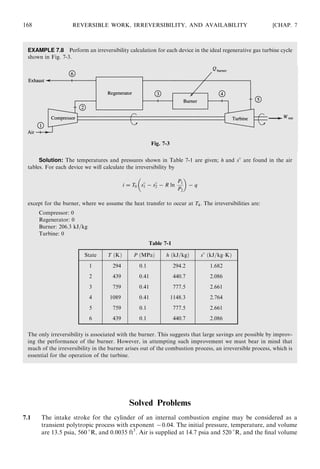

This document discusses reversible work, irreversibility, and availability in thermodynamics. It defines reversible work as the maximum possible work for a process, calculated by assuming the process is reversible with no entropy production. Irreversibility is defined as the difference between reversible and actual work. Availability is the maximum reversible work that can be extracted from a system as it moves to equilibrium with its surroundings. The document provides equations for calculating reversible work, irreversibility, and availability. It also introduces exergy as a measure analogous to availability. Several examples apply these concepts to problems involving turbines, compressors, and nozzles.

![where Wa is the actual work and Wrev is the reversible work for the fictitious reversible process. Second-

law efficiency is different from the adiabatic efficiency of a device introduced in Chap. 6. It is generally

higher and provides a better comparison to the ideal.

Second, irreversibility is defined as the difference between the reversible work and the actual work for

a process, or

I = Wrev − Wa ð7:3Þ

On a per-unit-mass basis,

i = wrev − wa ð7:4Þ

Both irreversibility and second-law efficiency will allow us to consider how close an actual process or

device is to the ideal. Once the irreversibilities for devices in an actual engineering system, such as a

steam power cycle, have been calculated, attempts to improve the performance of the system can be

guided by attacking the largest irreversibilities. Similarly, since the maximum possible work will be

reversible work, irreversibility can be used to evaluate the feasibility of a device. If the irreversibility

of a proposed device is less than zero, the device is not feasible. [Section 7.2 develops the concepts of

reversible work and irreversibility.]

Availability is defined as the maximum amount of reversible work that can be extracted from a

system:

É = ðWrevÞmax ð7:5Þ

or, on a per-unit-mass basis,

= ðwrevÞmax ð7:6Þ

The maximization in (7.5) and (7.6) is over the reversible path joining the prescribed initial state to a final

dead state in which system and surroundings are in equilibrium. [Section 7.3 develops the notion of

availability.]

7.2 REVERSIBLE WORK AND IRREVERSIBILITY

To obtain expressions for reversible work and irreversibility, we will consider a transient process

with specified work output and heat input and a uniform through-flow. We begin by allowing this to be

an irreversible process. Consider the control volume shown in Fig. 7-1. The first law for this control

volume can be written as

_Q − _WS = h2 +

V 2

2

2

+ gz2

!

_m2 − h1 +

V 2

1

2

+ gz1

!

_m1 + _Ec:v: ð7:7Þ

Using (6.47), with Tsurr = T0 and _Qsurr = − _Q, we may write the second law as

_Sc:v: + s2 _m2 − s1 _m1 −

_Q

T0

− _Sprod = 0 ð7:8Þ

Eliminate _Q between (7.7) and (7.8) to obtain

_WS = − _Ec:v: + T0

_Sc:v: − h2 +

V 2

2

2

+ gz2 − T0s2

!

_m2

+ h1 +

V 2

1

2

+ gz1 − T0s1

!

_m1 − T0

_Sprod

ð7:9Þ

162 REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY [CHAP. 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-1-320.jpg)

![Since _Sprod is due to the irreversibilities, the reversible work rate is given by (7.9) when _Sprod is set equal to zero:

_Wrev = − _Ec:v: + T0

_Sc:v: − h2 +

V 2

2

2

+ gz2 − T0s2

!

_m2 + h1 +

V 2

1

2

+ gz1 − T0s1

!

_m1 ð7:10Þ

Then a time integration yields

Wrev = mi ui +

V 2

i

2

+ gzi − T0si

!

− mf uf +

V 2

f

2

+ gzf − T0sf

!" #

c:v:

:

+ m1 h1 +

V 2

1

2

+ gz1 − T0s1

!

− m2 h2 +

V 2

2

2

+ gz2 − T0s2

! ð7:11Þ

where the subscripts i and f pertain to the initial and final states of the control volume.

