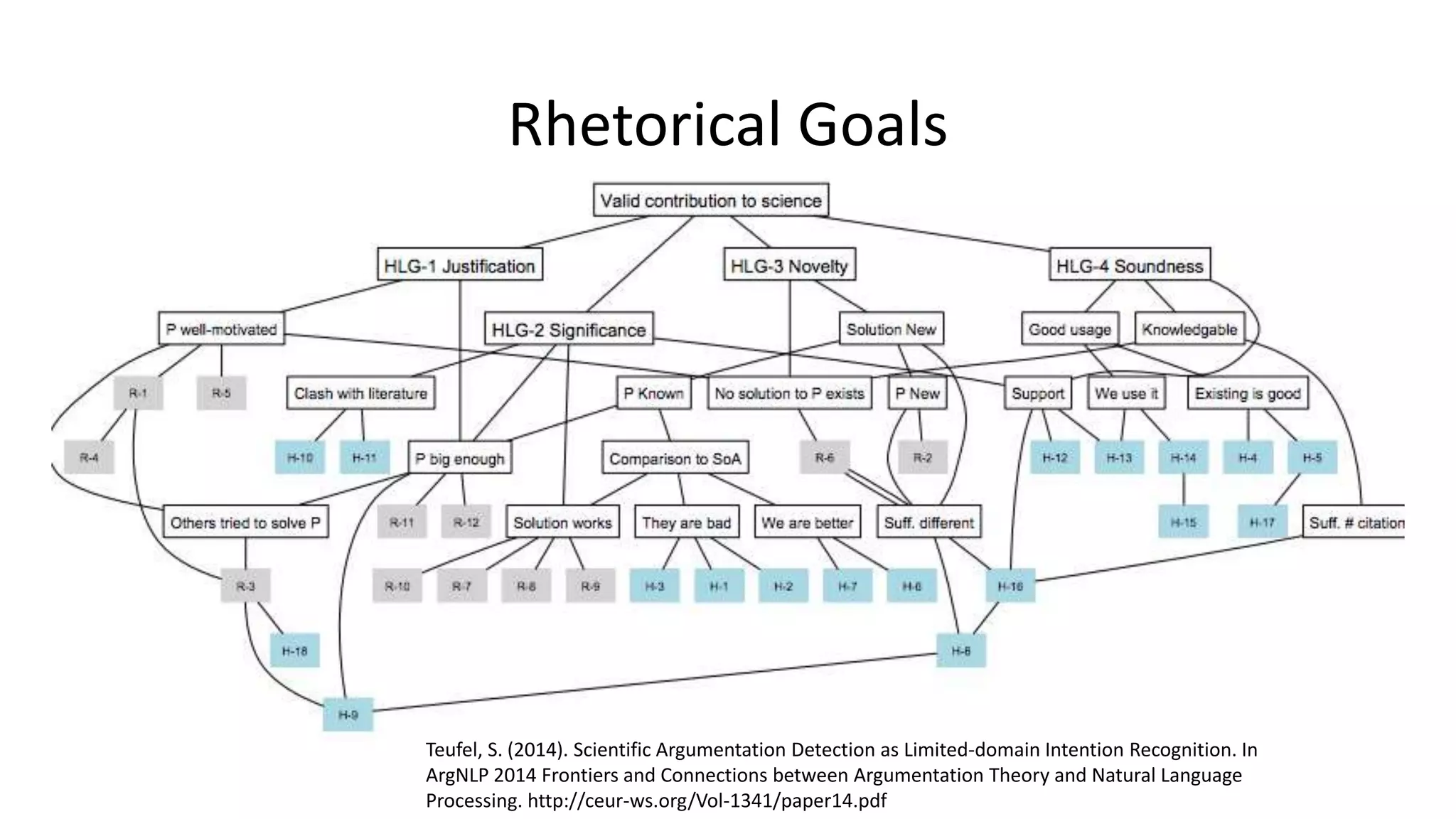

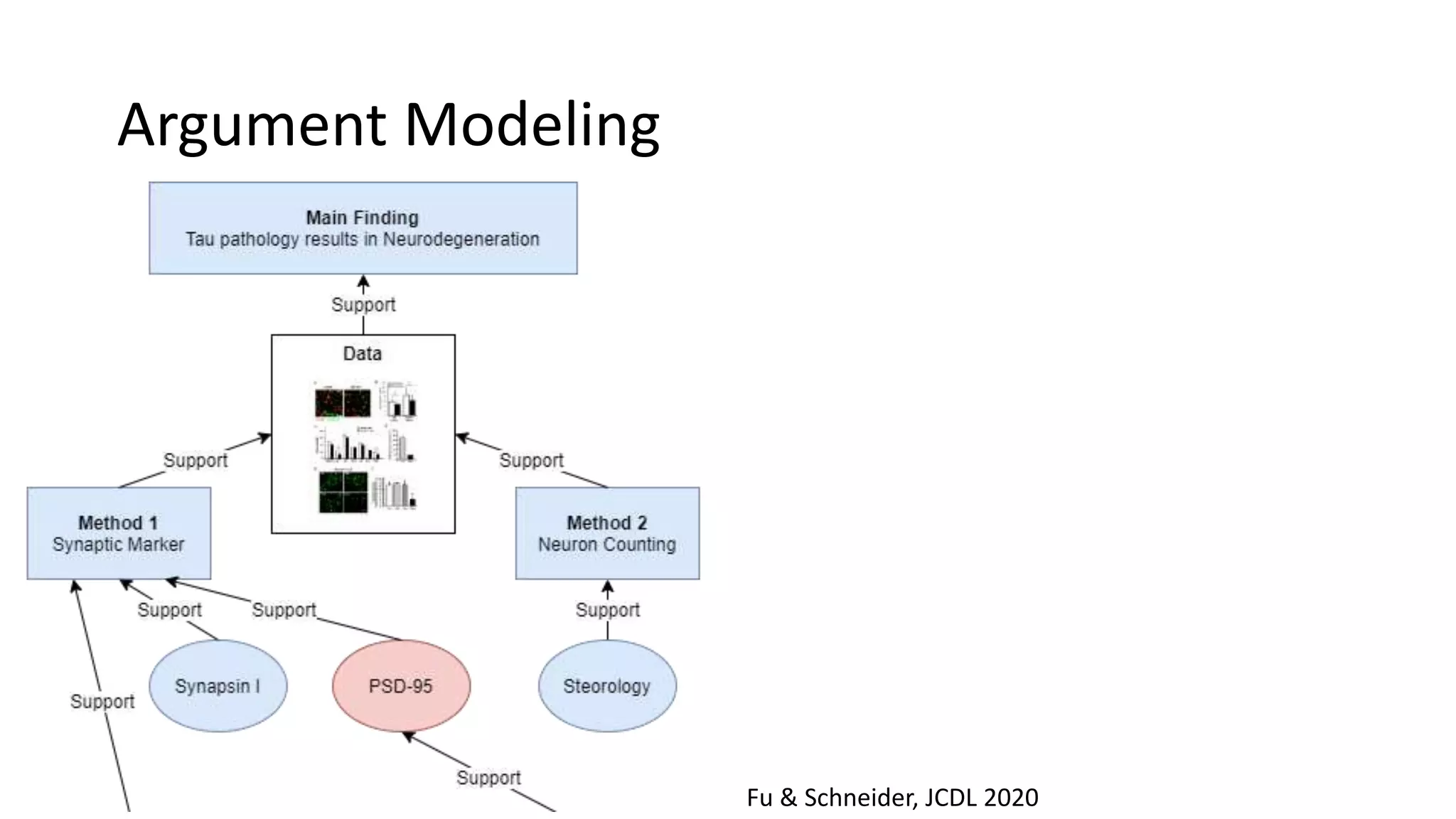

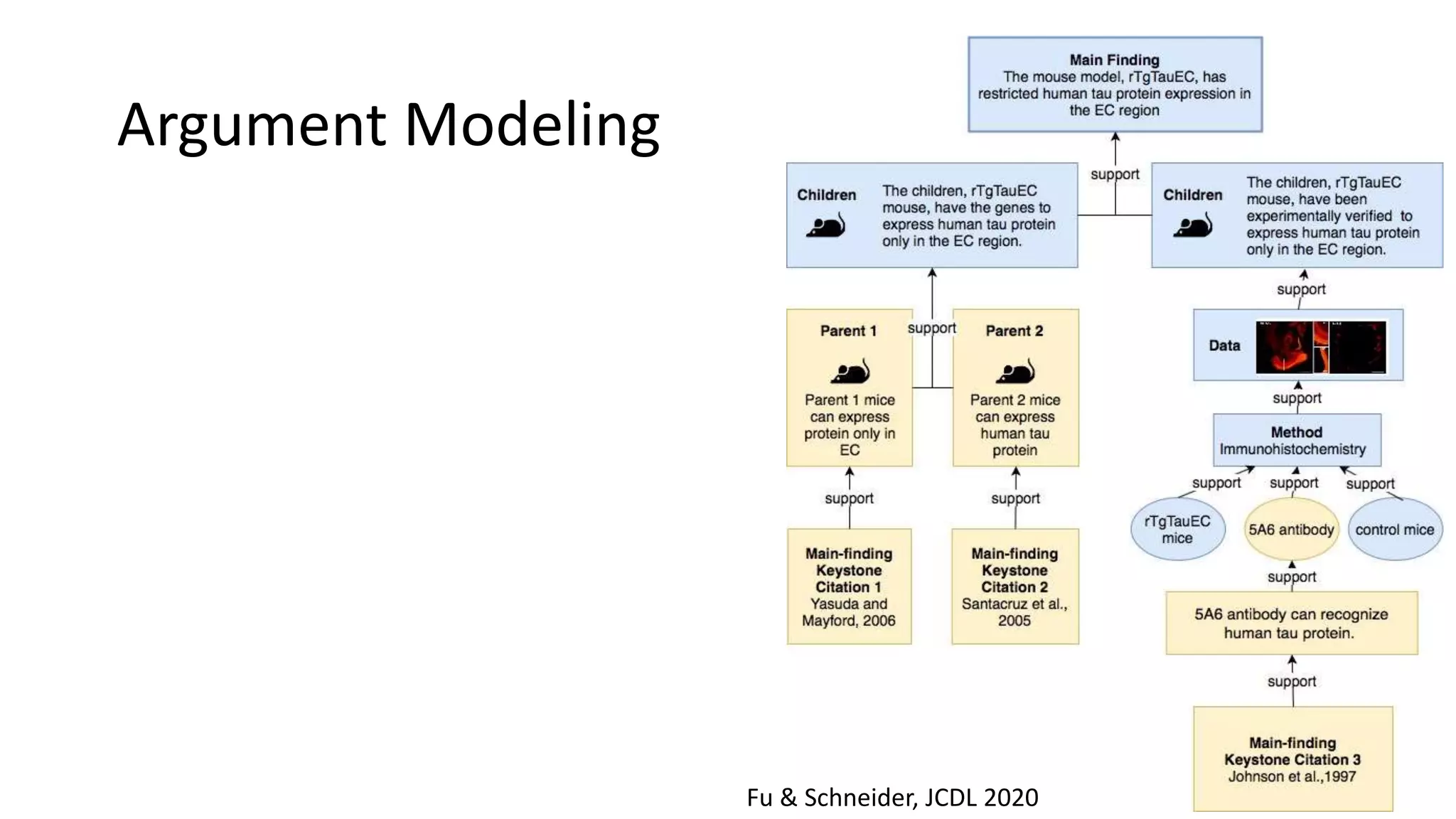

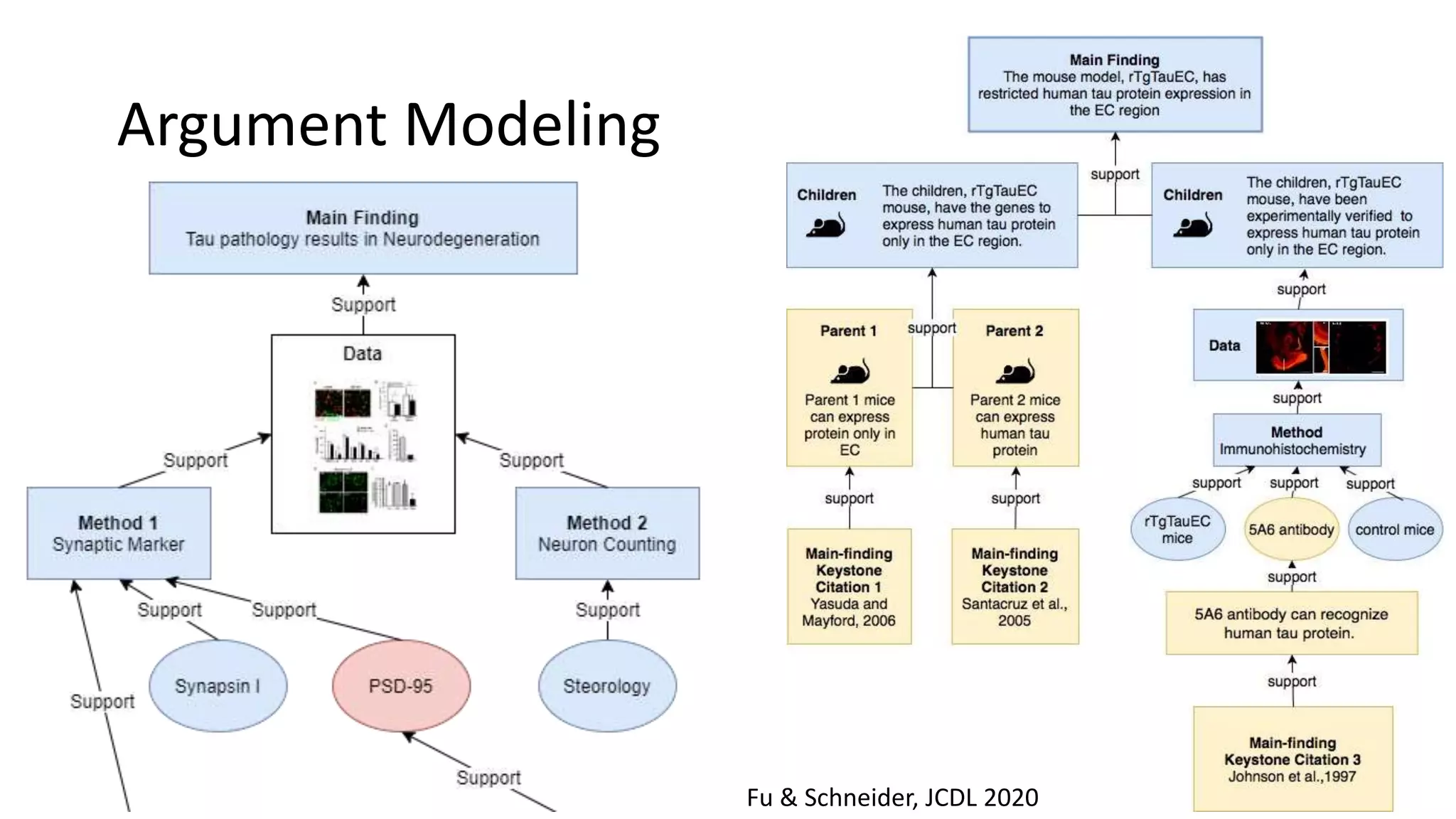

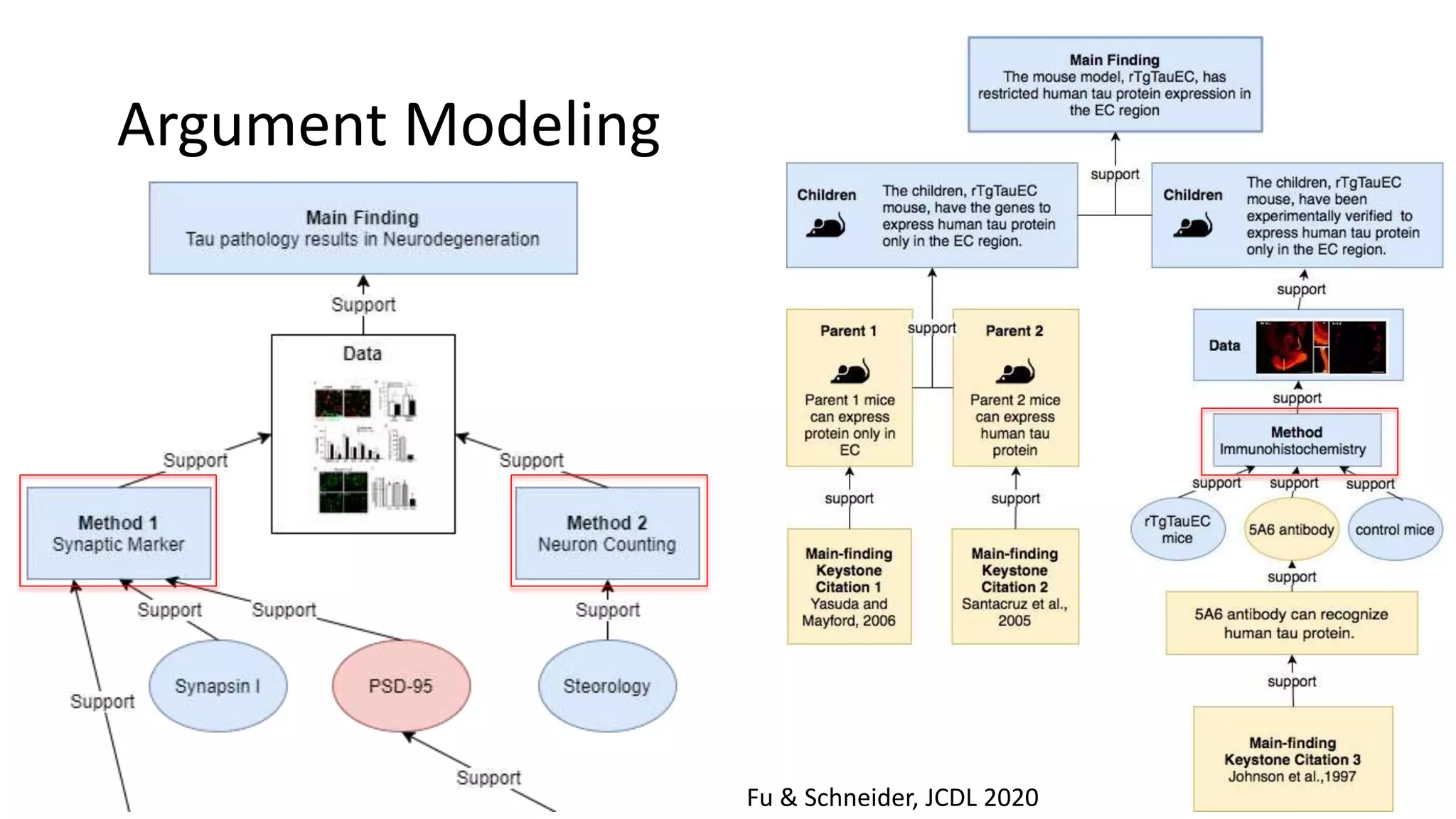

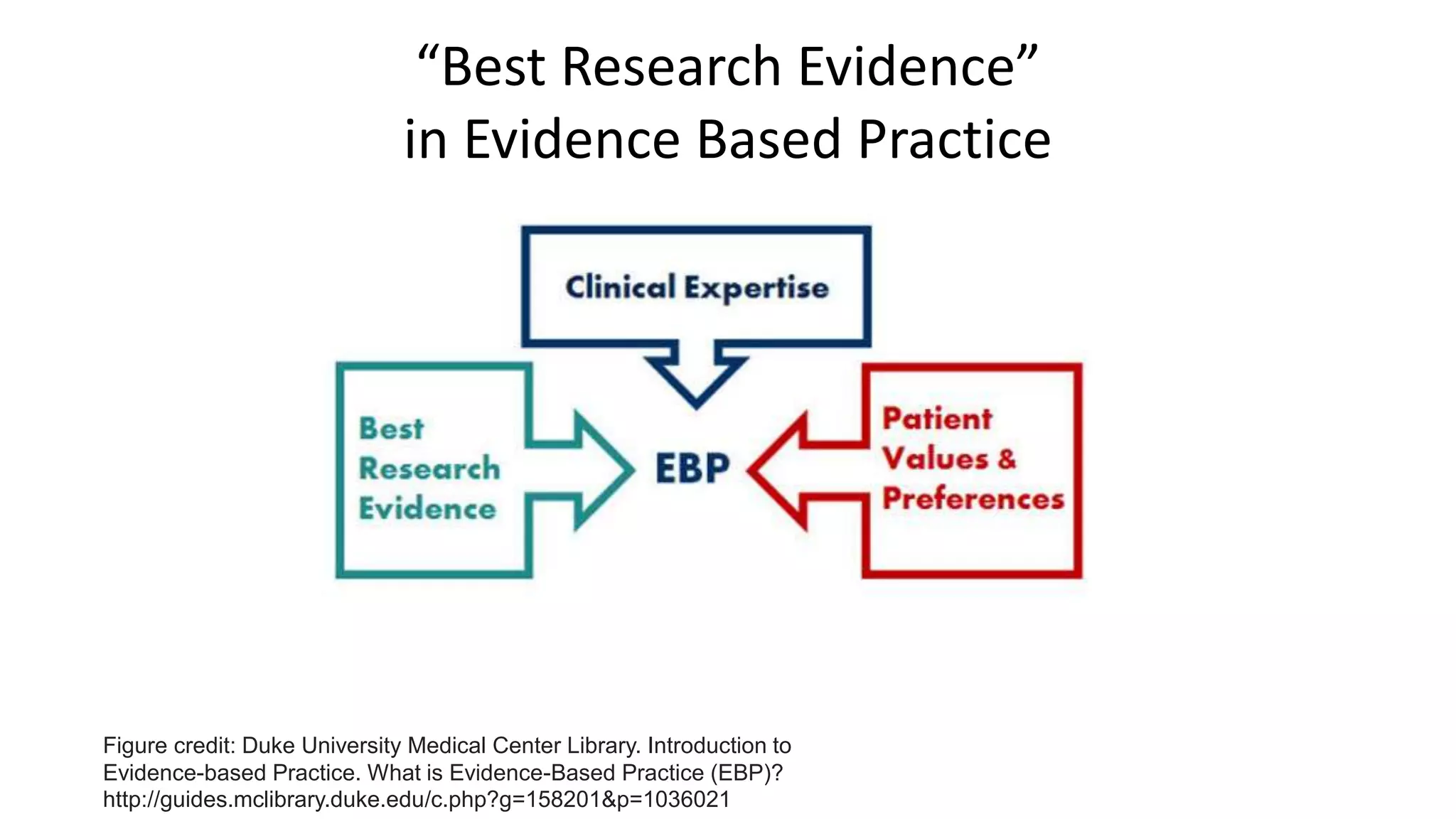

