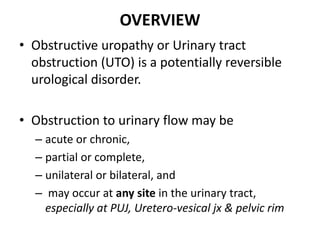

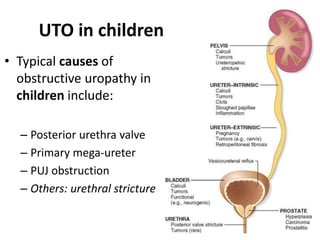

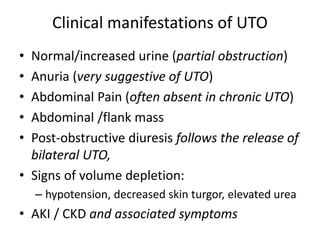

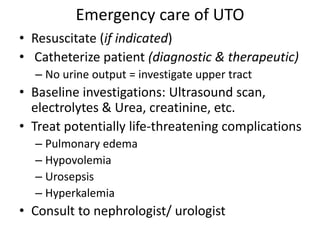

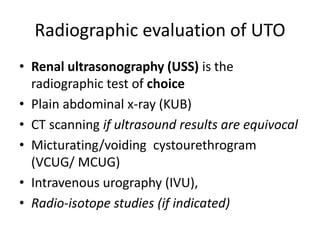

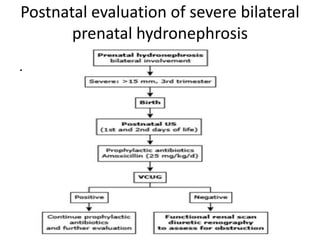

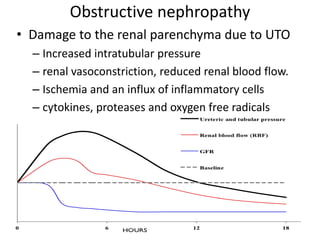

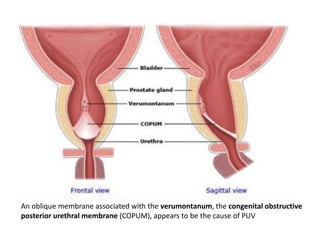

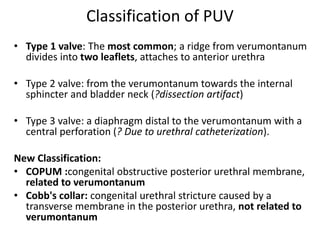

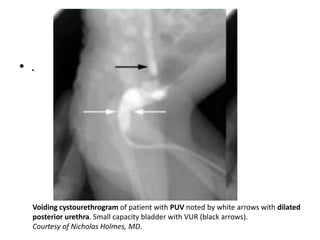

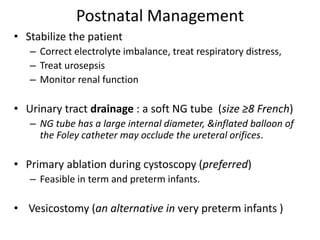

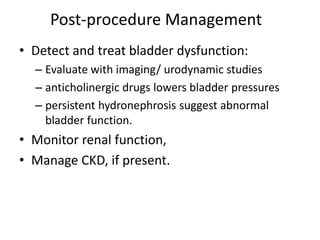

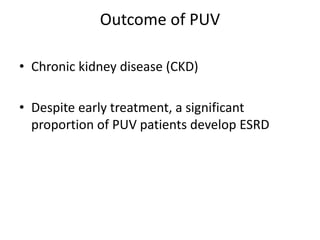

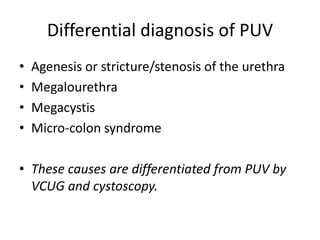

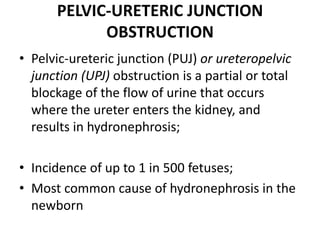

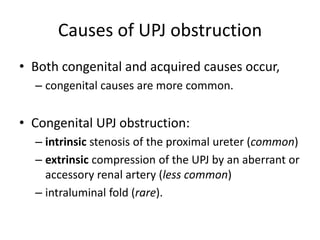

Obstructive uropathy (UTP) in children can arise from various causes, presenting either acutely or chronically and necessitating careful diagnosis and management. Key clinical features include renal dysfunction, abdominal pain, and urinary flow issues, with posterior urethral valves being a common cause. Effective management involves both emergency interventions and long-term strategies to prevent kidney failure and ensure the child's well-being.