The actual work, if not given, can be determined from a first-law analysis:

Wa = mi ui +

V 2

i

2

+ gzi

!

− mf uf +

V 2

f

2

+ gzf

!" #

c:v:

+ m1 h1 +

V 2

1

2

+ gz1

!

− m2 h2 +

V 2

2

2

+ gz2

!

+ Q

ð7:12Þ

From (7.3), (7.11), and (7.12),

I = ðmf T0sf − miT0siÞc:v: + T0m2s2 − T0m1s1 − Q ð7:13Þ

For a steady flow with negligible changes in kinetic and potential energies, we have

_Wrev = _m½h1 − h2 + T0ðs2 − s1ÞŠ ð7:14Þ

_I = _mT0ðs2 − s1Þ + _Q ð7:15Þ

It is important to realize that the basic results of this Section—(7.11), (7.12), and (7.13)—also hold

for a system, which is nothing other than a control volume for which m1 = m2 = 0 (and thus

mi = mf = m). Because time plays no part in the thermodynamics of a system, we generally replace

the indices i and f by 1 and 2.

EXAMPLE 7.1 An ideal steam turbine is supplied with steam at 12 MPa and 700

C, and exhausts at 0.6 MPa.

(a) Determine the reversible work and irreversibility.

(b) If the turbine has an adiabatic efficiency of 0.88, what is the reversible work, irreversibility, and second-law

efficiency?

CHAP. 7] REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY 163

Fig. 7-1 The control volume used in the second-law analysis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-2-320.jpg)

![In carrying out a second-law analysis, it is often useful to define a new thermodynamic function

(analogous to enthalpy), called exergy:

E h +

V 2

2

+ gz − T0s ð7:18Þ

Comparing (7.18) to (7.17), we see that E1 − E0 = . We interpret this equation as a work-energy

relation: the extractable specific work exactly equals the decrease in useful exergy E between the

entrance and dead states of the system. More generally, when the system passes from one state to

another, specific work in the amount −ÁE is made available.

Certain engineering devices have useful outputs or inputs that are not in the form of work; a nozzle

is an example. Consequently, we generalize the notion of second-law efficiency to that of second-law

effectiveness:

II =

ðavailability producedÞ + ðwork producedÞ + ðadjusted heat producedÞ

ðavailability suppliedÞ + ðwork usedÞ + ðadjusted heat usedÞ

ð7:19Þ

Heat to or from a device is ‘‘adjusted’’ in (7.19) on the basis of the temperature −Th:r: of the heat

reservoir which is interacting with the device:

adjusted heat = 1 −

T0

Th:r:

Q ð7:20Þ

EXAMPLE 7.3 Which system can do more useful work, 0.1 lbm of CO2 at 440

F and 30 psia or 0.1 lbm of N2

at 440

F and 30 psia?

Solution: Assuming a dead state at 77

F (537

R) and 14.7 psia, we use Table E-4E to calculate the

availability of the CO2:

É = m h − h0 − T0 s

1 − s

0 − R ln

P

P0

!

=

0:1

44

7597:6 − 4030:2 − 537 56:070 − 51:032 − 1:986 ln

30

14:7

!

= 3:77 Btu

Similarly, for the N2,

É = m h − h0 − T0 so

1 − so

0 − R ln

P

P0

!

=

0:1

28

6268:1 − 3279:5 − ð537Þ 49:352 − 45:743 − 1:986 ln

30

14:7

!

= 6:47 Btu

Hence, the N2 can do more useful work.

EXAMPLE 7.4 How much useful work is wasted in the condenser of a power plant which takes in steam of

quality 0.85 and 5 kPa and delivers saturated liquid at the same pressure?

Solution: The maximum specific work available at the condenser inlet is 1 = h1 − h0 − T0ðs1 − s0Þ; at

the outlet it is 2 = h2 − h0 − T0ðs2 − s0Þ. The useful work wasted is 1 − 2 = h1 − h2 − T0ðs1 − s2Þ.

From the steam tables, assuming T0 = 298 K and using the quality to find h1 and s1, we find

1 − 2 = h1 − h2 − T0ðs1 − s2Þ = 2197:2 − 136:5 − ð298Þð7:2136 − 0:4717Þ = 51:6 kJ=kg

CHAP. 7] REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY 165](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-4-320.jpg)

![Comparing to sf and sg at 0.1 MPa, we have a two-phase mixture at state 2 with

x2 =

s2 − sf

sfg

= 0:96

so that h2 = hf + 0:96hfg = 2587:3 kJ/kg.