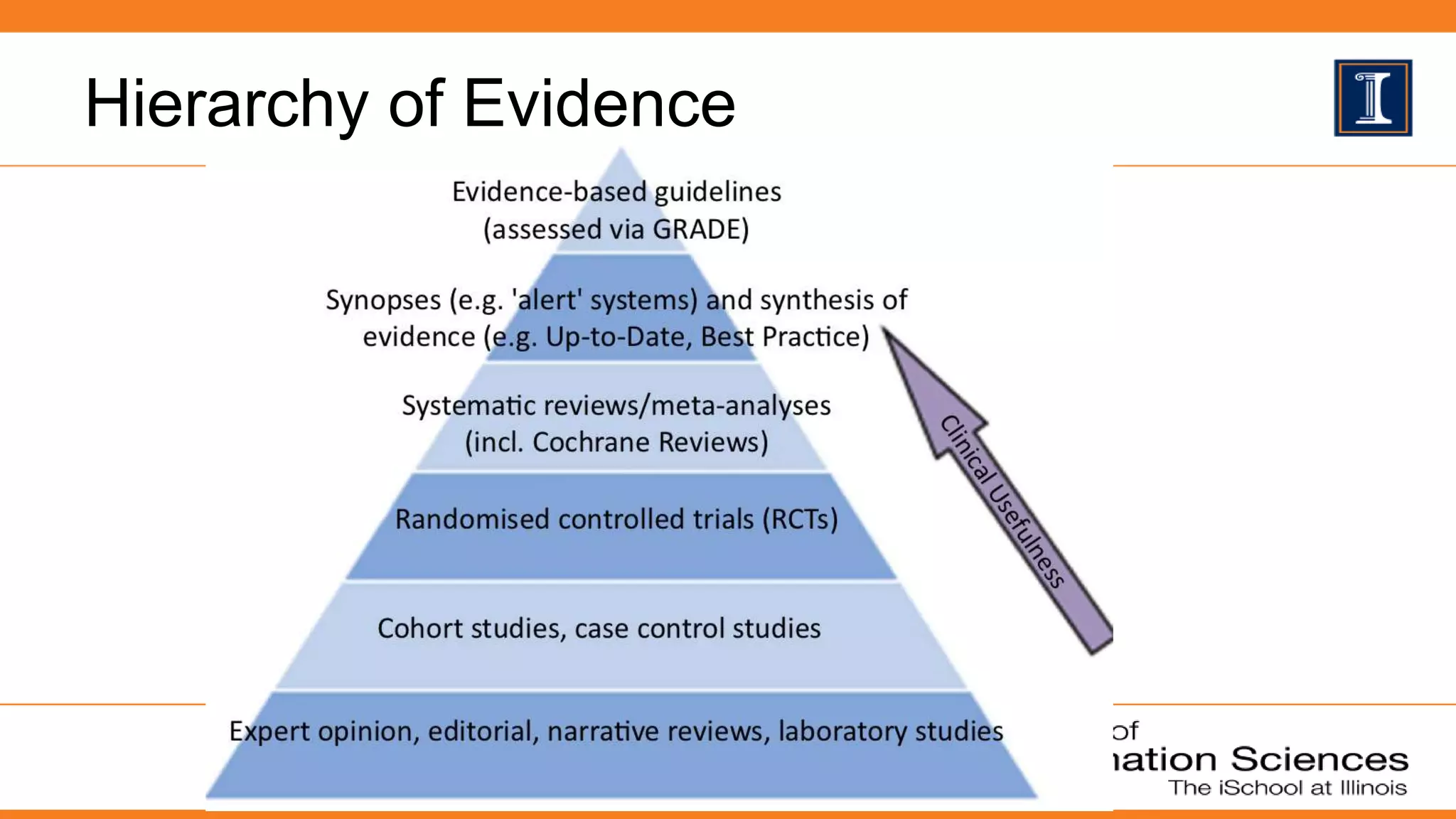

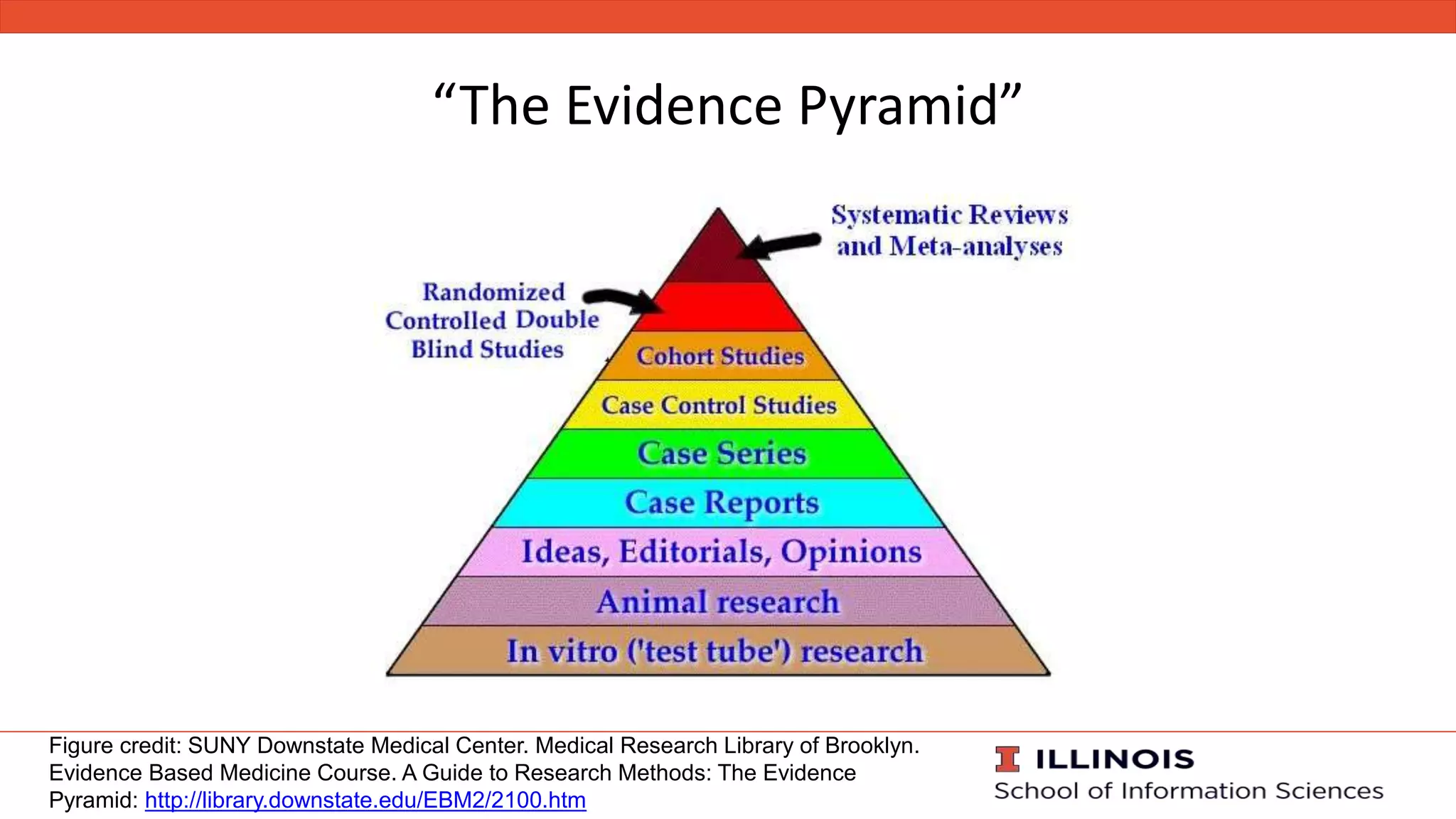

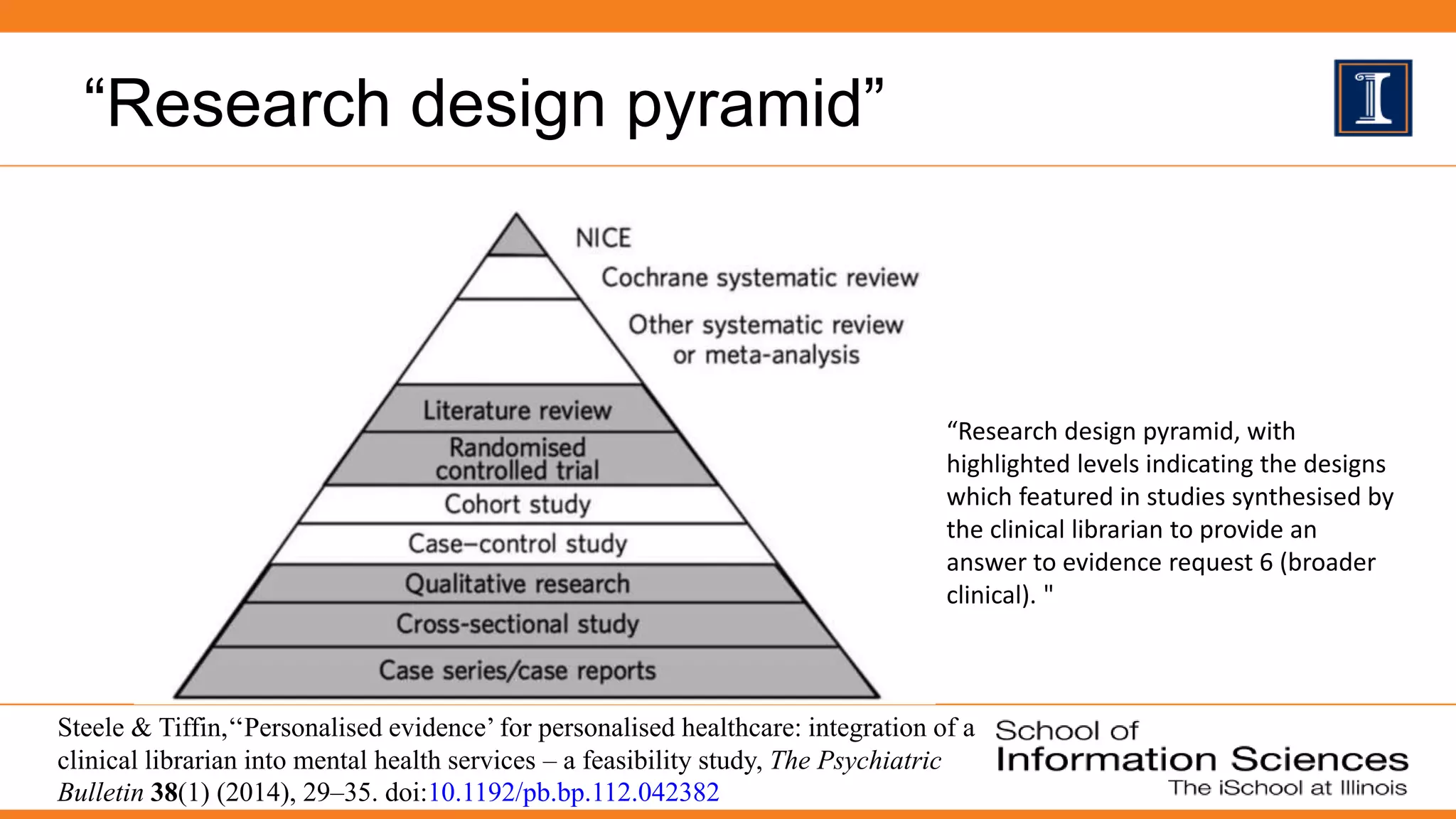

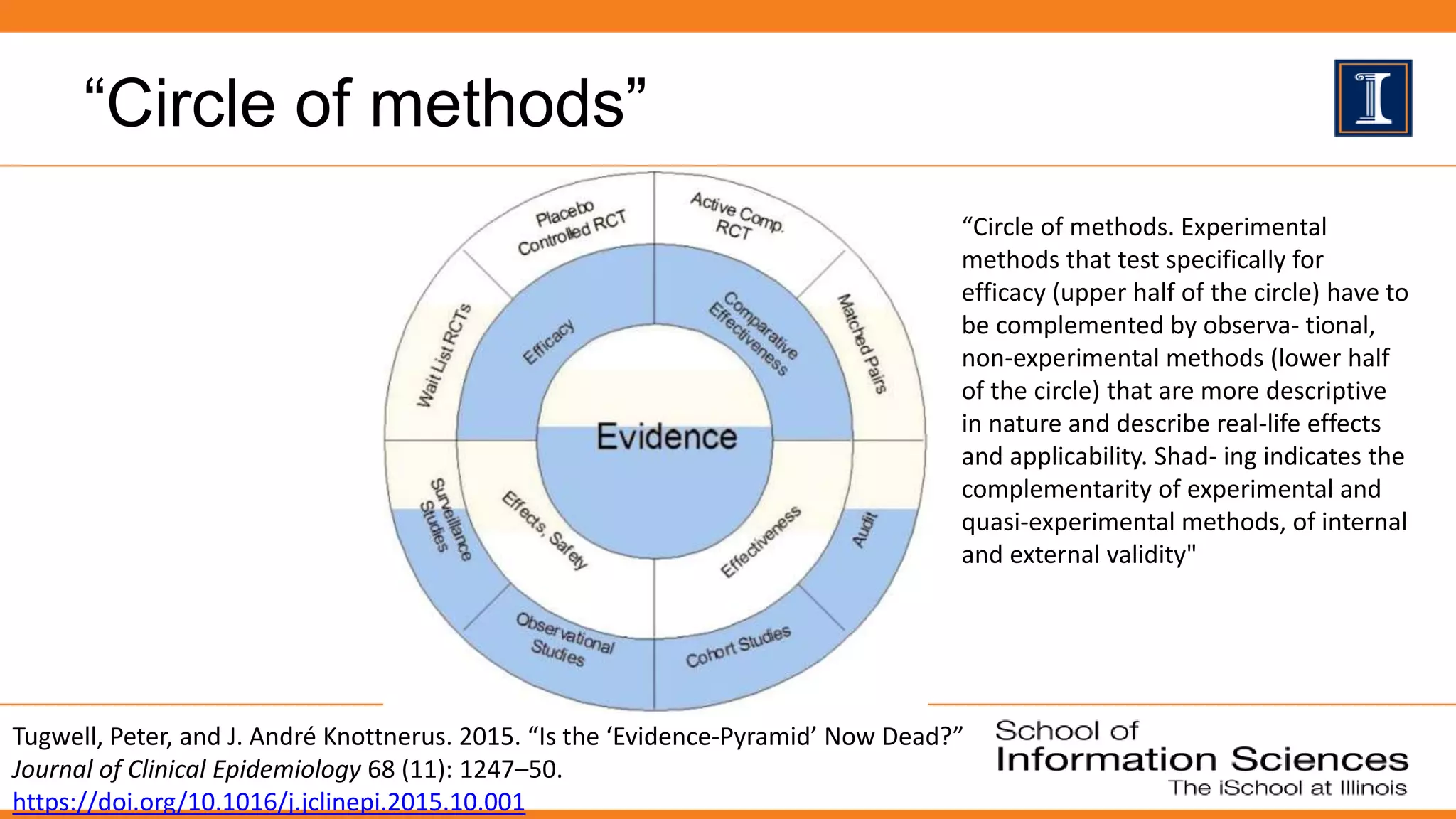

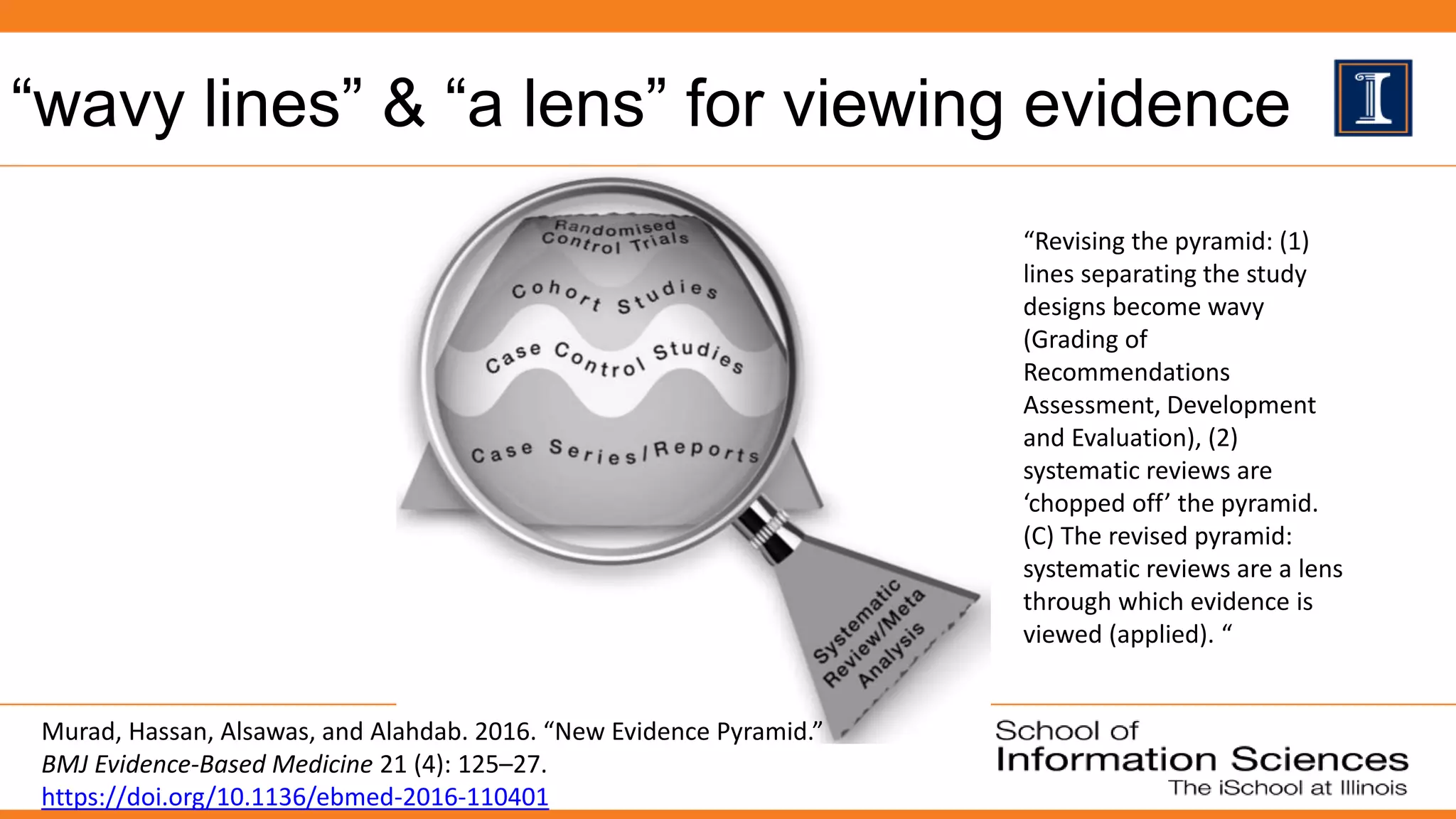

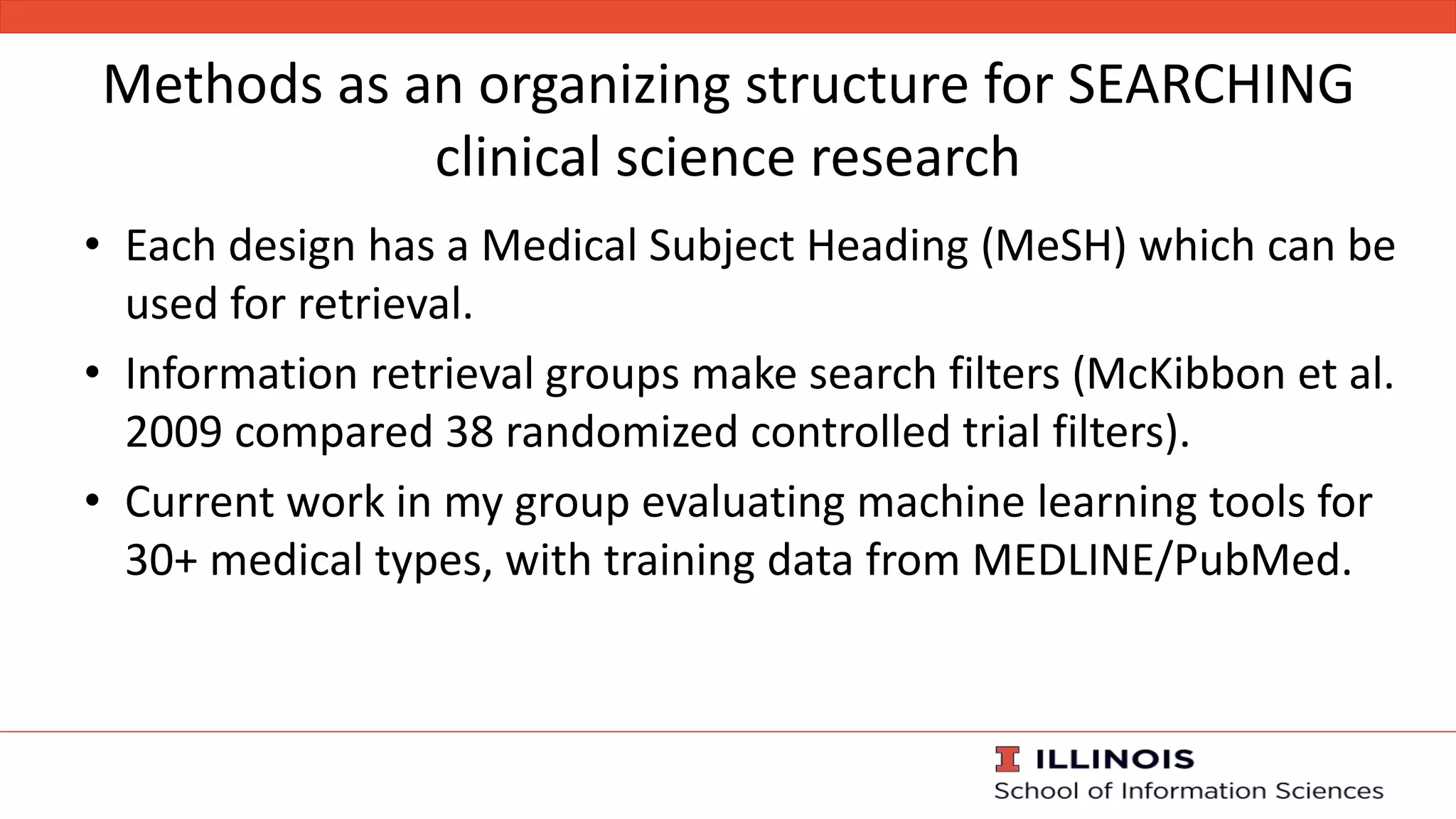

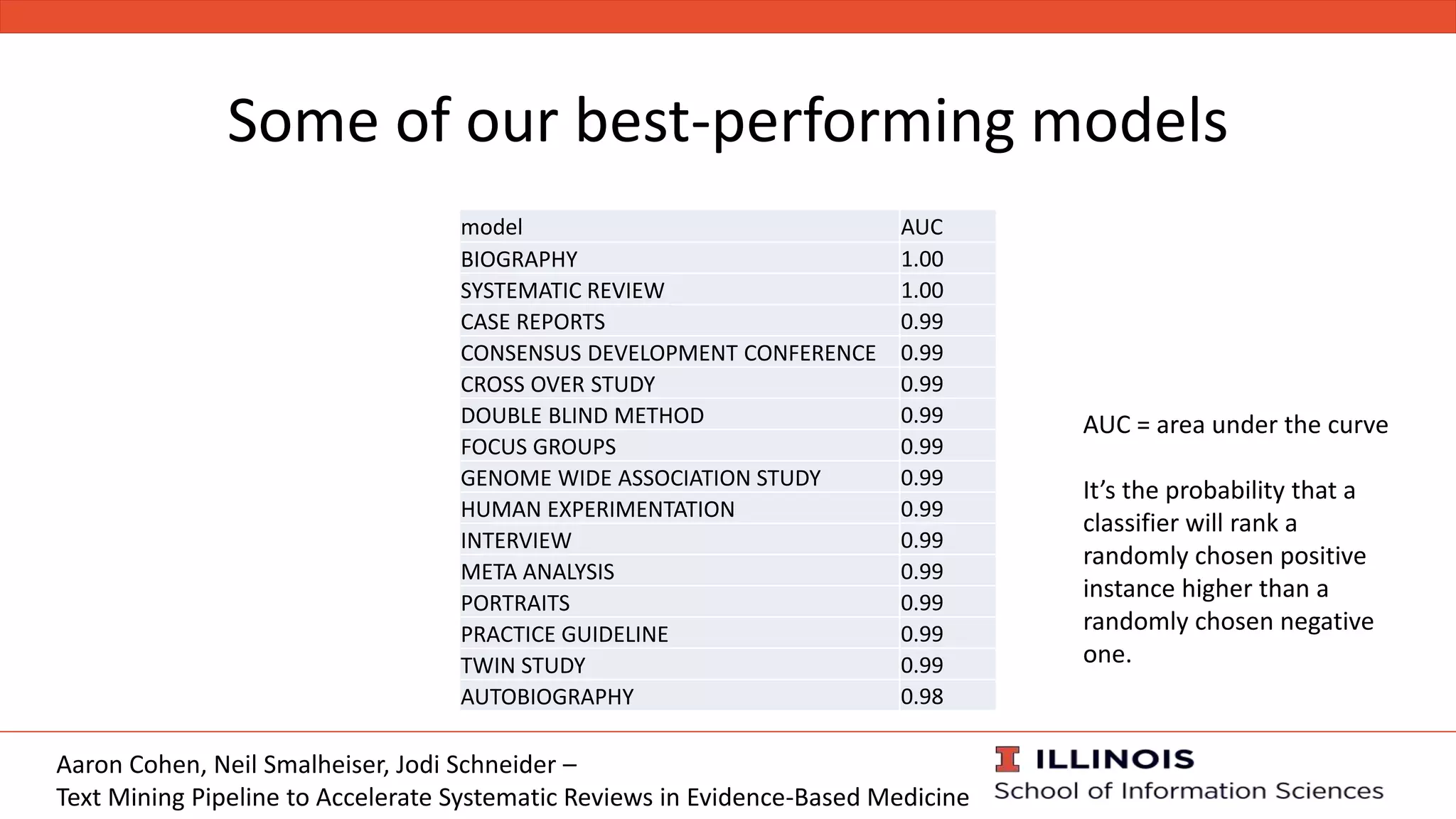

