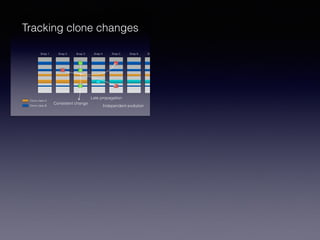

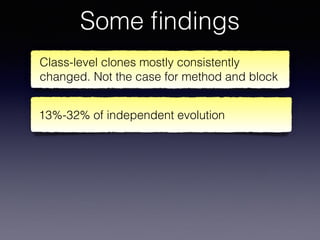

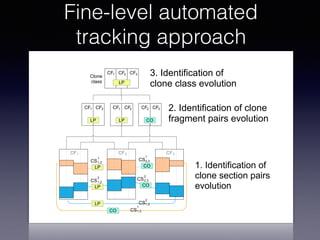

This document presents an empirical study on the maintenance of software code clones from 2007 to 2017, challenging the perception that cloning is a risky practice. It finds that most cloned code is consistently maintained during bug fixing and evolution, supporting the idea that code clones can be beneficial. The study utilizes clone detection and co-change analysis to examine how clones evolve in software repositories.

![We got the Paper!

How Clones are Maintained: An Empirical Study

Lerina Aversano, Luigi Cerulo, Massimiliano Di Penta

RCOST — Research Centre on Software Technology

Department of Engineering - University of Sannio

Viale Traiano - 82100 Benevento, Italy

{aversano, lcerulo, dipenta}@unisannio.it

Abstract

Despite the conventional wisdom concerning the risks

related to the use of source code cloning as a software de-

velopment strategy, several studies appeared in literature

indicated that this is not true. In most cases clones are prop-

erly maintained and, when this does not happen, is because

cloned code evolves independently.

Stemming from previous works, this paper combines

clone detection and co–change analysis to investigate how

clones are maintained when an evolution activity or a bug

fixing impact a source code fragment belonging to a clone

class. The two case studies reported confirm that, either for

bug fixing or for evolution purposes, most of the cloned code

is consistently maintained during the same co–change or

during temporally close co–changes.

Keywords: Clone detection, software evolution, mining

software repositories

1. Introduction

Several recent studies contradict the common wisdom

that cloning constitutes a risky practice: as found by Kim et

al. [16]. As shown in a paper by Kasper and Godfrey [15],

source code clones are not necessarily to be considered

harmful but, many times, as a way to develop software cre-

ating, for example, new features starting for existing, simi-

lar ones. Whilst this creates duplications, it also permits the

use of stable, already tested and used code.

This paper aims to report results from an empiri-

cal study aiming to investigate how clones, detected in a

given release of a software system, are affected by mainte-

nance intervention. The analysis is performed by intersect-

ing cloned classes with data from Modification Transactions

(MTs) mined from source code repositories. A MT iden-

tifies groups of source code lines co-changed in the same

time window. The work is built upon the idea of clone pat-

terns described by Kasper and Godfrey and of clone

evolution patterns described by Kim et al., and investi-

gates whether clones (i) are updated consistently during

the same MT or near MTs, confirming the correlation be-

tween MTs and clones, as experienced by Geiger et al.

[10]; (ii) evolve independently; or (iii) are subject to up-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-46-320.jpg)

![Submit where?

How Clones are Maintained: An Empirical Study

Lerina Aversano, Luigi Cerulo, Massimiliano Di Penta

RCOST — Research Centre on Software Technology

Department of Engineering - University of Sannio

Viale Traiano - 82100 Benevento, Italy

{aversano, lcerulo, dipenta}@unisannio.it

Abstract

Despite the conventional wisdom concerning the risks

related to the use of source code cloning as a software de-

velopment strategy, several studies appeared in literature

indicated that this is not true. In most cases clones are prop-

erly maintained and, when this does not happen, is because

cloned code evolves independently.

Stemming from previous works, this paper combines

clone detection and co–change analysis to investigate how

clones are maintained when an evolution activity or a bug

fixing impact a source code fragment belonging to a clone

class. The two case studies reported confirm that, either for

bug fixing or for evolution purposes, most of the cloned code

is consistently maintained during the same co–change or

during temporally close co–changes.

Keywords: Clone detection, software evolution, mining

software repositories

1. Introduction

Several recent studies contradict the common wisdom

that cloning constitutes a risky practice: as found by Kim et

al. [16]. As shown in a paper by Kasper and Godfrey [15],

source code clones are not necessarily to be considered

harmful but, many times, as a way to develop software cre-

ating, for example, new features starting for existing, simi-

lar ones. Whilst this creates duplications, it also permits the

use of stable, already tested and used code.

This paper aims to report results from an empiri-

cal study aiming to investigate how clones, detected in a

given release of a software system, are affected by mainte-

nance intervention. The analysis is performed by intersect-

ing cloned classes with data from Modification Transactions

(MTs) mined from source code repositories. A MT iden-

tifies groups of source code lines co-changed in the same

time window. The work is built upon the idea of clone pat-

terns described by Kasper and Godfrey and of clone

evolution patterns described by Kim et al., and investi-

gates whether clones (i) are updated consistently during

the same MT or near MTs, confirming the correlation be-

tween MTs and clones, as experienced by Geiger et al.

[10]; (ii) evolve independently; or (iii) are subject to up-

WCRE?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-47-320.jpg)

![Submit where?

How Clones are Maintained: An Empirical Study

Lerina Aversano, Luigi Cerulo, Massimiliano Di Penta

RCOST — Research Centre on Software Technology

Department of Engineering - University of Sannio

Viale Traiano - 82100 Benevento, Italy

{aversano, lcerulo, dipenta}@unisannio.it

Abstract

Despite the conventional wisdom concerning the risks

related to the use of source code cloning as a software de-

velopment strategy, several studies appeared in literature

indicated that this is not true. In most cases clones are prop-

erly maintained and, when this does not happen, is because

cloned code evolves independently.

Stemming from previous works, this paper combines

clone detection and co–change analysis to investigate how

clones are maintained when an evolution activity or a bug

fixing impact a source code fragment belonging to a clone

class. The two case studies reported confirm that, either for

bug fixing or for evolution purposes, most of the cloned code

is consistently maintained during the same co–change or

during temporally close co–changes.

Keywords: Clone detection, software evolution, mining

software repositories

1. Introduction

Several recent studies contradict the common wisdom

that cloning constitutes a risky practice: as found by Kim et

al. [16]. As shown in a paper by Kasper and Godfrey [15],

source code clones are not necessarily to be considered

harmful but, many times, as a way to develop software cre-

ating, for example, new features starting for existing, simi-

lar ones. Whilst this creates duplications, it also permits the

use of stable, already tested and used code.

This paper aims to report results from an empiri-

cal study aiming to investigate how clones, detected in a

given release of a software system, are affected by mainte-

nance intervention. The analysis is performed by intersect-

ing cloned classes with data from Modification Transactions

(MTs) mined from source code repositories. A MT iden-

tifies groups of source code lines co-changed in the same

time window. The work is built upon the idea of clone pat-

terns described by Kasper and Godfrey and of clone

evolution patterns described by Kim et al., and investi-

gates whether clones (i) are updated consistently during

the same MT or near MTs, confirming the correlation be-

tween MTs and clones, as experienced by Geiger et al.

[10]; (ii) evolve independently; or (iii) are subject to up-

Sorry! I’m WCRE

PC co-chair](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-48-320.jpg)

![Submit where?

How Clones are Maintained: An Empirical Study

Lerina Aversano, Luigi Cerulo, Massimiliano Di Penta

RCOST — Research Centre on Software Technology

Department of Engineering - University of Sannio

Viale Traiano - 82100 Benevento, Italy

{aversano, lcerulo, dipenta}@unisannio.it

Abstract

Despite the conventional wisdom concerning the risks

related to the use of source code cloning as a software de-

velopment strategy, several studies appeared in literature

indicated that this is not true. In most cases clones are prop-

erly maintained and, when this does not happen, is because

cloned code evolves independently.

