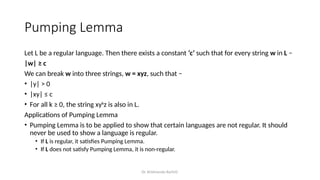

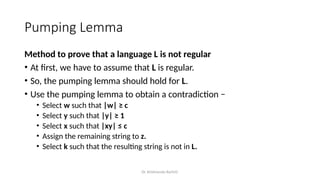

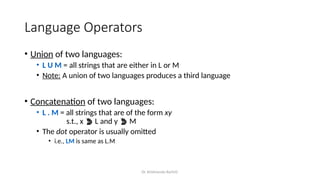

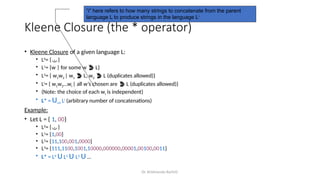

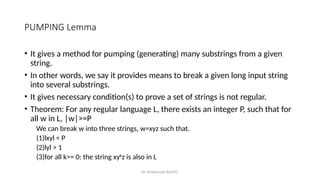

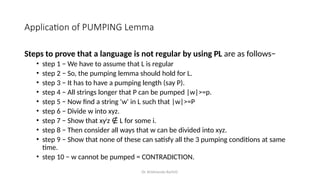

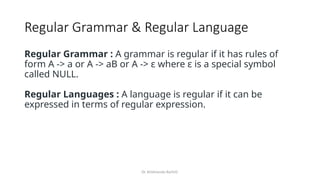

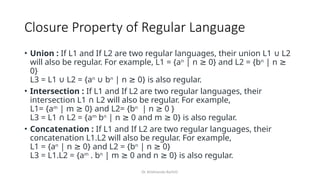

The document provides an introduction to the theory of computation, covering essential terminologies like symbols, alphabets, strings, and languages. It discusses the formation of languages using regular expressions, their relationship with finite automata, and operations on languages like union, concatenation, and Kleene closure. Additionally, the document includes the pumping lemma for testing regularity of languages and addresses equivalence between regular expressions and regular languages.

![Dr. Krishnendu Rarhi©

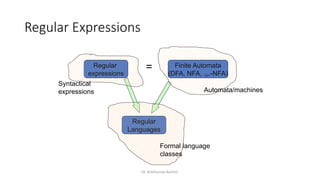

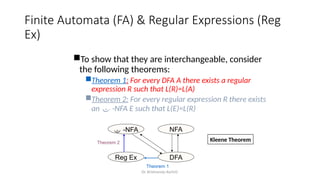

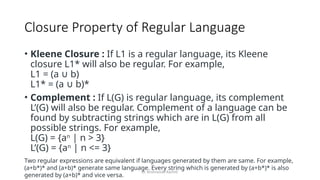

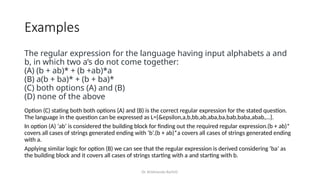

Regular Expressions vs. Finite Automata

• Offers a declarative way to express the pattern of any string we want to accept

• E.g., 01*+ 10*

• Automata => more machine-like

< input: string , output: [accept/reject] >

• Regular expressions => more program syntax-like

• Unix environments heavily use regular expressions

• E.g., bash shell, grep, vi & other editors, sed

• Perl scripting – good for string processing

• Lexical analyzers such as Lex or Flex](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4regularexpressions-250114150327-05f70a02/85/Chapter-4_Regular-Expressions-in-Automata-pptx-7-320.jpg)

![Dr. Krishnendu Rarhi©

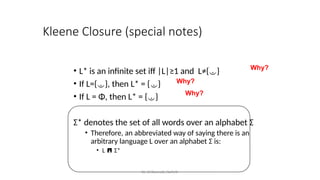

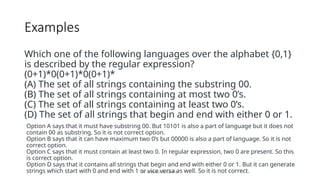

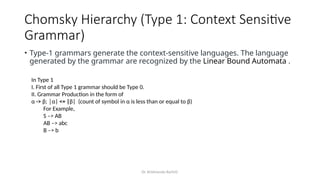

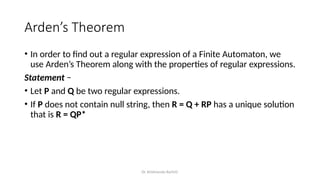

Arden’s Theorem

• Proof −

R = Q + (Q + RP)P [After putting the value R = Q + RP]

= Q + QP + RPP

When we put the value of R recursively again and again, we get the

following equation −

R = Q + QP + QP2

+ QP3

…..

R = Q (ε + P + P2

+ P3

+ …. )

R = QP* [As P* represents (ε + P + P2 + P3 + ….) ]

Hence, proved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4regularexpressions-250114150327-05f70a02/85/Chapter-4_Regular-Expressions-in-Automata-pptx-35-320.jpg)