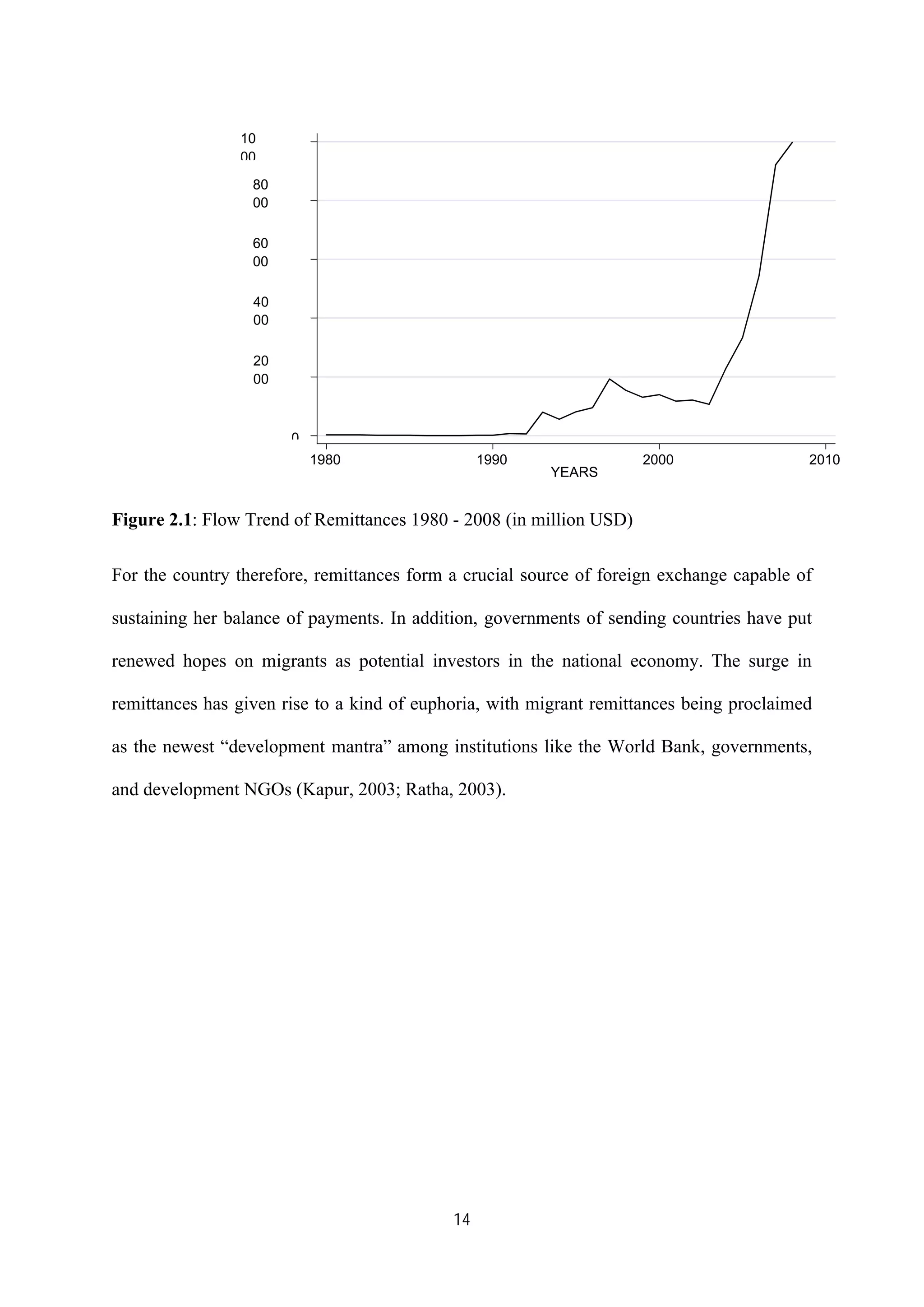

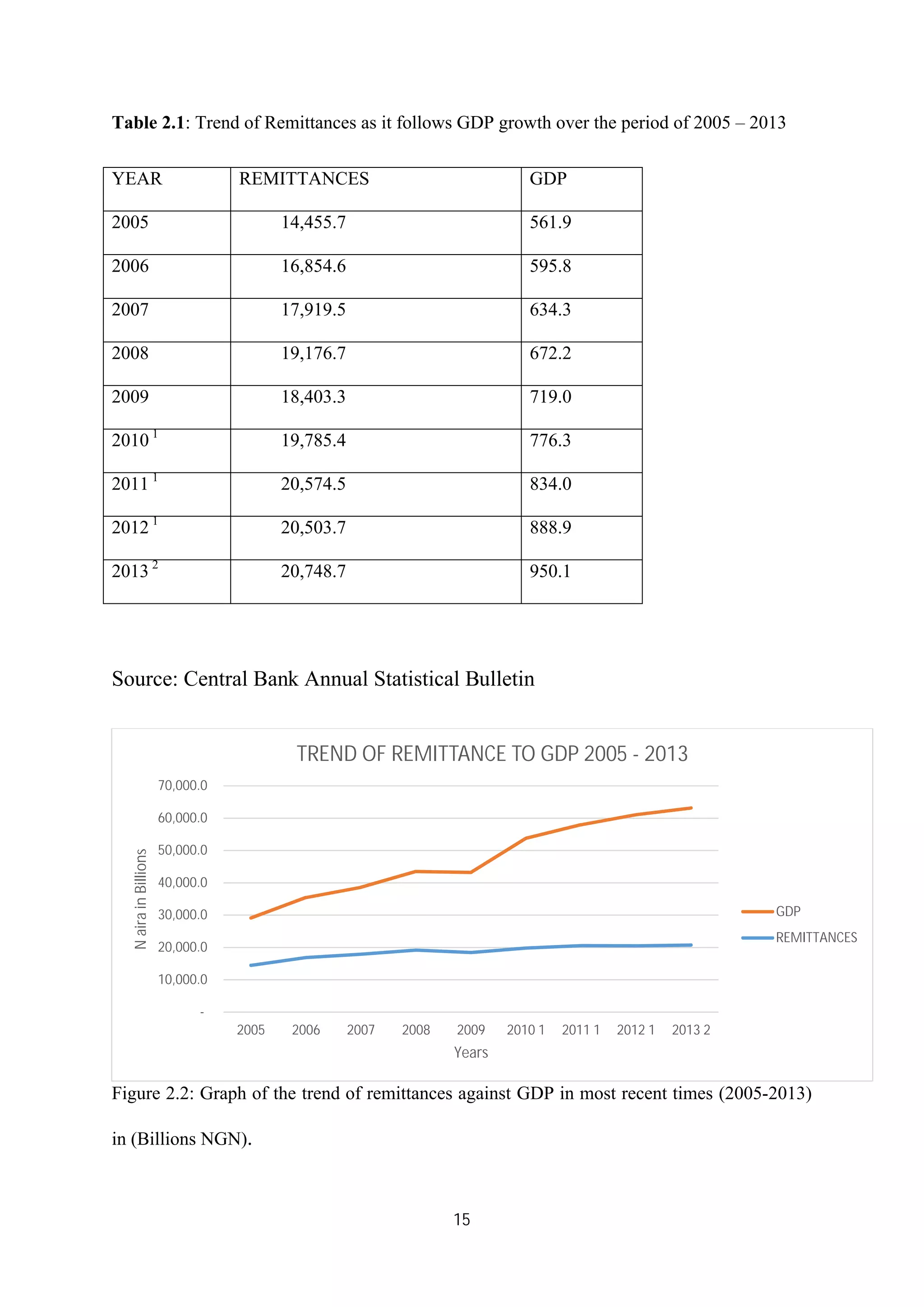

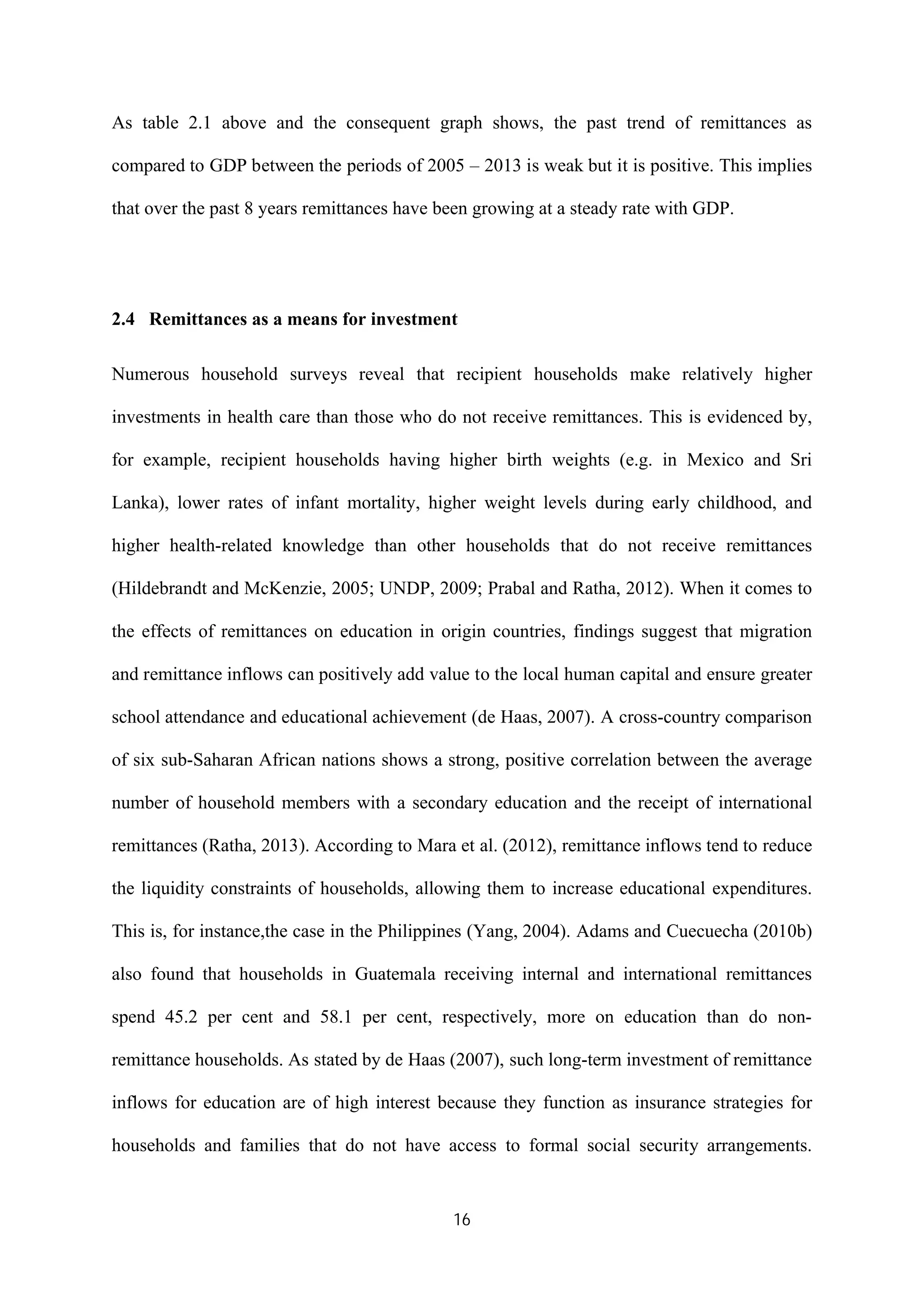