Stemming from previous works, this paper combines

clone detection and co–change analysis to investigate how

clones are maintained when an evolution activity or a bug

fixing impact a source code fragment belonging to a clone

class. The two case studies reported confirm that, either for

bug fixing or for evolution purposes, most of the cloned code

is consistently maintained during the same co–change or

during temporally close co–changes.

Keywords: Clone detection, software evolution, mining

software repositories

1. Introduction

Several recent studies contradict the common wisdom

that cloning constitutes a risky practice: as found by Kim et

al. [16]. As shown in a paper by Kasper and Godfrey [15],

source code clones are not necessarily to be considered

harmful but, many times, as a way to develop software cre-

ating, for example, new features starting for existing, simi-

lar ones. Whilst this creates duplications, it also permits the

use of stable, already tested and used code.

This paper aims to report results from an empiri-

cal study aiming to investigate how clones, detected in a

given release of a software system, are affected by mainte-

nance intervention. The analysis is performed by intersect-

ing cloned classes with data from Modification Transactions

(MTs) mined from source code repositories. A MT iden-

tifies groups of source code lines co-changed in the same

time window. The work is built upon the idea of clone pat-

terns described by Kasper and Godfrey and of clone

evolution patterns described by Kim et al., and investi-

gates whether clones (i) are updated consistently during

the same MT or near MTs, confirming the correlation be-

tween MTs and clones, as experienced by Geiger et al.

[10]; (ii) evolve independently; or (iii) are subject to up-

Lets try with

CSMR, it is in

Amsterdam!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-49-320.jpg)

![We got

accepted!

Amsterdam we’re coming

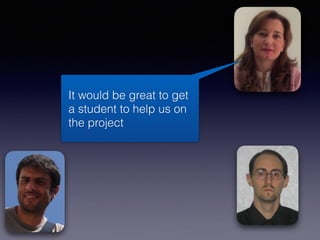

From: Massimiliano Di Penta <dipenta@unisannio.it>

Subject: [Fwd: CSMR 2007 Notification]

Date: 30 Nov 2006 15:28:59 CET

To: Lerina Aversano <aversano@unisannio.it>, "Luigi Cerulo"

<lcerulo@unisannio.it>

great...ecco le revisioni ... non so in effetti tra il primo e il terzo quale e' il piu'

negativo (magari il primo)

La critica del primo e' tutto sommato condivisibile, nel senso che considera il

lavoro buono anche se molte cose si sapevano gia' (come del resto nel paper

di Godfrey che nonostante una A aveva ricevuto qualche commento simile a

WCRE) e questo e' yet another study.. (magari con qualche livello di dettaglio

in piu')... da spiegare meglio nel camera ready copy

…

Guardate qui: se la gente dovesse seguire questa regola non si

pubblicherebbe mai neanche su TSE ... !!

General advice: Please submit your paper to a workshop to discuss the setup

of your experiments. A submission for a conference should analyse more (>=

10) throughly selected software systems. As you suggest, your clone

detection tool is very conservative, and you should perform the analyses

with several different tools. Only then, your claim would be sufficiently

supported.

….

Ciao

Max

Amsterdam](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-51-320.jpg)

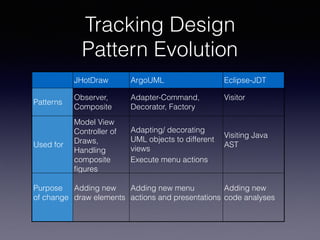

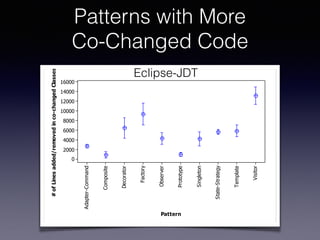

![Tracking Design Patterns

An Empirical Study on the Evolution of Design Patterns

Lerina Aversano, Gerardo Canfora, Luigi Cerulo,

Concettina Del Grosso, Massimiliano Di Penta

RCOST – Research Centre on Software Technology, University of Sannio

Via Traiano, 82100 Benevento, Italy

aversano@unisannio,it, canfora@unisannio.it, lcerulo@unisannio.it,

tina.delgrosso@unisannio.it, dipenta@unisannio.it

ABSTRACT

Design patterns are solutions to recurring design problems,

conceived to increase benefits in terms of reuse, code quality

and, above all, maintainability and resilience to changes.

This paper presents results from an empirical study aimed

at understanding the evolution of design patterns in three

open source systems, namely JHotDraw, ArgoUML, and

Eclipse-JDT. Specifically, the study analyzes how frequently

patterns are modified, to what changes they undergo and

what classes co-change with the patterns. Results show

how patterns more suited to support the application pur-

pose tend to change more frequently, and that different kind

of changes have a different impact on co-changed classes

and a different capability of making the system resilient to

changes.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

D.2.2 [Software Engineering]: Design Tools And Tech-

niques—Object-oriented design methods

General Terms

Design, Experimentation, Measurement

Keywords

Design patterns, Software Evolution, Mining Software Repo-

sitories, Empirical Software Engineering

1. INTRODUCTION

some aspect of system structure vary independently of other

aspects, thereby making a system more robust to a particu-

lar kind of change”. Advantages of design patterns include

decoupling a request from specific operations (Chain of Re-

sponsibility and Command), making a system independent

from software and hardware platforms (Abstract Factory

and Bridge), independent from algorithmic solutions (Itera-

tor, Strategy, Visitor), or avoid modifying implementations

(Adapter, Decorator, Visitor). Further discussion on design

pattern advantages, and extensive pattern catalogues can be

found in books such as [11] or [9].

While many benefits related to the use of design patterns

have been stated, a little has been done to empirically in-

vestigate pattern change proneness [3] or whether there is a

relationships between the presence of defects in the source

code and the use of design patterns [24]. In particular, there

is lack of empirical studies aimed at analyzing what kind of

changes each type of pattern undergoes during software evo-

lution, and whether such a change can be related to changes

contextually made on other classes not belonging to the pat-

tern. The availability of source repositories for many object-

oriented open source systems realized making use of design

patterns, of techniques for identifying change sets [10] —

i.e., sets of artifacts changed together by the same author

— from source code repositories, and of design pattern de-

tection techniques and tools [1, 8, 15, 19, 23], triggers op-

portunities for this kind of studies.

This paper reports and discusses results from an empir-

ical study aimed at analyzing how design patterns change

during a software system lifetime, and to what extent such

changes cause modifications to other classes not part of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-81-320.jpg)

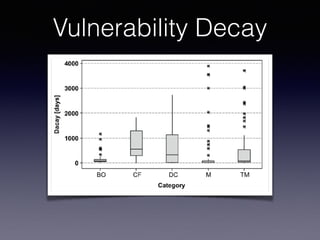

![Tracking Vulnerabilities

The life and death of statically detected vulnerabilities: An empirical study

Massimiliano Di Penta a,*, Luigi Cerulo b

, Lerina Aversano a

a

Dept. of Engineering, University of Sannio, Via Traiano, 82100 Benevento, Italy

b

Dept. of Biological and Environmental Studies, University of Sannio, Via Port’Arsa, 11 – 82100 Benevento, Italy

a r t i c l e i n f o

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Software vulnerabilities

Mining software repositories

Empirical study

a b s t r a c t

Vulnerable statements constitute a major problem for developers and maintainers of networking sys-

tems. Their presence can ease the success of security attacks, aimed at gaining unauthorized access to

data and functionality, or at causing system crashes and data loss. Examples of attacks caused by source

code vulnerabilities are buffer overflows, command injections, and cross-site scripting.

