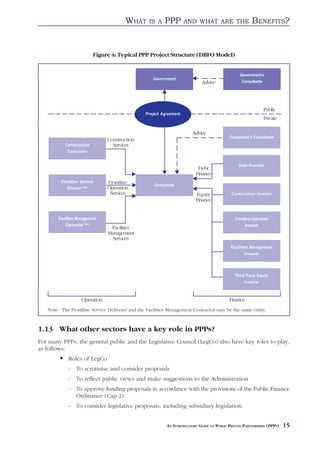

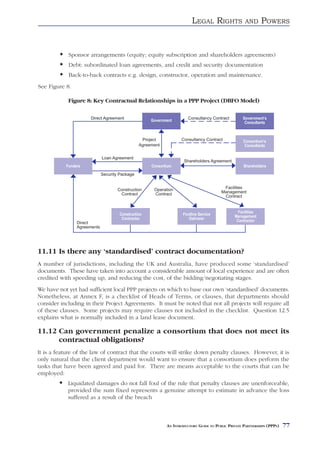

This document provides an introductory guide to public private partnerships (PPPs) in Hong Kong. It defines PPPs as long-term contractual arrangements between the public and private sectors to deliver public services. The guide discusses the benefits of PPPs, including enhancing and improving public services, realizing value for money, removing inefficiencies, and managing risks. It also outlines common PPP models and structures that are suitable for Hong Kong, such as design-build-finance-operate agreements. The key benefits of PPPs are bringing private sector efficiencies to public services and delivering better quality infrastructure and services at a lower overall cost than traditional procurement methods.