This document provides an overview of pediatrics as a medical specialty. It discusses pediatrics as the branch of medicine dealing with the care of children and adolescents. Key points include:

- Pediatrics covers children and adolescents under age 18 and aims to enable their healthy growth, development and achievement.

- India has a large child population but also high child mortality, with over 1.7 million under-5 deaths annually.

- Pediatrics encompasses care from premature neonates to adolescents and includes many specialized fields like neonatology and pediatric critical care.

- The historical development and current challenges of pediatrics in India are outlined.

![Introduction to Pediatrics -

Future of Child Health

The nation is addressing child health challenges with

greaterdynamism than ever before. Investments are being

madeforhealthprograms and healthsystem strengthening.

Conditional cash transfers and entitlements are enshrined

to stimulate demand for maternal, newborn and child

health care. ICDS is being strengthened, particularly in high

burden districts to addresschildhood undernutrition. The

country is surging ahead with stronger economy and

accelerated development. India ispoisedtoattainlow child

mortality rate, and improve remarkably the health and

nutrition status of her children in near future.

Table 1.4: Summary of maternal, newborn and child health services in the RMNCH+A Strategy under NRHM

Pregnancy, childbirth and Interventions

immediate newborn care

Skilled obstetric care and essential Package

newborn care including resuscitation Facility deliveries by skilled birth attendants

Neonatal resuscitation

Emergency obstetric and

newborn care (EmONC)

Postpartum care for mother and baby

Newborn and child care

Home-based newborn care

Facility-based newborn care

Essentialnewborn care (warmth, hygienic care, breastfeeding, extra care of small babies,

problem detection)

Linkages to facility-based newborn care for sick neonates

Program drivers: The schemes that drive uptake of the intervention packages

Janani Suraksha Yojana (]SY) that provides cash incentive to the woman (and to the

ASHA) for delivery in the facility

Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) that entitles the mother and less than one

month neonate to free delivery, medicines/blood, diet, pickup and drop in government

facilities

Navjat Shishu Suraksha Kan;akram that aims to train nurses and doctors in neonatal

resuscitation

Interventions

Home visits by ASHAs (six for facility born babies, on days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 42; an

extra visit on day 1 for home births)

Interventions for infants

Examination; counsel for warmth; breastfeeding; hygiene; extra care of low birthweight

babies; detection of sickness, referral

Interventions for mother

Postpartum care and counseling for family planning

ASHA given cash incentive for home care, birthweight record, birth registration and

immunization (BCG, first dose OPV and DPT)

Special newborn care units (SNCU)

These specialized newborn units at district hospitals with specialized equipments

including radiant warmers. These units have a minimum of 12-16 beds with a staff of

3 physicians, 10 nurses and 4 support staff to provide round the clock services for new

born requiring special care, such as those with very low birthweight, neonatal sepsis/

pneumonia and common complications

Newborn stabilization units (NBSU)

These are step down units providing facilities for neonates from the periphery where

babies can be stabilized through effective care. These are set up in CHCs and provide

services, including resuscitation, provision of warmth, initiation of breastfeeding,

prevention of infection and cord care, supportive care: oxygen, IV fluids, provision for

monitoring of vital signs and referral

Newborn care comers (NBCC)

These are special corners within the labor room at all facilities (PHC, CHC, DH) where

deliveries occur. Services include resuscitation, provision of warmth, prevention of

infections and early initiation of breastfeeding

Program drivers: The schemes that drive uptake of the intervention packages

Janani Shishu Suraksha Kan;akram (JSSK) that entitles the mother and neonate to free

delivery, medicines/blood, diet, pickup and drop in government facilities

Contd...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-10-320.jpg)

![acceleratedlymphoidgrowthis thefrequentfindingoflarge

tonsils and palpable lymph nodes in normal children

between 4 and 8 yr.

Growth of body fat and muscle mass. Body tissues can be

divided into fat and fat-free components. The lean body

mass includes muscle tissue, internal organs and skeleton

and contains only a small amount of fat. The growth in

leanbody massis primarilyduetoincrease in muscle mass.

Lean body mass correlates closely with stature. Taller

childrenhavegreaterleanbodymass thanshorter children

of the same age. After thepubertal growth spurt, boyshave

greater lean body mass compared to girls. Body fat is the

storehouse of energy. It is primarily deposited in the sub

cutaneous adipose tissue. Girls have more subcutaneous

adipose tissue than boys. Moreover, the sites and quantity

of adipose tissue differs in girls and boys. Girls tend to add

adiposetissue to breasts, buttocks, thighs and back of arms

during adolescence.

SOMATIC GROWTH

Skeletal Growth

Skeletal growth is a continuous process occurring during

the whole of childhood and adolescence. It is steady until

the pubertal growth spurt when it accelerates and

subsequently slows considerably. The skeleton is mature

oncetheepiphysis orgrowthplates at theend oflongbones

fuse to the shaft or diaphysis. This occurs by about 18 yr in

girls and 20-22 yr in boys.The degree of skeletal maturation

closely correlates with the degree of sexual maturation. A

child who has advanced sexual maturity will also have

earlier skeletal maturation.

Skeletalmaturationisassessedby notingthe appearance

and fusion of epiphysis at the ends of long bones. Apart

from this, bone mineraldensity can beascertainedby dual

energy X-ray absorptiometry [DXA]. This method allows

assessment of bonemineralcontentanddensityat different

ages.

Normal Growth and its Disorders

-

Bone Age Estimation

Assessment of bone agepostnatally is based on (i) number,

shape and size of epiphyseal centers and (ii) size, shape

and density of the ends of bones. Tanner and Whitehouse

described 8 to 9 stages of development of ossification

centers and gave them 'maturity scoring'.Fifty percent of

the score was given for carpal bones, 20% for radius, ulna

and 30% for phalanges. Twenty ossification centers are

generallyusedfor determining theboneage.Theseinclude:

(i) carpal bones, (ii) metacarpals, (iii) patella, (iv) distal and

proximal toes in both sexes; and (v) distal and middle

phalanges in boys and distal and proximal phalanges in

girls.Todeterminetheskeletalage ininfantsbetween3 and

9months, aradiographofshoulderismost helpful. Asingle

film of hands and wrists is adequate in children between

the ages of 1 and 13 yr. For children between 12 and 14 yr,

radiographs of elbow and hip give helpful clues.

Eruption of Teeth

Primary teeth. The teeth in the upper jaw erupt earlier than

those in the lower jaw, except for lower central incisors

and second molar (Table 2.2).

Permanent teeth. Theorder oferuptionis shown inTable 2.2.

The first molars are the first to erupt.

ASSESSMENT OF PHYSICAL GROWTH

Weight. The weight of the child in the nude or minimal

light clothing is recordedaccuratelyon a lever or electronic

type of weighing scale (Fig. 2.4). Spring balances are less

accurate. The weighing scale should have a minimum unit

of 100 g. It is important that child beplacedinthe middle of

weighing pan. The weighing scale should be corrected for

any zero error before measurement. Serial measurement

should be done on the same weighing scale.

Length. Length is recorded for children under 2 yr of age.

Hairpins are removed and braids undone. Bulky diapers

should be removed. The child is placed supine on a rigid

Table 2.2: Timing of dentition

Primary dentition Time of eruption, months Time of fall, years

Upper Lower Upper Lower

Central incisors 8-12 6-10 6-7 6-7

Lateral incisors 9-13 10-16 7-8 7-8

First molar 13-19 14-18 9-11 9-11

Canine 16-22 17-23 10-12 9-12

Second molar 25-33 23-31 10-12 10-12

Permanent teeth Time of eruption, years

Upper Lower Upper Lower

First molar 6-7 6-7 First premolar 10-11 10-12

Central incisors 7-8 6-7 Second premolar 10-12 10-12

Lateral incisors 8-9 7-8 Second molar 12-13 11-13

Canine 11-12 10-12 Third molar 17-21 17-21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-16-320.jpg)

![__E

_

s

_

s

_

e

_

n

_

t

_

ia

_

l

_

P

_

e

_

d

_

i

_

a

_

tr

_

ic

_

s_________________________________

Table 5.5: Causes of hyponatremia

Hypovolemic hypona

tremia (sodium loss

in excess of free water)

Normovolemic hypo

natremia (conditions

that predispose to

SIADH)

Hypervolemic hypo

natremia (excess free

water retention)

Renal loss: Diuretic use,

osmotic diuresis, renal salt

wasting, adrenal insufficiency,

pseudohypoaldosteronism

Extra-renal loss: Diarrhea,

vomiting, drains, fistula

sweat (cystic fibrosis),

cerebral salt wasting

syndrome, third-spacing

(effusions, ascites)

Inflammatory central nervous

system disease (meningitis,

encephalitis), tumors

Pulmonary diseases (severe

asthma, pneumonia)

Drugs (cyclophosphamide,

vincristine)

Nausea, postoperative

Congestive heart failure,

cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome,

acute or chronic renal failure

urine output and high urine sodium. The treatments are

different, as cerebral salt wasting requires replacement of

urinary salt-water losses while SIADHismanagedby fluid

restriction.