This paper reports on an empirical study, conducted across three networking systems, aimed at observ-

ing the evolution and decay of vulnerabilities detected by three freely available static analysis tools. In

particular, the study compares the decay of different kinds of vulnerabilities, characterizes the decay like-

lihood through probability density functions, and reports a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the

reasons for vulnerability removals. The study is performed by using a framework that traces the evolution

of source code fragments across subsequent commits.

Ó 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Vulnerable instructions are, very often, the cause of serious

problems such as security attacks, system failures or crashes. In

his Ph.D. thesis [1] Krsul defined a software vulnerability as ‘‘an in-

stance of an error in the specification, development, or configuration of

software such that its execution can violate the security policy”. For

business-critical systems, the presence of vulnerable instructions

in the source code is often the cause of security attacks or, in other

cases, of system failures or crashes. The problem is particularly rel-

Detecting the presence of such instructions is therefore crucial

to ensure high security and reliability. Indeed, security advisories

are regularly published – see for example those of Linux distribu-

tions3

Microsoft,4

those published by CERT, or by securityfocus.5

These advisories, however, are posted when a problem already

occurred in the application, a problem that was very often caused

by the introduction in the source code of vulnerable statements. This

highlights the needs to identify potential problems when they are

introduced, and to keep track of them during the software system

lifetime, as it is done, for example for source code clones [2].

Information and Software Technology xxx (2009) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Information and Software Technology

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/infsof

ARTICLE IN PRESS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-84-320.jpg)

![Migration From

Third-Party Code

commit a9474917099e007c0f51d5474394b5890111614f

Author: Sean Hefty <sean.hefty@intel.com>

Date: Mon Jul 14 23:48:43 2008 -0700

RDMA: Fix license text

The license text for several files references a third software license

that was inadvertently copied in. Update the license to what was

intended. This update was based on a request from HP. [..]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-91-320.jpg)

![Blame-based tracking

Distinguishing Copies from Originals in Software Clones

Jens Krinke, Nicolas Gold, Yue Jia

King’s College London

Centre for Research on Evolution, Search and

Testing (CREST)

{jens.krinke,nicolas.gold,yue.jia}@kcl.ac.uk

David Binkley

Loyola University Maryland

Baltimore, MD, USA

binkley@cs.loyola.edu

ABSTRACT

Cloning is widespread in today’s systems where automated assis-

tance is required to locate cloned code. Although the evolution of

clones has been studied for many years, no attempt has been made

so far to automatically distinguish the original source code leading

to cloned copies. This paper presents an approach to classify the

clones of a clone pair based on the version information available

in version control systems. This automatic classification attempts

to distinguish the original from the copy. It allows for the fact that

the clones may be modified and thus consist of lines coming from

different versions. An evaluation, based on two case studies, shows

that when comments are ignored and a small tolerance is accepted,

for the majority of clone pairs the proposed approach can automat-

ically distinguish between the original and the copy.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

D.2.9 [Software Engineering]: Management—Software config-

uration management; D.2.13 [Software Engineering]: Reusable

Software—Reusable libraries

General Terms

Algorithms

Keywords

Clone detection, mining software archives, software evolution

1. INTRODUCTION

The duplication of code is a common practice to make software

existing code. However, such practices can complicate software

maintenance so it has been suggested that too much cloned code is

a risk, albeit the practice itself is not generally harmful [16]. Be-

cause of these problems, many approaches to detecting cloned code

have been developed [2, 3, 8, 15, 18–20, 24, 26]. While methods to

identify clones automatically and efficiently are to some extent un-

derstood, it is still disputable whether the presence of clones is a

risk. To better understand why and how code is cloned, recent em-

pirical studies of cloned code have focused mainly on examining

the evolution of clones, such as whether cloned code is more stable

or changed consistently [1,10,12,17,21,22,27].

A lot of research has been done on finding and identifying soft-

ware clones, but without additional information it is impossible to

distinguish the original from the copy. Most of the above men-

tioned previous empirical studies used version control systems to

extract limited information about the discovered clones; for exam-

ple, when a clone appears in some previous version. However, so

far there has been no general approach proposed to distinguish orig-

inals from copies except for a study done by German et al. [11] who

tracked when clones appeared in the version history to identify the

clone of a pair that appeared first. This paper presents an approach

that uses line-by-line version information available from version

control systems to distinguish the original from the copied code

clone in a clone pair.

Most version control systems have a ‘blame’ command which

shows author and version information for each line in a file. This

information, which includes the version when the line was added or

last modified, can be used as a line age: if all lines in one clone have

older versions than the lines in the other clone of a clone pair, then

the clone with the older lines may be the original and the other may

be the copy (assuming that the clone with the oldest lines existed

Cloning and Copying between GNOME Projects

Jens Krinke, Nicolas Gold, Yue Jia

King’s College London,

Centre for Research on Evolution, Search and Testing (CREST)

{jens.krinke,nicolas.gold,yue.jia}@kcl.ac.uk

David Binkley

Loyola University Maryland,

Baltimore, MD, USA

binkley@cs.loyola.edu

Abstract—This paper presents an approach to automatically

distinguish the copied clone from the original in a pair of clones.

It matches the line-by-line version information of a clone to the

pair’s other clone. A case study on the GNOME Desktop Suite

revealed a complex flow of reused code between the different

subprojects. In particular, it showed that the majority of larger

clones (with a minimal size of 28 lines or higher) exist between

the subprojects and more than 60% of the clone pairs can be

automatically separated into original and copy.

I. INTRODUCTION

The duplication of code is a common practice to make

software development faster, to enable “experimental” devel-

is most likely the original and the other the copy. However,

usually, it is not that simple because the original and the copy

may have been modified in turn after the copy was created.

This paper makes the following contributions:

• It extends previous work [19] to automatically distinguish

between copy and original by allowing the clones of a

clone pair to be in different systems.

• A case study on the GNOME Desktop Suite subprojects

shows that the majority of larger clones (with a minimal

size of 28 lines or higher) exist between the subprojects

and more than 60% of the clone pairs can be automat-

ically separated automatically into original and copied](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-92-320.jpg)

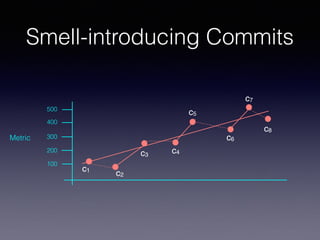

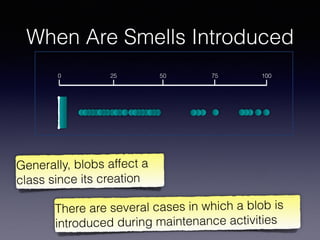

![Smell Evolution

When and Why Your Code Starts to Smell Bad

(and Whether the Smells Go Away)

Michele Tufano1, Fabio Palomba2, Gabriele Bavota3

Rocco Oliveto4, Massimiliano Di Penta5, Andrea De Lucia2, Denys Poshyvanyk1

1The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA 2University of Salerno, Fisciano (SA), Italy,

3Universit`a della Svizzera italiana (USI), Switzerland, 4University of Molise, Pesche (IS), Italy,

5University of Sannio, Benevento (BN), Italy

mtufano@email.wm.edu, fpalomba@unisa.it, gabriele.bavota@usi.ch

rocco.oliveto@unimol.it, dipenta@unisannio.it, adelucia@unisa.it, denys@cs.wm.edu

Abstract—Technical debt is a metaphor introduced by Cunningham to indicate “not quite right code which we postpone making it right”.

