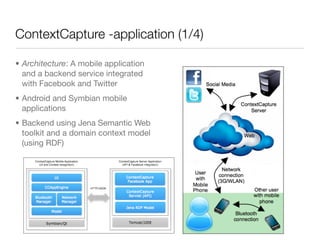

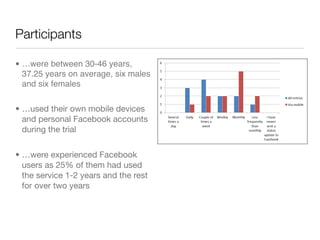

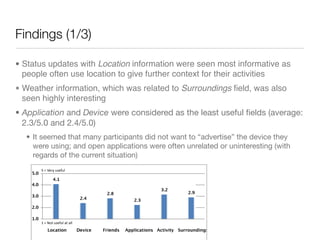

The document discusses a study on the privacy implications of using context-based awareness cues in social networks, focusing on a mobile application developed to allow users to share context information while maintaining privacy. It presents findings from user trials that indicate participants prefer abstract labels over precise location data to enhance privacy and control over shared information. The research suggests that context information adds value to communication but requires user-defined controls for effective privacy management.

![Challenges (privacy implications of context-

awareness in social networks)

Context (“anything that can Privacy

characterize the situation of an

entity”) • The level of information disclosure

can be difficult to manage

• The notion of ‘context’ can not be (awareness of consequences might

objectively defined (a prior) by not be clear)

settings, actions and actors

• People can end-up disclosing more

• Rather, context is the meaning that information than they meant to

the actions and actors acquire at (unwillingly)

any given time from the subjective

perspective [Mancini et al., 2009] • “Privacy is a dynamic and

continuously negotiated

• Awareness of ‘consequences’ is process” [Palen & Dourish, 2003]

important for grasping the effect of

actions determining the level of • People tend to appropriate the

information disclosure usage of a service to their own

needs [Barkhuus et al, 2008]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/percol2012privacy-of-awareness-cues-120321024922-phpapp01/85/PerCol-2012-Presentation-5-320.jpg)

![Context-based awareness cues

• Sharing context information can create awareness about the user’s situation

and thus enhance or make communication more efficient [Oulasvirta, 2008]

• Creating awareness can have multiple purposes...

• “Declaring one’s position is perhaps as much about deixis (pointing at and

referencing features of the environment) as it is about telling someone exactly

where you are” [Benford et al., 2004]

• Our hypothesis is that in many cases, rather than using exact parameters

provided by sensors, people would like to add semantic meaning by using

more abstract terms

• Also we claim that people prefer abstraction to ensure a certain level of

privacy

• The challenge is to give means for the dynamic abstraction while keeping as

brief as possible (cf. interactions in “4-second bursts”)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/percol2012privacy-of-awareness-cues-120321024922-phpapp01/85/PerCol-2012-Presentation-6-320.jpg)

![(Example)

• Creating a message:

“[User-defined message]

Sent from [Location] while [Activity] [Description] [Topic] and

[Applications Activity] with [Friends].”

As an example, a status update message generated with the previous rule

could be:

“I think this is the killer app for Pervasive Computing!

Sent from Conference Room 1 at PerCom 2012, Lugano, Switzerland while

listening to an interesting presentation by Dr. Firstname Lastname and using

Notepad with 4 conference buddies nearby.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/percol2012privacy-of-awareness-cues-120321024922-phpapp01/85/PerCol-2012-Presentation-11-320.jpg)

![Discussion

• Through the analysis of contextual information derived from mobile device

usage patterns it is possible to infer a lot of potentially privacy-sensitive

information

• There has been research in extracting these patterns from large datasets [Eagle

& Pentland, 2006; Farrahi & Gatica-Perez, 2008 and 2010]

• In addition there has been an increasing interest of exploring the social-side of

context-awareness in pervasive computing [Endler et al., 2011, Hosio et al.,

2010]

• We argue that the increased context-awareness is an inevitable step in

pervasive computing but the privacy implications of this progress are largely

not tested in the “real-world” yet

• Novel approaches for capturing and storing context “labels” are called for..](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/percol2012privacy-of-awareness-cues-120321024922-phpapp01/85/PerCol-2012-Presentation-20-320.jpg)