Hyperosmolality resulting from non-sodium molecules

(hyperglycemia, mannitol overdose) draws water from the

intracellular space to dilute the extracellular sodium

concentration. Factitious hyponatremia, reported when

hyperlipidemia (chylomicronemia) or hyperproteinemia

coexist, isuncommondue to use ofion-selectiveelectrodes.

Patients are generally symptomatic when serum sodium

concentrationfalls below 125 mEq/1 or the decline is acute

(<24 hr). Early features include headache, nausea,

vomiting, lethargy and confusion. Advanced mani

festations are seizures, coma, decorticate posturing, dilated

pupils, anisocoria, papilledema, cardiac arrhythmias,

myocardial ischemia and central diabetes insipidus.

Cerebral edema occurs at levels of 125 mEq/1 or less.

Hypo-osmolality causes influx of water into the

intracellular space, which results in cytotoxic cerebral

edema and increased intracranial pressure and can lead

to brain ischemia, herniation and death. The brain's

primary mechanism in adapting to hyponatremia is the

extrusion of intracellular electrolytes and organic

osmolytes. Some ofthese organic osmolytes are excitatory

amino acids, such as glutamate and aspartate that can

produce seizures in the absence of detectable cerebral

edema. Major risk factors for developing hyponatremic

encephalopathyareyoungage,hypoxemiaandneurological

disease. Children are at significantly higher risk than are

adults for developing hyponatremic encephalopathy due

to their relatively larger brain to intracranial volume ratio

compared with adults. Hyponatremia in association with

increased intravascular volume can result in pulmonary

edema, hypertension and heart failure. Asymptomatic

hyponatremia inpretermneonatesisassociatedwith poor

growth and development, sensorineural hearing loss and

a risk factor for mortality in neonates who suffered

perinatal birth asphyxia.

Treatment

The first step is to determine whether hyponatremia is

acute (<48 hr) or chronic (>48 hr), symptomatic or

asymptomatic and evaluate the volume status (hyper

volemic, euvolemic, hypovolemic) (Box 5.1). The under

lying cause should be corrected, where possible. Losses

due to renal or adrenocortical disease are suggested by

urinary sodium concentration of more than 20 mEq/1 in

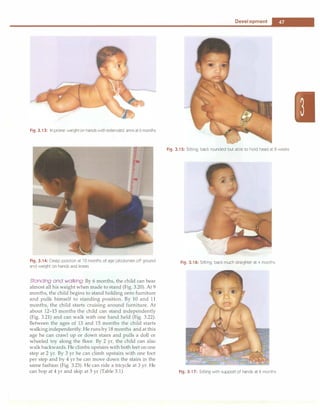

presence of clinically evident volume depletion (Fig. 5.5).

In case of hypovolemic hyponatremia the fluid and

sodium deficit is estimated and replaced over 24 to 48 hr.

The dose of sodium required is calculated using the

formula:

Sodium deficit (mEq) =

0.6 x body wt (kg) x [(desired Na+

) - (observed Na+

)] mEq/1

The optimal rate of correction is 0.6 to 1 mEq/1/hr until

the sodium concentration is 125 mEq/1 and then at a

Box 5.1: Treatment of hyponatremia

• Treat hypotensionfirst, regardless of serum sodium (normal

saline bolus, Ringer lactate, 5% albumin). WHO oral

rehydration solution is preferable for asymptomatic cases

with hypovolemia

• Correct deficit over 48 to 72 hr for chronic hyponatremia.

Rapid decline is associated with risk of central pontine

myelinosis. Recommended rate of increase is 0.5 mEq/

!/hr (8-10 mEq/1/day). Correction in the first 48 hr should

not exceed 15-20 mEq/1

• Acute and symptomatic hyponatremia may be corrected

rapidly. For symptomatic cases, immediate increase in

serum sodium level by 5-6 mEq/1 with hypertonic saline

(3% saline) is recommended. IV infusion at a dose of 3-5

ml/kg over 1-2 hr will raise serum sodium by 5-6 mEq/1.

Alternatively, 3% saline may be given as 1-3 boluses at 2

ml/kg/bolus over 10 min (maximum 100 ml/bolus)

• Stop further therapy with 3% saline when patient is either

symptom free and/or acute rise in sodium of 10 mEq/1 is

noted in first 5 hr.

• Increase of serum Na+

can be estimated using Adrogue

Madias formula (Box 5.2)

• Hypotonic infusates (0.45% dextrose normal saline) are used

as maintenancefluid. Normal saline should be avoided except

for correction of hypovolemia; can aggravate cerebral edema

in those with impaired free water clearance.

• Fluid restriction alone is needed for SIADH; sodium and

water restriction is required in hypervolemic hyponatremia.

Diuretics may be added in refractory cases.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-60-320.jpg)

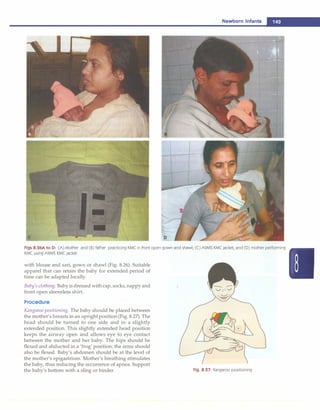

![Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances

-

Assessment of volume status

=i

Hypovolemia

Total body water .J,

Total body sodium U

J -

Euvolemia

l

Total body water i

Total body sodium H

Hypervolemia

Total body water ii

Total body sodium i

• + • J

U [Na•] >20

r- !

U [Na] <20 U [Na•] >20 U [Na•] >20

.--t-

u [Na] <20

• • f • -.

Extrarenal SIADH Acute, chronic Nephrotic syndrome

Renal losses

Diuretics

Mineralocorticoid deficiency

Salt losing nephropathy

Cerebral salt wasting

losses

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Third spacing

Glucocorticoid deficiency

Hypothyroidism

renal failure Cirrhosis

Congestive heart failure

Stress

Drugs

Renal tubular acidosis

Fig. 5.5: Diagnostic approach to hyponatremia. U(Na•) urinary sodium, mEq/1; i increased; !decreased

slower rate. For symptomatic patients a combination of

intravenous infusion of hypertonic saline (3% sodium

chloride) and fluid restriction rapidly increase serum

sodium by 5-6 mEq/1 and ameliorates the symptoms.

Thereafter, if the symptoms remit, the remaining deficit

can be corrected slowly over the next 1 to 3 days. When

slow correction of hyponatremia in a volume-expanded

patient is indicated, water restriction alone, or if this is

unsuccessful, in combination with a loop-diuretic such as

furosemide is preferred. Serum sodium concentration

should be monitored every 2 to 4 hr and appropriate

adjustments made.

Aggressive therapy with hypertonic saline in patients

with chronic hyponatremia (where brain adaptation to

hypo-osmolality has set in by extrusion of intracellular

electrolytes and organic osmoles) can lead to osmotic

demyelination called central pontine myelinolysis. This

condition, which isoften irreversibleisreportedinpatients

with liver disease, severe malnutrition and hypoxia.

Patients generally become symptomatic 2 to 7 days

followingrapidcorrection (>25mEq/1inthefirst24-48 hr)

of chronic hyponatremia. Clinical features include

mutism, dysarthria, spastic quadriplegia, ataxia, pseudo

bulbar palsy, altered mental status, seizures and

hypotension.

Fluid restriction alone has no role in the management

of symptomatic hyponatremia. Normal saline is also

inappropriate for treating hyponatremic encephalopathy

due to non-hemodynamic states of vasopressin excess,

such as SIADH and postoperative hyponatremia, as it is

not sufficiently hypertonic toinduce reduction in cerebral

edema. In presence of elevated ADH levels there is

impaired ability to excrete free water with the urine

osmolality exceeding that of plasma. V2-receptor anta

gonists or vaptans that block the binding of ADH to its

V2 receptor, are yet not recommended for treatment of

hyponatremic encephalopathy. These agents may have

a role in treating euvolemic hyponatremia from SIADH

and hypervolemic hyponatremia in congestive heart

failure.

