1. The document discusses ore textures and paragenetic sequences, beginning with definitions and requirements for studying ore textures.

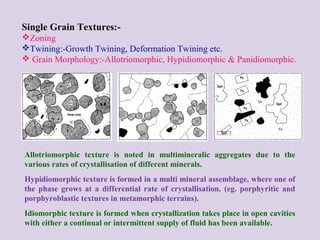

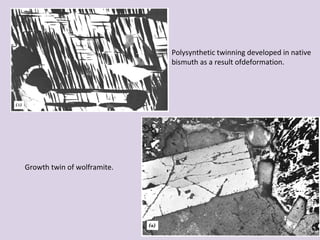

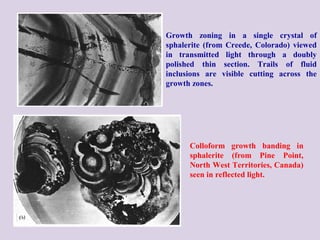

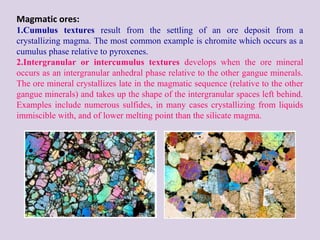

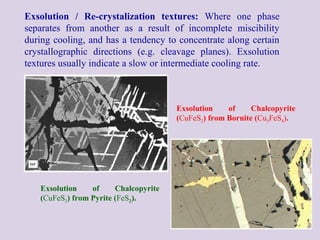

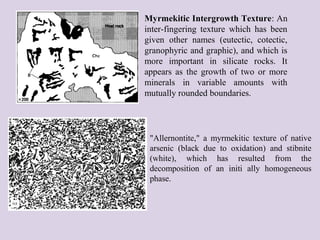

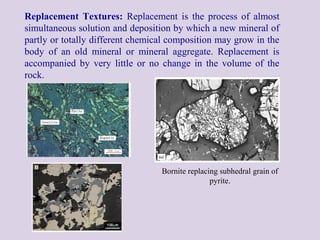

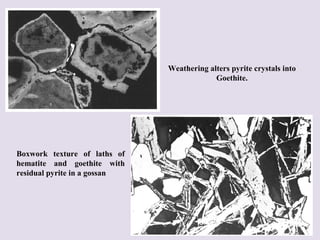

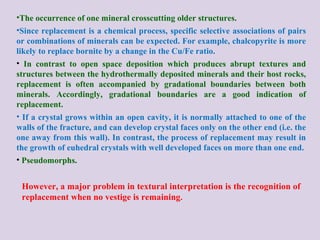

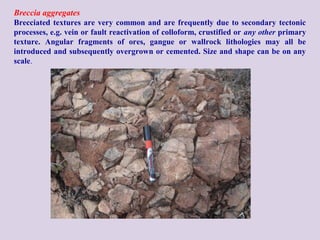

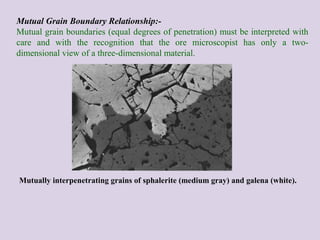

2. It describes various ore textures including single grain textures, magmatic ore textures, open space filling textures, and replacement textures.

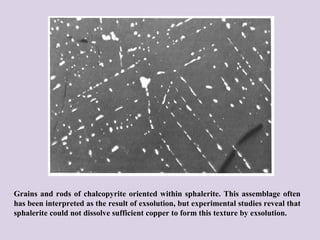

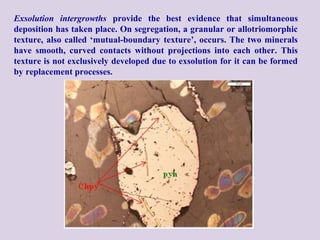

3. The document concludes with a discussion on developing paragenetic sequences by analyzing features like cross-cutting relationships and exsolution textures.