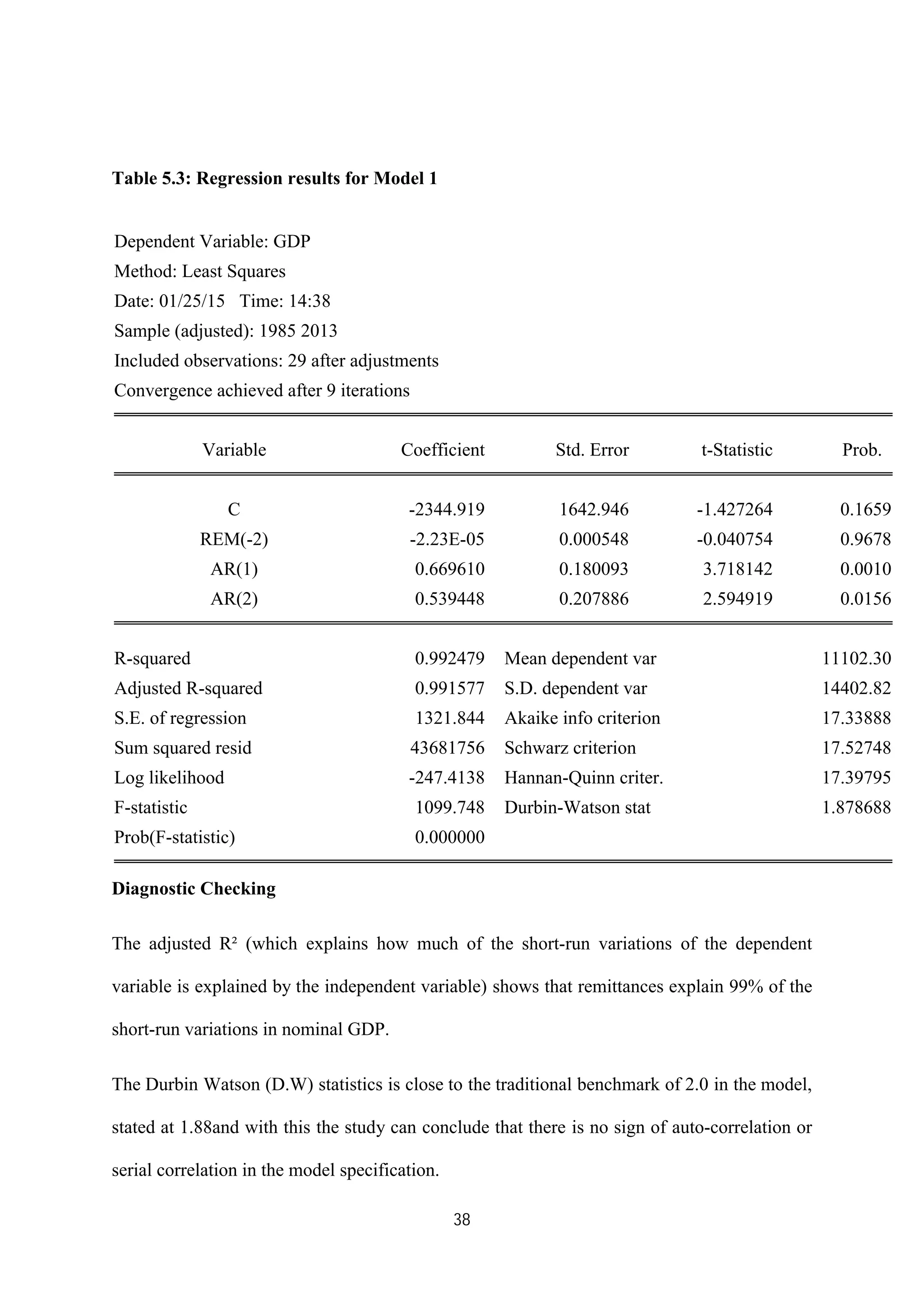

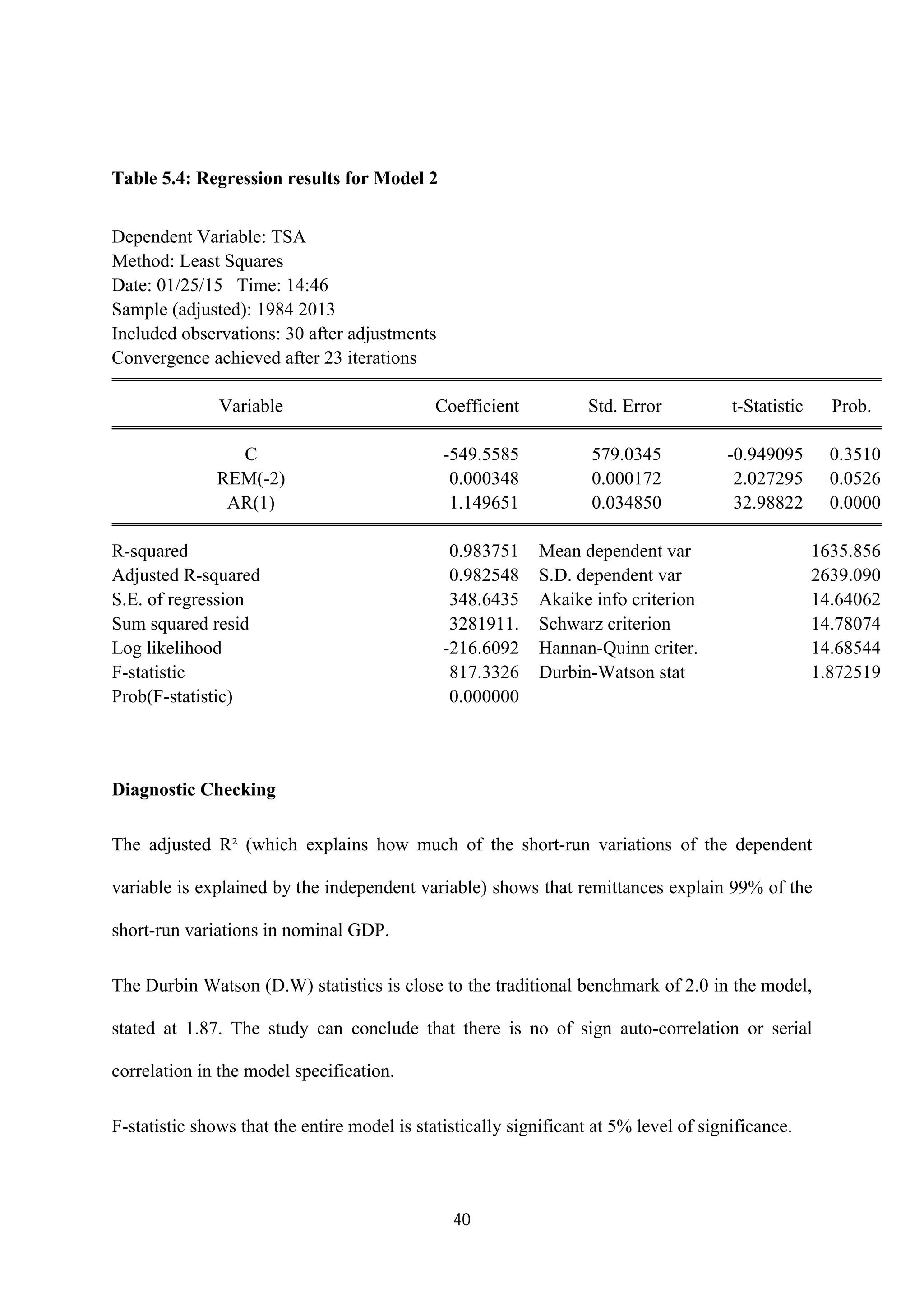

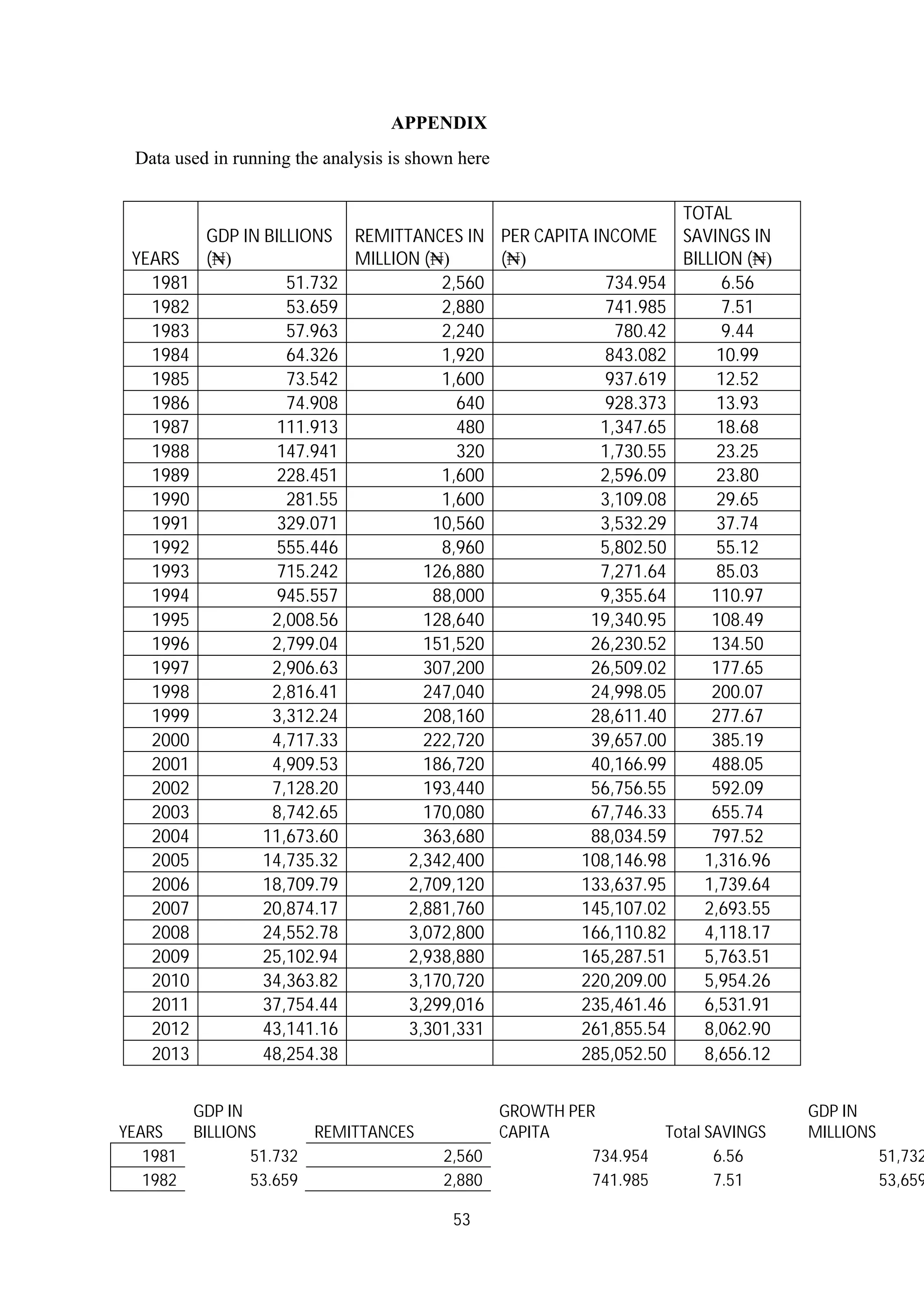

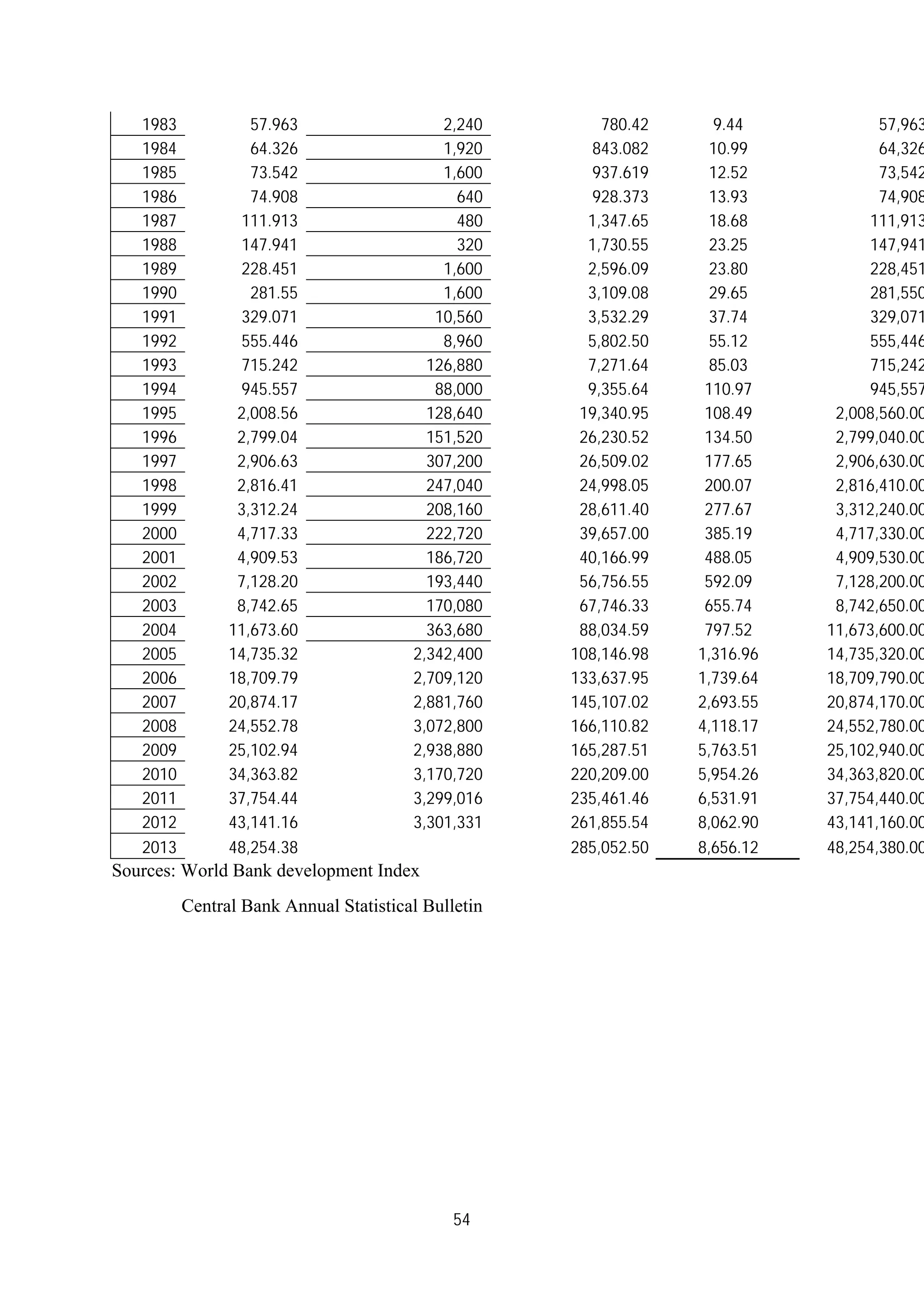

This document provides background information on migration and remittances in Nigeria. It discusses how migration in Nigeria includes both internal rural-urban migration as well as external emigration for opportunities and education abroad. Emigration increased Nigeria's net migration rate, with over 1 million Nigerian nationals living abroad as of 2007, most in neighboring countries but also in the US, UK, Italy and more. Remittances from these emigrants increased dramatically from $2.3 billion in 2004 to $17.9 billion in 2007 and $20.8 billion by 2013, outpacing foreign direct investment. The US, UK, Italy and other European and African countries are major sources of remittances to Nigeria.