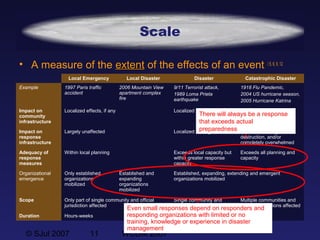

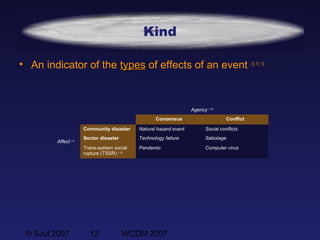

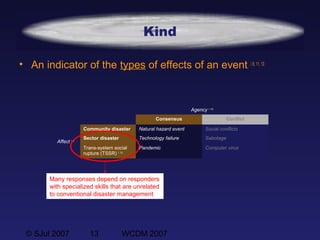

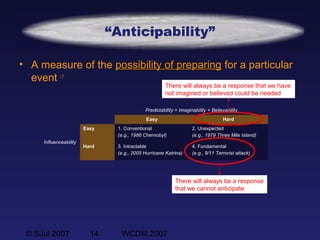

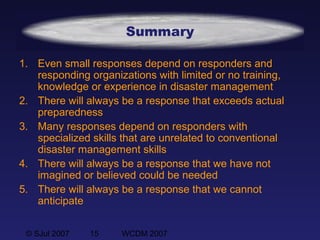

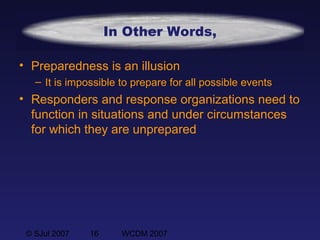

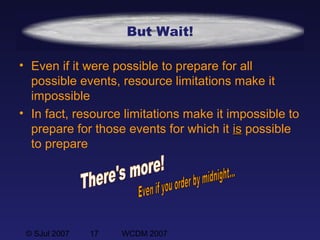

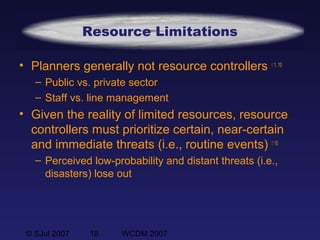

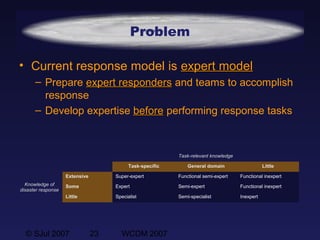

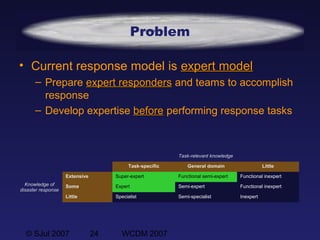

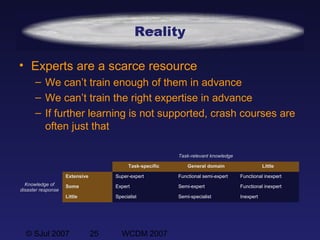

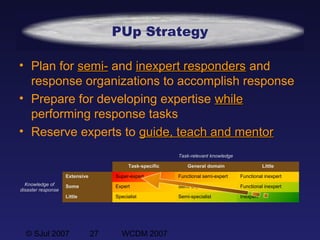

The document discusses the limitations of disaster preparedness, arguing that true preparedness is an illusion as it is impossible to account for all possible events. It highlights the necessity for responders to function in unanticipated situations and proposes strategies for leveraging available resources, including training semi-expert responders and co-sourcing tasks with non-disaster organizations. The challenges faced due to resource constraints and the unpredictability of disasters are emphasized throughout.