Hypernatremia

Hypernatremia is defined as increase in serum sodium

concentration to levels more than 150 mEq/1. It may be

accompanied by the presence of low, normal or high total

body sodium content. The major cause of hypernatremia

is loss of body water, inadequate intake of water, a lack of

antidiuretic hormone (ADH), or excessive intake of

sodium (e.g. solutions with high sodium such as sodium

bicarbonate) (Table 5.6).Diabetesinsipidusmayresultfrom

a deficiency of ADH or its end organ unresponsiveness.

In the presence of an intact thirst mechanism, a slight

increase in serum sodium concentration (3 to 4 mEq/1)

above normal elicits intense thirst. The lack of thirst in

the presence of hypernatremia in a mentally alert child

indicates adefectin eithertheosmoreceptors orthe cortical

thirst center. The most objective sign of hypernatremia is

lethargy or mentalstatuschanges,whichproceedsto coma

and convulsions. With acute and severe hypernatremia,

the osmotic shift of water from neurons leads to shrinkage

of the brain and tearing of the meningeal vessels and

intracranialhemorrhage;slowlydevelopinghypematremia

Table 5.6: Causes of hypernatremia

Net water loss

Pure water loss

Insensible losses

Diabetes insipidus

Inadequate breastfeeding

Hypotonicfluid loss

Renal: Loop, osmotic diuretics,postobstructive,polyuric phase

of acute tubular necrosis

Gastrointestinal: Vomiting, nasogastric drainage, diarrhea;

lactulose

Hypertonic sodium gain

Excess sodium intake

Sodium bicarbonate, saline infusion

Hypertonic feeds, boiled skimmed milk

Ingestion of sodium chloride

Hypertonic dialysis

Endocrine: Primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing syndrome](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-61-320.jpg)

![__E_s_s_e_n_ti_a _i _P_e_d_ia_t_ri_cs--------------------------------

is generally well tolerated. The latter adaptation occurs

initially by movement of electrolytes into cells and later

by intracellular generation of organic osmolytes, which

counter plasma hyperosmolarity.

Treatment

Treatment involves restoring normal osmolality and

volume and removal of excess sodium through the

administration of diuretics and hypotonic crystalloid

solutions. The speed of correction depends on the rate of

development of hypernatrernia and associated symptoms

(Box 5.2). Because chronic hypernatrernia is well tolerated,

rapid correction offers no advantage and may be harmful

since it may result in brain edema. Usually a maximum of

10% of the serum sodium concentration or about 0.5 mEq/

1/hr should be the goal rate of correction. Seizures due to

hypernatremia are treated using 5-6 ml/kg infusion of

3% saline over 1-2 hr.

POTASSIUM

Physiology

------------------

Potassium being a predominantly intracellular cation, its

blood levels are unsatisfactory indicator of total body

stores. Normal serum concentration of potassium ranges

between 3.5 and 5 mEq/1. Common potassium-rich foods

include meats, beans, fruits and potatoes. Gastrointestinal

absorption is complete and potassium homeostasis is

Box 5.2: Treatment of hypernatrernia

• Treat hypotension first, regardless of serum sodium

(normal saline bolus, Ringer lactate, 5% albumin)

• Correct deficit over 48 to 72 hr. Rapid decline of chronic

(>48 hr) hypematremia is associated with risk of cerebral

edema. Recommended rate of drop in serum sodium is

0.5 mEq/1/hr (10-12 mEq/1/day)

• Oral solutions preferred to parenteral correction

• Generally hypotonic infusates are used (infusate sodium

of - 40 mEq/1, as N/4 or N/5 saline). Sodium free fluids

should be avoided (except in acute onset hypematremia,

e.g. sodium overload)

• Decline of serum Na+ can be estimated using Adrogue

Madias Formula:

D[Na

+

J= {[Na

+

Jinf

+ (K

+

Jinf- [Na

+L)

(TBW + 1)

Where �[Na+] expected change in serum sodium; [Na+]inf

sodium and [K+]infpotassium in 1 liter of the infusate, [Na+Js

serum sodium; TBW or total body water = 0.6 x body

weight

• Seizures due to hypematremia are treated using hypertonic

(3%) saline at 5-6 ml/kg infusion over 1-2 hr.

• Renal replacement therapy (peritoneal or hemodialysis,

hemofiltration) is indicated for significant hypematremia

(>180-200 mEq/1) with concurrent renal failure and/or

volume overload.

• Ensure correction of ongoing fluid losses; frequent bio

chemical and clinical reassessment is needed.

maintainedpredominantlythroughtheregulationof renal

excretion. The fractional excretion of potassium is about

10%,chieflyregulated byaldosteroneat thecollectingduct.

Renal adaptive mechanisms maintain potassium

homeostasis until theglomerularfiltration ratedropstoless

than 15-20 ml/min. Excretion is increased by aldosterone,

high sodium delivery to the collecting duct (e.g. diuretics),

urine flow (e.g. osmotic diuresis), blood potassium level,

glucocorticoids, ADH and delivery of negatively charged

ions to the collectingduct (e.g. bicarbonate). Inrenal failure,

the proportion of potassium excreted through the gut

increases, chiefly by the colon in exchange for luminal

sodium.

Aldosterone and insulin are two play important roles

inpotassiumhomeostasis. Insulin stimulatedbypotassium

ingestion increases uptake of potassium in muscle cells,

through increased activity of the sodium pump. High

potassium levels stimulate its renal secretion via aldos

terone-mediated enhancement of distal expression of

secretory potassium channels (ROMK). Insulin, beta

adrenergic stimuli and alkalosis enhance potassium entry

into cells. The reverse happens with glucagon, a-adrener

gic stimuli and acidosis.

Hypokalemia

Hypokalernia is defined as a serum potassium level below

3.5 mEq/1. The primary pathogenetic mechanisms result

ing in hypokalemia include increased losses, decreased

intake or transcellular shift (Table 5.7). Vomiting, a

Table 5.7: Causes of hypokalernia

Increased losses

Renal

Renal tubular acidosis (proximal or distal)

Drugs (loop and thiazide diuretics, amphotericin B,

aminoglycosides, corticosteroids)

Cystic fibrosis

Gitelman syndrome, Bartter syndrome, Liddle syndrome

Ureterosigmoidostomy

Mineralocorticoid excess (Cushing syndrome, hyperal

dosteronism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (11 P-hydroxy

lase, 17 o:-hydroxylase deficiency)

High renin conditions (renin secreting tumors, renal artery

stenosis)

Extrarenal

Diarrhea, vomiting, nasogastric suction, sweating

Potassium binding resins (sodium polystyrene sulfonate)

Decreased intake or stores

Malnutrition, anorexia nervosa

Potassium-poor parenteral nutrition

Intracellular shift

Alkalosis, high insulin state, medications (P2-adrenergic

agonists, theophylline, barium, hydroxychloroquine),

refeeding syndrome, hypokalemic periodic paralysis,

malignant hyperthermia, thyrotoxic periodic paralysis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-62-320.jpg)

![__E_s_s_ e_n_t_ia_l_P_e _d_ia_t_ri_c_

s __________________________________

calcium absorption in the distal convoluted tubule. These

mechanisms help to maintain normal levels of serum

calcium.

Plasma calcium exists in 3 different forms: 50% as

biologically active ionized form, 45% bound to plasma

proteins (mainlyalbumin)and5%complexedtophosphate

and citrate. In the absence of alkalosis or acidosis, the

proportion of albumin-bound calcium remains relatively

constant. Metabolic acidosis leads to increased ionized

calcium from reduced protein binding and alkalosis has

the opposite effect. Plasma calcium is tightly regulated

despite its large movements across the gut, bone, kidney

and cells in the normal range of 9-11 mg/dl.

Because calcium bindsto albumin and onlythe unbound

(free or ionized) calcium is biologically active, the serum

level must be adjusted for abnormal albumin levels. For

every1 g/dldropin serumalbuminbelow4 g/dl,measured

serum calcium decreases by 0.8 mg/dl. Corrected calcium

can be calculated using the following formula:

Corrected Ca =

[4 - plasma albumin in g/dl] x 0.8 + measured serum calcium

Alternatively, serum free (ionized) calcium levels can

be directly measured, negating the need for correction

for albumin.

Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is defined as serum calcium less than

8 mg/dl or ionized calcium below 4 mg/dl. The causes

and algorithm for investigating the etiology are shown in

Table 5.9 and Fig. 5.8. Hypocalcemia manifests as central

nervous system irritabilityandpoormuscular contractility.

Newborns present with nonspecific symptoms such as

lethargy, poor feeding, jitteriness, vomiting, abdominal

distension and seizures. Children may develop seizures,

twitching, cramps and rarely laryngospasm (Box 5.5).

