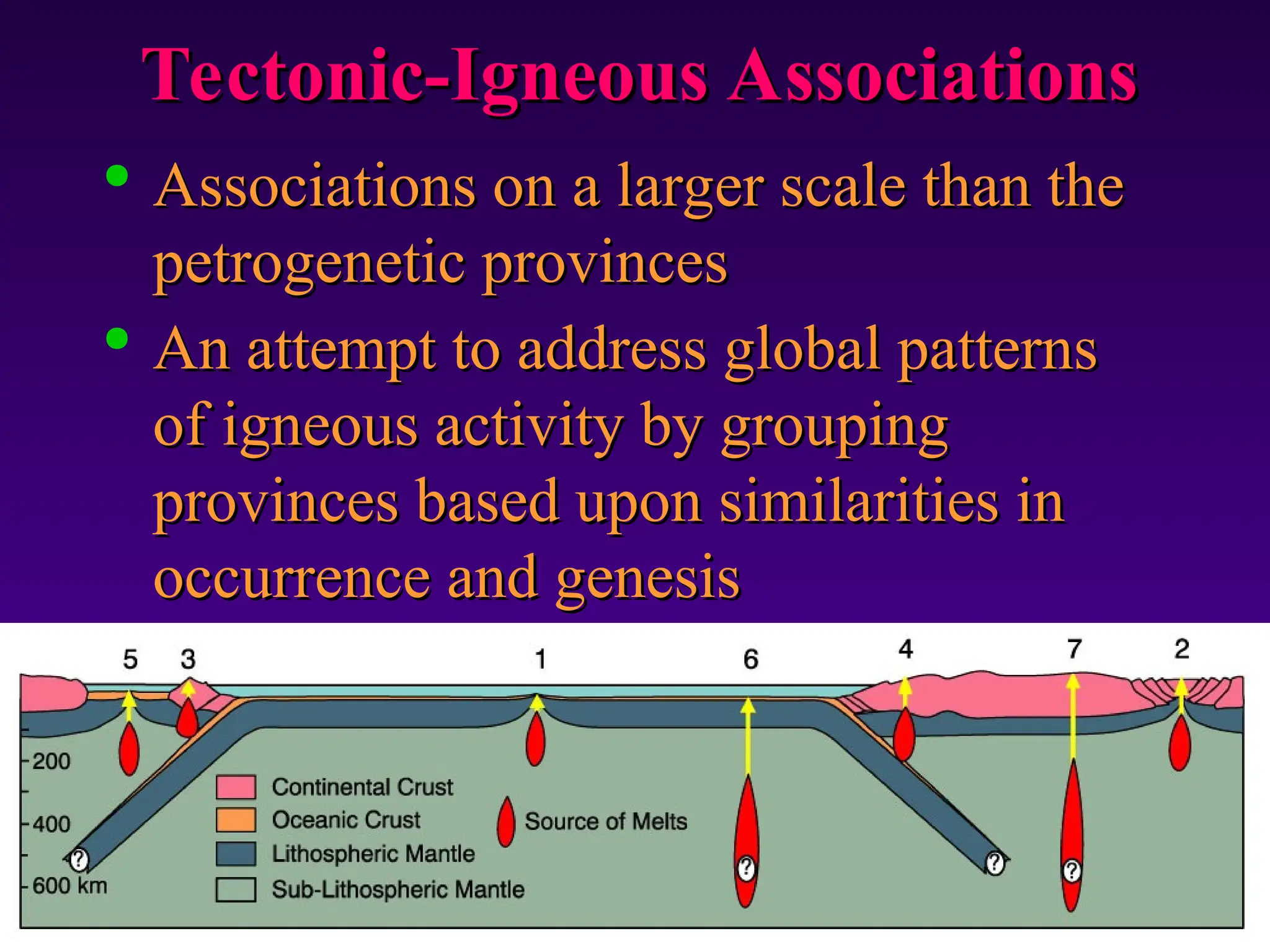

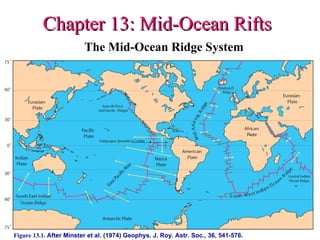

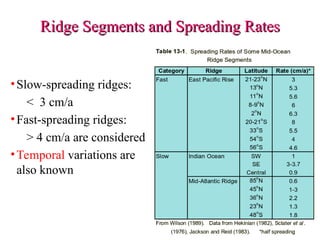

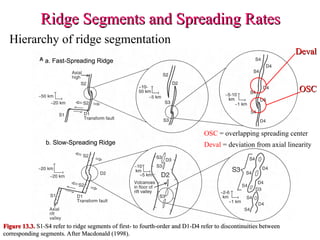

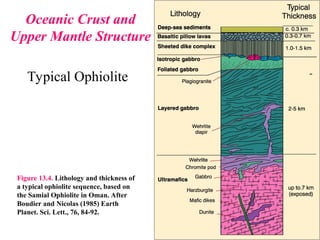

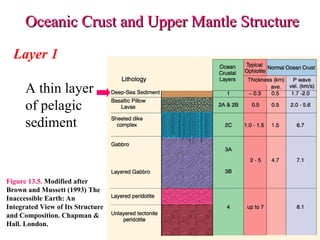

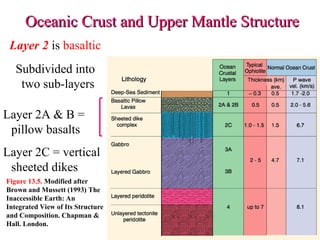

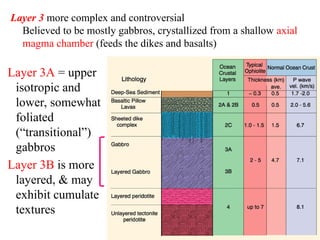

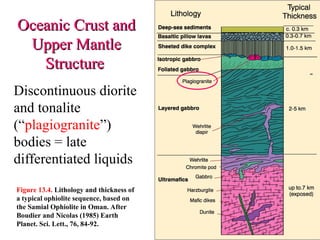

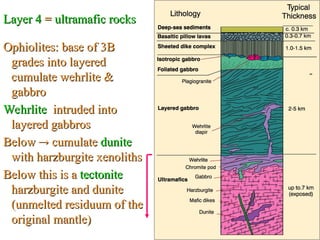

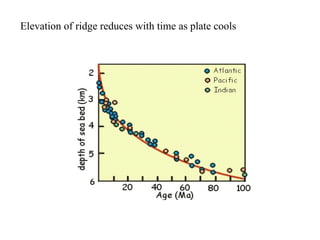

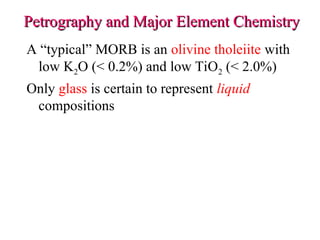

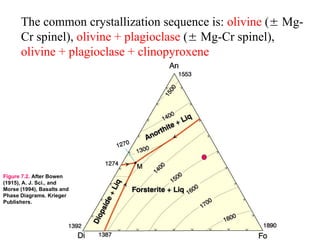

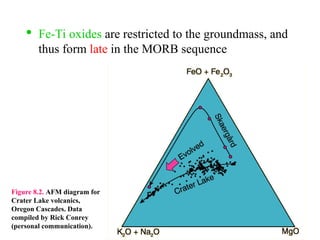