One noticeable symptom of technical debt is represented by code smells, defined as symptoms of poor design and implementation

choices. Previous studies showed the negative impact of code smells on the comprehensibility and maintainability of code. While

the repercussions of smells on code quality have been empirically assessed, there is still only anecdotal evidence on when and

why bad smells are introduced, what is their survivability, and how they are removed by developers. To empirically corroborate such

anecdotal evidence, we conducted a large empirical study over the change history of 200 open source projects. This study required the

development of a strategy to identify smell-introducing commits, the mining of over half a million of commits, and the manual analysis

and classification of over 10K of them. Our findings mostly contradict common wisdom, showing that most of the smell instances are

introduced when an artifact is created and not as a result of its evolution. At the same time, 80% of smells survive in the system. Also,

among the 20% of removed instances, only 9% are removed as a direct consequence of refactoring operations.

Index Terms—Code Smells, Empirical Study, Mining Software Repositories

F

1 INTRODUCTION

THE technical debt metaphor introduced by Cunning-

ham [23] explains well the trade-offs between deliv-

ering the most appropriate but still immature product,

removed [14]. This represents an obstacle for an effec-

tive and efficient management of technical debt. Also,

understanding the typical life-cycle of code smells and

the actions undertaken by developers to remove them

is of paramount importance in the conception of recom-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-93-320.jpg)

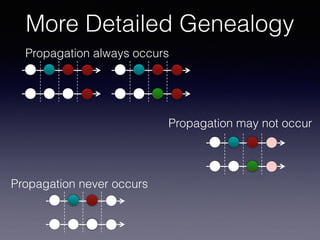

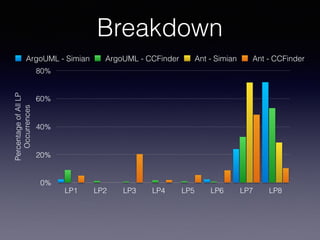

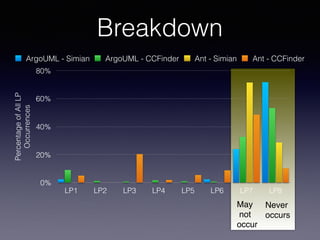

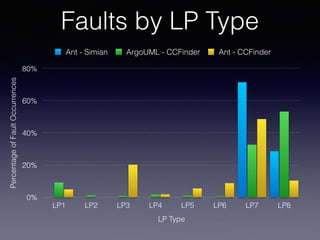

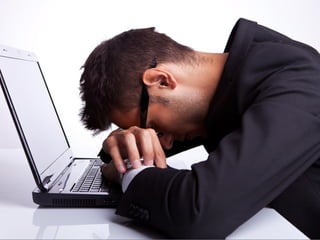

![Late Propagation in Software Clones

Liliane Barbour, Foutse Khomh, Ying Zou

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Queen’s University

Kingston, ON

{l.barbour, foutse.khomh, ying.zou}@queensu.ca

Abstract—Two similar code segments, or clones, form a clone

pair within a software system. The changes to the clones over

time create a clone evolution history. In this work we study

late propagation, a specific pattern of clone evolution. In late

propagation, one clone in the clone pair is modified, causing

the clone pair to become inconsistent. The code segments

are then re-synchronized in a later revision. Existing work

has established late propagation as a clone evolution pattern,

and suggests that the pattern is related to a high number

of faults. In this study we examine the characteristics of

late propagation in two long-lived software systems using the

Simian and CCFinder clone detection tools. We define 8 types

of late propagation and compare them to other forms of clone

evolution. Our results not only verify that late propagation

is more harmful to software systems, but also establish that

some specific cases of late propagations are more harmful than

others. Specifically, two cases are most risky: (1) when a clone

experiences inconsistent changes and then a re-synchronizing

change without any modification to the other clone in a

clone pair; and (2) when two clones undergo an inconsistent

modification followed by a consistent change that modifies both

the clones in a clone pair.

Keywords-clone genealogies; late propagation; fault-

proneness.

I. INTRODUCTION

A code segment is labeled as a code clone if it is identical

or highly similar to another code segment. Similar code

segments form a clone pair. Clone pairs can be introduced

into systems deliberately (e.g., “copy and paste” actions)

or inadvertently by a developer during development and

the new context. For example, if a driver is required for a

new printer model, a developer could copy the driver code

from an older printer model and then modify it. Inconsistent

changes can also occur accidentally. A developer may be

unaware of a clone pair, and cause an inconsistency by only

changing one half of the clone pair. This inconsistency could

cause a software fault. If a fault is found in one clone and

fixed, but not propagated to the other clone in the clone pair,

the fault remains in the system. For example, a fault might

be found in the old printer driver code and fixed, but the fix

is not propagated to the new printer driver. For these reasons,

previous studies [1] have argued that accidental inconsistent

changes make code clones more prone to faults.

Late propagation occurs when a clone pair that under-

goes one or more inconsistent changes followed by a re-

synchronizing change [2]. The re-synchronization of the

code clones indicates that the gap in consistency is acci-

dental. Since accidental inconsistencies are considered risky

[3], the presence of late propagation in clone genealogies

can be an indicator of risky, fault-prone code.

Many studies have been performed on the evolution of

clones. A few (e.g., [2], [3]) have studied late propagation,

and indicated that late propagation genealogies are more

fault-prone than other clone genealogies. Thummalapenta et

al. began the initial work in examining the characteristics of

late propagation. The authors measured the delay between

an inconsistent change and a re-synchronizing change and

related the delay to software faults. In our work, we examine

More Detailed Genealogy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-100-320.jpg)

![LP In Type-3 Clones

Late propagation of Type-3 Clones

Saman Bazrafshan

Universit¨at Bremen

saman.bazrafshan@informatik.uni-bremen.de

Abstract

Type-3 clones are duplicated source code fragments

that span two or more identical sequences of tokens

(whitespace and comments are ignored) that form a

contiguous source code fragment interrupted by non-

identical token sequences. Several studies on the evo-

lution of code clones have been conducted to detect

patterns that can help to manage clones [3,6]. One of

those patterns that is assumed to be of special inter-

est is late propagation [1,2,4]. In this paper, ways of

detecting late propagation in the evolution of type-3

clones are proposed and discussed.

1 Introduction

During the last years, di↵erent studies focused on de-

tecting clone patterns that are considered to have

a negative impact on code quality and therefore on

maintainability of software. Missing or inconsistent

propagation of changes to clones is identified as one

pattern that may introduce new defects or prevent the

removal of existing ones. To find these clone patterns

and enable clone management, a series of tools have

been introduced—including clone detectors and clone

genealogy extractors. Clones reported by a clone de-

tector are generally distinguished according to their

level of similarity. Clones that are identical except for

comments and whitespaces are called type-1 clones.

Type-2 clones extend type-1 clones by tolerating dif-

intentionally changed inconsistently [1,2,4].

2 Late Propagation of Near-Miss

Clones

The definition of a late propagation regarding identi-

cal clones is straightforward: an inconsistent modifica-

tion of an identical clone causing the fragments to be

non-identical until another inconsistent change to the

fragments makes them identical again. However, the

definition is not suitable for near-miss clones because

they are not completely identical–changes between the

identical and the non-identical parts have to be dif-

ferentiated. The challenging question that arises from

this fact is:

What are the essential characteristics of a

change that makes an inconsistent change to

a near-miss clone consistent at a later point

of time?

One way to define the late propagation pattern for

near-miss clones is to focus exclusively on the identical

parts of a clone disregarding the gaps as the gaps are

already not common between the cloned fragments.