Tetany and signs of nerve irritability may manifest as

musculartwitching, carpopedalspasmandstridor.Latent

tetany can be diagnosed clinically by clinical maneuvers

such as Chvostek sign (twitching of the orbicularis oculi

Table 5.9: Causes of hypocalcemia

Neonatal: Early (within 48-72 hr after birth) or late (3-7 days

after birth) neonatal hypocalcemia; prematurity; infant of

diabetic mother; neonates fed high phosphate milk

Parathyroid: Aplasia or hypoplasia of parathyroid glands,

DiGeorge syndrome, idiopathic; pseudohypoparathyroidism;

autoimmune parathyroiditis; activating mutations of calcium

sensing receptors

Vitamin D: Deficiency; resistance to vitamin D action; acquired

or inherited disorders of vitamin D metabolism

Others: Hypomagnesernia; hyperphosphatemia (excess intake,

renal failure); malabsorption syndromes; idiopathic

hypercalciuria; renal tubular acidosis; metabolic alkalosis;

hypoproteinemia; acute pancreatitis

Drugs: Prolonged therapy with frusernide, corticosteroid or

phenytoin

Low serum calcium

•

Correct for level of serum albumin;

measure ionized calcium

•

Normal

J_

Low

+

No action] Serum magnesium

+

High

•

Normal

Serum phosph�

=

LowJ

Correct hypomagnesemiaj

+

Low

.r

Parathormone l?5(0H)D3and 1,25(0H)2D3 levels

l

+L. --F •

+

Hi�

!

Renal failure

Pseudohypoparathyroidism

Tumor lysis

I

+

Low �OH)D3 low ll25(0H)D3 normal

I

1,25(0HhD3

r 1,25(0HhD3 low high

+ + +

Vitamin D

deficiency

VDDR type I

Renal failure

VDDR type II

Fig. 5.8: Algorithm for evaluation of hypocalcemia. VDDR vitamin D dependent rickets](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-66-320.jpg)

![for patients with severe hypermagnesemia and renal

impairment, or those with serious cardiovascular or

neuromuscular symptoms.

ACID-BASE DISORDERS

Regulation of Acid-Base Equilibrium

The body is sensitive to changes in blood pH level, as

disturbances in acid-base homeostasis can result in

denaturation of proteins and inactivation of enzymes that

may be potentially fatal. Strong mechanisms exist to

regulate acid-base balance and maintain arterial pH (7.35

to7.45), pC02 (35 to 45 mm Hg) and HC03-(20 to 28 mEq/1)

within a narrow range.

Acidemia is defined as H+

concentration exceeding

45 nmol/1 (pH <7.35); values below 35 nmol/1 (pH>7.45)

define alkalemia. The disorders that cause acidemia or

alkalemia are termed as acidosis and alkalosis respectively.

Metabolic activity results in production of two types of

acids, carbonic acid (a volatile acid, derived from carbon

dioxide) and nonvolatile acids (including sulfuric acid,

organic acids, uric acid and inorganic phosphates).

Accumulation of H+

ions of nonvolatile acidsdueto excess

production or inadequate buffering, failure to excrete H+

Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances -

or loss of bicarbonate results in metabolic acidosis. If the

reverse occurs, it results in metabolic alkalosis. The

principle mechanism for carbon dioxide handling is by

the lungs. Hyperventilation results its CO2 washout and

drop in arterial pC02 (respiratory alkalosis), hypo

ventilation has the opposite effect (respiratory acidosis).

When only oneprimaryacid-baseabnormality occurs and

its compensatory mechanisms are activated, the disorder

is classified as simple acid-base disorder. A simple

algorithmfordefining simpleacid-base disordersis shown

in Fig. 5.9. When a combination of disturbances occurs,

the disorder is classified as a mixed acid-base disorder.

The latter aresuspectedwhenthecompensationin a given

patient differs from the predicted values in Table 5.11.

In order to maintain body homeostasis, changes in pH

are resisted by a complex system of intracellular and

extracellular buffers. The first line of defense, are the

chemical buffers. In metabolic disorders the extracellular

buffersrapidlytitrate theaddition of strong acids or bases.

Intracellular buffers chiefly accomplish the buffering of

respiratory disorders. Secondary respiratory compen

sations to metabolic acid-base disorders occur within

minutes and is completed by 12 to 24 hr. In contrast

secondary metabolic compensation of respiratory

Blood pH

Acidemia

(l pH)

--,

t

�

Lr�

IRespiratory acidosis Metabolic acido� Respiratory alkalosis Metaboli��

Respiratory acidosis

with compensatory

metabolic alkalosis

Metabolic acidosis

with compensatory

respiratory alkalosis

Metabolic alkalosis

with compensatory

respiratory acidosis

Fig. 5.9; Algorithm for simple acid-base disorders

Table 5.11: Compensation for primary acid-base disorders

Disorder Primary event Compensation Expected Compensation

Metabolic acidosis l [HC03

-J l pC02 pC02 l by 1-1.5 mm Hg for 1 mEq/l l[HC03]

Metabolic alkalosis t [HC03

-J t pC02 pC02 t by 0.5-1 mm Hg for 1 mEq/1 t [HC03]

Respiratory acidosis

Acute (<24 hr) tpC02 t[HC03-J [HC03] t by 1 mEq/1 for 10 mm Hg t pC02

Chronic (3-5 days) tpC02 ft [HC03-J [HC03

-J t by 4 mEq/1 for 10 mm Hg t pC02

Respiratory alkalosis

Acute (<24 hr) lpC02 l[HC03

-J [HC03

-J l by 1-3 mEq/1 for 10 mm Hg l pC02

Chronic (3-5 days) lpC02 U[HC03

-J [HC03

-J l by 2-5 mEq/1 for 10 mm Hg l pC02](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-69-320.jpg)

![include phosphates, sulfates and proteins (e.g. albumin).

Under typical conditions, unmeasured anions exceed

unmeasured cations; this is referred to as the anion gap

and can be represented by the following formula:

Anion gap = (Na+) - (Cl-+ HC03)

The anion gap is normally8 to 16 mEq/1. When a strong

acidisaddedtoorproducedinthebody, hydrogenionsare

neutralized by bicarbonate, resulting in a fall in bicarbo

nate. These acids include inorganic (e.g. phosphate or

sulfate), organic (e.g. ketoacids or lactate) or exogenous

(e.g. salicylate) acids incompletely neutralized by bicar

bonate. The accompanying unmeasured anion results in

increasedaniongapproportionaltothefallinbicarbonate.

Incontrast, when the bicarbonate is lost from the body, no

new anion is generated; therefore there is a reciprocal

increaseinchlorideions (proportionaltothefallinbicarbo

nate) resulting in normal anion gap. Hypoalbuminemia is

the most common cause of a low anion gap. Albumin

represents about half of the total unmeasured anion pool;

foreverydecreaseof 1 g/dlofplasmaalbumin, theplasma

anion gap decreases by 2.5 mEq/1.

Metabolic Acidosis

Metabolic acidosis is an acid-base disorder characterized

by a decrease in serum pH that results from either a loss

in plasma bicarbonate concentration or an increase in

hydrogen ion concentration (Table 5.12). Primary meta

bolic acidosis is characterized by an arterial pH of less

than 7.35 due to a decrease in plasma bicarbonate in the

absence of an elevated PaC02. If the measured PaC02 is

Table 5.12: Causes of metabolic acidosis

Normal anion gap (hyperchloremic acidosis)

Renal loss ofbicarbonate

Proximal (type 2) renal tubular acidosis, carbonic anhydrase

inhibitors (e.g. acetazolamide), tubular damage due to drugs

or toxins

Gastrointestinal bicarbonate loss

Diarrhea, ureteral sigmoidostomy, rectourethral fistula,

fistula or drainage of small bowel or pancreas

Decreased renal hydrogen ion excretion

Renal tubular acidosis type 1 and type 4 (aldosterone

deficiency)

Potassium sparing diuretics

Increased hydrogen chloride production

Parenteral alimentation, increased catabolisrn of lysine and

arginine

Ammonium chloride ingestion

Elevated anion gap

Increased acid production/accumulation: Sepsis, shock, poisonings

(ethanol, methanol, ethylene glycol); inborn errors of

metabolism

Ketoacidosis: Diabetic ketoacidosis, starvation

Exogenous acids: salicylates, iron, isoniazid, paraldehyde

Failure ofacid excretion: Acute or chronic renal failure

Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances

-

higher thantheexpectedPaCO2, aconcomitant respiratory

acidosis is also present (caused by a depressed mental

state, airway obstruction or fatigue). Acutely, medullary

chemoreceptors compensate for metabolic acidosis

through increase in alveolar ventilation, which results in

tachypnea and hyperpnea that washes off CO2 and

corrects pH.