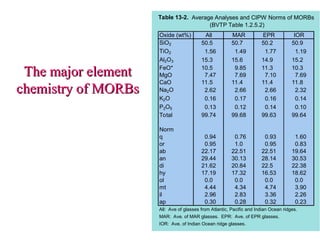

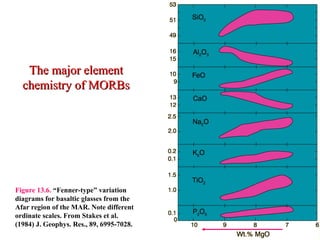

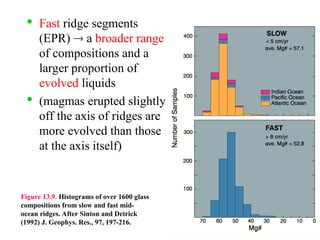

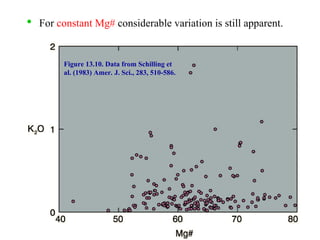

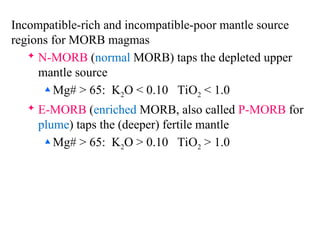

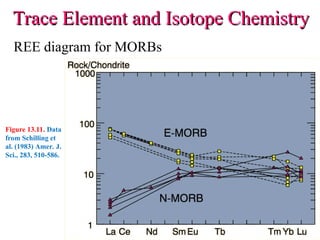

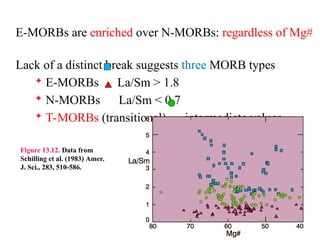

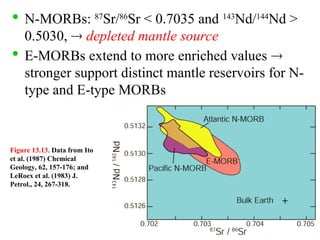

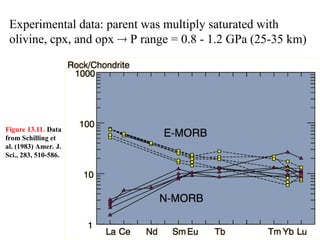

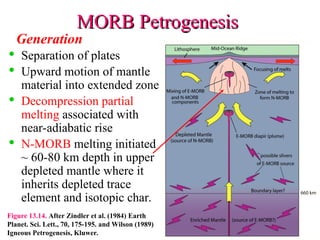

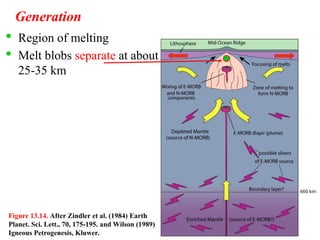

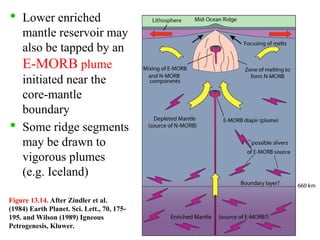

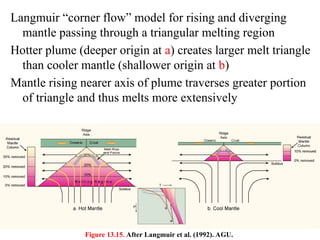

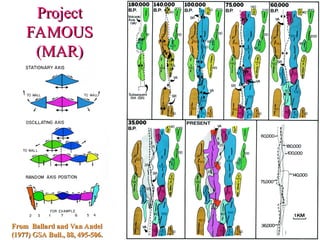

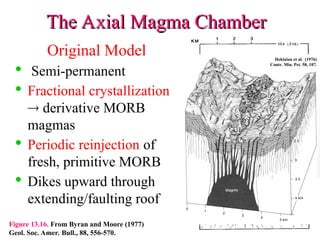