2 ! 3 Ideal turbine: s3 = s2 = 7:1237 kJ=kgÁK

Comparing to sf and sg at 0.01 MPa, we have a two-phase mixture at state 3 with

x3 =

s3 − sf

sfg

= 0:86

so that h3 = hf + 0:86hfg = 2256:9 kJ=kg. The second-law effectiveness is given by

II =

É2 + Wturb

É4 + Wpump + ½1 − ðT0=T1ÞŠQboil

The dead state for water is liquid at 100 kPa and 25

C:

h0 = hf = 104:9 kJ=kg s0 = sf = 0:3672 kJ=kgÁK

Now the various quantities of interest may be calculated, assuming m1 = 1 kg:

É2 = m2½h2 − h0 − T0ðs2 − s0ÞŠ = ð0:1Þ½2587:3 − 104:9 − ð298Þð7:1237 − 0:3672ÞŠ = 46:89 kJ

Wturb = m1ðh1 − h2Þ + m3ðh2 − h3Þ = ð1:0Þð3051:2 − 2587:3Þ + ð0:9Þð2587:3 − 2256:9Þ = 761:3 kJ

É4 = m4½h4 − h0 − T0ðs4 − s0ÞŠ = ð0:1Þ½191:8 − 104:9 − ð298Þð0:6491 − 0:3671ÞŠ = 0:28 kJ

Wpump = m1

ÁP

= ð1:0Þ

1000 − 10

1000

= 0:99 kJ Qboil = m1ðh1 − h6Þ = ð1:0Þð3051:2 − 192:8Þ = 2858 kJ

whence

II =

46:89 + 761:3

0:28 + 0:99 + ð1 − 298=573Þð2858Þ

= 0:59

CHAP. 7] REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY 167

Fig. 7-2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-6-320.jpg)

![and temperature are 0.025 ft3

and 520

R. Determine the reversible work and the irreversibility

associated with the intake process.

At the various states either we are given, or the air tables provide, the values shown in Table 7-2. In the

initial state,

mi =

PiVi

RTi

=

ð13:5Þð144Þð0:0035Þ

ð53:3Þð560Þ

= 2:28 Â 10−4

lbm

The final state is produced by a polytropic process, so that

Pf = Pi

Vi

Vf

n

= ð13:5Þ

0:0035

0:025

−0:04

= 14:6 psia

mf =

Pf Vf

RTf

=

ð14:6Þð144Þð0:025Þ

ð53:3Þð520Þ

= 1:90 Â 10−3

lbm

From conservation of mass, m1 = mf − mi = ð1:90 Â 103

Þ − ð2:28 Â 10 −4

Þ = 1:67 Â 10−3

lbm. Only bound-

ary work is actually performed; for the polytropic process we have

Wa =

Pf Vf − PiVi

1 − n

=

½ð14:6Þð0:025Þ − ð13:5Þð0:0035ÞŠð144Þ

ð1 + 0:04Þð778Þ

= 0:057 Btu

The reversible work is given by (7.11) (neglect KE and PE, as usual):

Wrev = miðui − T0siÞ − mf ðuf − T0sf Þ + m1ðh1 − T0s1Þ

The needed values of si and sf are obtained from the ideal-gas relation

s = s

− R ln

P

P0

where P0 is some reference pressure. Normally, we do not have to worry about P0, since when we consider an

entropy change, P0 cancels. It can be shown that even for this problem it will cancel, so that

Wrev = miðui − T0s

i + T0R ln PiÞ − mf ðuf − T0s

f + T0R ln Pf Þ

+m1ðh1 − T0s

1 + T0R ln P1Þ = 0:058 Btu

and, finally, I = Wrev − Wa = 0:058 − 0:057 = 0:001 Btu.

7.2 A supply pump for a power plant takes in saturated water at 0.01 MPa and boosts its pressure to

10 MPa. The pump has an adiabatic efficiency of 0.90. Calculate the irreversibility and second-

law efficiency.

At the inlet and exit states either we are given, or the steam tables provide, the values given in Table 7-3.

