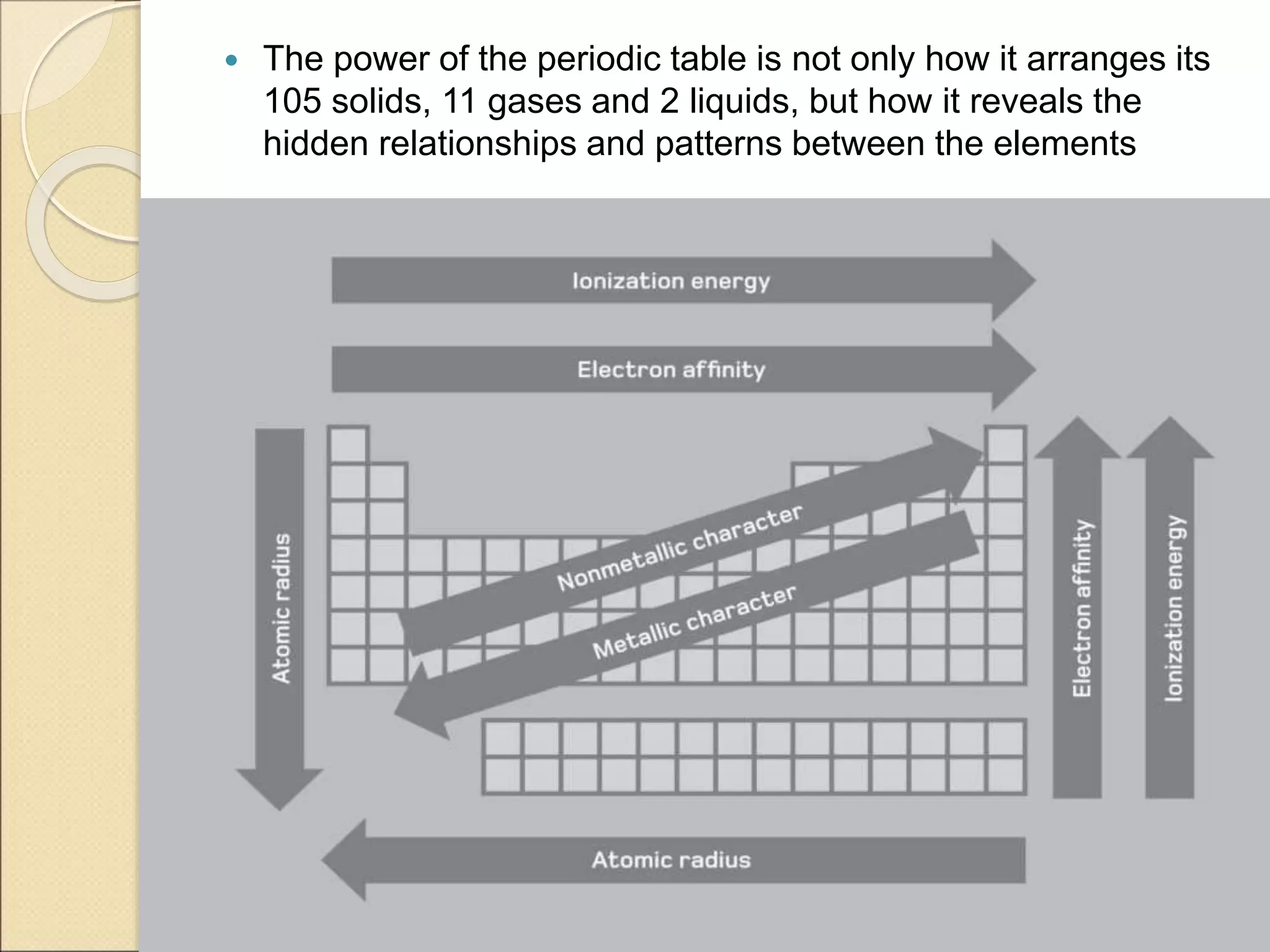

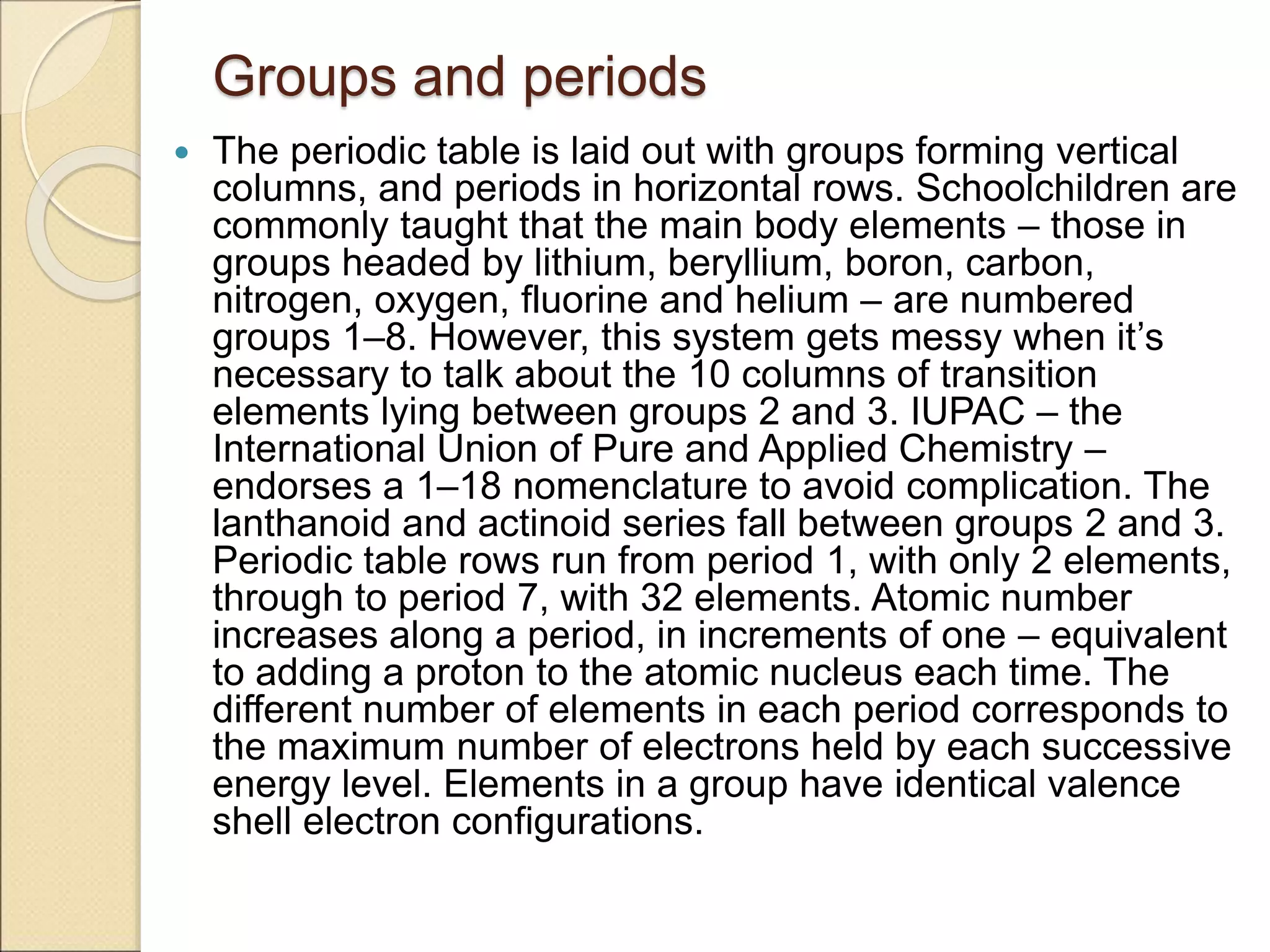

