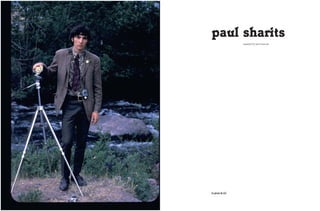

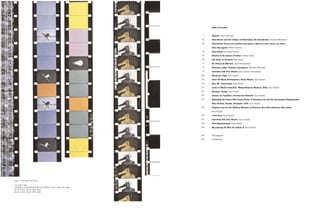

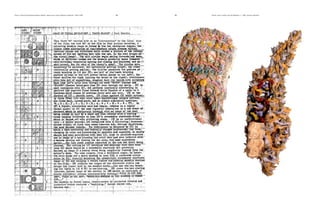

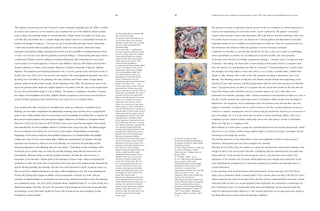

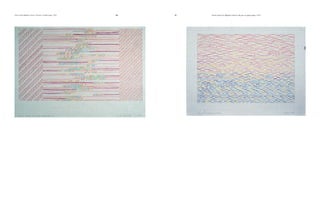

This document provides an overview of experimental filmmaker Paul Sharits and his body of work. It discusses his transition from painting to filmmaking in the 1960s and his pioneering work with flicker films and installations that questioned illusionism in cinema. Sharits developed unique notation systems using graph paper to conceptualize his films. His works like Ray Gun Virus and Razor Blades explored the material elements of film and challenged conventions of visual perception through stroboscopic color and flicker effects. The document examines how Sharits' films and installations create non-narrative experiences that analyze the viewing experience itself.