The actual work is

wa =

wideal

= −

ÁP

= −

10 000 − 10

ð0:9Þð1000Þ

= −11:1 kJ=kg

CHAP. 7] REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY 169

Table 7-2

Inlet State Initial State of C.V. Final State of C.V.

T1 = 520

R Ti = 560

R Tf = 520

R

P1 = 14:7 psia Pi = 13:5 psia uf = 88:62 Btu=lbm

h1 = 124:27 Btu=lbm ui = 95:47 Btu=lbm s

f = 0:5917 Btu=lbm-

R

s

1 = 0:5917 Btu=lbm-

R s

i = 0:6095 Btu=lbm-

R Vf = 0:025 ft3

Vi = 0:0035 ft3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-8-320.jpg)

![7.5 A feedwater heater extracts steam from a turbine at 600 kPa and 250

C which it combines with

0.3 kg/s of liquid at 600 kPa and 150

C. The exhaust is saturated liquid at 600 kPa. Determine

the second-law effectiveness of the heater.

For data, see Table 7-5. By conservation of mass, _m3 = _m1 + _m2. Then, the first law demands

_m3h3 = _m1h1 + _m2h2. Solving simultaneously for _m1 and _m3:

_m1 = 0:00504 kg=s _m3 = 0:305 kg=s

The second-law effectiveness is II = _É3=ð _É1 + _É2Þ. Taking the dead state as liquid water at 25

C and

100 kPa, we have

h0 = 105 kJ=kg s0 = 0:3672 kJ=kgÁK

Then

_É3 = _m½h3 − h0 − T0ðs3 − s0ÞŠ = ð0:305Þ½670:6 − 105 − 298ð1:9316 − 0:3672ÞŠ = 30:33 kW

_É1 = _m1½h1 − h0 − T0ðs1 − s0ÞŠ = ð0:00504Þ½2957:2 − 105 − 298ð7:1824 − 0:3672ÞŠ = 4:14 kW

_É2 = _m2½h2 − h0 − T0ðs2 − s0ÞŠ = ð0:30Þ½632:2 − 105 − 298ð1:8422 − 0:3672ÞŠ = 23:63 kW

and

II =

30:33

4:14 + 23:63

= 1:09

7.6 Consider the ideal refrigeration cycle shown in Fig. 7-4 which utilizes R134a. The condenser

operates at 800 kPa while the evaporator operates at 120 kPa. Calculate the second-law effec-

tiveness for the cycle.

The given values and the R134a tables in Appendix D allow us to set up Table 7-6.

CHAP. 7] REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY 171

Table 7-5

Inlet state 1: superheated vapor Inlet state 2: compressed liquid Exit state 3: saturated liquid

T = 250

C T = 150

C P = 0:6 MPa

P = 0:6 MPa P = 0:6 MPa T = 158:9

C

h = 2957:2 h = 632:2 kJ=kg h = 670:6 kJ=kg

s = 7:1824 kJ=kgÁK s = 1:8422 kJ=kgÁK s = 1:9316 kJ=kgÁK

Fig. 7-4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-10-320.jpg)

![7.14 Ideally, which fluid can do more work: air at 600 psia and 600

F or steam at 600 psia and 600

F?

7.15 A piston-cylinder system with air undergoes a polytropic compression with n = 1:1 from 75

F, 15 psia, and

0.2 liter to 0.04 liter. Determine (a) actual work, (b) heat transfer, (c) reversible work, and (d) irreversibility.

7.16 Methane gas at 800 K and 3 MPa is contained in a piston-cylinder system. The system is allowed to expand

to 0.1 MPa in a polytropic process with n = 2:3. What is the second-law efficiency of the process?

7.17 Argon is contained in a sealed tank of 10 liters at 400 psia and 50

F. What is the maximum work the argon

can do on earth at 536

R?

7.18 A rigid tank initially contains 0.5 lbm of R134a as saturated liquid at 30 psia. It is then allowed to come to

equilibrium with its surroundings at 70

F. Determine (a) the final state of the refrigerant and (b) the

irreversibility.

7.19 Air enters a compressor at 100 kPa and 295 K and exits at 700 kPa and 530 K with 40 kJ=kg of heat transfer

to the surroundings. Determine (a) reversible work, (b) irreversibility, and (c) second-law efficiency for the

compressor.