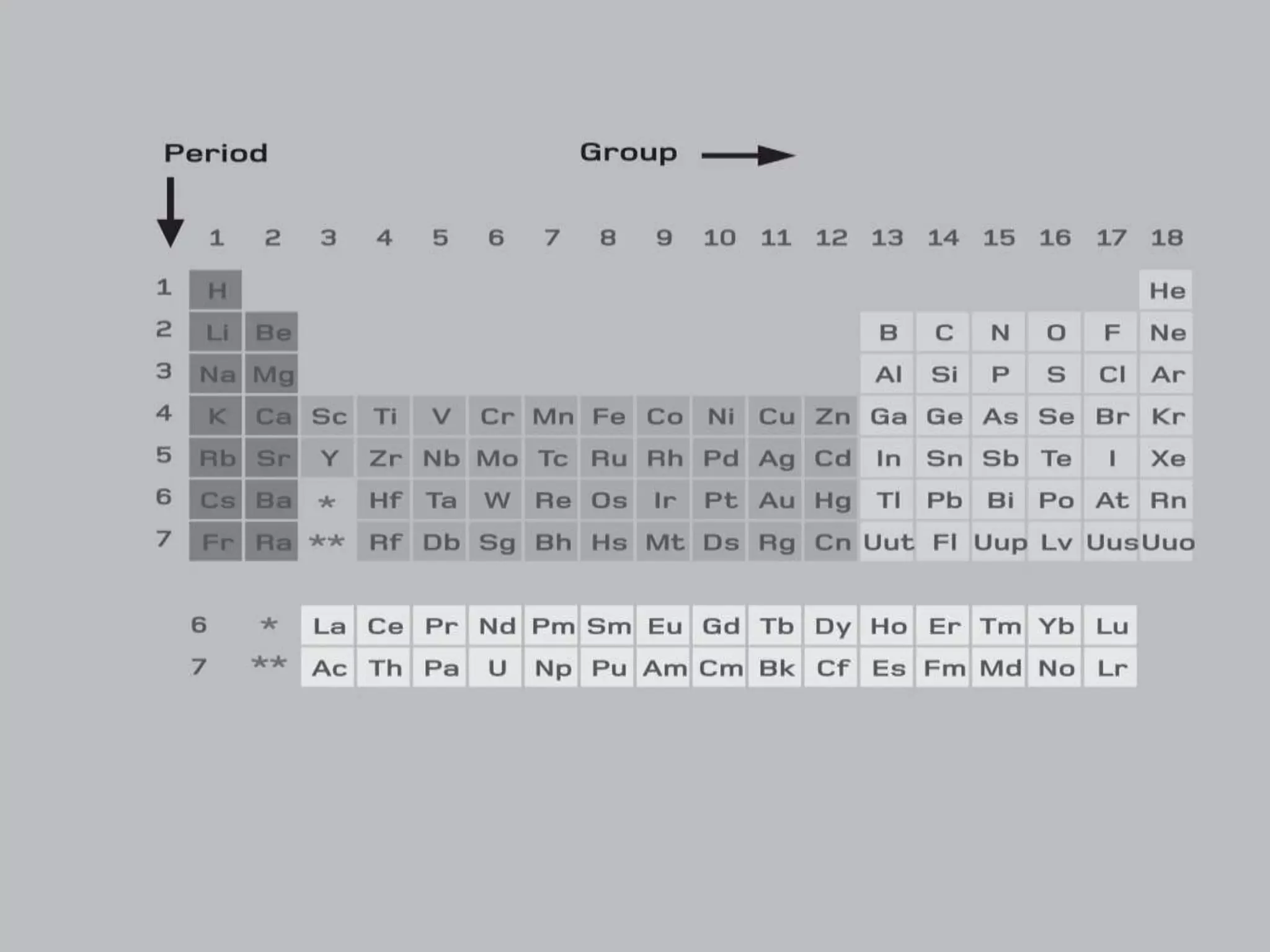

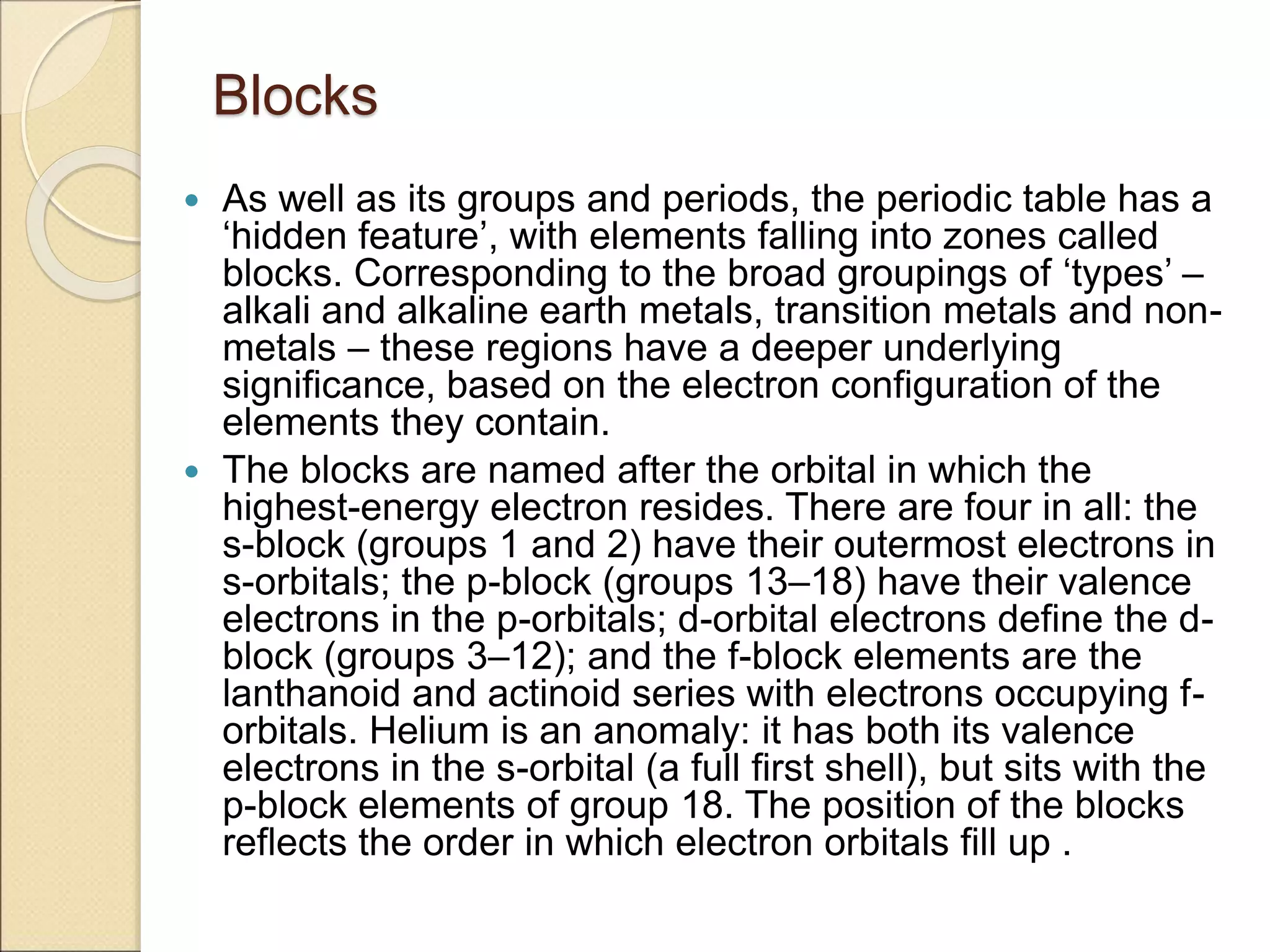

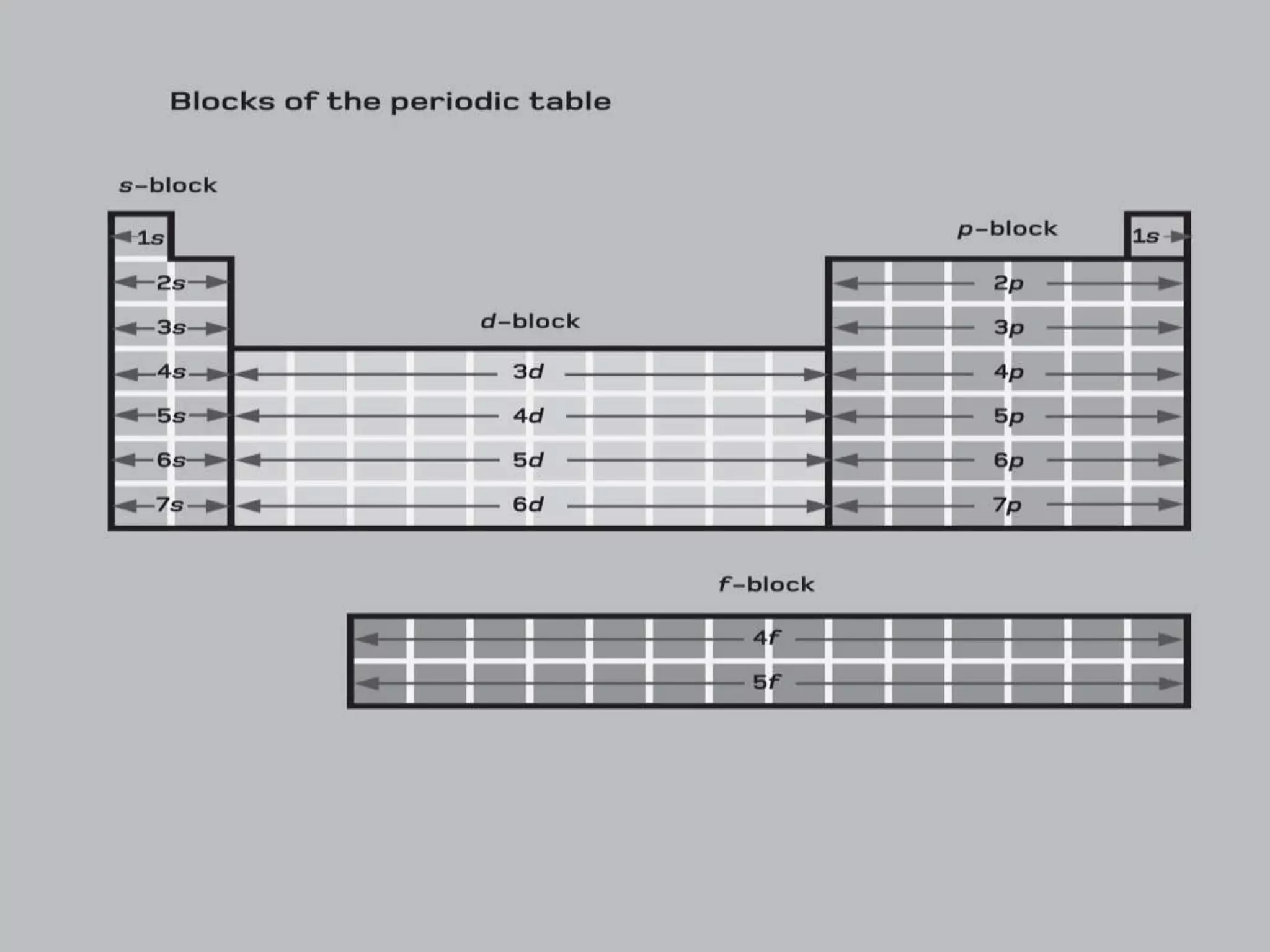

