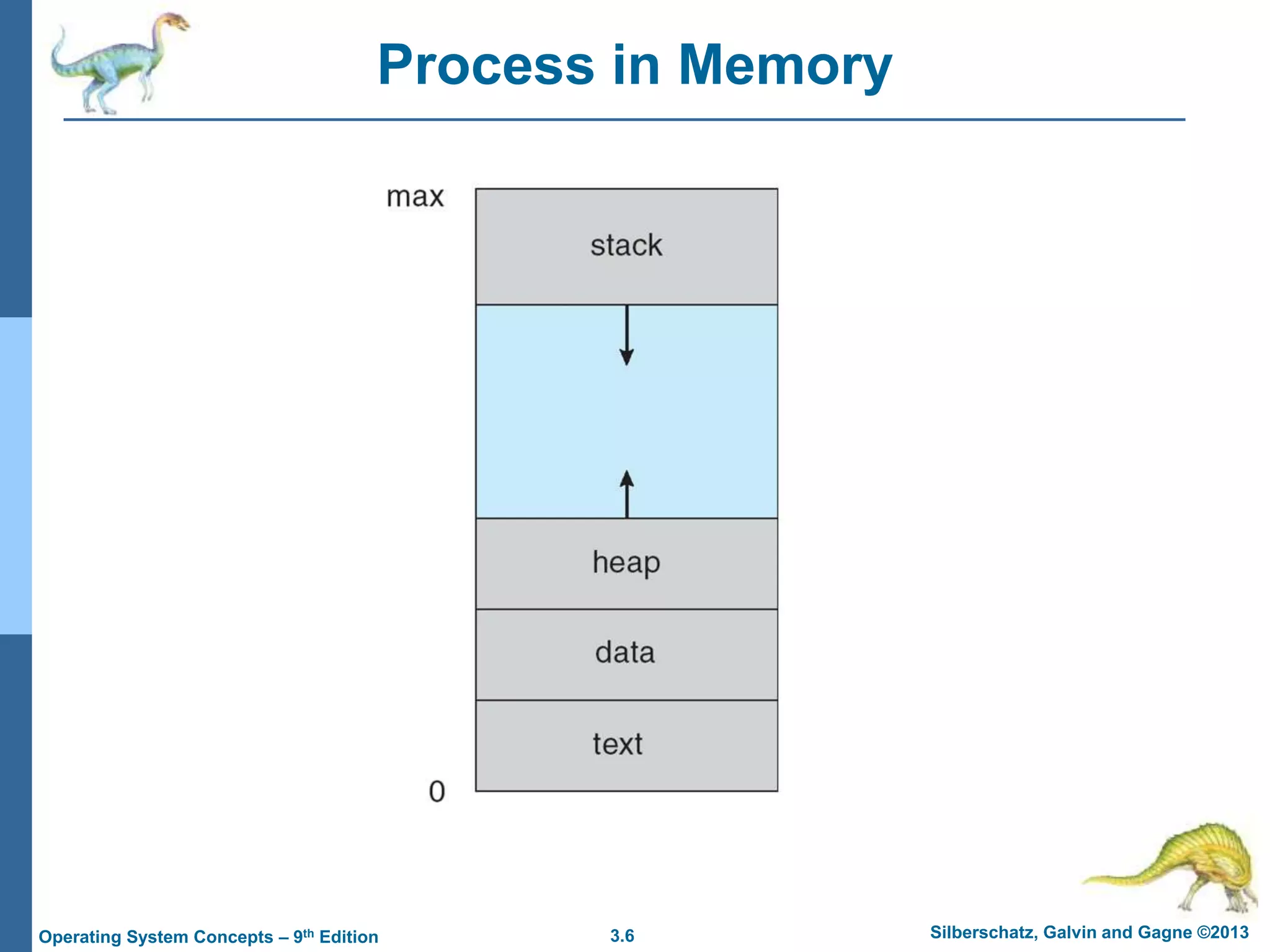

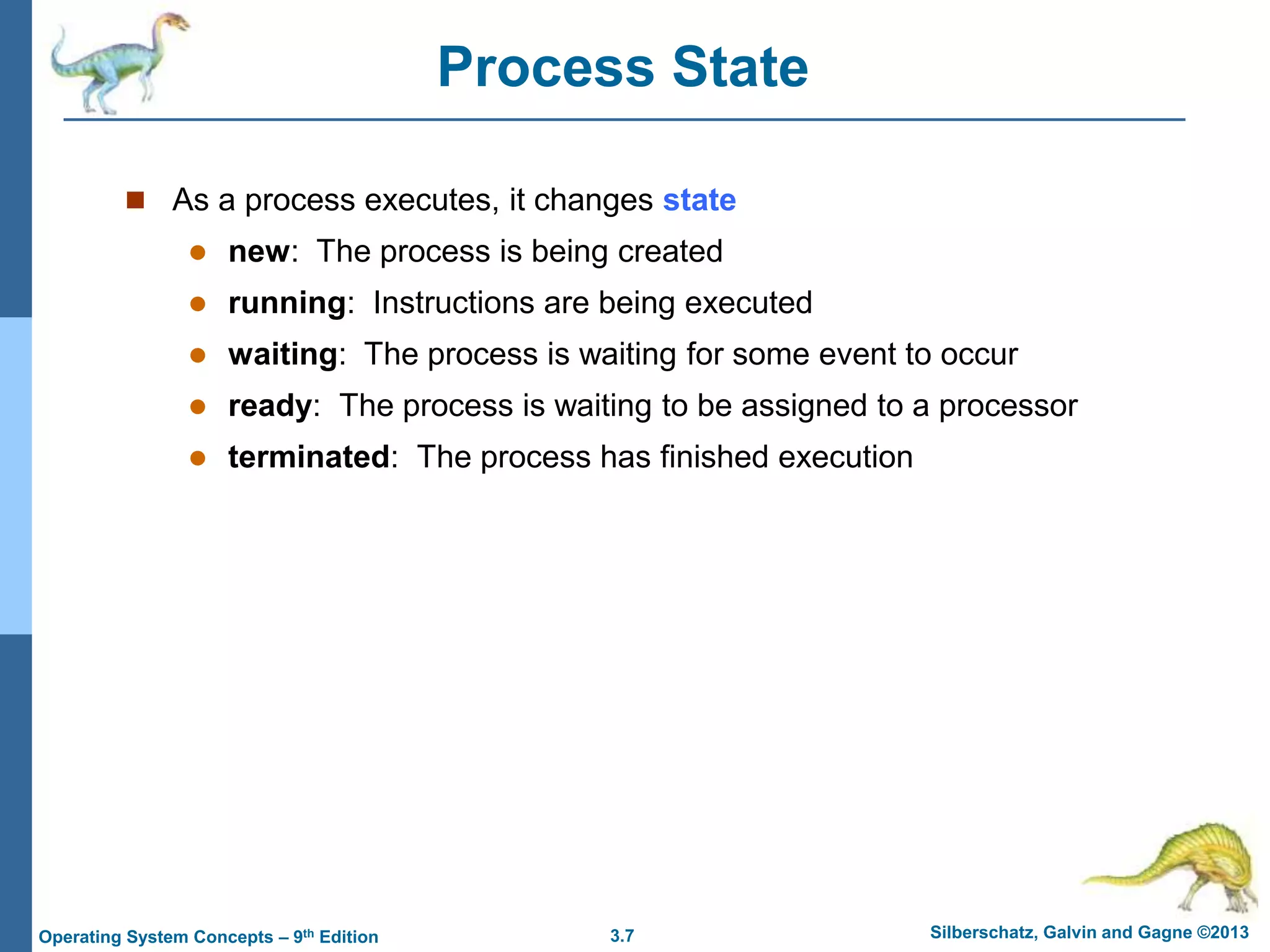

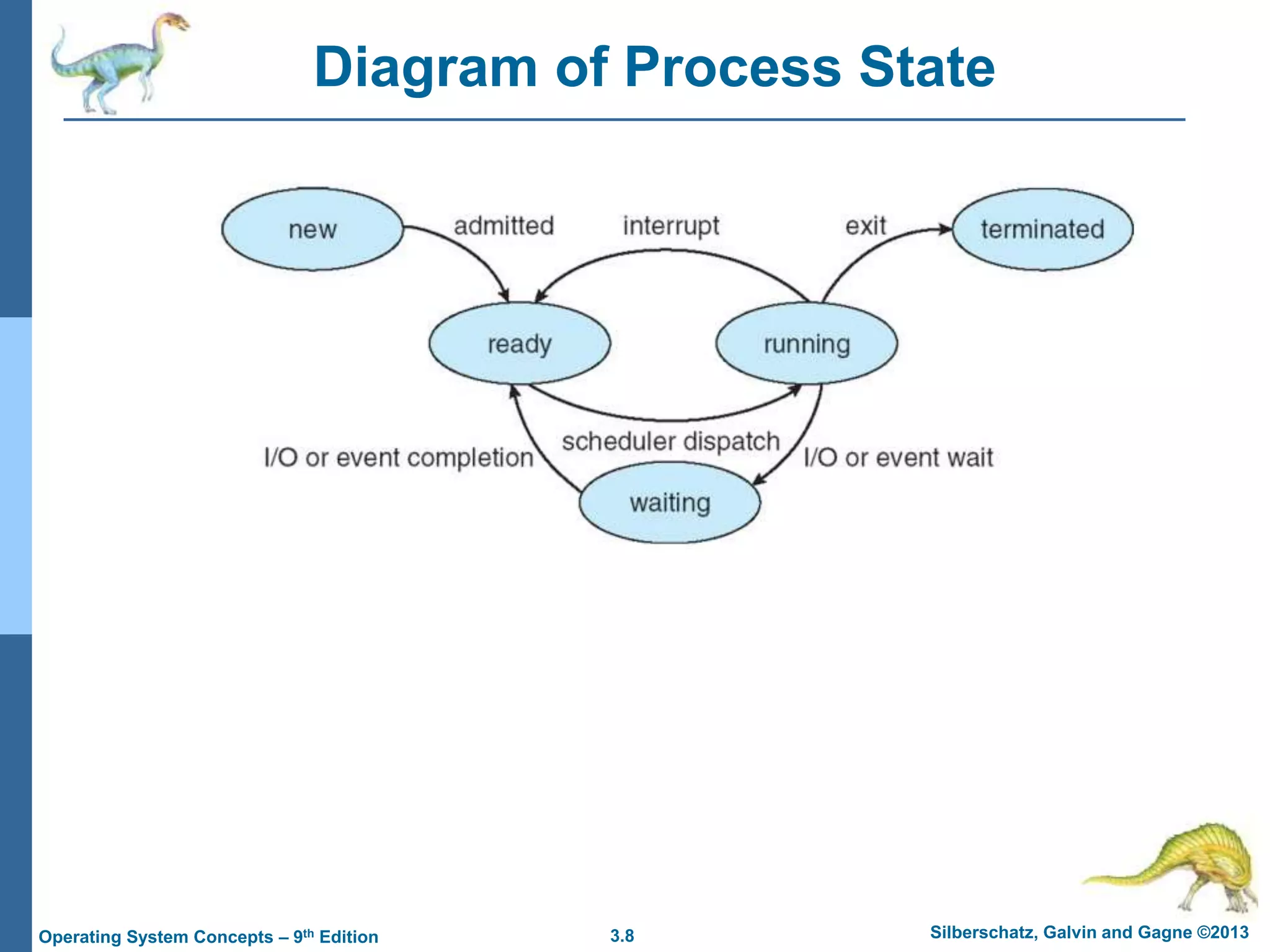

The document discusses the fundamental concepts of processes in operating systems, including process creation, scheduling, and interprocess communication. It emphasizes the significance of processes in executing programs and introduces various states of processes along with methods for communication, such as shared memory and message passing. The document also highlights process management features like scheduling types and process control blocks, providing a comprehensive overview of how processes operate within an operating system.