7.20 A compressor with an adiabatic efficiency of 90 percent intakes air at 500

R and 15 psia and exhausts at 120

psia. Determine (a) the actual work and (b) the reversible work associated with this compressor.

7.21 The evaporator for an air-conditioning system is a heat exchanger. R134a enters at 0.05 kg=s and −20

C as

saturated liquid and leaves as saturated vapor. Air enters at 34

C and leaves at 18

C. (a) What is the mass

flow rate of air? (b) What is the irreversibility rate of the evaporator?

7.22 A direct contact heat exchanger serves as the condenser for a steam power plant. Steam with quality of 50

percent at 100 kPa flows into the mixing tank at 2 kg/s. Groundwater at 10

C and 100 kPa is available to

produce saturated liquid flowing out of the mixing tank. The mixing tank is well-insulated. Determine (a) the

mass flow rate of groundwater required and (b) the irreversibility rate.

7.23 Steam is throttled across an adiabatic valve from 250 psia and 450

F to 60 psia. Determine (a) the reversible

work and (b) the irreversibility.

7.24 It has been proposed to utilize a nozzle in conjunction with a wind turbine system. Air enters the adiabatic

nozzle at 9 m/s, 300 K, and 120 kPa and exits at 100 m/s and 100 kPa. Determine (a) the irreversibility and

(b) the reversible work.

7.25 In the burner for a gas turbine system 0.2 lbm/sec of air at 20 psia and 900

R is heated to 2150

R in a

constant-pressure process while hot combustion gases (assumed to be air) are cooled from 3000

R to

2400

R. What is the irreversibility rate of this process?

7.26 Saturated water enters an adiabatic pump at 10 kPa and exits at 1 MPa. If the pump has an adiabatic

efficiency of 95 percent, determine (a) the reversible work and (b) the second-law efficiency.

7.27 The pressure of water is increased, by the use of a pump, from 14 to 40 psia. A rise in the water temperature

from 60

F to 60.1

F is observed. Determine (a) the irreversibility, (b) the reversible work, and (c) the

adiabatic efficiency of the pump.

7.28 Air at 2200

R and 40 psia enters a gas turbine with an adiabatic efficiency of 75 percent and exhausts at 14.7

psia. Determine (a) the availability of the exhaust air and (b) the reversible work.

CHAP. 7] REVERSIBLE WORK, IRREVERSIBILITY, AND AVAILABILITY 173](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-12-320.jpg)

![assuming an ideal gas with constant specific heat. For an isentropic compression between inlet and outlet

we know that

T2 = T1

P2

P1

ðk−1Þ=k

ð8:4Þ

This allows the work to be expressed as, using Cp given in (4.30),

wcomp =

kR

k−1

T1

P2

P1

ðk−1Þ=k

− 1

#

ð8:5Þ

For a polytropic process we simply replace k with n and obtain

wcomp =

nR

n − 1

T1

P2

P1

ðn−1Þ=n

− 1

#

ð8:6Þ

The heat transfer is then found from the first law.

By external cooling, with a water jacket surrounding the compressor, the value of n when compres-

sing air can be reduced to about 1.35. This reduction from 1.4 is difficult since heat transfer must occur

from the rapidly moving air through the compressor casing to the cooling water, or from fins. This is an

ineffective process, and multistage compressors with interstage cooling are often a desirable alternative.

With a single stage and with a high P2 the outlet temperature T2 would be too high even if n could be

reduced to, say, 1.3.

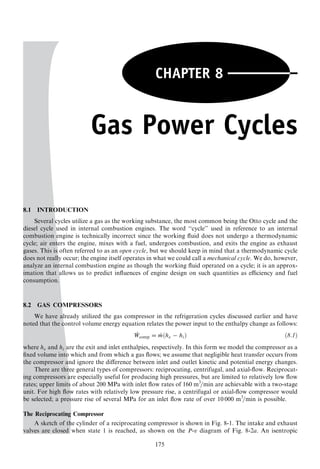

Consider a two-stage compressor with a single intercooler, as shown in Fig. 8-4a. The compression

processes are assumed to be isentropic and are shown in the T-s and P-v diagrams of Fig. 8-4b.