In this case, we would regard a near-miss clone to

be changed consistently if the identical parts undergo

the same modifications and continue to be identical–

analogously to the definition of a late propagation of

identical clones. Hence, to recognize an inconsistent

ECEASST

Late Propagation in Near-Miss Clones: An Empirical Study

Manishankar Mondal1, Chanchal K. Roy2, Kevin A. Schneider3

1 mshankar.mondal@usask.ca, https://homepage.usask.ca/⇠mam815/

2 croy@cs.usask.ca, http://www.cs.usask.ca/⇠croy/

3 kevin.schneider@usask.ca, http://www.cs.usask.ca/⇠kas/

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Abstract:

If two or more code fragments in the code-base of a software system are exactly

or nearly similar to one another, we call them code clones. It is often important

that updates (i.e., changes) in one clone fragment should be propagated to the other

similar clone fragments to ensure consistency. However, if there is a delay in this

propagation because of unawareness, the system might behave inconsistently. This

delay in propagation, also known as late propagation, has been investigated by a

number of existing studies. However, the existing studies did not investigate the

intensity as well as the effect of late propagation in different types of clones sepa-

rately. Also, late propagation in Type 3 clones is yet to investigate. In this research

work we investigate late propagation in three types of clones (Type 1, Type 2, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-108-320.jpg)

![LP In Type-3 Clones

Late propagation of Type-3 Clones

Saman Bazrafshan

Universit¨at Bremen

saman.bazrafshan@informatik.uni-bremen.de

Abstract

Type-3 clones are duplicated source code fragments

that span two or more identical sequences of tokens

(whitespace and comments are ignored) that form a

contiguous source code fragment interrupted by non-

identical token sequences. Several studies on the evo-

lution of code clones have been conducted to detect

patterns that can help to manage clones [3,6]. One of

those patterns that is assumed to be of special inter-

est is late propagation [1,2,4]. In this paper, ways of

detecting late propagation in the evolution of type-3

clones are proposed and discussed.

1 Introduction

During the last years, di↵erent studies focused on de-

tecting clone patterns that are considered to have

a negative impact on code quality and therefore on

maintainability of software. Missing or inconsistent

propagation of changes to clones is identified as one

pattern that may introduce new defects or prevent the

removal of existing ones. To find these clone patterns

and enable clone management, a series of tools have

been introduced—including clone detectors and clone

genealogy extractors. Clones reported by a clone de-

tector are generally distinguished according to their

level of similarity. Clones that are identical except for

comments and whitespaces are called type-1 clones.

Type-2 clones extend type-1 clones by tolerating dif-

intentionally changed inconsistently [1,2,4].

2 Late Propagation of Near-Miss

Clones

The definition of a late propagation regarding identi-

cal clones is straightforward: an inconsistent modifica-

tion of an identical clone causing the fragments to be

non-identical until another inconsistent change to the

fragments makes them identical again. However, the

definition is not suitable for near-miss clones because

they are not completely identical–changes between the

identical and the non-identical parts have to be dif-

ferentiated. The challenging question that arises from

this fact is:

What are the essential characteristics of a

change that makes an inconsistent change to

a near-miss clone consistent at a later point

of time?

One way to define the late propagation pattern for

near-miss clones is to focus exclusively on the identical

parts of a clone disregarding the gaps as the gaps are

already not common between the cloned fragments.

In this case, we would regard a near-miss clone to

be changed consistently if the identical parts undergo

the same modifications and continue to be identical–

analogously to the definition of a late propagation of

identical clones. Hence, to recognize an inconsistent

ECEASST

Late Propagation in Near-Miss Clones: An Empirical Study

Manishankar Mondal1, Chanchal K. Roy2, Kevin A. Schneider3

1 mshankar.mondal@usask.ca, https://homepage.usask.ca/⇠mam815/

2 croy@cs.usask.ca, http://www.cs.usask.ca/⇠croy/

3 kevin.schneider@usask.ca, http://www.cs.usask.ca/⇠kas/

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Abstract:

If two or more code fragments in the code-base of a software system are exactly

or nearly similar to one another, we call them code clones. It is often important

that updates (i.e., changes) in one clone fragment should be propagated to the other

similar clone fragments to ensure consistency. However, if there is a delay in this

propagation because of unawareness, the system might behave inconsistently. This

delay in propagation, also known as late propagation, has been investigated by a

number of existing studies. However, the existing studies did not investigate the

intensity as well as the effect of late propagation in different types of clones sepa-

rately. Also, late propagation in Type 3 clones is yet to investigate. In this research

work we investigate late propagation in three types of clones (Type 1, Type 2, and

More late propagations in type-3

clones than in others](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-109-320.jpg)

![LP In Type-3 Clones

Late propagation of Type-3 Clones

Saman Bazrafshan

Universit¨at Bremen

saman.bazrafshan@informatik.uni-bremen.de

Abstract

Type-3 clones are duplicated source code fragments

that span two or more identical sequences of tokens

(whitespace and comments are ignored) that form a

contiguous source code fragment interrupted by non-

identical token sequences. Several studies on the evo-

lution of code clones have been conducted to detect

patterns that can help to manage clones [3,6]. One of

those patterns that is assumed to be of special inter-

est is late propagation [1,2,4]. In this paper, ways of

detecting late propagation in the evolution of type-3

clones are proposed and discussed.

1 Introduction

During the last years, di↵erent studies focused on de-

tecting clone patterns that are considered to have

a negative impact on code quality and therefore on

maintainability of software. Missing or inconsistent

propagation of changes to clones is identified as one

pattern that may introduce new defects or prevent the

removal of existing ones. To find these clone patterns

and enable clone management, a series of tools have

been introduced—including clone detectors and clone

genealogy extractors. Clones reported by a clone de-

tector are generally distinguished according to their

level of similarity. Clones that are identical except for

comments and whitespaces are called type-1 clones.

Type-2 clones extend type-1 clones by tolerating dif-

intentionally changed inconsistently [1,2,4].

2 Late Propagation of Near-Miss

Clones

The definition of a late propagation regarding identi-

cal clones is straightforward: an inconsistent modifica-

tion of an identical clone causing the fragments to be

non-identical until another inconsistent change to the

fragments makes them identical again. However, the

definition is not suitable for near-miss clones because

they are not completely identical–changes between the

identical and the non-identical parts have to be dif-

ferentiated. The challenging question that arises from

this fact is:

What are the essential characteristics of a

change that makes an inconsistent change to

a near-miss clone consistent at a later point

of time?

One way to define the late propagation pattern for

near-miss clones is to focus exclusively on the identical

parts of a clone disregarding the gaps as the gaps are

already not common between the cloned fragments.

In this case, we would regard a near-miss clone to

be changed consistently if the identical parts undergo

the same modifications and continue to be identical–

analogously to the definition of a late propagation of

identical clones. Hence, to recognize an inconsistent

ECEASST

Late Propagation in Near-Miss Clones: An Empirical Study

Manishankar Mondal1, Chanchal K. Roy2, Kevin A. Schneider3

1 mshankar.mondal@usask.ca, https://homepage.usask.ca/⇠mam815/

2 croy@cs.usask.ca, http://www.cs.usask.ca/⇠croy/

3 kevin.schneider@usask.ca, http://www.cs.usask.ca/⇠kas/

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Abstract:

If two or more code fragments in the code-base of a software system are exactly

or nearly similar to one another, we call them code clones. It is often important

that updates (i.e., changes) in one clone fragment should be propagated to the other

similar clone fragments to ensure consistency. However, if there is a delay in this

propagation because of unawareness, the system might behave inconsistently. This

delay in propagation, also known as late propagation, has been investigated by a

number of existing studies. However, the existing studies did not investigate the

intensity as well as the effect of late propagation in different types of clones sepa-

rately. Also, late propagation in Type 3 clones is yet to investigate. In this research

work we investigate late propagation in three types of clones (Type 1, Type 2, and

More late propagations in type-3

clones than in others

Late propagations occur in small

(block-size) clones](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-110-320.jpg)

![A Study of Consistent and Inconsistent Changes to Code Clones

Jens Krinke

FernUniversit¨at in Hagen, Germany

krinke@acm.org

Abstract

Code Cloning is regarded as a threat to software main-

tenance, because it is generally assumed that a change to

a code clone usually has to be applied to the other clones

of the clone group as well. However, there exists little

empirical data that supports this assumption. This paper

presents a study on the changes applied to code clones in

open source software systems based on the changes between

versions of the system. It is analyzed if changes to code

clones are consistent to all code clones of a clone group or

not. The results show that usually half of the changes to

code clone groups are inconsistent changes. Moreover, the

study observes that when there are inconsistent changes to

a code clone group in a near version, it is rarely the case

that there are additional changes in later versions such that

the code clone group then has only consistent changes.