![3.33 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

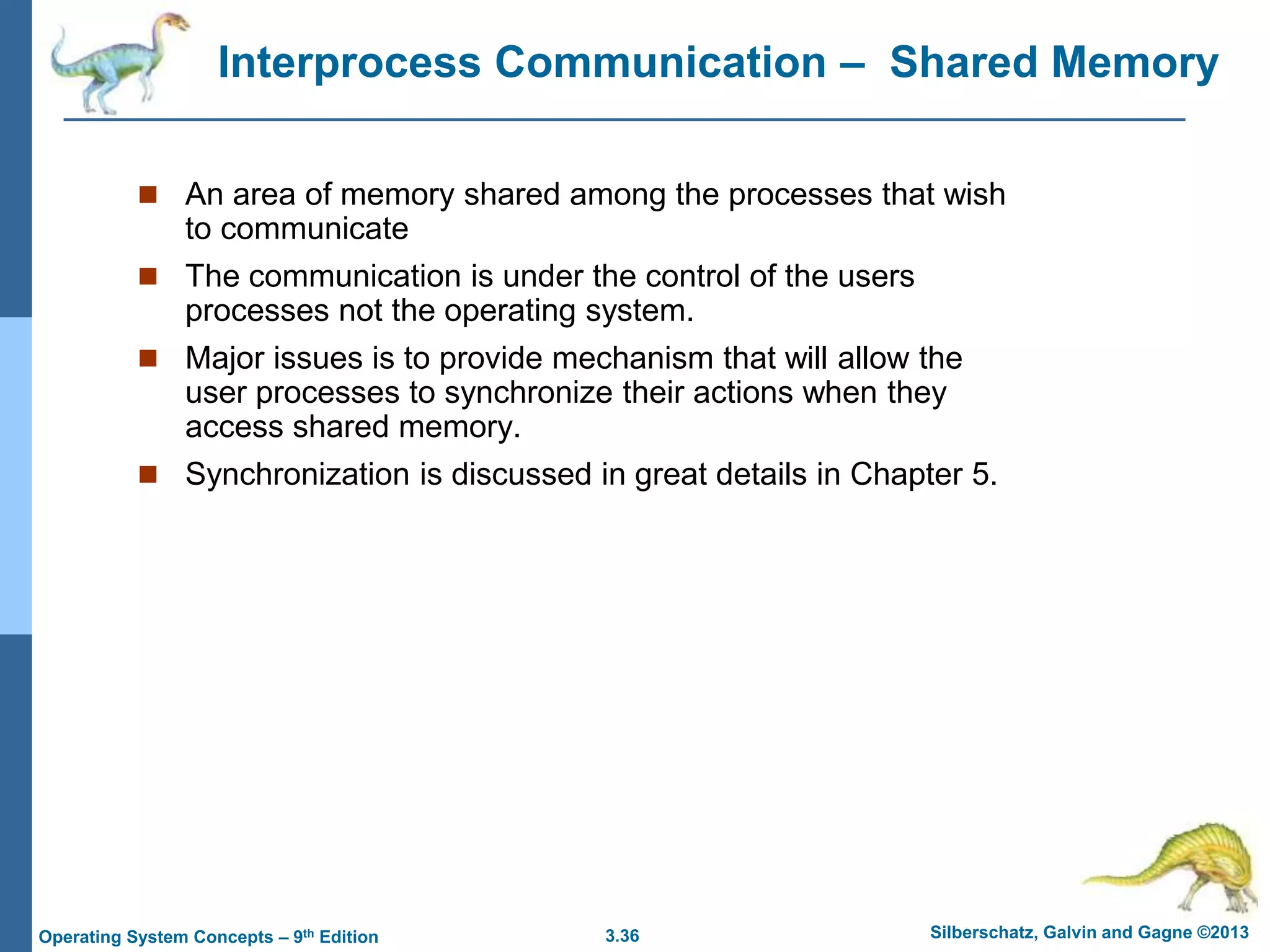

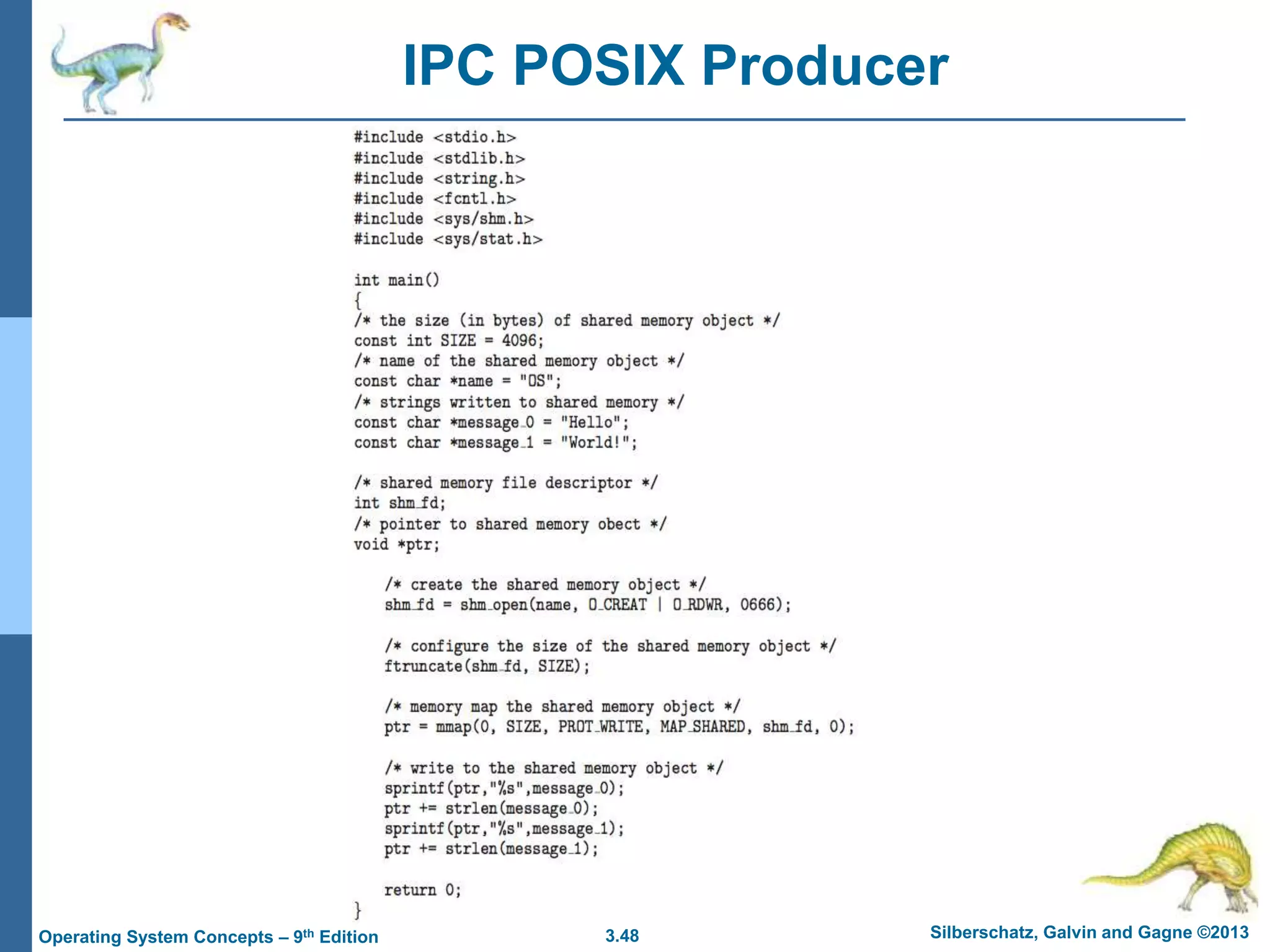

