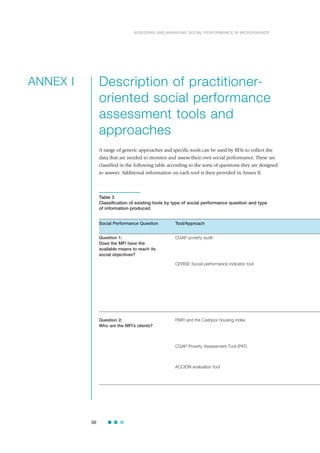

This document provides guidance on assessing and managing social performance in microfinance. It discusses conceptualizing social performance as going beyond just impact to also consider how an organization achieves its social goals. It recommends developing social performance management systems to monitor progress at different levels, from intent and design to outputs, outcomes and impacts. The document outlines tools and methods for assessment and provides examples of good practice from microfinance organizations that have implemented social performance management. It concludes with recommendations for how IFAD can support rural finance institutions in strengthening their social performance management capacity.