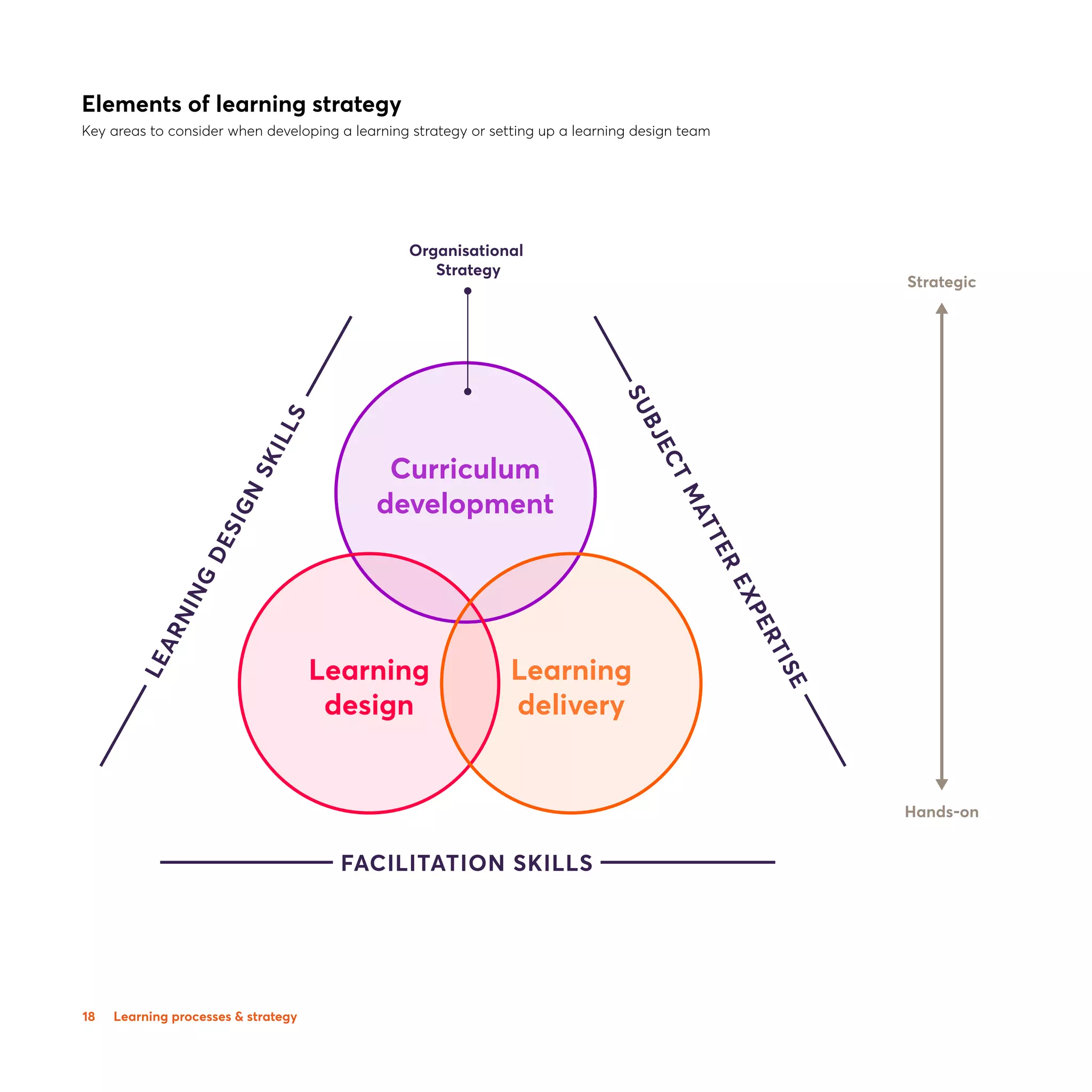

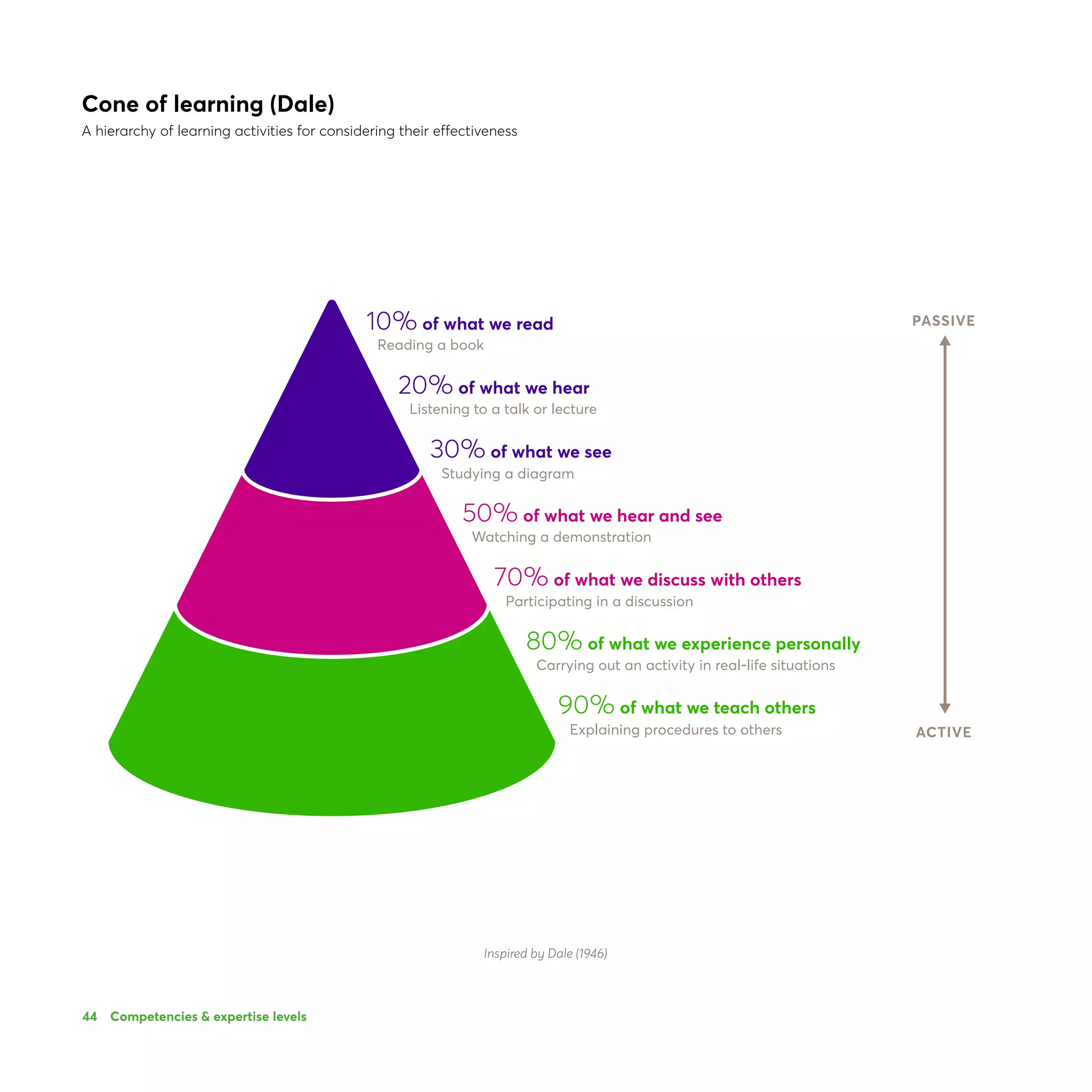

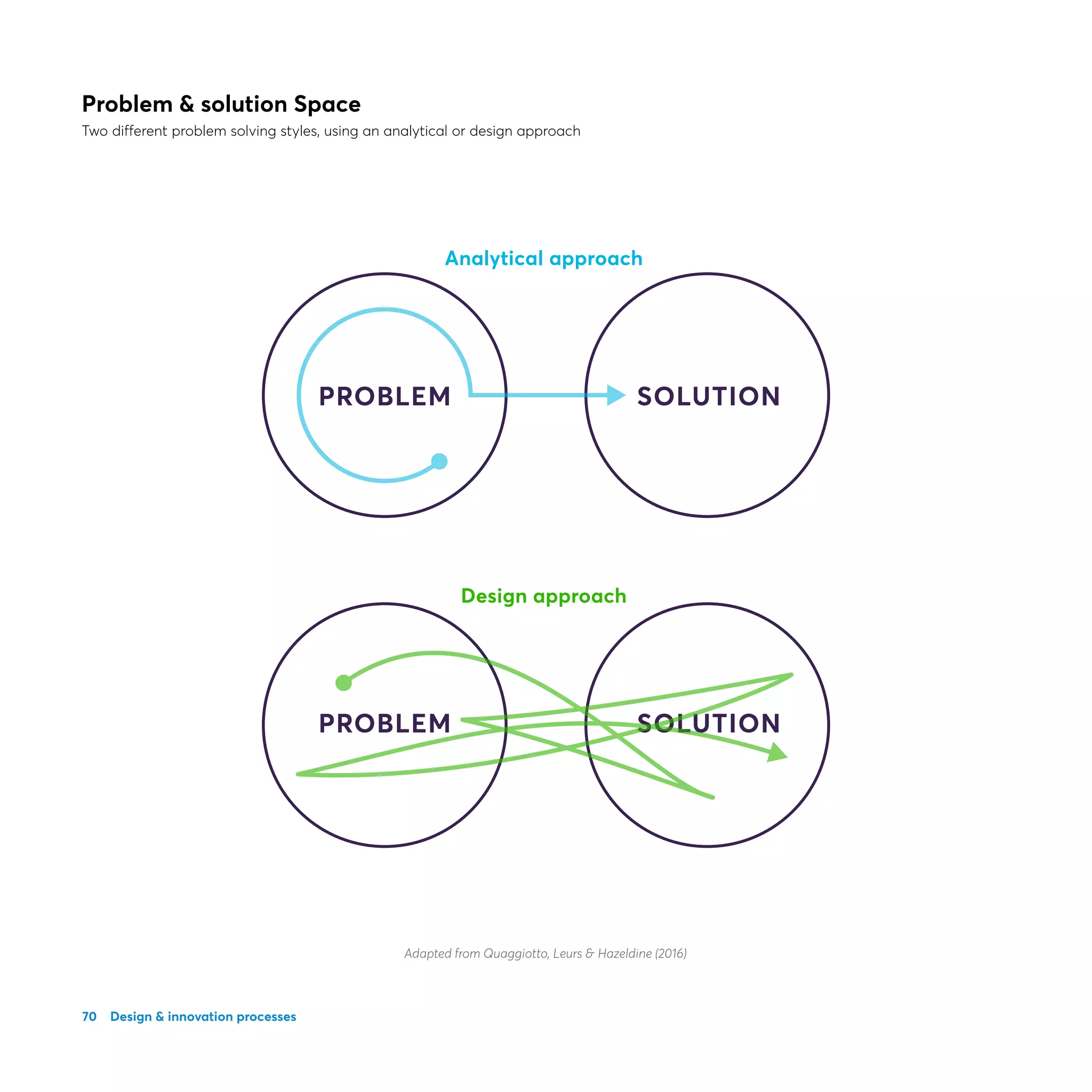