Calculation of plasma anion gap helps to classify

metabolic acidosis into thosewithelevated anion gap (i.e.

>12 mEq/1 as in increased acid production or decreased

losses) and those with normal anion gap (i.e. 8-12 mEq/1

as in gastrointestinal or renal loss of bicarbonate or when

hydrogen ions cannot be secreted because of renal failure)

(Table 5.12).

Another useful tool in the evaluation of metabolic

acidosis with normal anion gap is urinary anion gap.

Urinary anion gap = urinary [Na+]+ [K+] - [Cl-]

Urinary anion gap is negative in patients with diarrhea

regardless of urinarypH, andurinaryaniongapis positive

in renal tubular acidosis. An elevated osmolal gap (>20

mOsm/kg) with metabolic acidosis suggests the presence

of osmotically active agents such as methanol, ethylene

glycol or ethanol.

Clinical Features

Initially, patients with a metabolic acidosis develop a

compensatory tachypnea and hyperpnea, which may

progress if theacidemiaissevere, and the child can present

with significant work of breathing and distress (Kussmaul

breathing). An increase in H+ concentration results in

pulmonary vasoconstriction, which raises pulmonary

artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance.

Tachycardia is the most common cardiovascular effect

seen with mild metabolic acidosis. Cerebral vasodilation

occurs as a result ofmetabolicacidosis and maycontribute

to an increase in intracranial pressure. Acidosis shifts the

oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve to the right,

decreasing hemoglobin's affinity for oxygen. During

metabolic acidosis, excess hydrogen ionsmove toward the

intracellularcompartment andpotassium moves out of the

cell into the extracellular space. Untreated severe

metabolicacidosis maybeassociated with life-threatening

arrhythmias, myocardial depression, respiratory muscle

fatigue, seizures, shock and multiorgan failure.

Treatment

It is important to identify the cause of metabolic acidosis

as most cases resolve with correction of the underlying

disorder. The role of alkali therapy in acute metabolic

acidosis is limited. It is definitely indicated in some

situations, e.g. salicylate poisoning, inborn errors of

metabolism, or in those with pH below or equal to 7.0 or

[HC03-J less than 5 mEq/1, as severe acidosiscanproduce

myocardial dysfunction. The amount of bicarbonate

required is: Body weight (kg) x base deficit x 0.3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-71-320.jpg)

![__E_s_s_ e_n_t_ia_i_P_e _d_ia_t_ri_c_

s __________________________________

One ml of 7.5% sodium bicarbonate provides 0.9 mEq

bicarbonate. The recommendation is to replace only half

of the total bicarbonate deficit during the first few hours

of therapy. This amount is given as continuous infusion

over two hours. Rapid correction of acidosis with sodium

bicarbonate can lead to extracellular volume expansion,

exacerbating pulmonary edema in patients with cardiac

failure. In the latter, the rate of infusion should be slower

or sodium bicarbonate replaced by THAM [dose (ml) =

weight (kg) x base deficit] which is infused over 3-6 hr. If

hypernatremia is a concern, sodium bicarbonate may be

used as part of the maintenance intravenous solution.

During correction of acute metabolic acidosis, the effect

of sodium bicarbonate in lowering serum potassium and

ionized calcium concentrations must also be considered

and monitored. Since bicarbonate therapy generates large

amount of CO2, ventilation should increase proportion

ately otherwise this might worsen intracellular acidosis.

The inability to compensate may be especially important

in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis who are at risk for

cerebral edema. In diabetic ketoacidosis, insulin therapy

generally corrects the acidosis.

In newborns, frequent administration of hypertonic

solutionssuchassodiumbicarbonatehaveledtointracranial

hemorrhage resulting from hyperosmolality and resultant

fluid shifts from the intracellular space. Children with

inherited metabolicabnormalities,poisoning,orrenalfailure

may require hemodialysis.

Mild to moderate acidosis in renal failureor renal tubular

acidosis improves on oral alkali therapy, the dose being 0.5

to 2 mEq/kg/day of bicarbonate in 3-4 divided doses. In

cases of acidosisduetovolumedepletion,thevolumedeficit

should be corrected.

Metabolic Alkalosis

Metabolic alkalosis (pH >7.45) is an acid-base disturbance

caused by elevation in the plasma bicarbonate (HC03)

concentration in the extracellular fluid that results from a

net loss of acid, net gain of base or loss of fluid with more

chloride than bicarbonate. There are 2 types of metabolic

alkalosisclassified based on the amount of chloride in the

urine, i.e. chloride-responsive or chloride resistant

(Table 5.13). Chloride-responsive metabolic alkalosis

shows urine chloride levels of less than 10 mEq/1 and is

characterized by decreased ECF volume and low serum

chloride levels, such as occurs with vomiting or use of

diuretics.This type responds to administration of chloride

salt (usually as normal saline). Chloride resistant metabolic

alkalosis is characterized by urine chloride levels of more

than 20 mEq/l. Primary aldosteronism is an example of

chloride-resistant metabolic alkalosis and this type resists

administration of therapy with chloride.

The body compensates for metabolic alkalosis through

buffering of excessbicarbonateandhypoventilation. Intra

cellular buffering occurs through sodium-hydrogen and

potassium-hydrogen ion exchange, with eventual

Table 5.13: Causes of metabolic alkalosis

Chloride responsive

Gastric fluid loss (e.g. vomiting, nasogastric drainage)

Volume contraction (e.g. loop or thiazide diuretics, metolazone)

Congenital chloride diarrhea, villous adenoma

Cystic fibrosis

Post-hypercapnia syndrome (mechanically ventilated patients

with chronic lung disease)

Chloride resistant

Primary aldosteronism (adenoma, hyperplasia)

Renovascular hypertension, renin secreting tumor

Bartter and Gitelman syndromes

Apparent mineralocorticoid excess

Glucocorticoid remediable aldosteronism

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (11�- and 17a-hydroxylase

deficiency)

Liddle syndrome

Excess bicarbonate ingestion

formation of CO2 and water from HC03.Within several

hours, elevated levels of HC03- and metabolic alkalosis

inhibit the respiratorycenter, resulting in hypoventilation

and increased pC02 levels. This mechanism produces

a rise in pC02 of as much as 0.7 to 1 mm Hg for each

1 mEq/1 increase in HC03.

Clinical Features

Signs and symptoms observed with metabolic alkalosis

usuallyrelatetothespecificdisease processthatcausedthe

acid-base disorder.Increased neuromuscular excitability

(e.g. from hypocalcemia), sometimes causes tetany or

seizures.Generalizedweaknessmaybenotedif thepatient

also has hypokalemia. Patients who develop metabolic

alkalosis from vomiting can have symptoms related to

severe volume contraction, with signs of dehydration.

Although diarrhea typically produces a hyperchloremic

metabolic acidosis, diarrheal stools may rarely contain

significant amountsofchloride,asinthecaseofcongenital

chloride diarrhea. Children with this condition present at

birthwithwatery diarrhea,metabolic alkalosis, andhypo

volemia. Weight gain and hypertension may accompany

metabolic alkalosis that results from a hyper

mineralocorticoid state.

Treatment

The overall prognosis in patients with metabolic alkalosis

depends on the underlying etiology. Prognosis is good

with prompt treatment and avoidance of hypoxemia. Mild

or moderate metabolic alkalosis or alkalemia rarely

requires correction.Forsevere metabolic alkalosis, therapy

should address the underlying disease state, in addition

to moderating the alkalemia. The initial target pH and

bicarbonate level in correcting severe alkalemia are

approximately 7.55 and 40 mEq/1, respectively.

Therapy with diuretics (e.g. furosemide, thiazides)

should be discontinued. Chloride-responsive metabolic

alkalosis responds to volume resuscitation and chloride](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-72-320.jpg)

![__E_s_s_e_n_ t_ia_l_P_e_d_ i_a _tr_ic_s_________________________________

with chronic hypervitaminosis may have dermatitis,

alopecia, hepatosplenomegalyand/or hyperostosis.When

taken by pregnant women in early gestation at daily levels

ofmorethan 7500 µg,fetal anomalies andpoor reproductive

outcomes are reported. The WHO recommends that

vitamin A intake during pregnancy should not exceed

3000 µg daily or 7500 µg every week.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is the generic term for secosteroids,which have

an important role in maintaining calcium andphosphorus

homeostasis. Secosteroids have three intact rings and one

open ringwithconjugateddouble bonds. Various vitamin

D metabolites differ in the side chains attached to the

fourth ring. Vitamin D is a group of precursors of a

hormone, 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, synthesized and

secreted by the kidneys under thecontrol of parathormone

and tissue phosphate levels (Fig. 7.2). Dietary vitamin D

is essential if the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3 is

insufficient. When deficient, disease manifestations

include rickets, with defective mineralization of growing

bone, and osteomalacia with impaired mineralization of

non-growing bones.