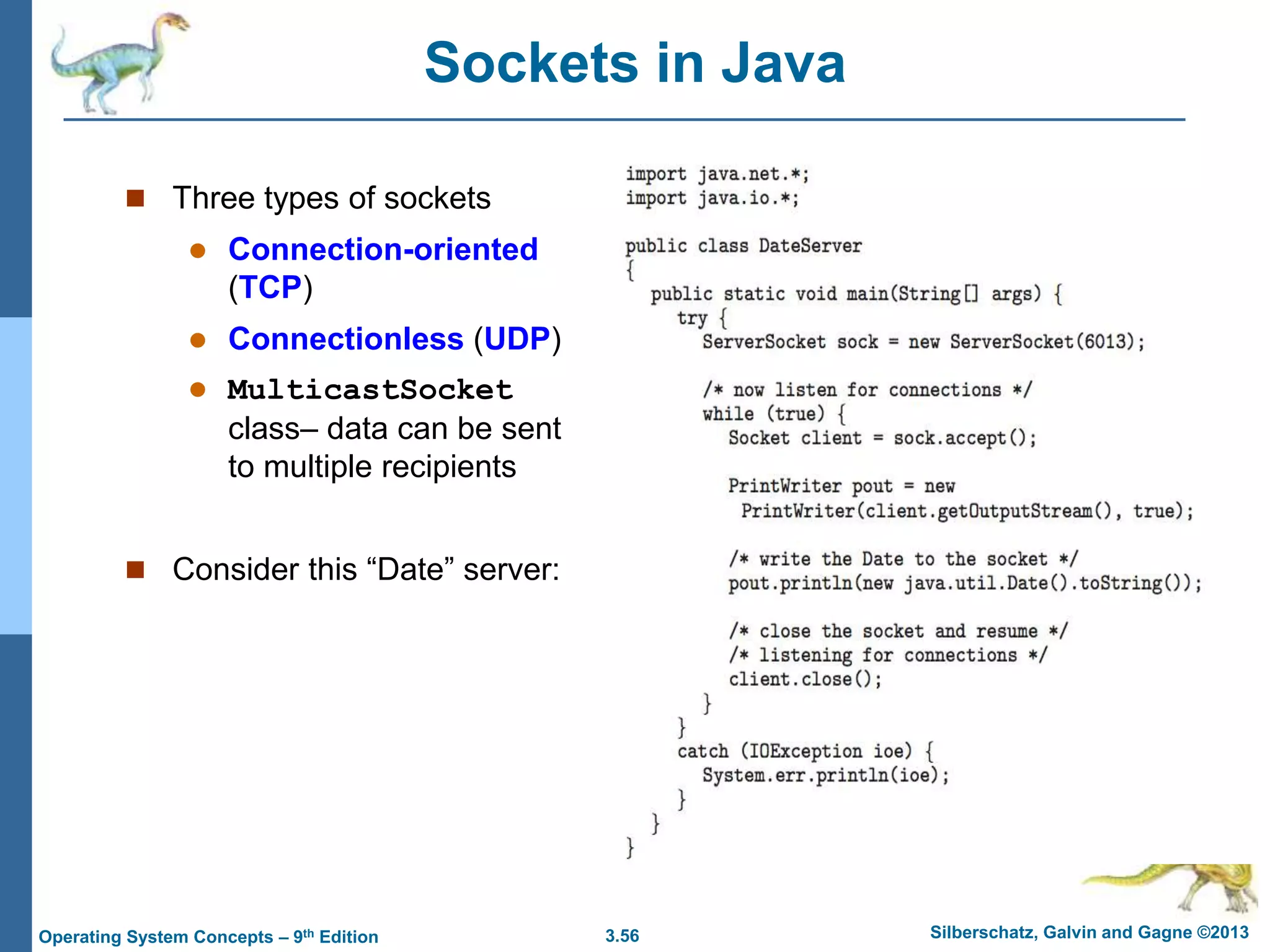

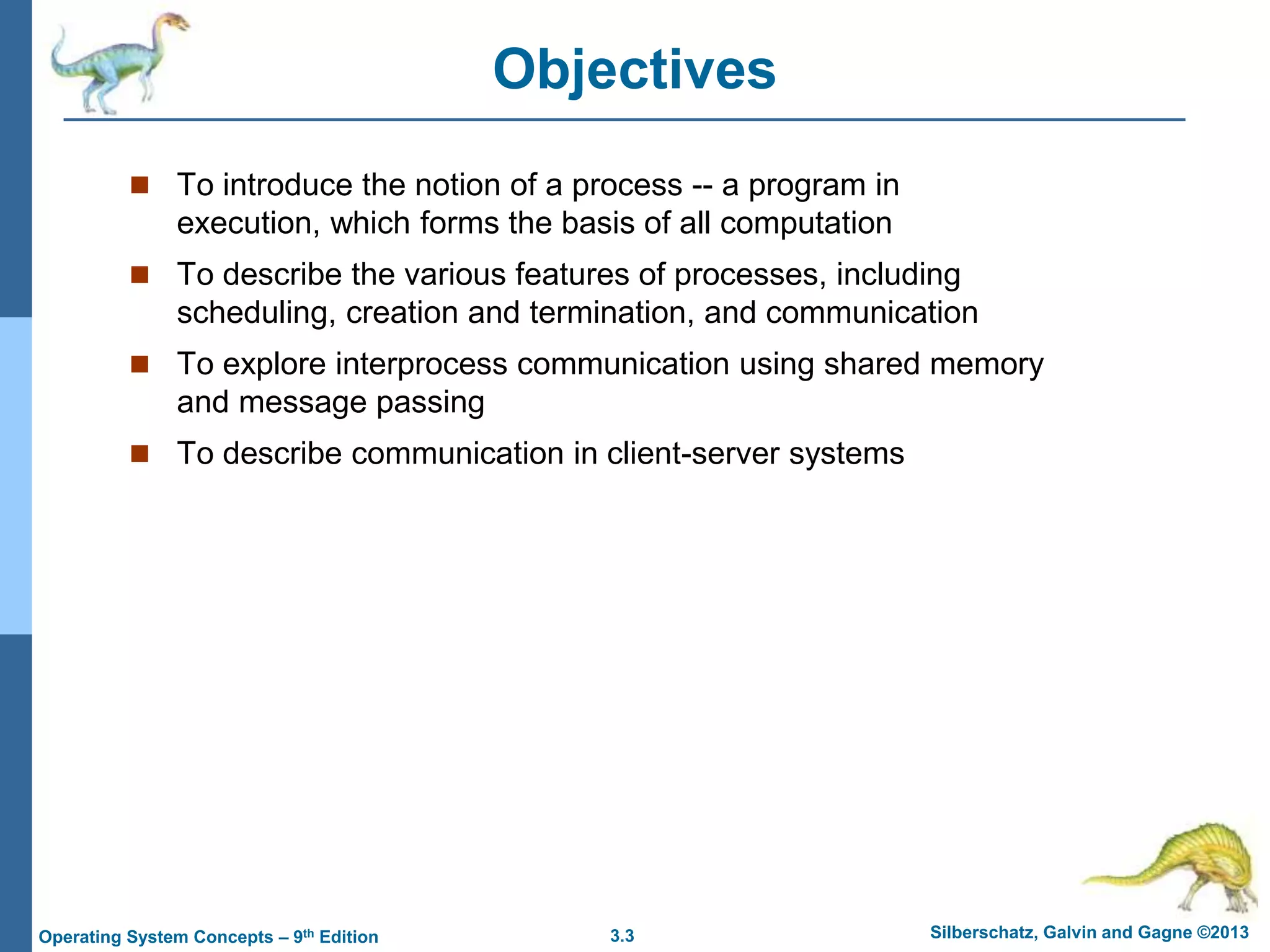