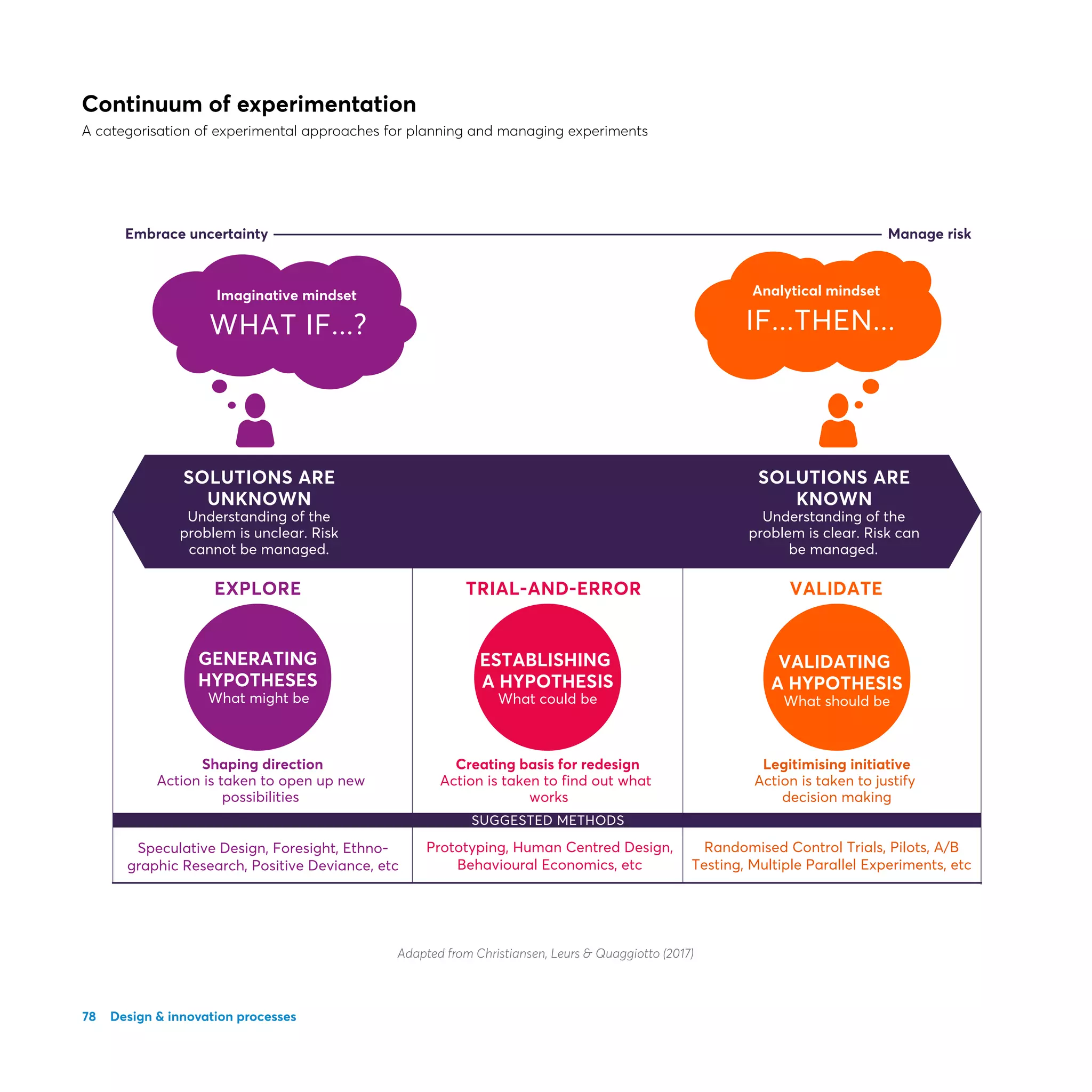

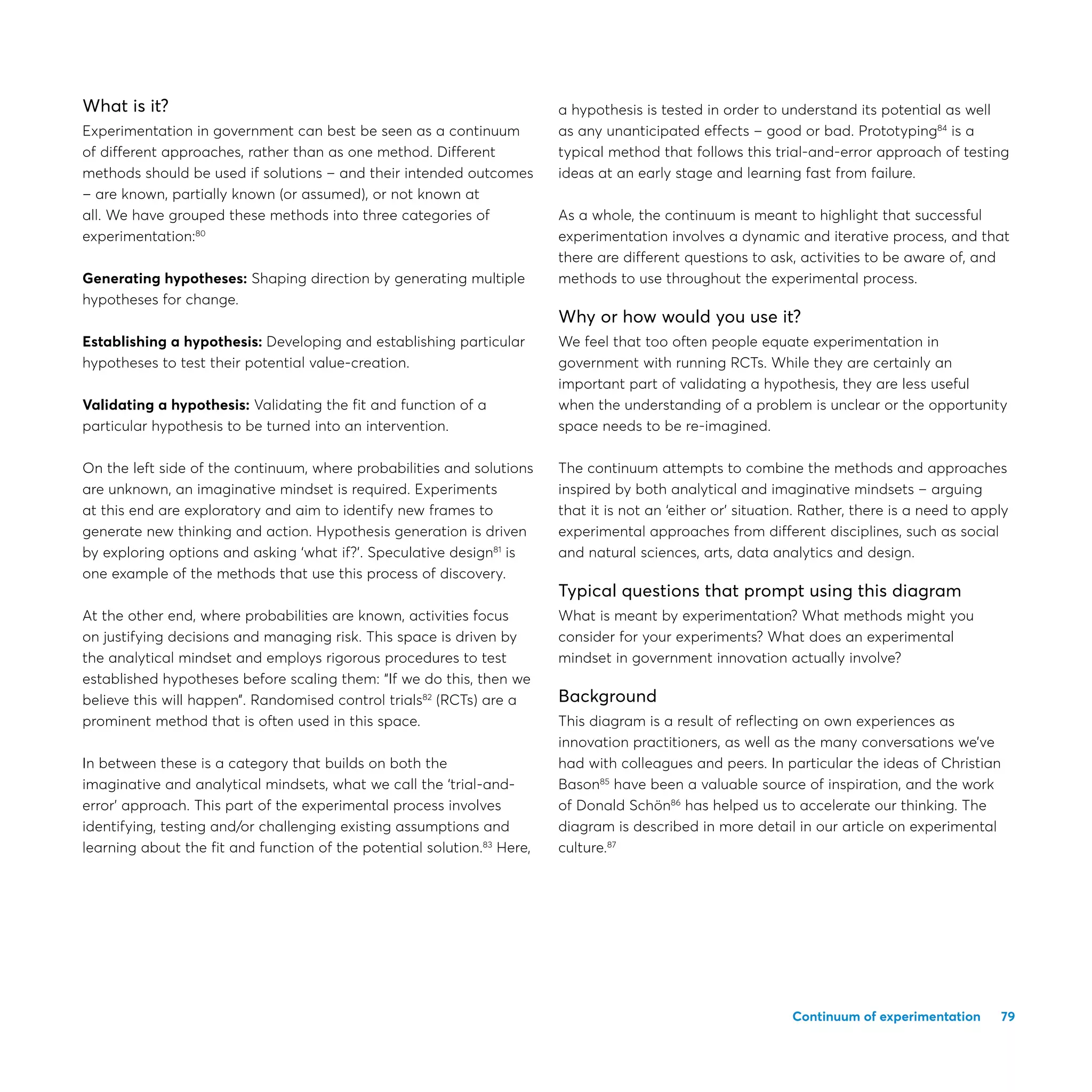