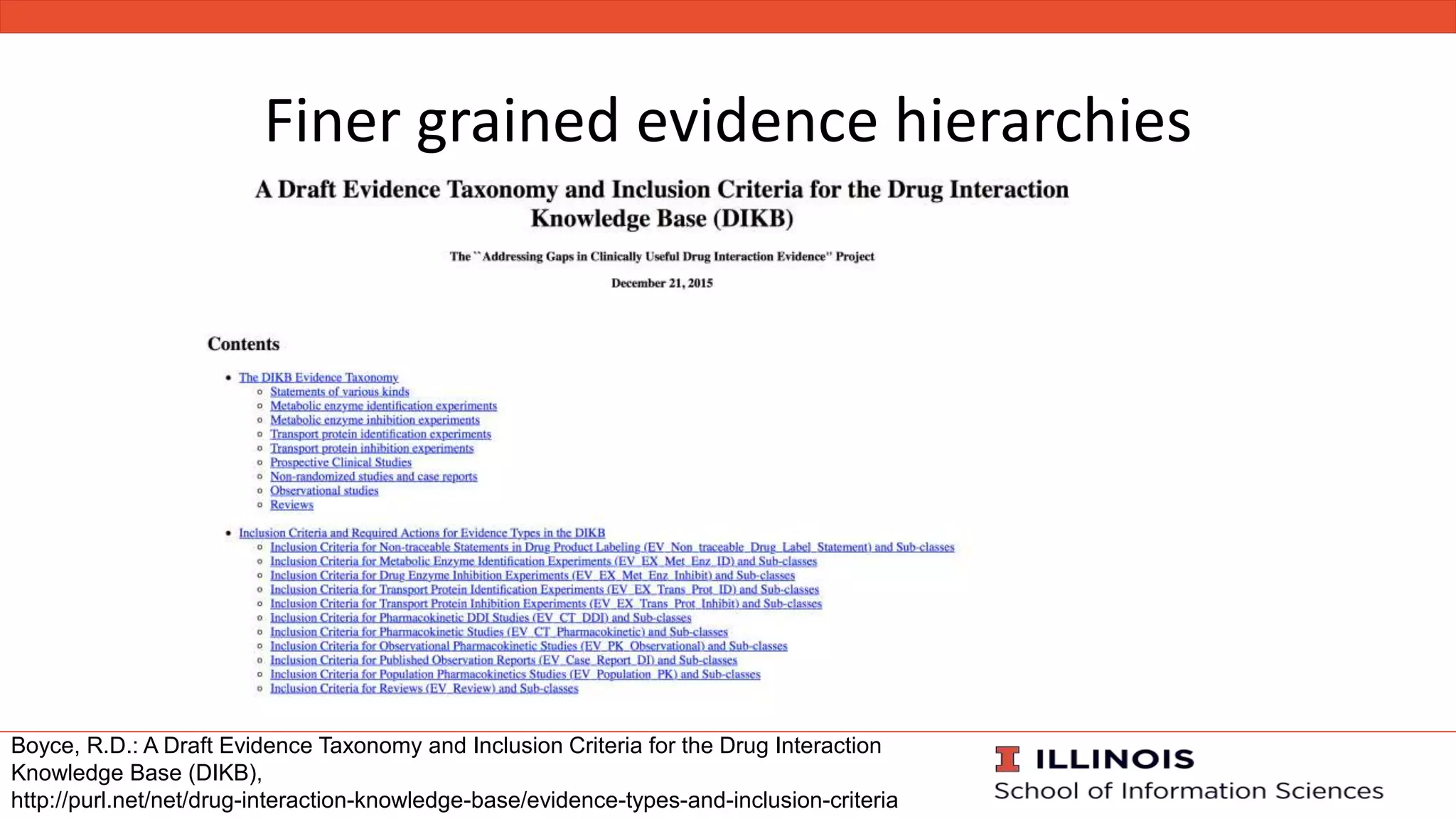

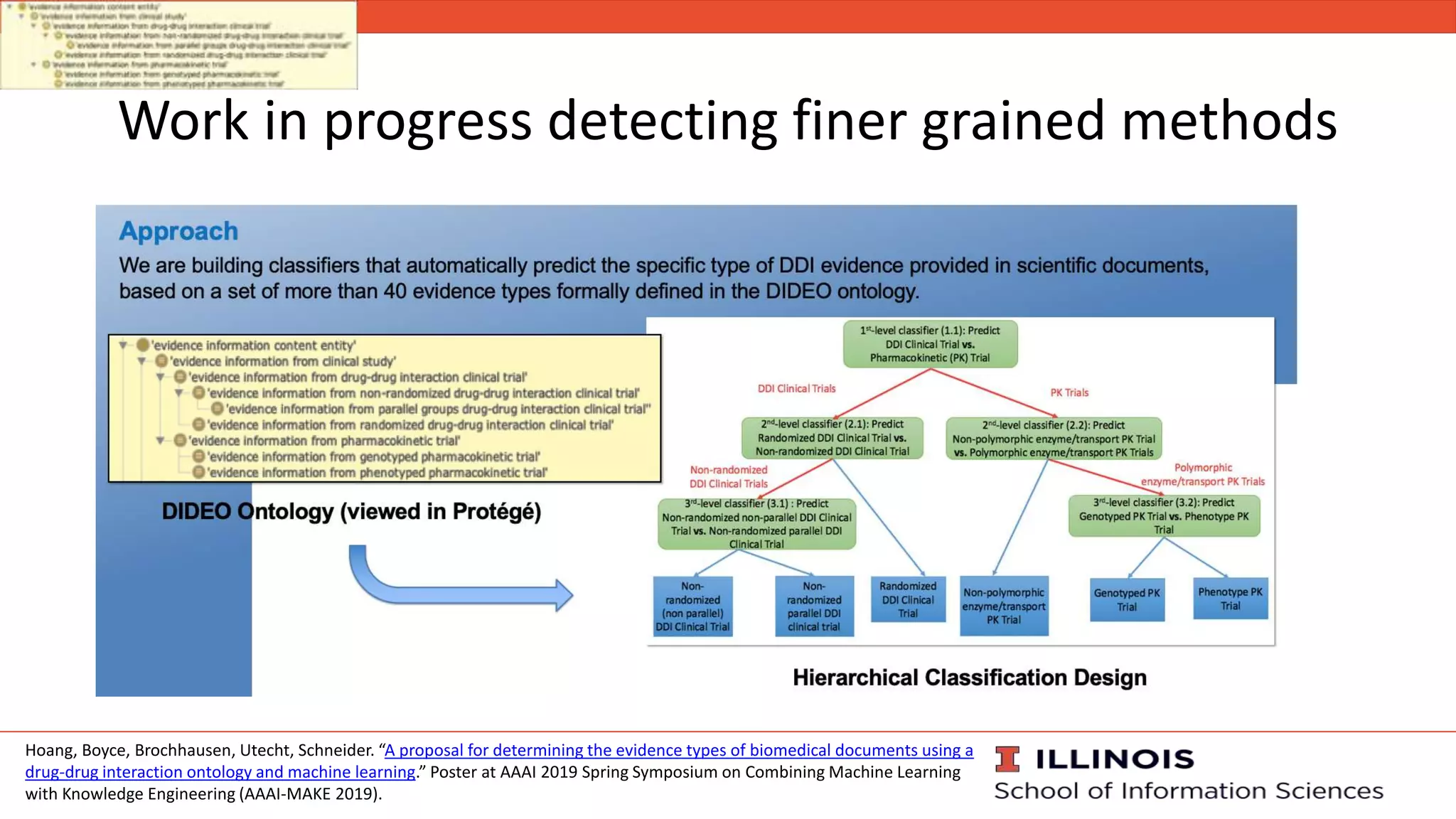

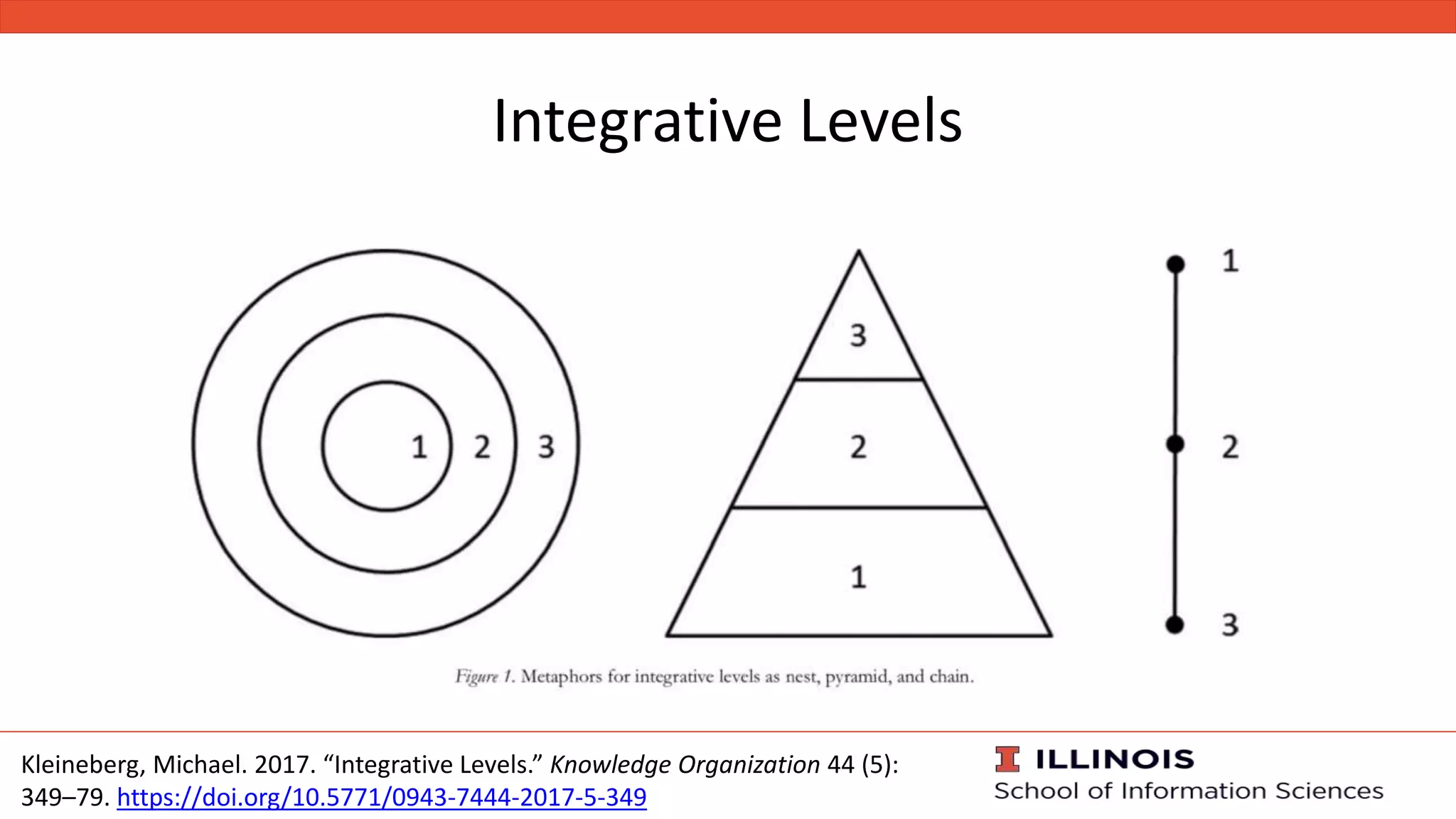

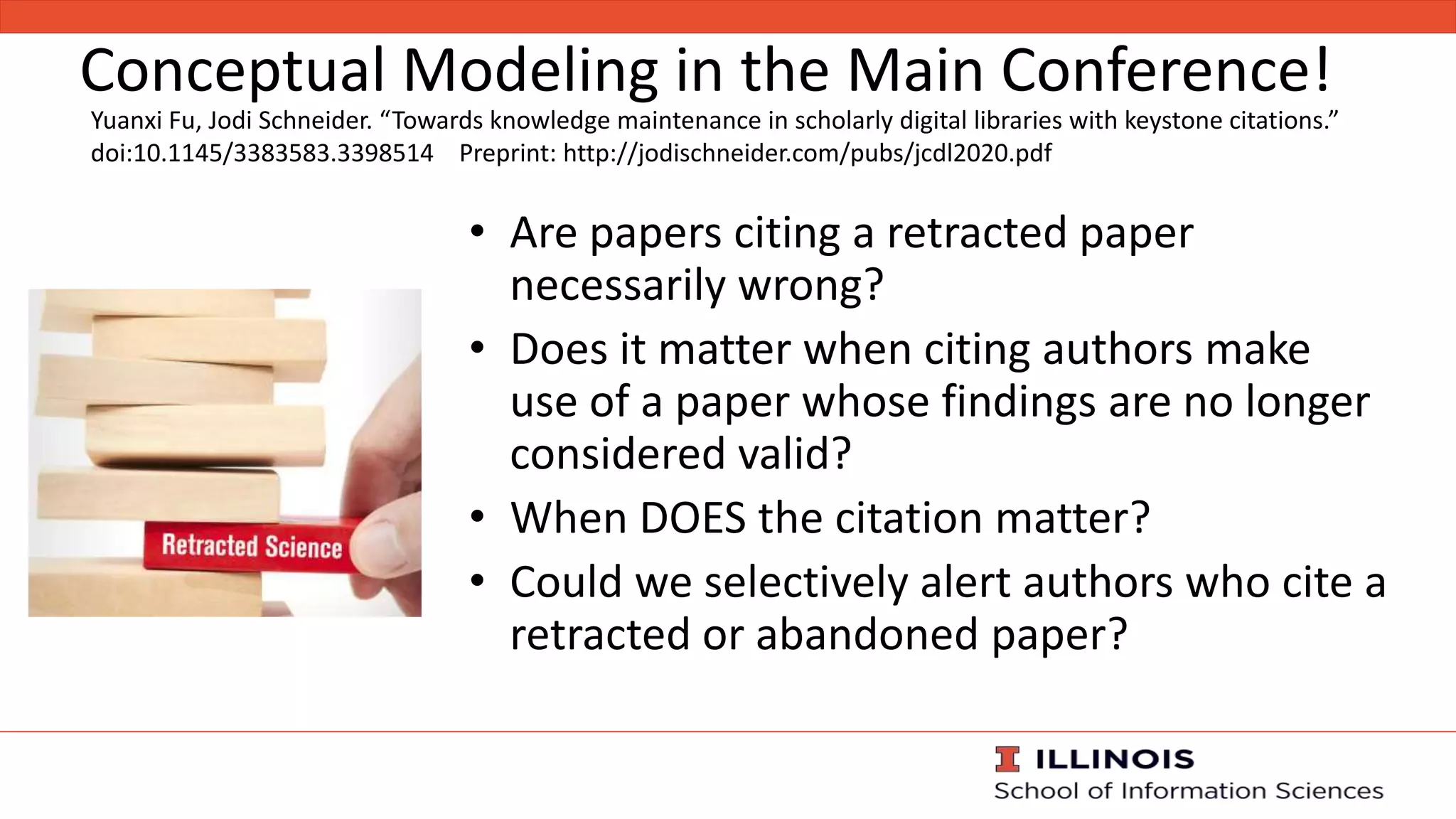

The document discusses the role of methods as a knowledge organizing structure in evidence-based medicine, emphasizing their importance in generating, reporting, and searching for clinical research evidence. It highlights the various hierarchies of evidence and the potential complications of traditional evidence pyramids. The document concludes by raising questions about citation practices concerning retracted papers and the influence of methods in validating scientific claims.

![Under our framework:

1) A scientific research paper puts forward at

least one main finding, along with a

logical argument, giving reasons and

evidence to support the main finding.

2) The main finding is accepted (or not) on

the basis of the logical argument.

3) Evidence from earlier literature may be

incorporated into the argument by citing a

paper and presenting it as support, using a

citation context.

Main Finding

Arguments

support

support

Data Methods Citations …

Citing ArticleCited Article

Citation Context

“Many papers with

known validity problems

are highly cited [3].”

Our

paper

[3] = Bar-Ilan, J.

and Halevi, G.

2018. Temporal

characteristics

of retracted

articles](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/methods-pyramids-sigcm-atjcdl2020-2020-08-01-200801225004/75/Methods-Pyramids-as-an-Organizing-Structure-for-Evidence-Based-Medicine-SIGCM-at-JCDL2020-2020-08-01-34-2048.jpg)