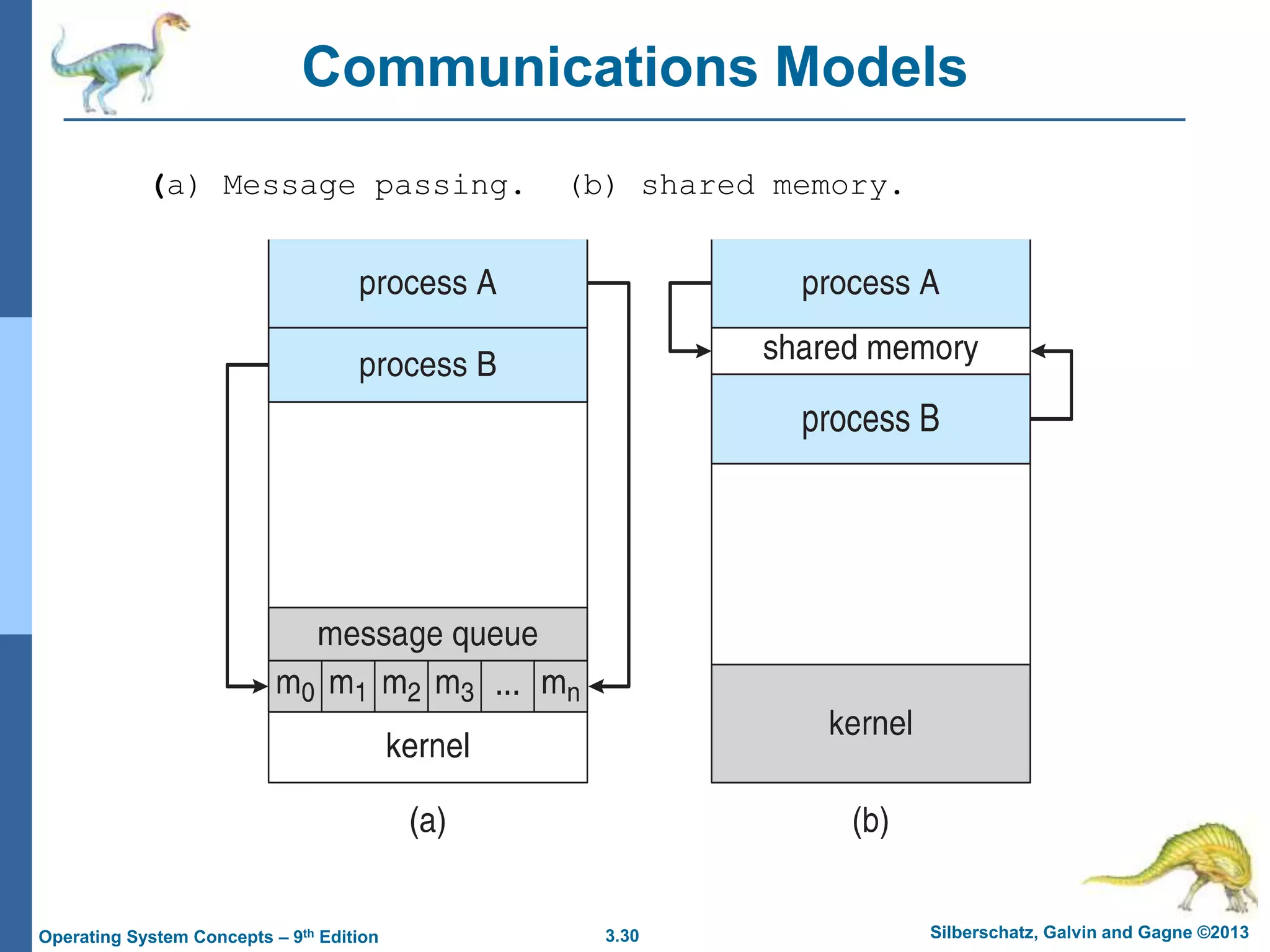

Bounded-Buffer – Shared-Memory Solution

Shared data

#define BUFFER_SIZE 10

typedef struct {

. . .