Absorption, metabolism and mechanism of action

Vitamin D refers to two prohormones, vitamin D2 (ergo

calciferol; derived from plants) and D3 (cholecalciferol,

available from animal sources) and their derivatives.

Vitamin D is absorbed in the duodenum by an active

transport system. In the enterocyte, vitamin D is incor

porated into chylomicrons and transported to the liver,

where its hydroxylation take place to form 25-hydroxy

vitaminD2 [250HD2]and25-hydroxyvitaminD3 [250HD3],

known as ercalcidiol and calcidiol respectively. This

hydroxylation is substrate dependent and without any

negative feedback control. Calcidiol is released into the

bloodstreamandhasa biological half-life ofapproximately

3 weeks. Subsequent hydroxylation by la-hydroxylase in

the proximal renal tubule leads to formation of 1,25-

dihydroxyvitamin D2 [l,25(0H)iD2] or ercalcitriol and

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [l,25(0H)iD3] or calcitriol(Fig.

7.2). While circulating l,25(0H)iD almost exclusively

results from renal production, extrarenal conversion also

takes place in the skin, colon, macrophages, vascular

smooth muscle cells, bone and parathyroid glands. Renal

conversion is regulated by parathormone, calcitonin,

calcium and phosphate; and inhibited by calcitriol and

the phosphaturic hormone, fibroblast growth factor 23

(FGF-23). A negative relationship exists between serum

250HD and parathormone levels (Fig. 7.2). Vitamin D

supplementation suppresses serum parathormone and

increases bone mineral density.

Active vitamin D affects calcium homeostasis through

its action on the intestine, kidney and bones. In the

intestine,thehormone induces calciumtransport proteins

and an intracellular calcium-binding protein (calbindin)

which aid in transport of calcium across the enterocyte.

In the kidney, the hormone enhances calcium resorption

in the tubule by a similar mechanism. It also inhibits the

activity of la-hydroxylase and stimulates renal 24-

hydroxylaseactivitythat inactivates both the substrate and

calcitrio1.

Dehydrocholesterol

�

Dietary (vitamin 02, 03)

�V�mioD/

l;�!:�roxylase

24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D .__

24_

·h

-

yd_rox_y1_as_e

_ 25-hydroxyvitamin D

(inactive)

Bone

Increased mineralization

-

I

1a·hydroxylase Parathormone

+l Kidney

1 + Low phosphorus

I •::.-------Fibroblast growth factor

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D ----• Decrease parathormone

Kidney

Increased calcium and

phosphate reabsorption

Intestine

Increased calcium and

phosphate absorption

Fig. 7.2. Vitamin D metabolism. Serum levels of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23 are elevated in response to increased serum phosphate and

also inhibit the production of parathormone](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-98-320.jpg)

![__

e_s_s_e_n_ti_a

_1_P_e_d_1a_t_ri

_cs-------------------------------

Fig. 7.3: A 5-yr-

old child with rickets with wide wrists and bow legs

Fig. 7.4: Radiograph of wrist in 4-yr-old boy with rickets. Note

widening, cupping and fraying at the metaphyseal ends of forearm

bones

Table 7.2: Vitamin D levels in serum

Deficient

Insufficient

Optimal

High

Toxic

25-hydroxyvitamin D level (ng/ml)

Less than 10

10-20

20-60

60-90

Greater than90

daily for 10 days) followed by a maintenance dose of

400-800 IU/day and oral calcium supplements (30-

75mg/kg/day)for2 months. Followingadequatetherapy,

most patients with vitamin D deficiency rickets show

radiological evidence of healing (Fig. 7.5)within 4 weeks.

Reduction in blood levels of alkaline phosphatase and

resolution of clinical signs occur slowly. If radiologic

healing cannotbedemonstrated, despite 1 -

2large dosesof

vitamin D, patients should be evaluated for refractory

rickets (Fig. 7.6).

Familial Hypophosphatemic Rickets

This is the most commonly inherited form of refractory

rickets, being inheritedas X-linked dominantwithvariable

penetrance. Sporadic instances are frequent and an

autosomal recessive inheritance has also been reported.

Pathogenesis The gene for X-linked hypophosphatemic

rickets is termed the PHEX gene (phosphate regulating

gene with homology to endopeptidases on the X chromo

some). Theunderlying defect involves impairedproximal

tubular reabsorption of phosphate. Despite hypophos

phatemia the blood levels of 1,25(0H)z03 are low, which

Fig. 7,5: Healing of the growth plate after vitamin D therapy

Refractory rickets

Serum phosphate]

I

+

Low or Normal High

+

Blood pH]

I

Chronic kidney disease

Lowl Normal

...

Renal tubular acidosis Serum PTH, calcium

i i

High PTH, low or normal calcium] Normal PTH, normal calcium

+ +

Vitamin D dependent rickets Hypophosphatemic rickets

Fig. 7.6: Biochemical evaluation of a child with refractory rickets](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-100-320.jpg)

![some instances, the trachea in non-vigorous baby born

through meconium stained liqor). If necessary, insert an

endotracheal (ET) tube to ensure an open airway.

B-Breathing: Tactile stimulation to initiate respirations,

positive-pressure breaths using either bag and mask or

bag and ET tube when necessary.

C-Circulation: Stimulate and maintain the circulation of

blood with chest compressions and medications as

indicated.

Resuscitation Algorithm

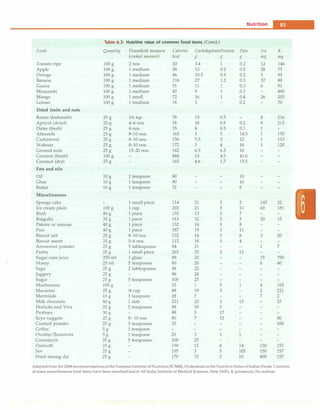

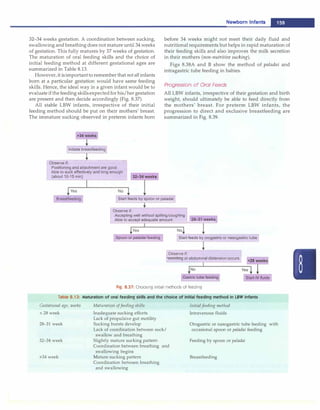

Figure 8.2 presents the algorithm of neonatal resuscitation.

At the time of birth, one should ask three questions about

the newborn:

i. Term gestation?

ii. Breathing or crying?

iii. Good muscle tone? (flexed posture and active

movement of baby denotes good tone)

Birth

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

30 sec

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

60 sec

Term gestation?

Breathing or crying?

Good tone?

No

Provide warmth, clear airway

if necessary, dry, stimulate

Heart rate below 100,

gasping or apnea?

Yes

1

[

Positive pressure ventilation

]

SpO, monitoring

!

1Heart rate below 100?1

Yes

[ Take ven� �ective step7")

_!

Heart rate below 60?

Yes!

___ -

r-- Consider intubation ::i

Chest compressions

Coordinate with positive pressure ventilation

!

L!:!.eart rate below 60?J

Yesu

IV epinephrine

Yes

No

No

Newborn Infants -

If answers to all the three questions are 'Yes', the baby

does not require any active resuscitation and "Routine

care" should be provided. Routine care consists of four

steps:

i. Warmth: Provided by putting the baby directly on the

mother's chest in skin-to-skin contact.

ii. Clearingofairway ifrequired: Done bywipingthe baby's

mouth and nose using a clean cloth. No need to suction

routinely.

iii. Dry the baby

iv. Ongoing evaluation for vital parameters. Helping

mother in breastfeeding will facilitate easy transition

to extrauterine environment.

If answer to any of the three questions is "No", the baby

requires resuscitation. After cutting the cord, the baby

should be subjected to a set of interventions known as

Initial steps.

Routine care

Provide warmth

Clear airway, if necessary Assessment

Dry

Keep with mother

Ongoing evaluation

rNo

,"Labored breathing Evaluation

�� pe2!.stent cyanosis?

Yes

Clear airway, SpO, monitoring

]

Co�erCPAP

Evaluation

care

Targeted SpO,after birth

1 minute: 60-65%

2 minutes: 65-70%

3 minutes: 70-75% Evaluation

4 minutes: 75-80%

5 minutes: 80-85%

10 minutes: 85-95%

Fig. 8.2: The algorithm of neonatal resuscitation. CPAP continuous positive airway pressure; PPV positive ventilation; Sp02 saturation of oxygen.

