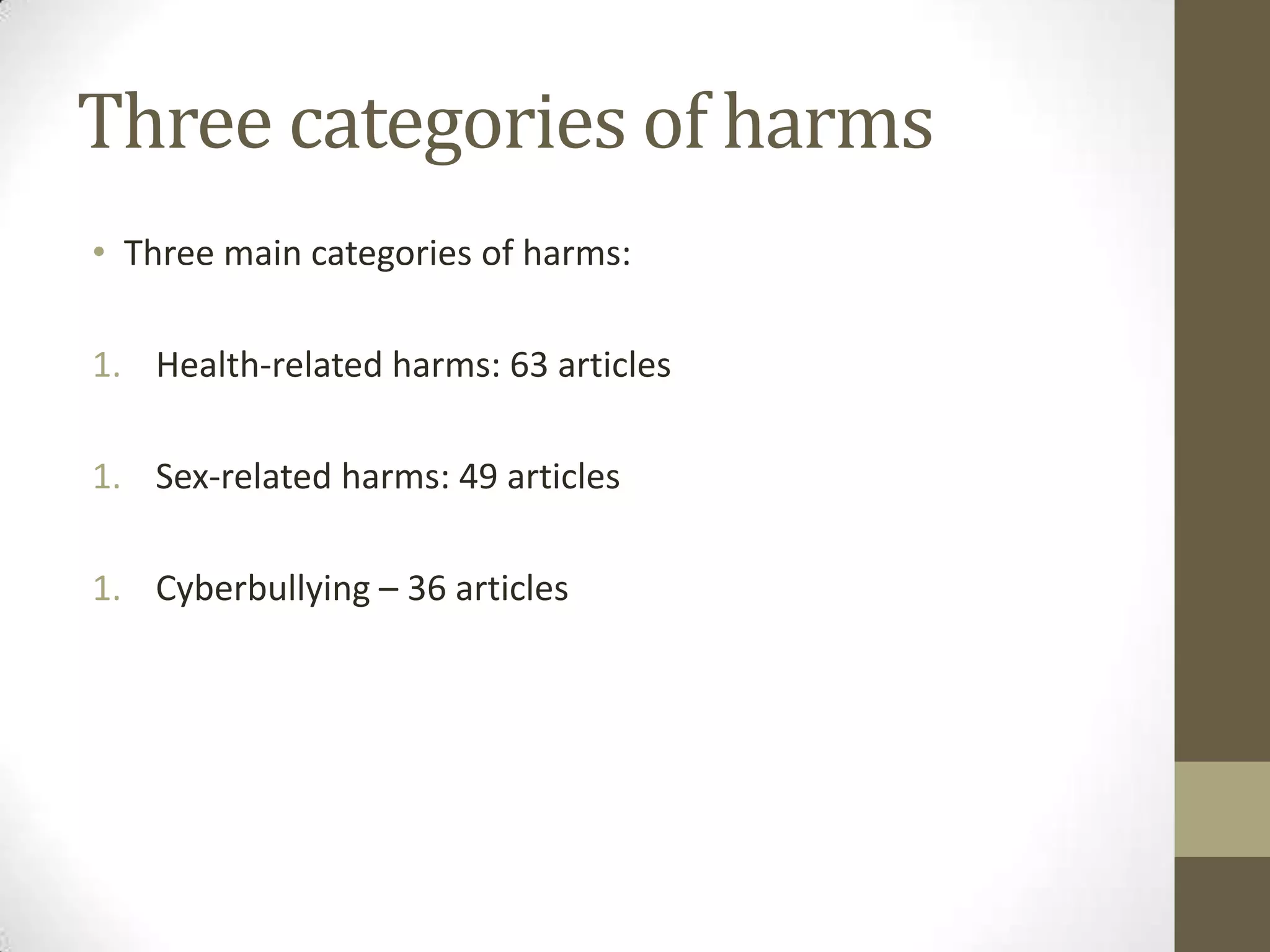

