Pic Projects And Applications Using C A Projectbased Approach 3rd Ed David W Smith Auth

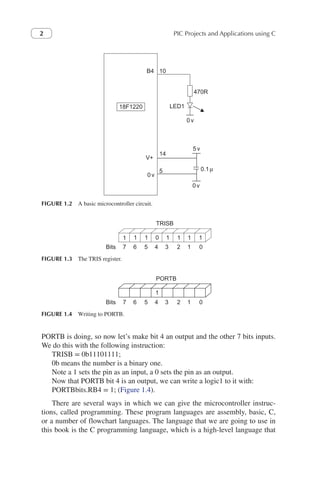

Pic Projects And Applications Using C A Projectbased Approach 3rd Ed David W Smith Auth

Pic Projects And Applications Using C A Projectbased Approach 3rd Ed David W Smith Auth