Referring to (8.5), the work is written as

wcomp = CpT1

P2

P1

ðk−1Þ=k

− 1

#

+ CpT3

P4

P3

ðk−1Þ=k

− 1

#

= CpT1

P2

P1

ðk−1Þ=k

+

P4

P2

ðk−1Þ=k

− 2

#

where we have used P2 = P3 and T1 = T3, for an ideal intercooler. To determine the intercooler pressure

P2 that minimizes the work, we let @wcomp=@P2 = 0. This gives

P2 = ðP1P4Þ1=2

or

P2

P1

=

P4

P3

ð8:8Þ

CHAP. 8] GAS POWER CYCLES 177

Fig. 8-3 Removal of heat during compression.

ð8:7Þ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-16-320.jpg)

![blades require extreme precision in manufacturing and installation to yield the maximum possible

pressure rise while avoiding flow separation. The area through which the air passes decreases slightly

as the pressure rises due to the increased density in the higher-pressure air. In fluid mechanics the

velocity and pressure at each stage can be analyzed; in thermodynamics we are concerned only with

inlet and outlet conditions.

CHAP. 8] GAS POWER CYCLES 179

Fig. 8-5 A centrifugal compressor.

Fig. 8-6 An axial-flow compressor.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-18-320.jpg)

![The combustion process is replaced by a heat transfer process with energy transferred from an

external source. It may be a constant-volume process or a constant-pressure process, or a

combination.

The exhaust process, used to restore the air to its original state, is replaced with heat transfer to

the surroundings.

All processes are assumed to be in quasiequilibrium.

The air is assumed to be an ideal gas with constant specific heats.

A number of the engines we will consider make use of a closed system with a piston-cylinder

arrangement, as shown in Fig. 8-7. The cycle shown on the P-v and T-s diagrams in the figure is

representative only. The diameter of the piston is called the bore, and the distance the piston travels

in one direction is the stroke. When the piston is at top dead center (TDC), the volume occupied by the

air in the cylinder is at a minimum; this volume is the clearance volume. When the piston moves to

bottom dead center (BDC), the air occupies the maximum volume. The difference between the maximum

volume and the clearance volume is the displacement volume. The clearance volume is often implicitly

presented as the percent clearance c, the ratio of the clearance volume to the displacement volume. The

compression ratio r is defined to be the ratio of the volume occupied by the air at BDC to the volume

occupied by the air at TDC, that is, referring to Fig. 8-7,

r =

V1

V2

ð8:11Þ

The mean effective pressure (MEP) is another quantity that is often used when rating piston-cylinder

engines; it is the pressure that, if acting on the piston during the power stroke, would produce an amount

of work equal to that actually done during the entire cycle. Thus,

Wcycle = ðMEPÞðVBDC − VTDCÞ ð8:12Þ

In Fig. 8-7 this means that the enclosed area of the actual cycle is equal to the area under the MEP

dotted line.

CHAP. 8] GAS POWER CYCLES 181

Fig. 8-7 A piston-cylinder engine.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-20-320.jpg)

![is the power stroke as the air (simulating the combustion products) expands isentropically to state 4. In

the final process heat transfer to the surroundings occurs and the cycle is completed. The spark-ignition

engine is modeled with this Otto cycle.

The thermal efficiency of the Otto cycle is found from

=

_Wnet

_Qin

=

_Qin − _Qout

_Qin

= 1 −

_Qout

_Qin

ð8:14Þ

Noting that the two heat transfer processes occur during constant-volume processes, for which the work

is zero, there results

_Qin = _mCvðT3 − T2Þ _Qout = _mCvðT4 − T1Þ ð8:15Þ

where we have assumed each quantity to be positive. Then

= 1 −

T4 − T1

T3 − T2

ð8:16Þ

This can be written as

= 1 −

T1

T2

T4=T1 − 1

T3=T2 − 1

ð8:17Þ

For the isentropic processes we have

T2

T1

=

V1

V2

k−1

and

T3

T4

=

V4

V3

k−1

ð8:18Þ

But, using V1 = V4 and V3 = V2, we see that

T2

T1

=

T3

T4

ð8:19Þ

Thus, (8.17) gives the thermal efficiency as

= 1 −

T1

T2

= 1 −

V2

V1

k−1

= 1 −

1

rk−1

ð8:20Þ

CHAP. 8] GAS POWER CYCLES 183

Fig. 8-8 The Otto cycle.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pottermerleccapitulo8-181128201225/85/Potter-merle-c-capitulo-8-22-320.jpg)