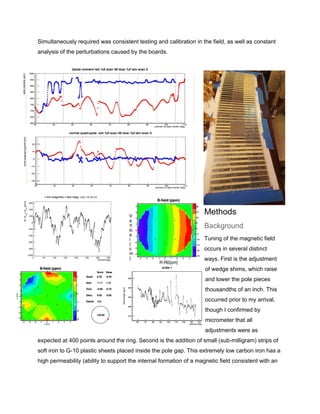

The Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab aims to precisely measure the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon to test predictions of the Standard Model. Current efforts involve shaping the magnetic field in the storage ring to reduce uncertainties. Laminating over 9,000 small iron foils around the ring poles has improved field consistency from 200 ppm to under 25 ppm azimuthally. Further reductions to below 0.5 ppm are expected to achieve the experiment's goal of limiting systematic uncertainties to 140 ppb.