- Malnutrition is common in 30-60% of hospitalized patients, especially those with prolonged stays or postoperative complications, and increases the risk of further complications and death.

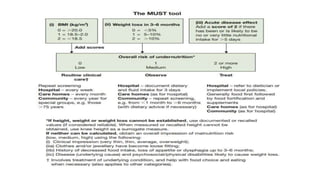

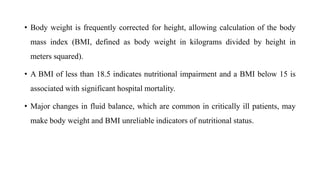

- Nutritional assessment involves clinical evaluation of weight loss, lab tests like albumin and lymphocyte count, and anthropometric measurements like BMI, though these have limitations in critically ill patients.

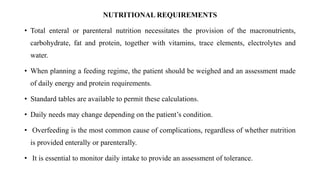

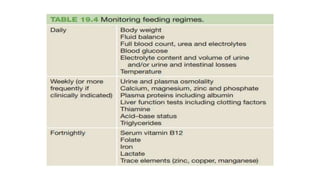

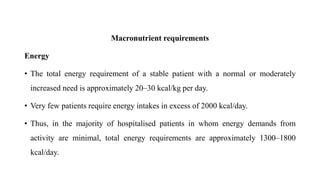

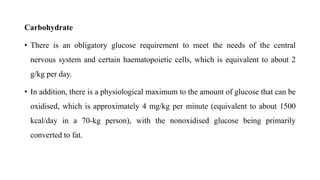

- Nutritional support aims to meet caloric and protein needs through enteral or parenteral nutrition while avoiding overfeeding, with requirements varying based on patient condition and stress level.