1 Introduction

Duplicated code is common in all kind of software sys-

tems. Although cut-copy-paste (-and-adapt) techniques are

considered bad practice, every programmer uses them.

Since these practices involve both duplication and mod-

ification, they are collectively called code cloning. While

the duplicated code is called a code clone. A clone group

whether or not the above mentioned problems are relevant

in practice. Kim et al. [15] investigated the evolution of

code clones and provided a classification for evolving code

clones. Their work already showed that during the evolution

of the code clones, consistent changes to the code clones

of a group are fewer than anticipated. Aversano et al. [4]

did a similar study and they state “that the majority of clone

classes is always maintained consistently.” Geiger et al. [10]

studied the relation of code clone groups and change cou-

plings (files which are committed at the same time, by the

same author, and with the same modification description),

but could not find a (strong) relation. Therefore, this work

will present an empirical study that verifies the following

hypothesis:

During the evolution of a system, code clones of

a clone group are changed consistently.

Of course, a system may contain bugs where a change

has been applied to some code clones, but has been forgot-

ten for other code clones of the clone group. For stable

systems it can be assumed that such bugs will be resolved

at a later time. This results in a second hypothesis:

During the evolution of a system, if code clones

of a clone group are not changed consistently, the

missing changes will appear in a later version.

ECEASST

Studying Late Propagations in Code Clone Evolution Using

Software Repository Mining

Hsiao Hui Mui1, Andy Zaidman1 and Martin Pinzger1

1 hsiaomui@gmail.com, a.e.zaidman@tudelft.nl

Software Engineering Research Group

Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands

2 martin.pinzger@aau.at

Software Engineering Research Group

University of Klagenfurt, Austria

Abstract: In the code clone evolution community, the Late Propagation (LP) has

been identified as one of the clone evolution patterns that can potentially lead to

software defects. An LP occurs when instances of a clone pair are changed consis-

tently, but not at the same time. The clone instance, which receives the update at a

later time, might exhibit unintended behavior if the modification was a bugfix. In

this paper, we present an approach to extract LPs from software repositories. Sub-

Inconsistent? LP?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-111-320.jpg)

![A Study of Consistent and Inconsistent Changes to Code Clones

Jens Krinke

FernUniversit¨at in Hagen, Germany

krinke@acm.org

Abstract

Code Cloning is regarded as a threat to software main-

tenance, because it is generally assumed that a change to

a code clone usually has to be applied to the other clones

of the clone group as well. However, there exists little

empirical data that supports this assumption. This paper

presents a study on the changes applied to code clones in

open source software systems based on the changes between

versions of the system. It is analyzed if changes to code

clones are consistent to all code clones of a clone group or

not. The results show that usually half of the changes to

code clone groups are inconsistent changes. Moreover, the

study observes that when there are inconsistent changes to

a code clone group in a near version, it is rarely the case

that there are additional changes in later versions such that

the code clone group then has only consistent changes.

1 Introduction

Duplicated code is common in all kind of software sys-

tems. Although cut-copy-paste (-and-adapt) techniques are

considered bad practice, every programmer uses them.

Since these practices involve both duplication and mod-

ification, they are collectively called code cloning. While

the duplicated code is called a code clone. A clone group

whether or not the above mentioned problems are relevant

in practice. Kim et al. [15] investigated the evolution of

code clones and provided a classification for evolving code

clones. Their work already showed that during the evolution

of the code clones, consistent changes to the code clones

of a group are fewer than anticipated. Aversano et al. [4]

did a similar study and they state “that the majority of clone

classes is always maintained consistently.” Geiger et al. [10]

studied the relation of code clone groups and change cou-

plings (files which are committed at the same time, by the

same author, and with the same modification description),

but could not find a (strong) relation. Therefore, this work

will present an empirical study that verifies the following

hypothesis:

During the evolution of a system, code clones of

a clone group are changed consistently.

Of course, a system may contain bugs where a change

has been applied to some code clones, but has been forgot-

ten for other code clones of the clone group. For stable

systems it can be assumed that such bugs will be resolved

at a later time. This results in a second hypothesis:

During the evolution of a system, if code clones

of a clone group are not changed consistently, the

missing changes will appear in a later version.

ECEASST

Studying Late Propagations in Code Clone Evolution Using

Software Repository Mining

Hsiao Hui Mui1, Andy Zaidman1 and Martin Pinzger1

1 hsiaomui@gmail.com, a.e.zaidman@tudelft.nl

Software Engineering Research Group

Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands

2 martin.pinzger@aau.at

Software Engineering Research Group

University of Klagenfurt, Austria

Abstract: In the code clone evolution community, the Late Propagation (LP) has

been identified as one of the clone evolution patterns that can potentially lead to

software defects. An LP occurs when instances of a clone pair are changed consis-

tently, but not at the same time. The clone instance, which receives the update at a

later time, might exhibit unintended behavior if the modification was a bugfix. In

this paper, we present an approach to extract LPs from software repositories. Sub-

Consistent changes occur half of the time

Inconsistent? LP?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-112-320.jpg)

![A Study of Consistent and Inconsistent Changes to Code Clones

Jens Krinke

FernUniversit¨at in Hagen, Germany

krinke@acm.org

Abstract

Code Cloning is regarded as a threat to software main-

tenance, because it is generally assumed that a change to

a code clone usually has to be applied to the other clones

of the clone group as well. However, there exists little

empirical data that supports this assumption. This paper

presents a study on the changes applied to code clones in

open source software systems based on the changes between

versions of the system. It is analyzed if changes to code

clones are consistent to all code clones of a clone group or

not. The results show that usually half of the changes to

code clone groups are inconsistent changes. Moreover, the

study observes that when there are inconsistent changes to

a code clone group in a near version, it is rarely the case

that there are additional changes in later versions such that

the code clone group then has only consistent changes.

1 Introduction

Duplicated code is common in all kind of software sys-

tems. Although cut-copy-paste (-and-adapt) techniques are

considered bad practice, every programmer uses them.

Since these practices involve both duplication and mod-

ification, they are collectively called code cloning. While

the duplicated code is called a code clone. A clone group

whether or not the above mentioned problems are relevant

in practice. Kim et al. [15] investigated the evolution of

code clones and provided a classification for evolving code

clones. Their work already showed that during the evolution

of the code clones, consistent changes to the code clones

of a group are fewer than anticipated. Aversano et al. [4]

did a similar study and they state “that the majority of clone

classes is always maintained consistently.” Geiger et al. [10]

studied the relation of code clone groups and change cou-

plings (files which are committed at the same time, by the

same author, and with the same modification description),

but could not find a (strong) relation. Therefore, this work

will present an empirical study that verifies the following

hypothesis:

During the evolution of a system, code clones of

a clone group are changed consistently.

Of course, a system may contain bugs where a change

has been applied to some code clones, but has been forgot-

ten for other code clones of the clone group. For stable

systems it can be assumed that such bugs will be resolved

at a later time. This results in a second hypothesis:

During the evolution of a system, if code clones

of a clone group are not changed consistently, the

missing changes will appear in a later version.