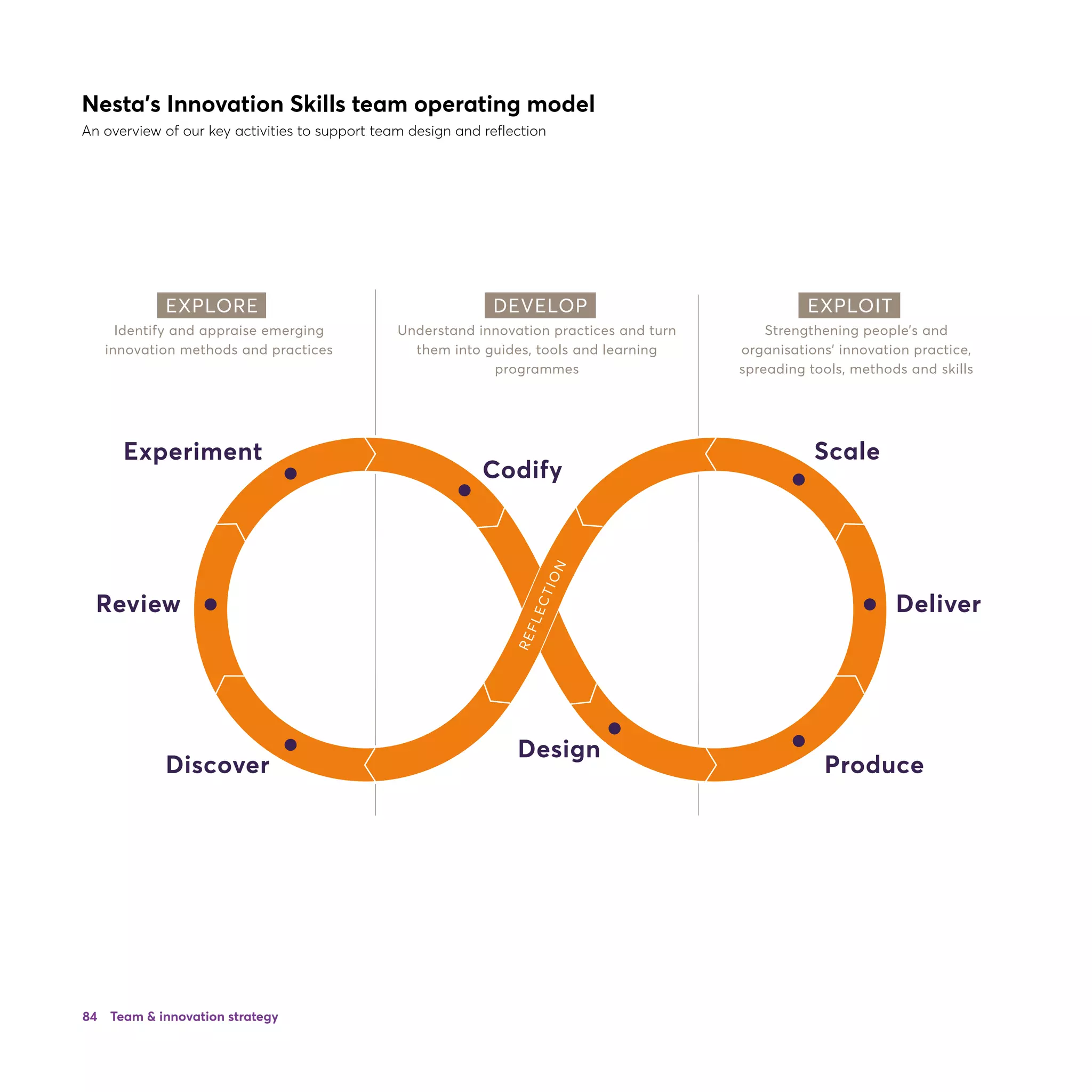

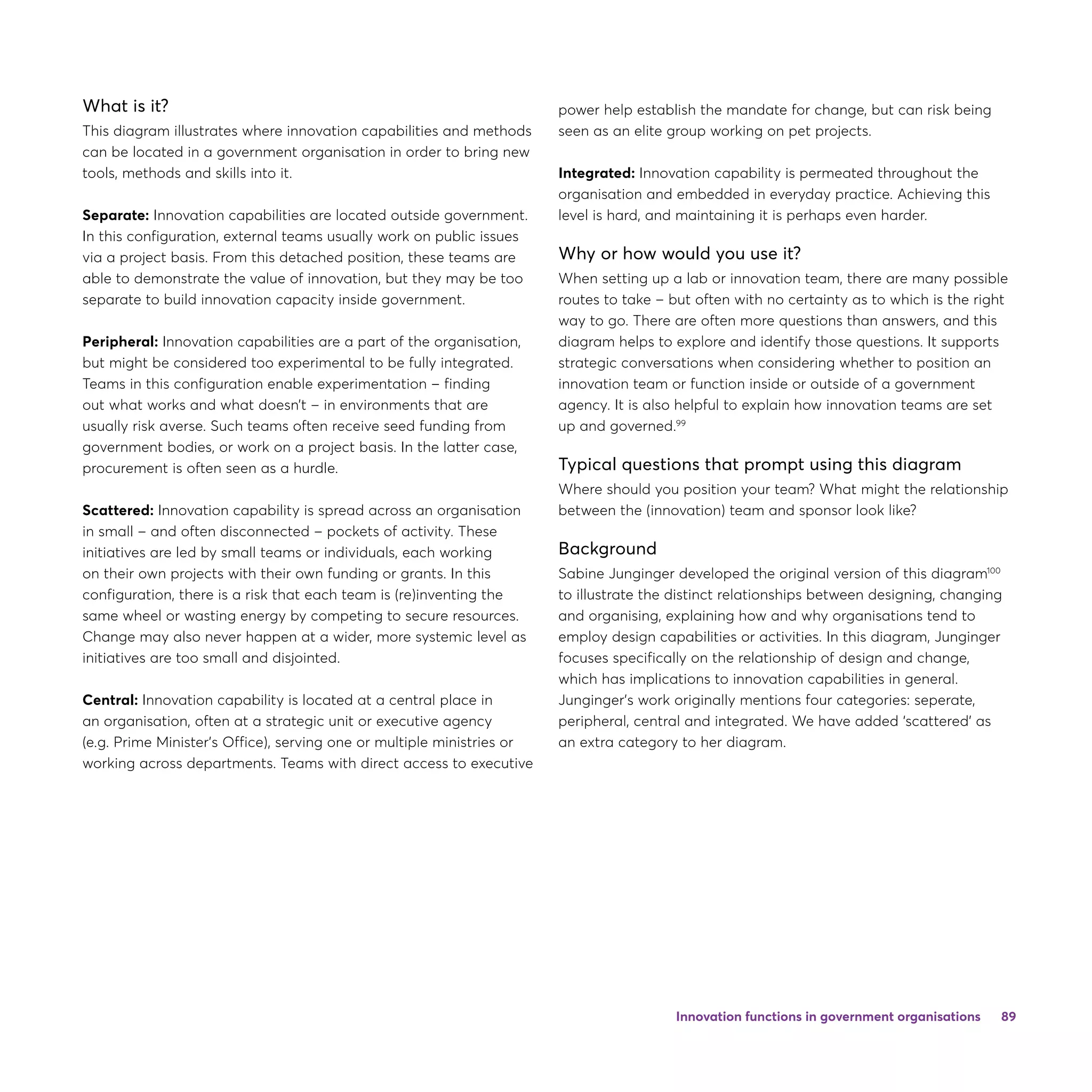

The document is a playbook for innovation learning authored by Bas Leur and Isobel Roberts, produced by Nesta’s innovation skills team. It comprises 35 diagrams designed to facilitate discussions on learning for innovation, targeting practitioners looking to enhance their innovation skills and strategies. The playbook categorizes diagrams into five areas to support the design and delivery of effective learning experiences and foster a deeper understanding of innovation processes.