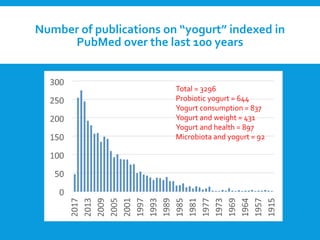

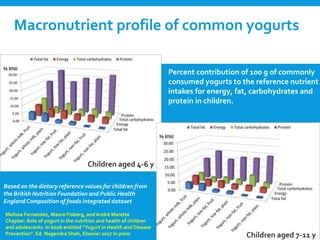

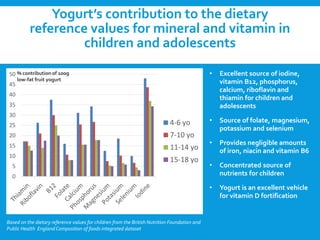

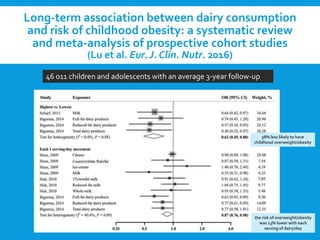

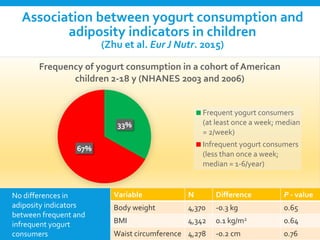

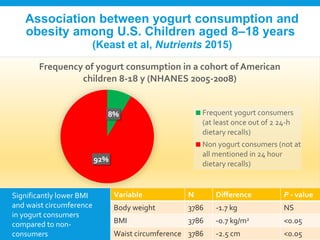

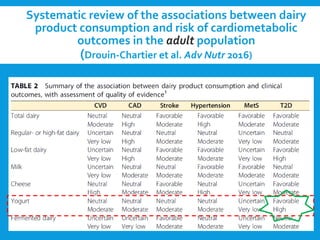

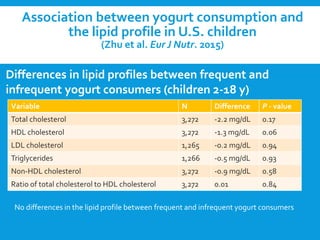

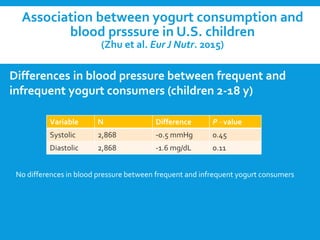

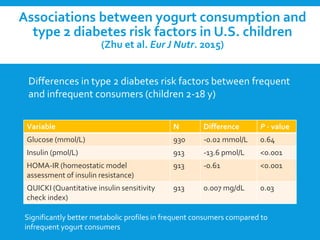

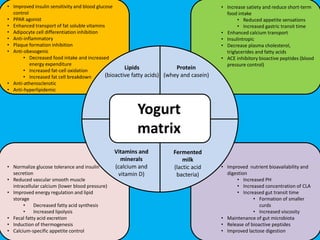

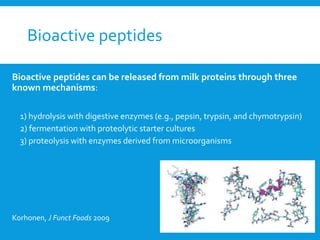

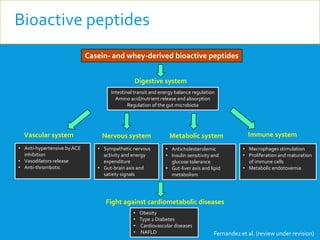

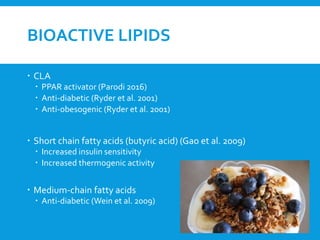

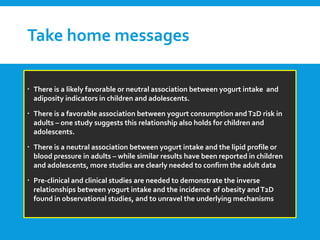

The document explores the potential associations between yogurt consumption and reduced cardiometabolic risk factors in children, highlighting its nutritional benefits such as high-quality protein, calcium, and bioactive compounds. Research indicates that yogurt may have a favorable or neutral impact on adiposity indicators and type 2 diabetes risk, while showing limited correlation with lipid profiles and blood pressure. Further studies are needed to clarify these relationships and understand the underlying mechanisms.