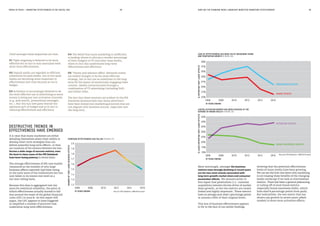

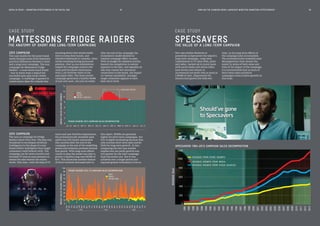

This document summarizes key findings from a study of the IPA Databank on marketing effectiveness in the digital era. Some of the main points include:

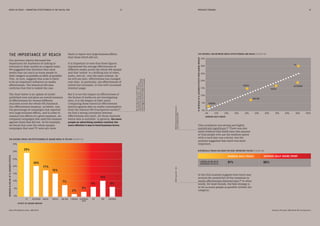

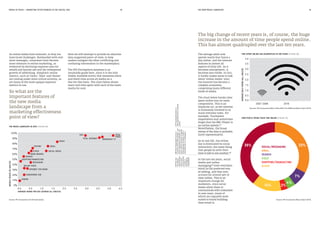

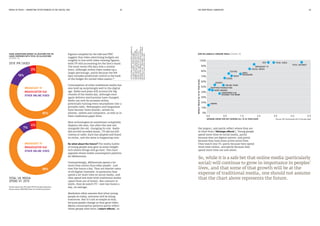

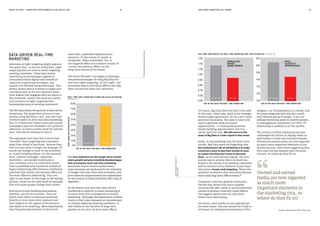

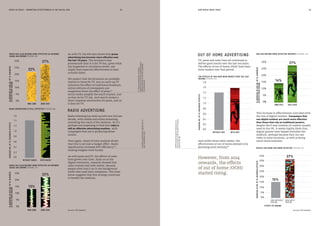

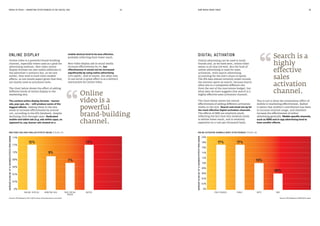

- Mass marketing and broad-reach campaigns are still effective at driving market share growth, which is a key driver of profit. The digital revolution has increased the potential effectiveness of most marketing forms, including traditional media.

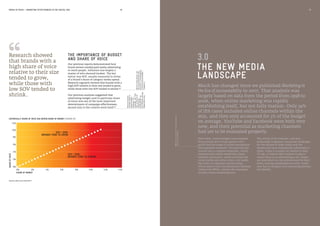

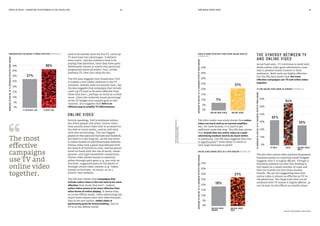

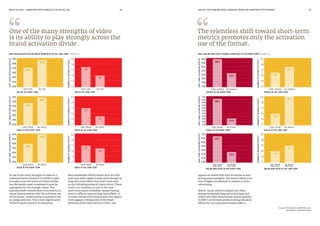

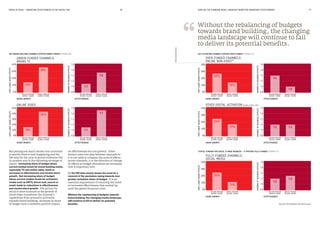

- A balance of long-term brand building (around 60% of spend) and short-term activation (around 40% of spend) is still the best strategy. Video advertising, both online and offline, is the most effective brand-building format, while paid search and email emerge as the most effective activation channels.

- However,