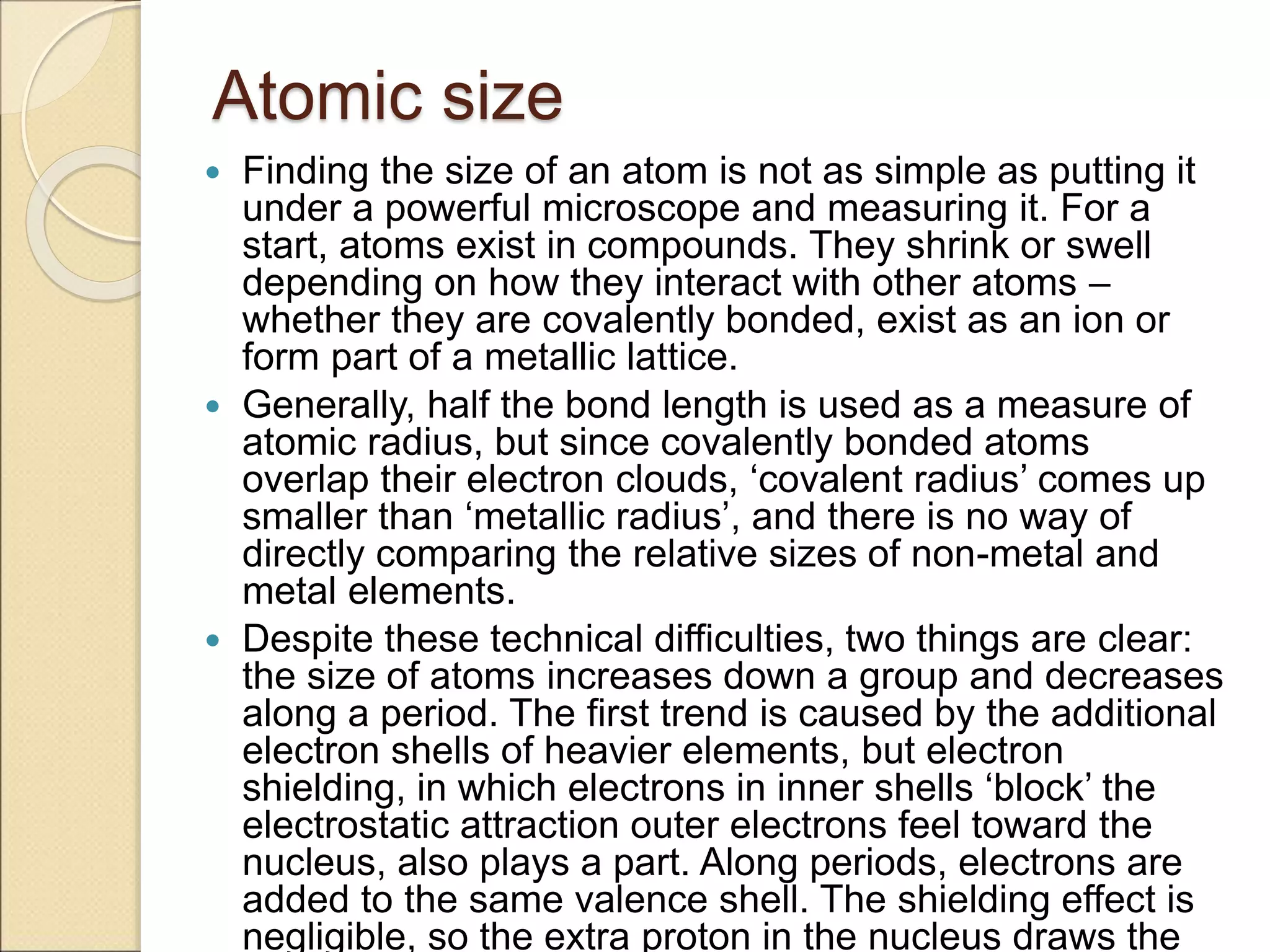

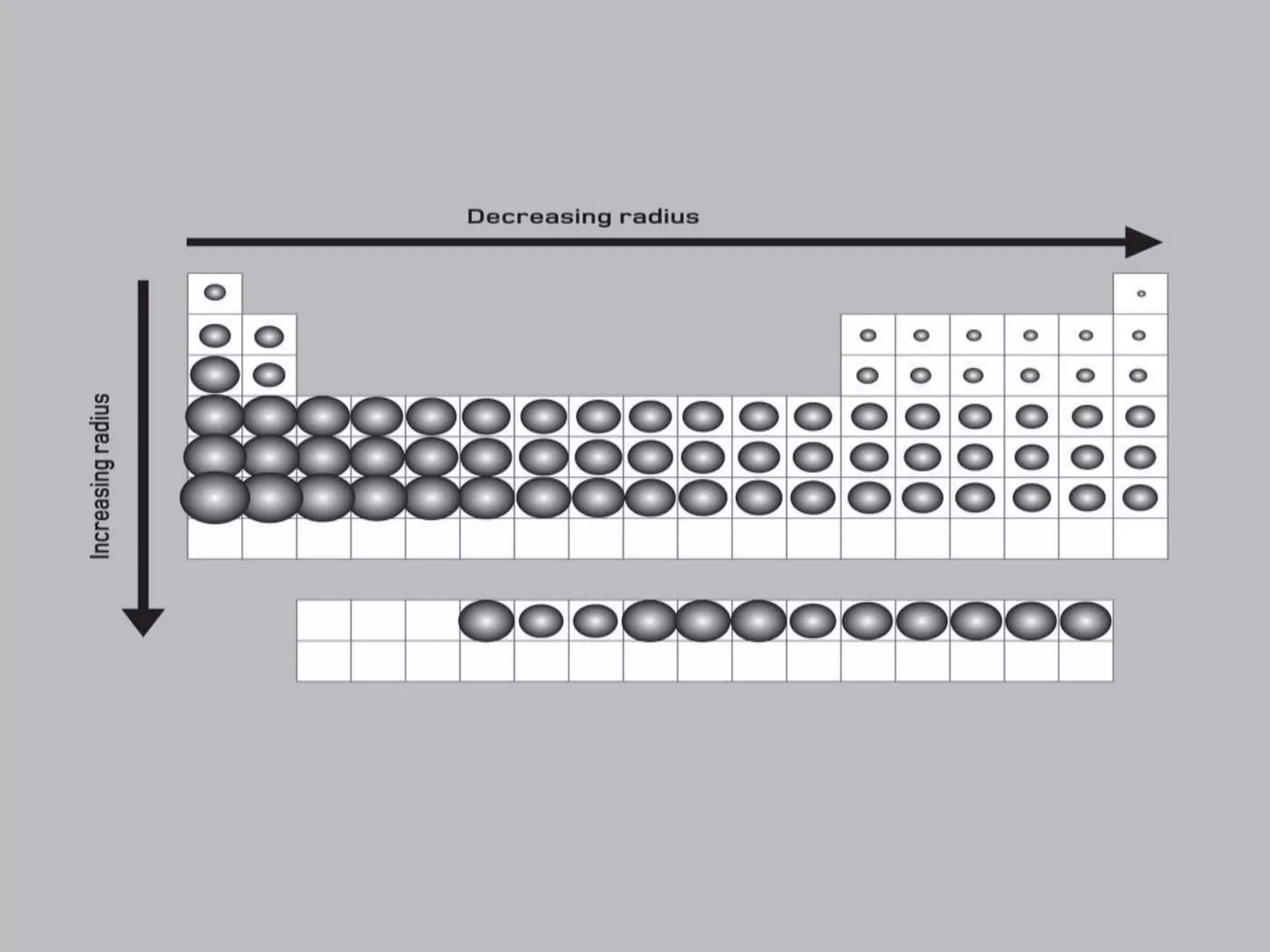

2) It describes key features of the periodic table including periods and groups, atomic size trends, melting/boiling point trends related to bond strength, and trends in electronegativity, ionization energy, and metallic character across the table.

3) It explains how the periodic table reveals relationships between elements and predicts missing or undiscovered elements, demonstrating its power to map the building blocks of matter.