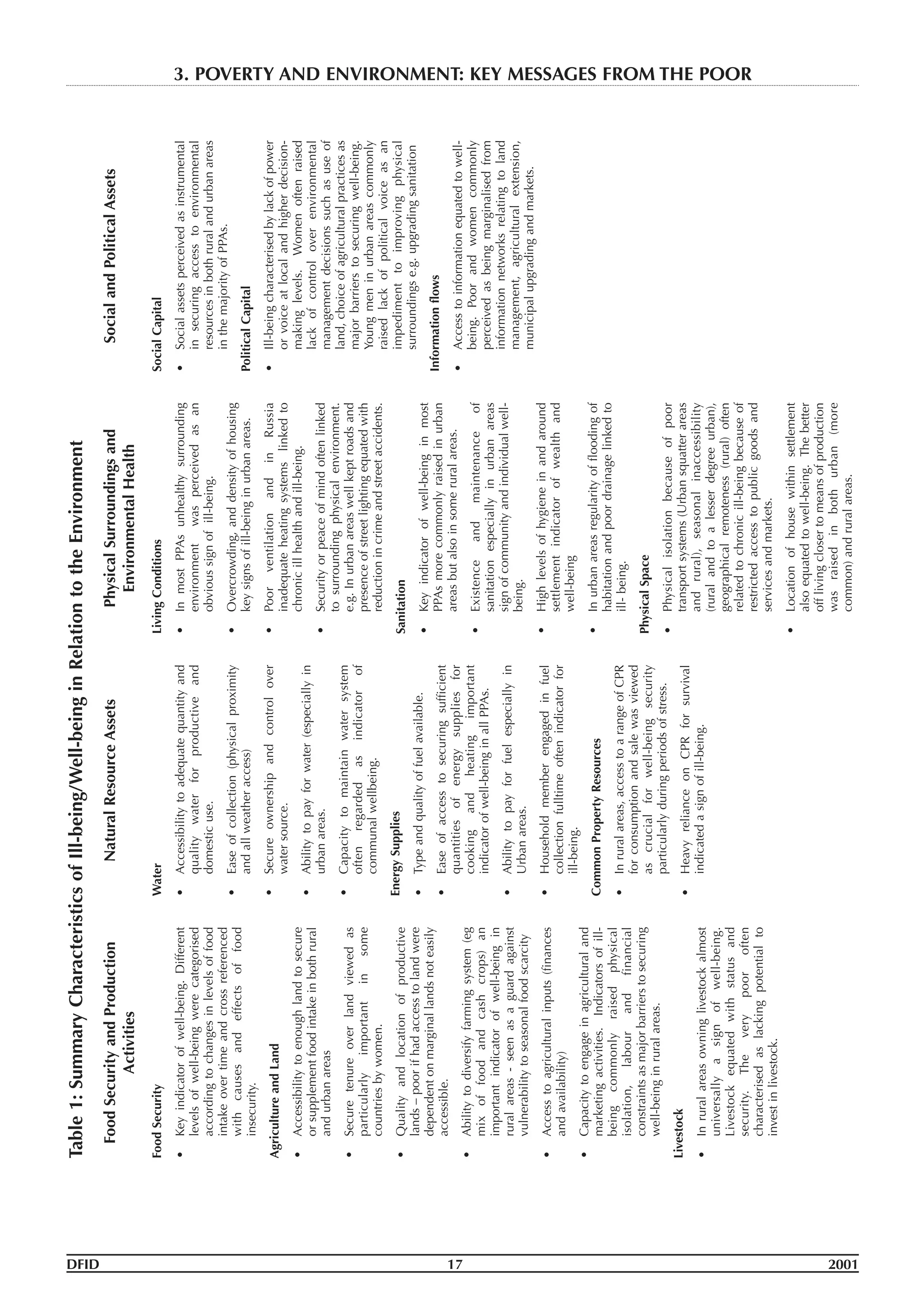

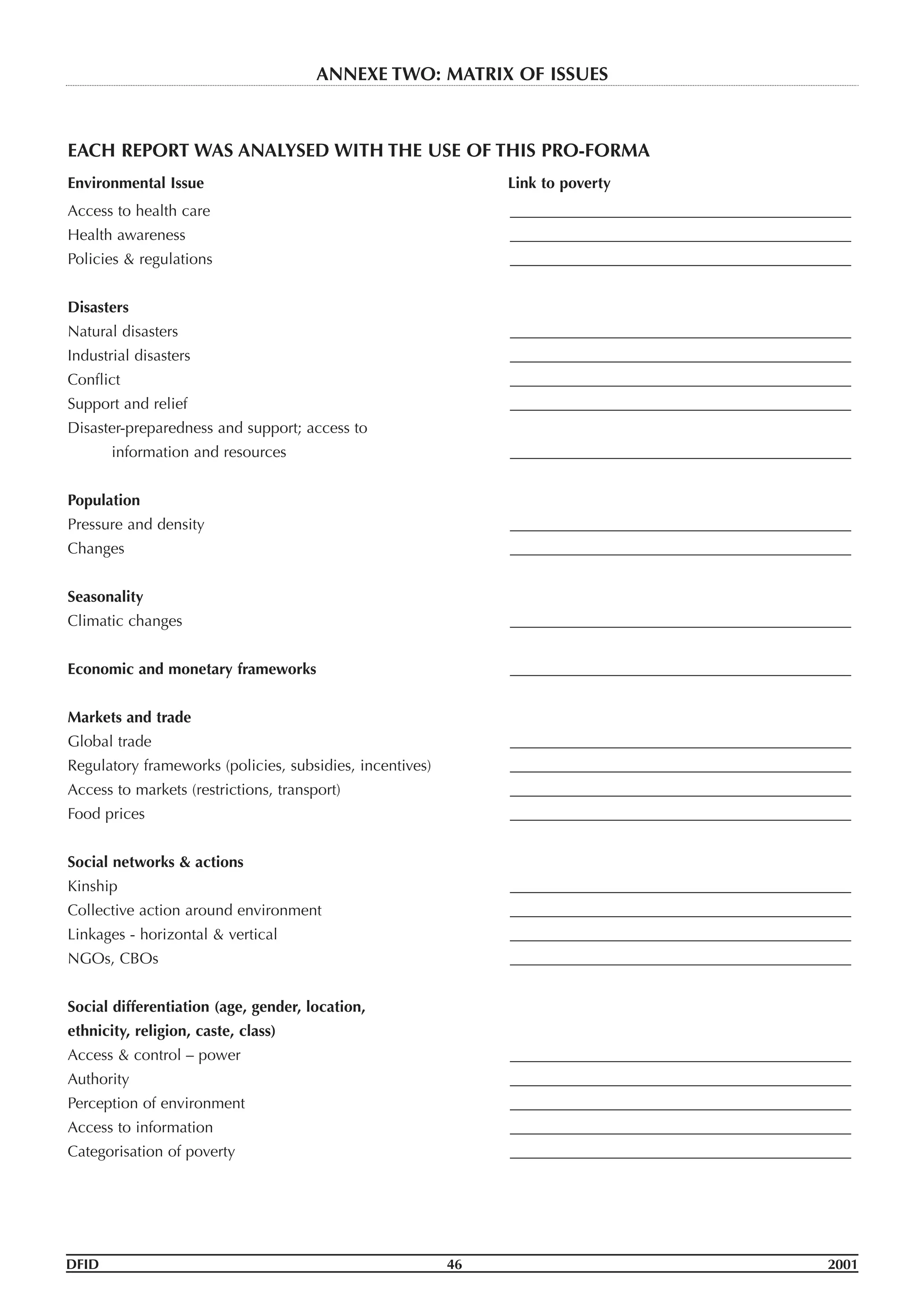

This document summarizes key findings from 23 Participatory Poverty Assessments across 14 countries regarding links between poverty and the environment from the perspective of poor people. Three main factors were found to determine how well poor people could use, maintain, and control their environmental resources: 1) The local environmental context, including fragile biophysical contexts, natural hazards, and environmental degradation; 2) Political and institutional contexts that marginalized the poor and biased markets and resource allocation against them; 3) How environmental shocks were experienced depended on people's ability to adapt their livelihood strategies, but this was limited by the first two factors.