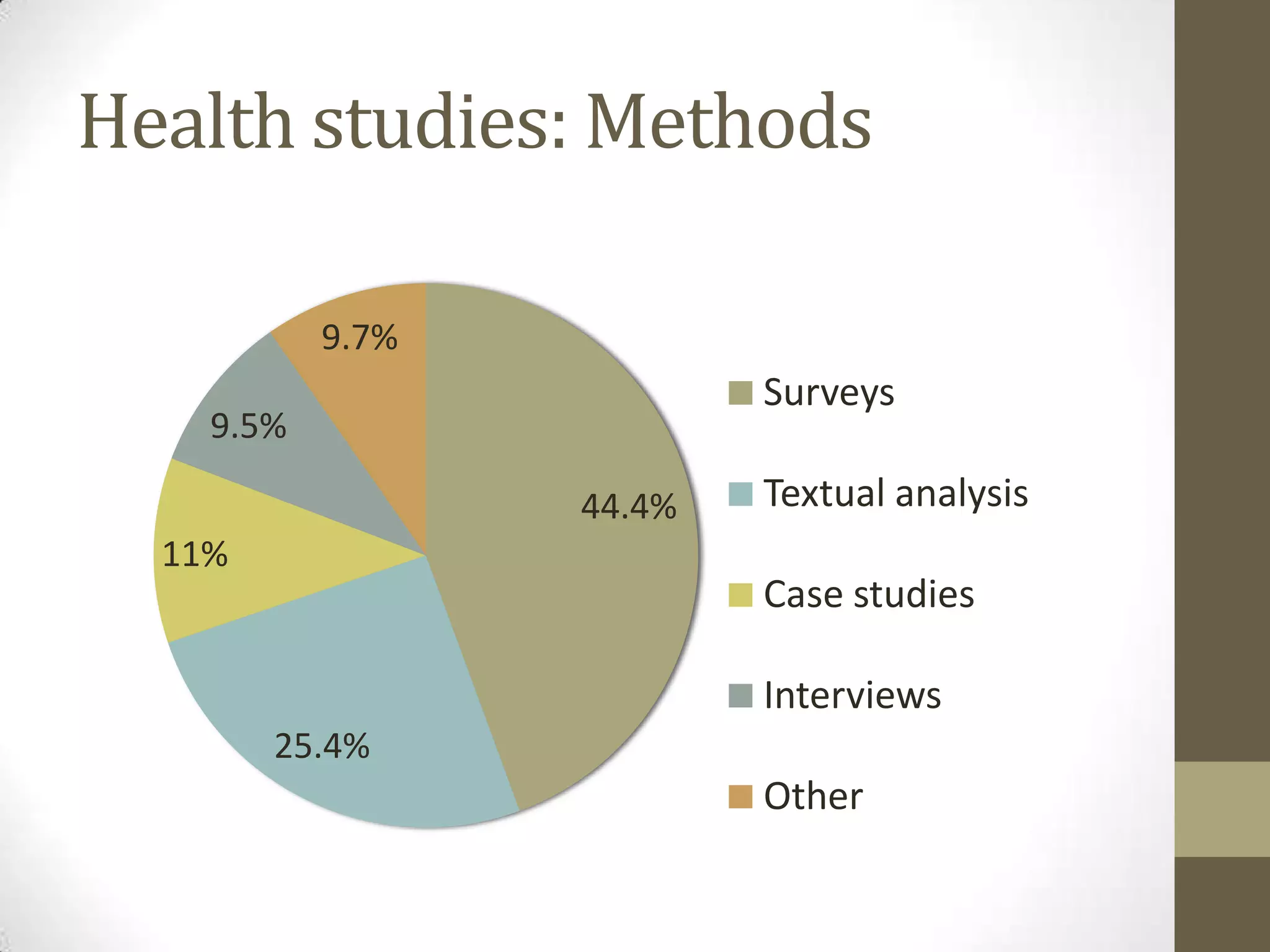