ECEASST

Studying Late Propagations in Code Clone Evolution Using

Software Repository Mining

Hsiao Hui Mui1, Andy Zaidman1 and Martin Pinzger1

1 hsiaomui@gmail.com, a.e.zaidman@tudelft.nl

Software Engineering Research Group

Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands

2 martin.pinzger@aau.at

Software Engineering Research Group

University of Klagenfurt, Austria

Abstract: In the code clone evolution community, the Late Propagation (LP) has

been identified as one of the clone evolution patterns that can potentially lead to

software defects. An LP occurs when instances of a clone pair are changed consis-

tently, but not at the same time. The clone instance, which receives the update at a

later time, might exhibit unintended behavior if the modification was a bugfix. In

this paper, we present an approach to extract LPs from software repositories. Sub-

LP seldom occurs, and most of them re-

synchronize within one day

Consistent changes occur half of the time

Inconsistent? LP?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-113-320.jpg)

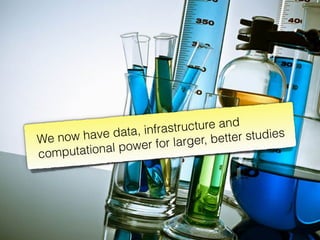

![Release Level Analysis

Science of Computer Programming ( ) –

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Science of Computer Programming

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scico

An empirical study on inconsistent changes to code clones at the

release level

Nicolas Bettenburg⇤

, Weiyi Shang, Walid M. Ibrahim, Bram Adams, Ying Zou,

Ahmed E. Hassan

Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Software engineering

Maintenance management

Reuse models

Clone detection

Maintainability

Software evolution

a b s t r a c t

To study the impact of code clones on software quality, researchers typically carry out

their studies based on fine-grained analysis of inconsistent changes at the revision level.

As a result, they capture much of the chaotic and experimental nature inherent in any on-

going software development process. Analyzing highly fluctuating and short-lived clones

is likely to exaggerate the ill effects of inconsistent changes on the quality of the released

software product, as perceived by the end user. To gain a broader perspective, we perform

an empirical study on the effect of inconsistent changes on software quality at the release

level. Based on a case study on three open source software systems, we observe that

only 1.02%–4.00% of all clone genealogies introduce software defects at the release level,

as opposed to the substantially higher percentages reported by previous studies at the

revision level. Our findings suggest that clones do not have a significant impact on the

post-release quality of the studied systems, and that the developers are able to effectively

manage the evolution of cloned code.

© 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Code clones are the source of heated debates among software maintenance researchers. Developers typically clone (copy)

existing pieces of code in order to jumpstart the development of a new feature, or to reuse robust parts of the source code

for new development. However, unless a clone is reused as is, developers quickly lose track of the link between the clone

and the cloned piece of code, especially after some local modifications. Losing the links between clones increases the risk

of inconsistent changes. These are code changes that are applied to only one clone, whereas they should propagate to all

clones, such as defect fixing changes.

There is no consensus on whether the positive traits of cloning, such as effective reuse, outweigh its drawbacks, such as

increased risk of deteriorated software quality. Many researchers consider clones to be harmful [3,6,14,21,22,27,36], due to

the belief that inconsistent changes increase both maintenance effort and the likelihood of introducing defects. Yet, other

researchers do not find empirical evidence of harm [39,47], or even establish cloning as a valuable software engineering

method to overcome language limitations or to specialize common parts of the code [10,24–26]. It is not yet clear which of

these two visions prevails, or whether the right vision depends on the software system at hand [15,43,47].

Empirical studies on code clones almost exclusively focus on the impact of cloning on developers, such as the developers’

ability to keep track of all related clones in a clone group and their ability to consistently propagate changes to all clones.

Many studies analyze inconsistent changes to clones and the general evolution (genealogy) of clone groups across very small

Evaluating Code Clone Genealogies at Release Level: An Empirical Study

Ripon K. Saha, Muhammad Asaduzzaman, Minhaz F. Zibran, Chanchal K. Roy, and Kevin A. Schneider

Department of Computer Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada S7N 5C9

{ripon.saha, md.asad, minhaz.zibran, chanchal.roy, kevin.schneider}@usask.ca

Abstract

Code clone genealogies show how clone groups

evolve with the evolution of the associated software

system, and thus could provide important insights on

the maintenance implications of clones. In this paper,

we provide an in-depth empirical study for evaluating

clone genealogies in evolving open source systems at

the release level. We develop a clone genealogy

extractor, examine 17 open source C, Java, C++ and

C# systems of diverse varieties and study different

dimensions of how clone groups evolve with the

evolution of the software systems. Our study shows that

majority of the clone groups of the clone genealogies

either propagate without any syntactic changes or

change consistently in the subsequent releases, and

that many of the genealogies remain alive during the

evolution. These findings seem to be consistent with the

findings of a previous study that clones may not be as

detrimental in software maintenance as believed to be

(at least by many of us), and that instead of

aggressively refactoring clones, we should possibly

focus on tracking and managing clones during the

evolution of software systems.

an essential part of software maintenance. However,

due to the intense use of template-based programming

[12], a certain amount of clones are likely acceptable.

Previous studies were highly influenced by the idea

that clones are harmful and can be removed through

refactoring [15]. This notion has been challenged by

the work of Kim et al. [15]. They provided a clone

genealogy model and analyzed the clone genealogies

of two open source software systems. While a clone

group consists of a set of code fragments in a particular

version of a software that are clones to each other, a

genealogy of a clone group describes how the code

fragments of that clone group propagate during the

evolution of the subject system. Each clone genealogy

consists of a set of clone lineages that originate from

the same clone group (source). A clone lineage is a

directed acyclic graph that describes the evolution

history of a clone group from the beginning to the final

release of the software system. The empirical study

described by Kim et al. on code clone genealogy

reveals that clones are not always harmful.

Programmers intentionally practice code cloning to

achieve certain benefits [12, 13]. During the

development of a software system, many clones are

short lived. Refactoring them aggressively can](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-116-320.jpg)

![Release Level Analysis

Science of Computer Programming ( ) –

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Science of Computer Programming

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scico

An empirical study on inconsistent changes to code clones at the

release level

Nicolas Bettenburg⇤

, Weiyi Shang, Walid M. Ibrahim, Bram Adams, Ying Zou,

Ahmed E. Hassan

Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Software engineering

Maintenance management

Reuse models

Clone detection

Maintainability

Software evolution

a b s t r a c t

To study the impact of code clones on software quality, researchers typically carry out

their studies based on fine-grained analysis of inconsistent changes at the revision level.

As a result, they capture much of the chaotic and experimental nature inherent in any on-

going software development process. Analyzing highly fluctuating and short-lived clones

is likely to exaggerate the ill effects of inconsistent changes on the quality of the released

software product, as perceived by the end user. To gain a broader perspective, we perform

an empirical study on the effect of inconsistent changes on software quality at the release

level. Based on a case study on three open source software systems, we observe that

only 1.02%–4.00% of all clone genealogies introduce software defects at the release level,

as opposed to the substantially higher percentages reported by previous studies at the

revision level. Our findings suggest that clones do not have a significant impact on the

post-release quality of the studied systems, and that the developers are able to effectively

manage the evolution of cloned code.

© 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Code clones are the source of heated debates among software maintenance researchers. Developers typically clone (copy)

existing pieces of code in order to jumpstart the development of a new feature, or to reuse robust parts of the source code

for new development. However, unless a clone is reused as is, developers quickly lose track of the link between the clone

and the cloned piece of code, especially after some local modifications. Losing the links between clones increases the risk

of inconsistent changes. These are code changes that are applied to only one clone, whereas they should propagate to all

clones, such as defect fixing changes.