} item;

item buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

int in = 0;

int out = 0;

Solution is correct, but can only use BUFFER_SIZE-1 elements](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processesinoperatingsystem-211210050503/75/Operating-System-33-2048.jpg)

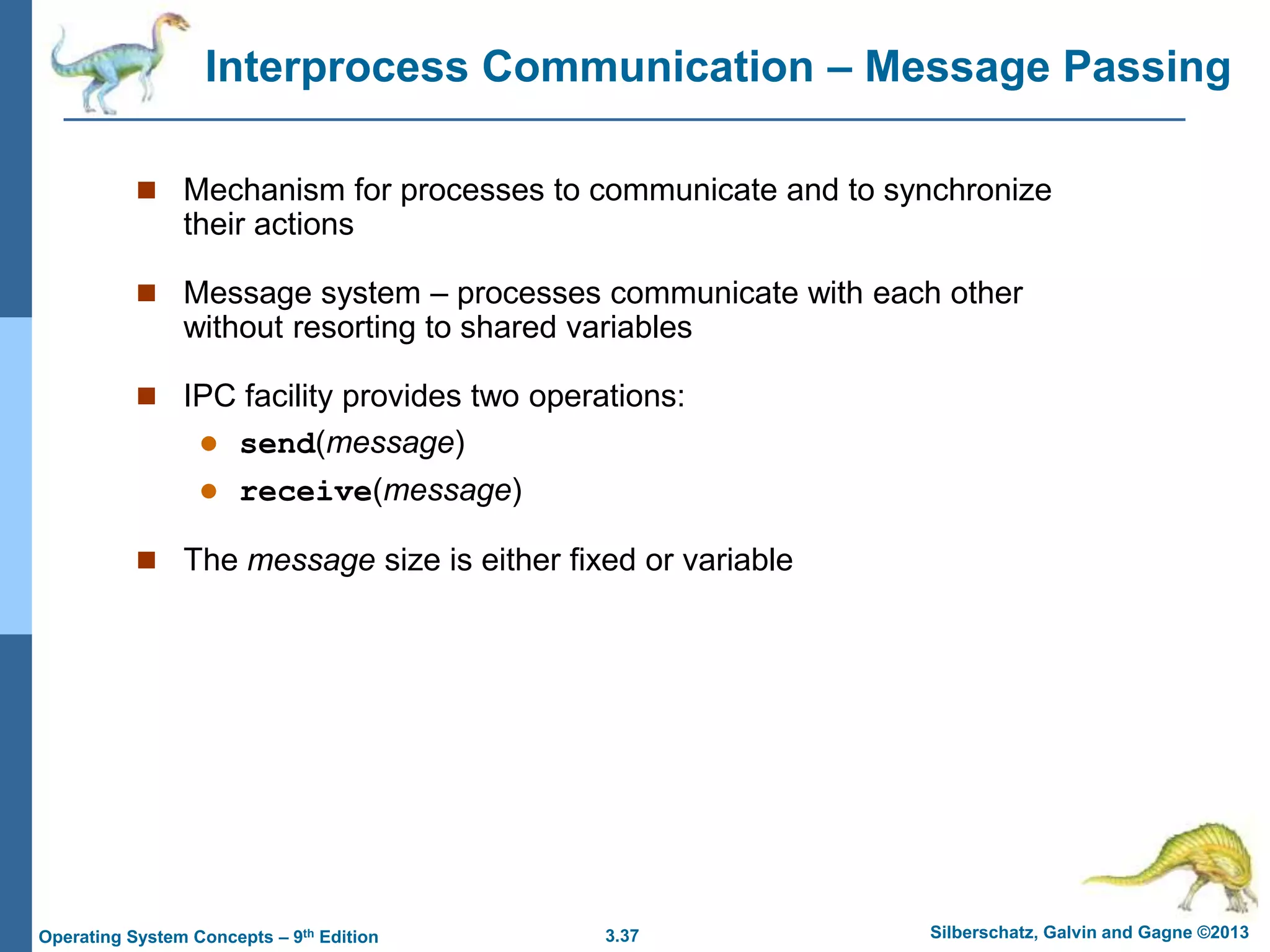

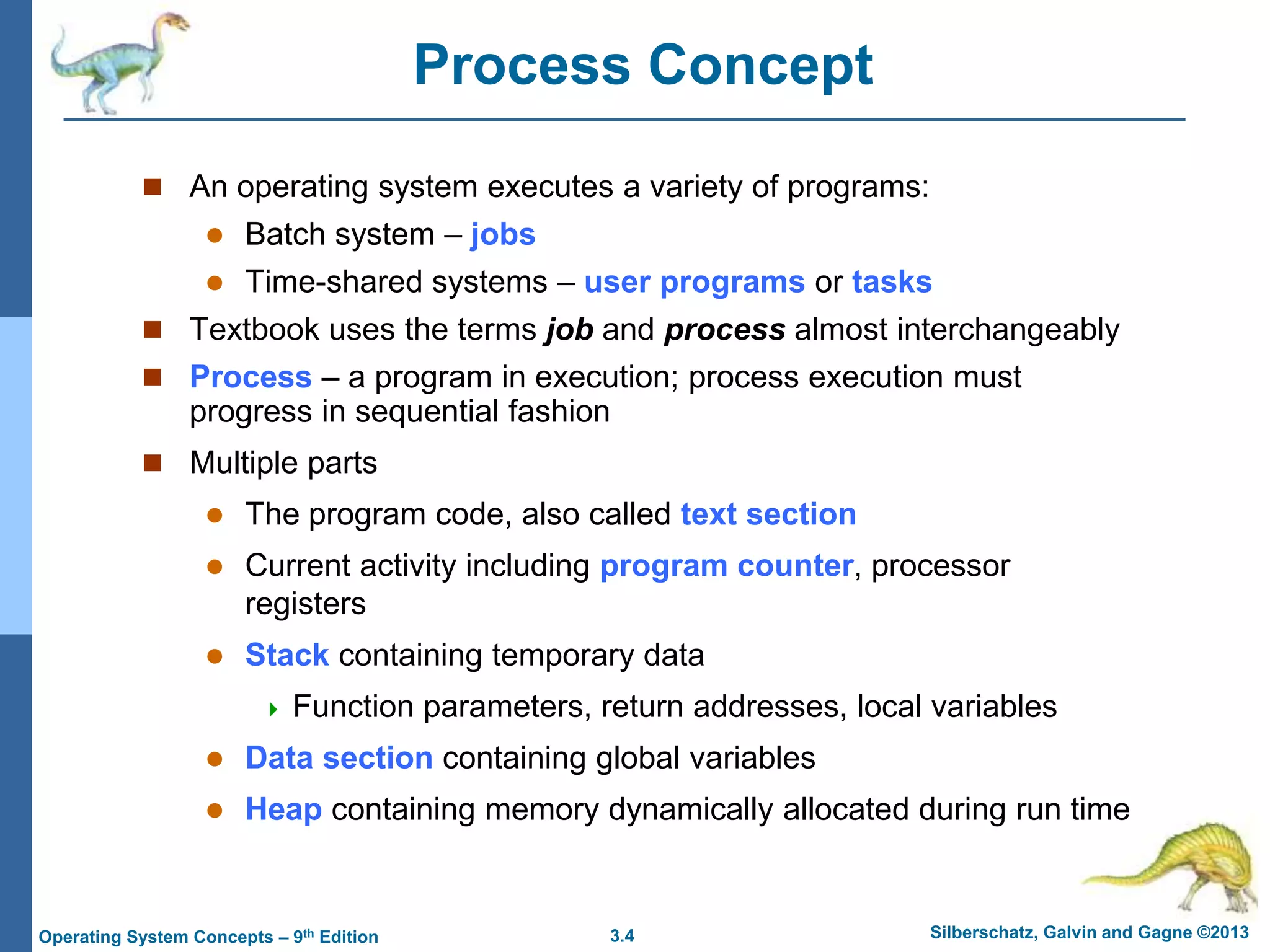

![3.34 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