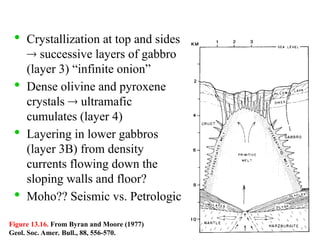

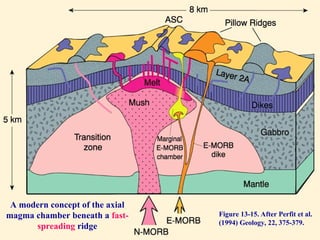

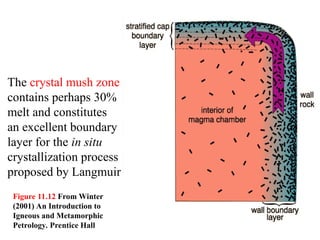

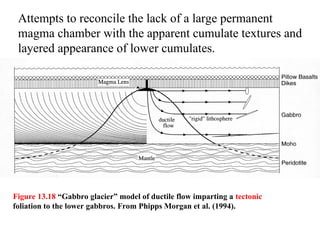

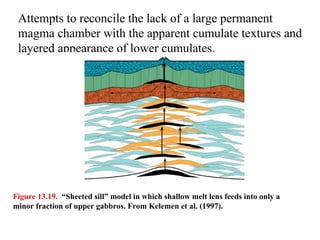

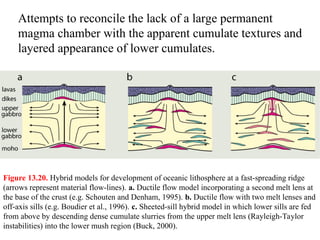

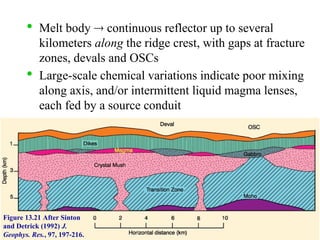

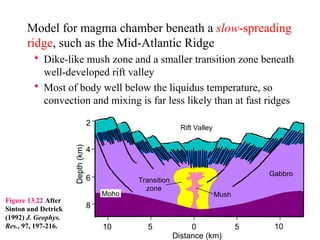

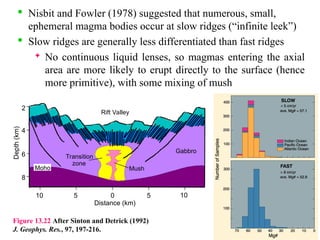

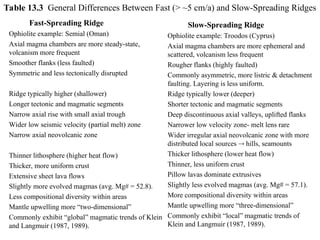

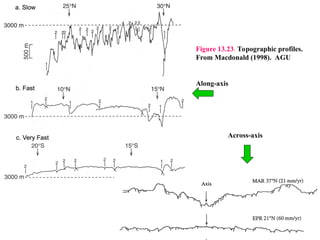

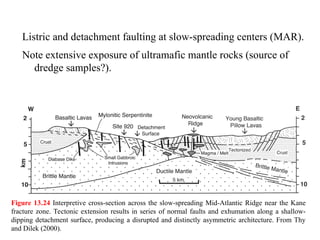

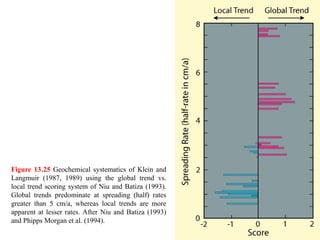

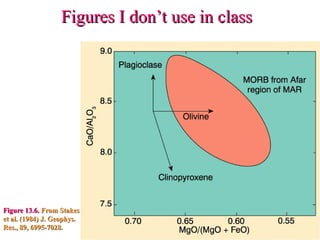

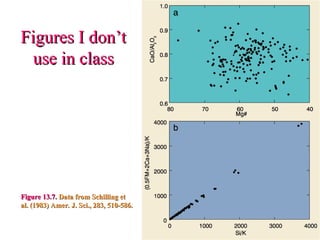

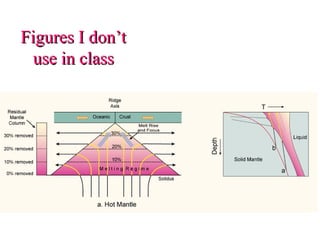

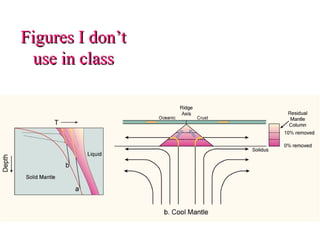

The document discusses tectonic-igneous associations and the classification of global igneous activity based on occurrence and genesis. It details mid-ocean ridge volcanism, ocean intra-plate volcanism, subduction-related volcanism, and the structure of oceanic crust and upper mantle, explaining the composition and variations found in basaltic magmas. Additionally, it explores the complexities of magma generation, including models of magma chambers and the dynamics of magma flow beneath oceans.