(Adapted with permission from American Academy of Pediatrics 2010)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-113-320.jpg)

![- Essential Pediatrics

antibodies (IgM and IgG) develop at the time symptoms

occur, usually before the development of jaundice. IgM

anti-HEY titer declines rapidly during early convale

scence,whileIgG anti-HEYpersistsfor long duration and

provides protection against subsequent infections.

Treatment

As no specific therapy is capable of altering the course of

acute hepatitis E infection, prevention is the most effective

approach against the disease.

Prevention

Good personal hygiene, high quality standards for public

water supplies and proper disposal of wastehave resulted

in a low prevalence of HEV infections in developed

countries. At present, thereare no commercially available

vaccines for the prevention of hepatitis E.

Hepatitis due to other Viruses

Certain cases of post-transfusion (10%) and community

acquired hepatitis (20%) are of unknown origin. Three

viruses are potentially associated with liver disease but

no conclusive evidence exists to support them as a cause

for these cases. These viruses are HGV/GB virus C, TT

virus and SEN virus.

Suggested Reading

Aggarwal R, Jameel S. Hepatitis E. Hepatology 2011 Dec;54:2218-26

Dengue Infections

Dengue fever is an acute illness characterized by fever,

myalgia, arthralgia and rash. Severe dengue infection is

characterized by abnormalities in hemostasis and by

marked leakage of plasma from the capillaries; the latter

may lead to shock (dengue shock syndrome).

Epidemiology

The global prevalence of dengue has grown dramatically

in recent decades. The disease is now endemic in more

than 100 countries in Africa, the Americas, the Eastern

Mediterranean, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific.

WHO currently estimates there may be 50 million cases

of dengue infection worldwide every year. During

epidemics of dengue, attack rates among susceptible are

often40-50%,but mayreach80-90%. An estimated 500,000

cases of severe dengue infection require hospitalization

each year, of which very large proportions are children.

Without proper treatment in severe dengue infection

[earlier called dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) dengue

shock syndrome (DSS)] case fatality rates can exceed 20%.

The spread of dengue is attributed to expanding

geographic distribution of the four dengue viruses andof

their mosquito vectors, the most important of which is

the predominantly urban species Aedes aegypti. A rapid

rise in urbanpopulationsis bringing evergreaternumbers

of people into contact with this vector, especially in areas

that are favorable for mosquito breeding, e.g. where

household water storage is common and where solid

waste disposal services are inadequate.

Virus. Dengue fever is causedbyinfectiondue to any of the

four serotypes of dengue viruses. Dengue viruses are

arboviruses that belong to the family Flaviviridae. The

envelop protein bears epitopes that are unique to the

serotypes;theantibodiestotheseuniqueepitopesneutralize

by interfering with the entry of the virus into the cells.

Transmission. Dengue viruses are transmitted to humans

through the bites of infected female Aedes mosquitoes.

Mosquitoes generally acquire the virus while feeding on

the blood of an infected person. After incubation for 8-10

days, an infected mosquito is capable, during probing and

blood feeding, of transmitting the virus, to susceptible

individuals for the rest of its life. Infected female

mosquitoes may also transmit the virus to their offspring

by transovarial transmission, but the role of this in

sustaining transmission of virus to humans has not yet

been delineated.Humans are the main amplifying host of

the virus, although studies have shown that in some parts

of the world monkeys may become infected and perhaps

serve as a source of virus for mosquitoes. The virus

circulates inthebloodof infected humans fortwo to seven

days, at approximately the same time as they have fever;

Aedes mosquitoes may acquire the virus when they feed

on an individual during this period.

Pathophysiology

The major pathophysiologic changes that determine the

severity of disease in severe dengue infection and

differentiate it from dengue fever are plasma leakage and

abnormal hemostasisleading to rising hematocrit values,

moderate to marked thrombocytopenia and varying

degrees ofbleeding manifestations. Thecause of abnormal

leakage of plasma is not entirely understood. However,

rapid recovery without residual abnormality in vessels

suggests it to be the result of release and interaction of

biological mediators, which are capable of producing

severe illness with minimal structural injury.

It has been observed that sequential infection with any

two of the four serotypes of dengue virus results in severe

dengue infections in an endemic area. How a second

dengue infection causes severe disease andwhyonlysome

patients get severe disease remains unclear.It is suggested

that the residual antibodies produced during the first

infection areabletoneutralize a secondviralinfection with

the same serotype. However, when no neutralizing

antibodies are present (i.e. infection due to another

serotype of dengue virus), the second infection is under

the influence of enhancing antibodies and the resulting

infection and disease are severe. An alternative expla

nation is that certain strains (South-East Asian) of the

dengue virus may be inherently capable of supporting](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-210-320.jpg)

![__

E_s_s_e _n_t.ia•l•P•e•d-i

a_ t_r.ic_s_________________________________

Severe dengue fever

[A�ssme;;t° of shock

Hypotension

�+

loss 1111

..

[u'n'rec"ord� blood pressure j

+

DSSIV

Ringer lactate 20 ml/kg bolus; up to 3 boluses

Ringer lactate (RL) 10-20 ml/kg/hr]

,-- • Assessment1------------�

�Noimp�

Gradually decrease �ocrit increasedJ<14------'

jHe

matocrit !ecreasedj

Ringer lactate infusion with 1 -- T

monitoring as in Fig. 10.9 't 't

-r Colloids 10 ml/kg [Blood transfusio�

I •fAs-;;sment

1

4 I

I

.�---------'------..

Improved � improveme-;it]

Look for anemia, acidosis, myocardial dysfunction; treat accordingly

Fig. 10.10: Algorithm for management of severe dengue fever. DSS dengue shock syndrome

illness. Heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and

pulse pressure should be monitored every 30 min till the

patient is stable, thereafter every 2-4 hr should be

continued as long as the child is in the hospital. In critically

ill children, central venous pressure and accurate urine

output with an indwelling urinary catheter should be

monitored. Absolute platelet counts should be checked

once a day till it shows a rising trend.

Prognosis

Dengue fever is a self-limited disease but the mortality in

severe dengue may be as high as 20-30% if left untreated.

Early recognition of illness, careful monitoring and

appropriate fluid therapy alone has resulted in consi

derable reduction ofcase fatality rate to less than 1 percent.

Early recognition of shock is of paramount importance as

the outcome of a patient with DSS depends on the duration

of shock. If shock is identified when pulse pressure starts

getting narrow and intravenous fluids are administered

at this stage, the outcome is excellent.

Prevention

Preventive measures are directed towards elimination of

adult mosquitoes and their larvae. During epidemics aerial

spraying or fogging with malathion is recommended for

control of adult mosquitoes. However, larval control

measures by source reduction anduse of larvicides are even

more crucial. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes breed in and around

human dwellings and flourish in fresh water. Special drives

should be launched during and soon after the rainy season

to interrupt breeding cycle of mosquitoes. There should be

no opportunity for stagnation of water in the bathroom,

kitchen, terrace,lawnandotheropenplaces. The stored water

should be kept covered. Cooperation from every house

owner and public establishment is crucial for the success of

control program. Strong motivationandcommitment on the

part of government and its employees are fundamental pre

requisites for the success of control measures.

Mesocyclops, the shellfish are credited to eat and

effectively eliminate larvae of Aedes aegypti. The strategy

has been used with success by Australian scientists

working in Vietnam by growing shellfish in ponds and

water traps. A live attenuated quadruple vaccine is

undergoing clinical trials but there are concerns whether

vaccine may predispose to development of severe

dengue.

Suggested Reading

Anonymous. Dengue Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment,

Prevention and Control. A joint publication of the World Health

Organization (WHO) and the Special Programme for Research and

Training in Tropical Diseases (TOR), 2009

Kabra SK, Jain Y, Pandey RM, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in

children in the 1996 Delhi epidemic. Trans Royal Society Trop Med

Hygiene 1999;93:294-8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-214-320.jpg)

![---E•s•s•e•n•t-ia•l•P-e.d.ia.t.ri•c•

s----------------------------------

p9, p6; these are derived from the precursor p55), the pol

region, which encodes the viral enzymes (reverse

transcriptase [p51], protease [plO], and integrase [p32]);

and the env region, which encodes the viral envelope

proteins (gp120 and gp41).

The major external viral protein of HIV-1 is a heavily

glycosylated gp120 protein which contains the binding

site for the CD4 molecule, the most common T lymphocyte

surface receptor for HIV. Most HIV strains have a specific

tropism for one of the chemokines: the fusion-inducing

molecule, CXCR-4, which has been shown to act as a co

receptor for HIV attachment to lymphocytes, and CCR-5,

a � chemokine receptor that facilitates HIV entry into

macrophages.