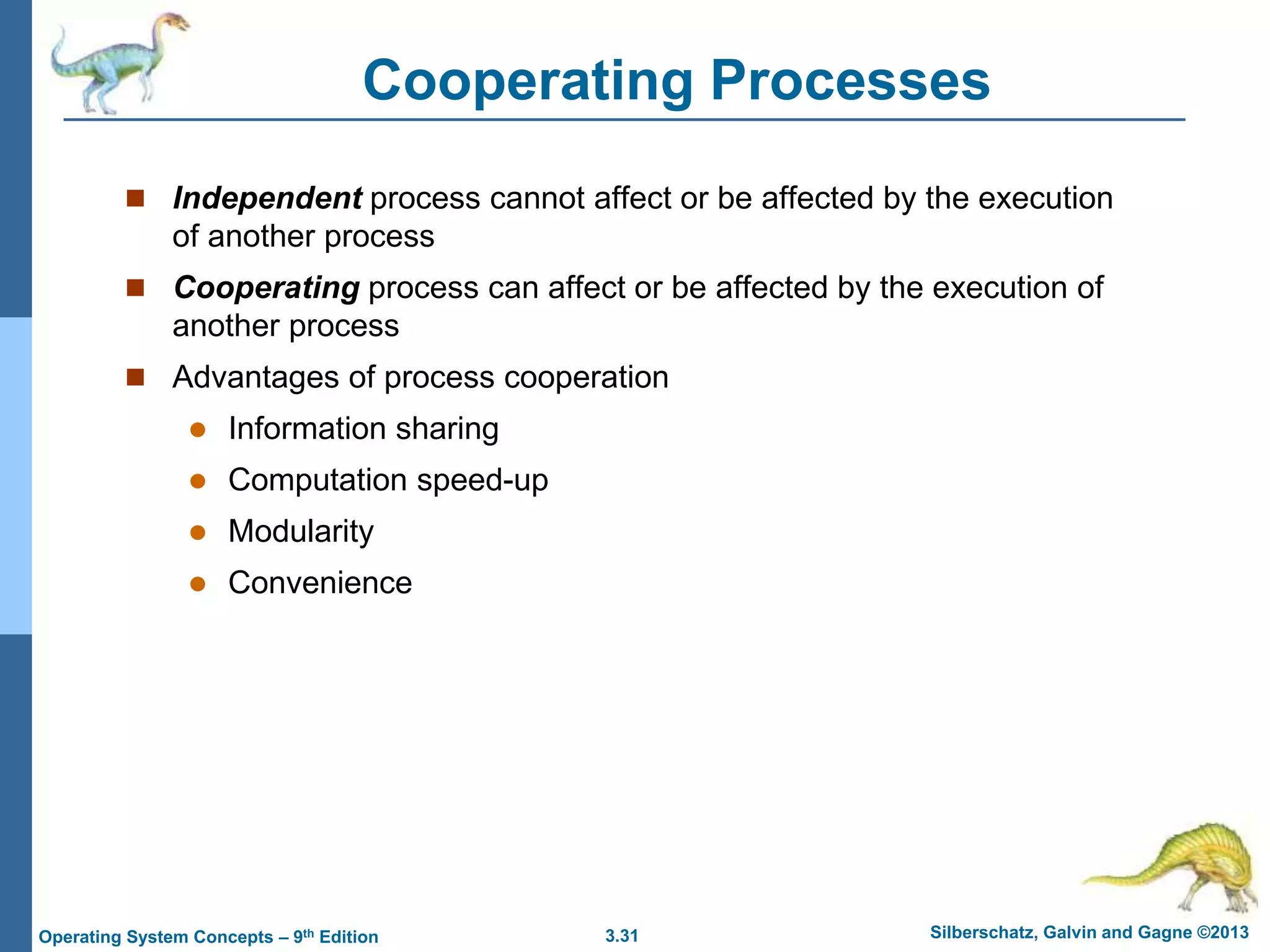

Bounded-Buffer – Producer

item next_produced;

while (true) {

/* produce an item in next produced */

while (((in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE) == out)

; /* do nothing */

buffer[in] = next_produced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processesinoperatingsystem-211210050503/75/Operating-System-34-2048.jpg)

