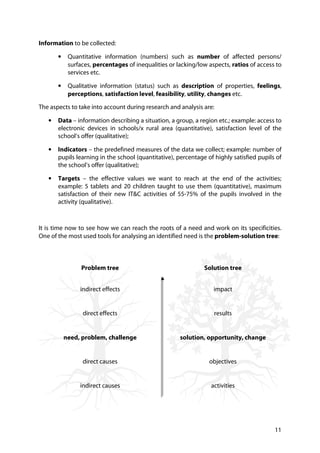

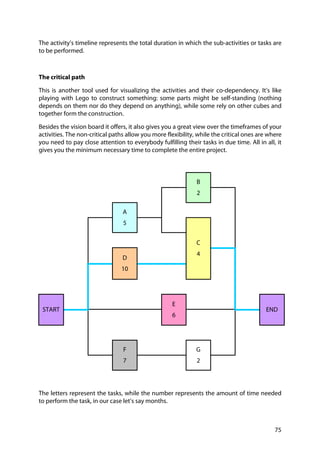

The document outlines a manual created for the 'soundbeatstime' project to assist organizations, particularly beginners, in community engagement through project management. It emphasizes the importance of understanding project cycles, needs analysis, and effective preparation for securing EU funds within the context of youth sector projects. The guide shares practical experiences and resources to help avoid common mistakes in project writing and management.