Following viral attachment, gp120 and the CD4

molecule undergo conformational changes, allowing gp41

to interact with the fusion receptor on the cell surface. Viral

fusion with the cell membrane allows entry of viral RNA

into the cell cytoplasm. Viral DNA copies are then trans

cribed from the virion RNA through viral reverse

transcriptase enzyme activityandduplicationof the DNA

copies produces double-stranded circular DNA. Because

the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is error-prone, many

mutations arise, creating wide genetic variation in HIV-1

isolates even within an individual patient. The circular

DNA is transported into the cell nucleus where it is

integrated into chromosomal DNA; this is called as the

provirus. The provirus can remain dormant for extended

periods.

HIV-1transcriptionis followed bytranslation. A capsid

polyproteinis cleaved to produce, among other products,

the virus-specific protease (plO). This enzyme is critical

forHIV-1 assembly. TheRNAgenomeisthen incorporated

into the newly formed viral capsid. As the new virus is

formed, itbudsthrough thecellmembrane andisreleased.

HIV-2 is a rare cause of infection in children. It is most

prevalent in Western and Southern Africa. If HIV-2 is

suspected, a specific test that detects antibody to HIV-2

peptides should be used.

Transmission. Transmission of HIV-1 occurs via sexual

contact,parenteralexposuretoblood,orverticaltransmission

from mother to child. The primary route of infection in the

pediatric population is vertical transmission. Most large

studies in the United States and Europe have documented

mother-to-child transmission rates in untreated women

between 12 and 30%. In contrast, transmission rates in

Africa and Asia are higher, up to 50%.

Vertical transmission of HIV can occur during the

intrauterine or intrapartum periods, or through breast

feeding. Up to 30% of infected newborns are infected in

utero. The highest percentages of HIV-infected children

acquire the virus intrapartum. Breastfeeding is an

important route of transmission, especially in the

developing countries. The risk factors for vertical

transmission include preterm delivery (<34 week

gestation), a low maternal antenatal CD4 count, use of

illicit drugsduringpregnancy, >4 hr durationofruptured

membranes and birthweight <2500 g.

Transfusions of infected blood or blood products have

accounted for a variable proportion of all pediatric AIDS

cases. Heat treatment of factor VIII concentrate and HIV

antibody screening of donors hasvirtually eliminatedHIV

transmission to children with hemophilia. Blood donor

screening has dramatically reduced, but not eliminated,

the risk of transfusion-associated HIV infection. Sexual

contact is a major route of transmission in the adolescent

population.

Natural History

Before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was

available, three distinct patterns of disease were described

in children. Approximately 10-20% of HIV-infected

newborns in developed countries presented with a rapid

disease course, with onset of AIDS and symptoms during

the first few months of life and, if untreated, death from

AIDS-related complications by 4 yr of age. In resource

poor countries, >85% of the HIV-infected newborns may

have such a rapidly progressing disease.

It has been suggested that if intrauterine infection

coincides withthe period of rapid expansion of CD4 cells

in the fetus, it could effectively infect the majority of the

body's immunocompetent cells. Most children in this

group have a positive HIV-1 culture and/or detectable

virus in the plasma in the first 48 hr of life. This early

evidence of viral presence suggests that the newborn was

infected in utero. In contrast to the viralload in adults, the

viral load in infants stays high for at least the first 2 yr of

life.

The majority ofperinatallyinfectednewborns (60-80%)

present with a second pattern-that of a much slower

progression of disease with a median survivaltimeof 6 yr.

Many patients in this group have a negative viral culture

or PCR in the 1st week of life and are therefore considered

to be infected intrapartum. In a typical patient, the viral

load rapidly increases by 2-3 months of age (median

100,000copies/ml) andthenslowlydeclines over a period

of 24 months. This observation can be explained partially

by theimmaturity of theimmune system in newborns and

infants. The thirdpatternofdisease (i.e. longterm survivors)

occurs in a small percentage (<5%) of perinatally infected

children who have minimal or no progression of disease

with relatively normal CD4 counts and very low viral

loads for longer than 8 yr.

HIV-infected children have changes in the immune

system that are similar to those in HIV-infected adults.

CD4 cell depletion may be less dramatic because infants

normally have a relative lymphocytosis. Therefore, for

example, a value of 1,500 CD4 cells/mm3

in children <1

yr of age is indicative of severe CD4 depletion and is

comparableto<200CD4 cells/mm3

inadults. Lymphopenia

is relatively rare in perinatally infected children and is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-216-320.jpg)

![Infections and Infestations -

HIV-infected

pregnant woman

Delivery HIV-exposed infant

(breastfed and nonbreastfed)

J�-::�·

Symptomatic HIV-exposed

child <18 months of age

(not previously diagnosed)

First HIV DNA PCR

ie

Repeat HIV DNA PCR]

to confirm _J

G 8

I

8 l

C --;;;;ative �

PCR tes�

Second PCR after 6-8 weeks I

of stopping breastfeeding or

I

earlier if symptomatic __J

[°s;cond PCR at 6 months

l

l to confirm status J

I

G

Repeat test and refer for

followup

8

Report

HIV negative

Repeat test

and refer for

followup

Fig. 10.11: Diagnosis of infection with HIV in children <18 months. If child is >18-month-old, adult testing strategies may be used

alternative regimen is a combination of stavudine,

lamivudine and nevirapine. The details of the anti

retroviral drugs are shown in Table 10.6. Pediatric fixed

dose combinations have been developed, and these are

administered using a weight-band based dosing system

(NACO guidelines).

Cotrimoxazole Prophylaxis

In resource-limited settings, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis is

recommended for all HIV exposed infants starting at

4-6 weeks of age and continued until HIV infection can be

excluded. Cotrimoxazole is also recommended for HIV

exposed breastfeeding children of any age and cotrimo

xazole prophylaxis should be continued until HIV infection

canbeexcluded byHIVantibodytesting (beyond 18months

of age) or virological testing (before 18 months of age) at

least six weeks after complete cessation of breastfeeding.

All children younger than one yr of age documented to

be living with HIV should receive cotrimoxazole pro

phylaxisregardlessofsymptomsor CD4percentage. After

one yr of age, initiation of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis is

recommended for symptomatic children (WHO clinical

stages 2, 3 or 4 for HIV disease) or children with CD4

<25%. All children who begin cotrimoxazole prophylaxis

(irrespective of whether cotrimoxazole was initiatedin the

first yr of life or after that) should continue until the age

of five yr, when they can be reassessed.

Nutrition

It is important to provide adequate nutrition to HIV

infected children. Many of these children have failure to

thrive. These children will need nutritional rehabilitation.

In addition, micronutrients like zinc may be useful.

Immunization

The vaccines that are recommended in the national

schedule can be administered to HIV infected children

except that symptomatic HIVinfectedchildrenshould not

be given the oral polio and BCG vaccines.

Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT)

The risk of MTCT can be reduced to under 2% by

interventions that include antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis

given to women during pregnancy and labor and to the

infant in the first weeks of life, obstetrical interventions

including elective cesarean delivery (prior to the onset of

labor and rupture of membranes)and complete avoidance

of breastfeeding.

Antiretroviral drug regimens for treating pregnant

women For HIV-infected pregnant women in need of

ART for their own health, ART should be administered

irrespective of gestational age and is continued through

out pregnancy, delivery and thereafter (recommendedfor

all HIV-infected pregnant women with CD4 cell count

<350 cells/mm3

, irrespective of WHO clinicalstaging;and

for WHO clinical stage 3 or 4, irrespective of CD4 cell

count).

Recommended regimen for pregnant women with

indication for ART is combination of zidovudine (AZT),

lamivudine (3TC) and nevirapine (NVP) or efavirenz

(EFV) during antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paediatrics8theditiono-230807055545-451d483c/85/Paediatrics-8th-Edition-O-P-Ghai-pdf-221-320.jpg)

![- Essential Pediatrics

Fig. 10.20: Miliary shadows with right paratracheal adenopathy

is most often made by combination of a positive tuberculin

skin test, chest radiograph, physical examination and

history of contact with adult patient with tuberculosis.

Newerdiagnostic methods such as PCR and serodiagnosis

have not given encouraging results. Newer staining and

culture methods have found their place in the manage

ment of tuberculosis. There is a need to develop better

techniques for diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. A

suggested algorithm for diagnosis of pulmonary tuber

culosis is given in Fig. 10.21.

Treatment

The principles of therapy in children with tuberculosis

are similar to that of adults. The drugs used for treatment

of tuberculosis in children are given in Table 10.9.

Drug Regimens