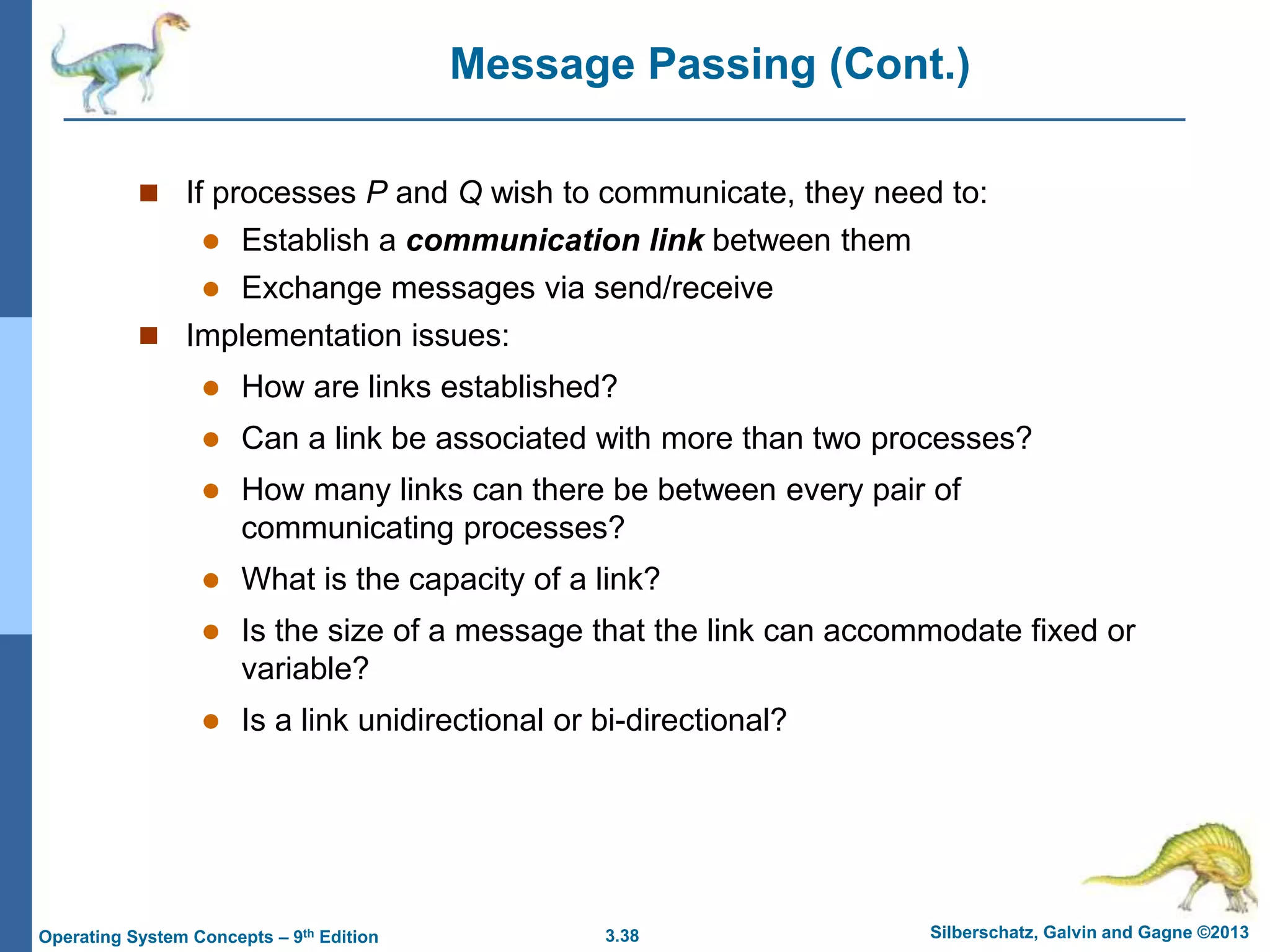

![3.35 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

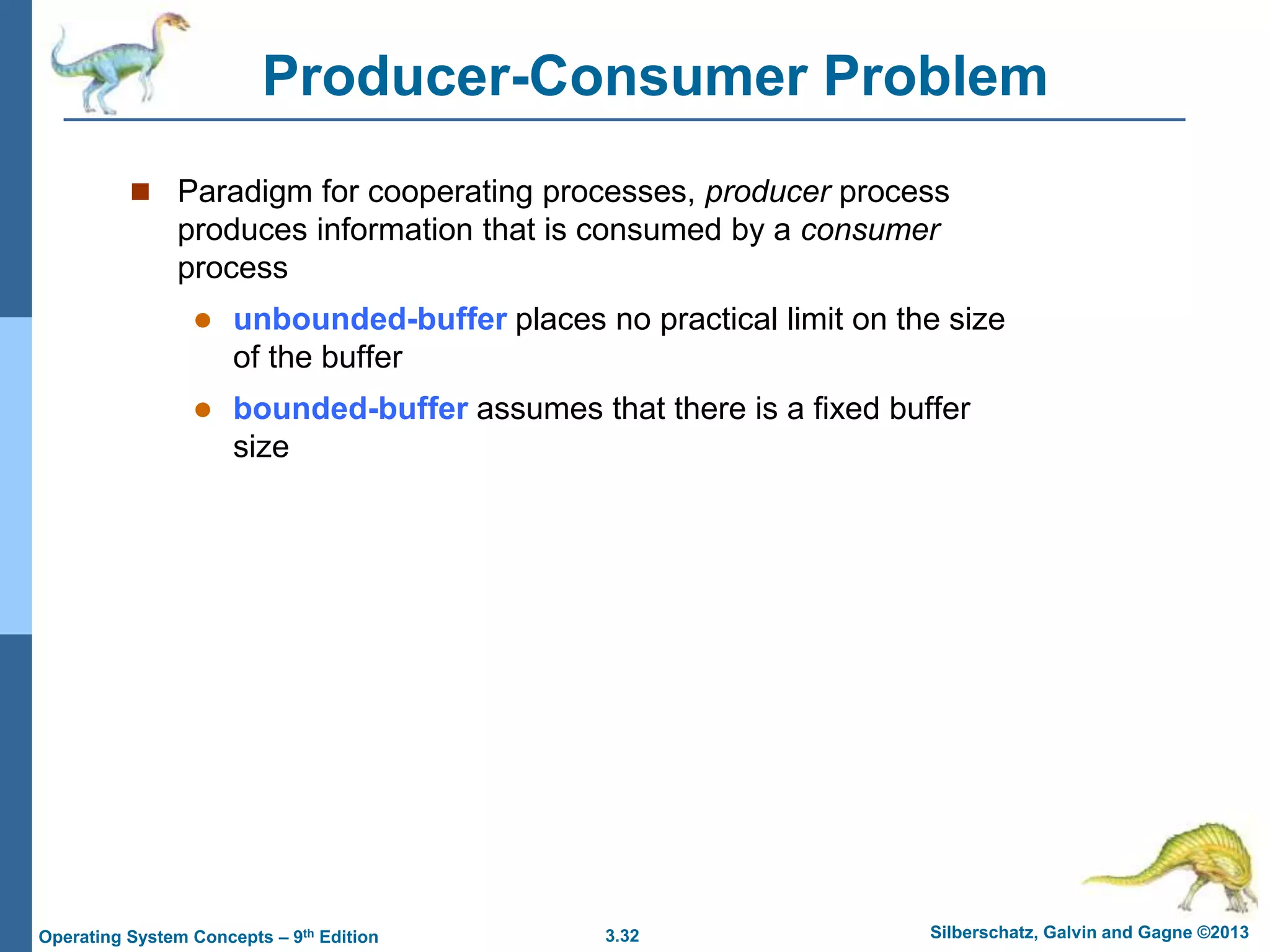

Bounded Buffer – Consumer

item next_consumed;

while (true) {

while (in == out)

; /* do nothing */

next_consumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

/* consume the item in next consumed */

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processesinoperatingsystem-211210050503/75/Operating-System-35-2048.jpg)