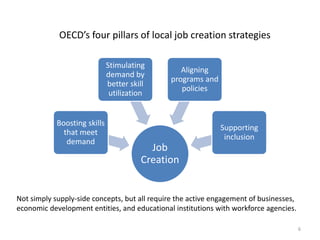

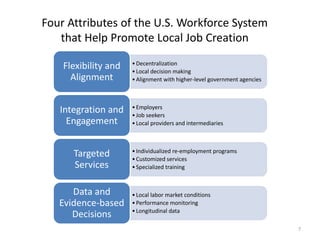

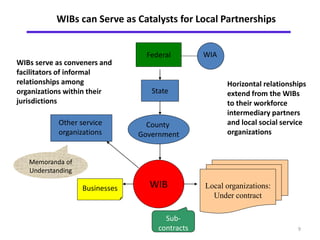

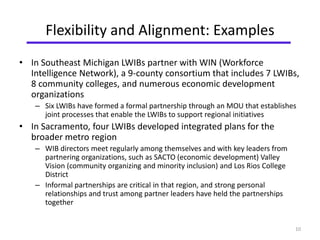

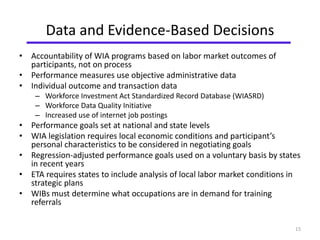

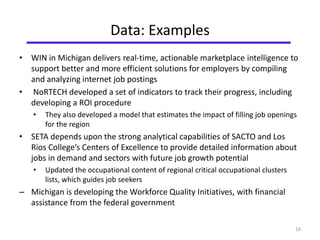

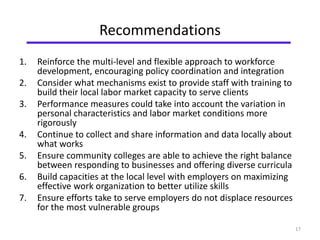

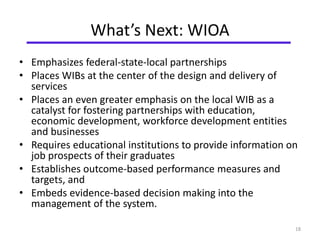

The document summarizes key aspects of local job creation strategies discussed at a 2014 OECD workshop. It describes how some Workforce Investment Boards (WIBs) in the US have leveraged the flexibility under the Workforce Investment Act to better align workforce programs with economic development, integrate services across organizations, target services to specific groups, and make data-driven decisions. Examples are provided of WIB partnerships in California and Michigan that have boosted skills training, business services, and coordination across education and economic development organizations to stimulate local job growth.