There is no consensus on whether the positive traits of cloning, such as effective reuse, outweigh its drawbacks, such as

increased risk of deteriorated software quality. Many researchers consider clones to be harmful [3,6,14,21,22,27,36], due to

the belief that inconsistent changes increase both maintenance effort and the likelihood of introducing defects. Yet, other

researchers do not find empirical evidence of harm [39,47], or even establish cloning as a valuable software engineering

method to overcome language limitations or to specialize common parts of the code [10,24–26]. It is not yet clear which of

these two visions prevails, or whether the right vision depends on the software system at hand [15,43,47].

Empirical studies on code clones almost exclusively focus on the impact of cloning on developers, such as the developers’

ability to keep track of all related clones in a clone group and their ability to consistently propagate changes to all clones.

Many studies analyze inconsistent changes to clones and the general evolution (genealogy) of clone groups across very small

Evaluating Code Clone Genealogies at Release Level: An Empirical Study

Ripon K. Saha, Muhammad Asaduzzaman, Minhaz F. Zibran, Chanchal K. Roy, and Kevin A. Schneider

Department of Computer Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada S7N 5C9

{ripon.saha, md.asad, minhaz.zibran, chanchal.roy, kevin.schneider}@usask.ca

Abstract

Code clone genealogies show how clone groups

evolve with the evolution of the associated software

system, and thus could provide important insights on

the maintenance implications of clones. In this paper,

we provide an in-depth empirical study for evaluating

clone genealogies in evolving open source systems at

the release level. We develop a clone genealogy

extractor, examine 17 open source C, Java, C++ and

C# systems of diverse varieties and study different

dimensions of how clone groups evolve with the

evolution of the software systems. Our study shows that

majority of the clone groups of the clone genealogies

either propagate without any syntactic changes or

change consistently in the subsequent releases, and

that many of the genealogies remain alive during the

evolution. These findings seem to be consistent with the

findings of a previous study that clones may not be as

detrimental in software maintenance as believed to be

(at least by many of us), and that instead of

aggressively refactoring clones, we should possibly

focus on tracking and managing clones during the

evolution of software systems.

an essential part of software maintenance. However,

due to the intense use of template-based programming

[12], a certain amount of clones are likely acceptable.

Previous studies were highly influenced by the idea

that clones are harmful and can be removed through

refactoring [15]. This notion has been challenged by

the work of Kim et al. [15]. They provided a clone

genealogy model and analyzed the clone genealogies

of two open source software systems. While a clone

group consists of a set of code fragments in a particular

version of a software that are clones to each other, a

genealogy of a clone group describes how the code

fragments of that clone group propagate during the

evolution of the subject system. Each clone genealogy

consists of a set of clone lineages that originate from

the same clone group (source). A clone lineage is a

directed acyclic graph that describes the evolution

history of a clone group from the beginning to the final

release of the software system. The empirical study

described by Kim et al. on code clone genealogy

reveals that clones are not always harmful.

Programmers intentionally practice code cloning to

achieve certain benefits [12, 13]. During the

development of a software system, many clones are

short lived. Refactoring them aggressively can

Most of the clone inconsistent changes are not

visible at release level](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-117-320.jpg)

![Risks for Clone Changes

Frequency and Risks of Changes to Clones

Nils Göde

University of Bremen

Bremen, Germany

nils@informatik.uni-bremen.de

Rainer Koschke

University of Bremen

Bremen, Germany

koschke@informatik.uni-bremen.de

ABSTRACT

Code Clones—duplicated source fragments—are said to in-

crease maintenance e↵ort and to facilitate problems caused

by inconsistent changes to identical parts. While this is cer-

tainly true for some clones and certainly not true for others,

it is unclear how many clones are real threats to the system’s

quality and need to be taken care of. Our analysis of clone

evolution in mature software projects shows that most clones

are rarely changed and the number of unintentional incon-

sistent changes to clones is small. We thus have to carefully

select the clones to be managed to avoid unnecessary e↵ort

managing clones with no risk potential.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

D.2.7 [Software Engineering]: Distribution, Maintenance,

and Enhancement—restructuring, reverse engineering, and

reengineering

General Terms

Experimentation, Measurement

Keywords

Software maintenance, clone detection, clone evolution

1. INTRODUCTION

Code clones are similar fragments of source code. There

are many problems caused by the presences of clones. Among

others, the source code becomes larger, change e↵ort in-

There certainly exist clones that are true threats to soft-

ware maintenance. Nevertheless, recent research [19, 20]

doubts the harmfulness of clones in general and lists nu-

merous situations in which clones are a reasonable design

decision. From the clone management perspective, it is de-

sirable to detect and manage only the harmful clones, be-

cause managing clones that have no negative e↵ects creates

only additional e↵ort.

Unfortunately, state-of-the-art clone tools detect and clas-

sify clones based only on similar structures in the source

code or one of its various representations. When it comes to

clone-related problems, however, the most important char-

acteristic of a clone is its change behavior and not its struc-

ture. Only if a clone changes, it causes additional change

e↵ort. Only if a clone changes, unintentional inconsistencies

can arise. If, on the other hand, a clone never changes, there

are no additional costs induced by propagating changes and

there is no risk of unwanted inconsistencies.

Our hypothesis is that many clones detected by state-of-

the-art tools are “structurally interesting” but irrelevant to

software maintenance because they never change during their

lifetime.

Up-to-date clone detectors can e ciently process and de-

tect clones within huge amounts of source code, consequently

delivering huge numbers of clones. In contrast, clone assess-

ment and deciding how to proceed can be very costly even for

individual clones as we have experienced with clones in our

own code [11]. Hence, having many unproblematic clones in

the detection results creates enormous overhead for assess-

ing and managing clones that do not threaten maintenance

because they never change.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mip-saner2017-complete-170303132903/85/Most-Influential-Paper-SANER-2017-118-320.jpg)

![Risks for Clone Changes

Frequency and Risks of Changes to Clones

Nils Göde

University of Bremen

Bremen, Germany

nils@informatik.uni-bremen.de

Rainer Koschke

University of Bremen

Bremen, Germany

koschke@informatik.uni-bremen.de

ABSTRACT

Code Clones—duplicated source fragments—are said to in-

crease maintenance e↵ort and to facilitate problems caused

by inconsistent changes to identical parts. While this is cer-

tainly true for some clones and certainly not true for others,

it is unclear how many clones are real threats to the system’s

quality and need to be taken care of. Our analysis of clone

evolution in mature software projects shows that most clones

are rarely changed and the number of unintentional incon-

sistent changes to clones is small. We thus have to carefully

select the clones to be managed to avoid unnecessary e↵ort

managing clones with no risk potential.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

D.2.7 [Software Engineering]: Distribution, Maintenance,

and Enhancement—restructuring, reverse engineering, and

reengineering

General Terms

Experimentation, Measurement

Keywords

Software maintenance, clone detection, clone evolution

1. INTRODUCTION

Code clones are similar fragments of source code. There

are many problems caused by the presences of clones. Among

others, the source code becomes larger, change e↵ort in-

There certainly exist clones that are true threats to soft-

ware maintenance. Nevertheless, recent research [19, 20]

doubts the harmfulness of clones in general and lists nu-

merous situations in which clones are a reasonable design

decision. From the clone management perspective, it is de-

sirable to detect and manage only the harmful clones, be-

cause managing clones that have no negative e↵ects creates

only additional e↵ort.

Unfortunately, state-of-the-art clone tools detect and clas-

sify clones based only on similar structures in the source

code or one of its various representations. When it comes to

clone-related problems, however, the most important char-

acteristic of a clone is its change behavior and not its struc-

ture. Only if a clone changes, it causes additional change

e↵ort. Only if a clone changes, unintentional inconsistencies