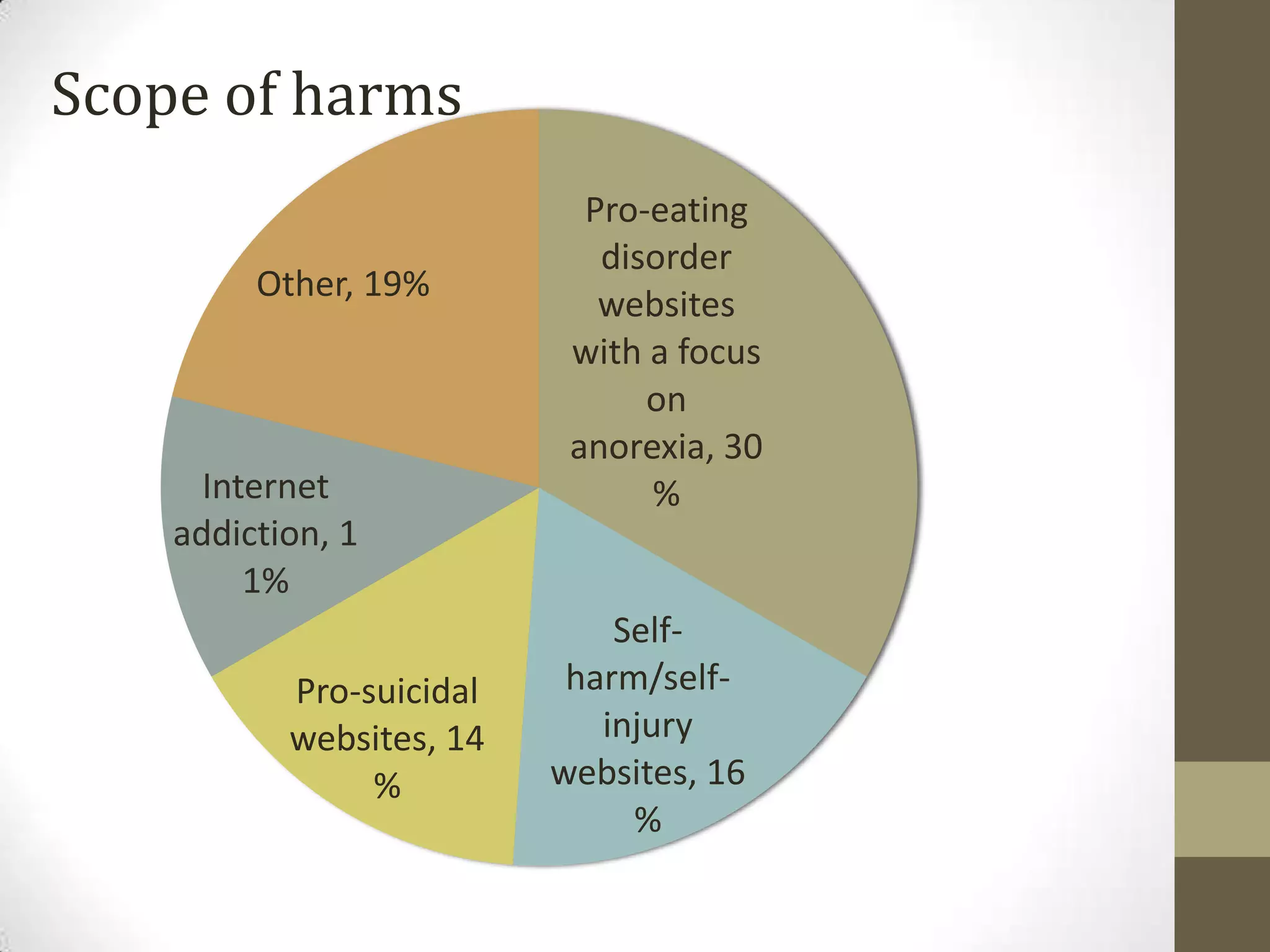

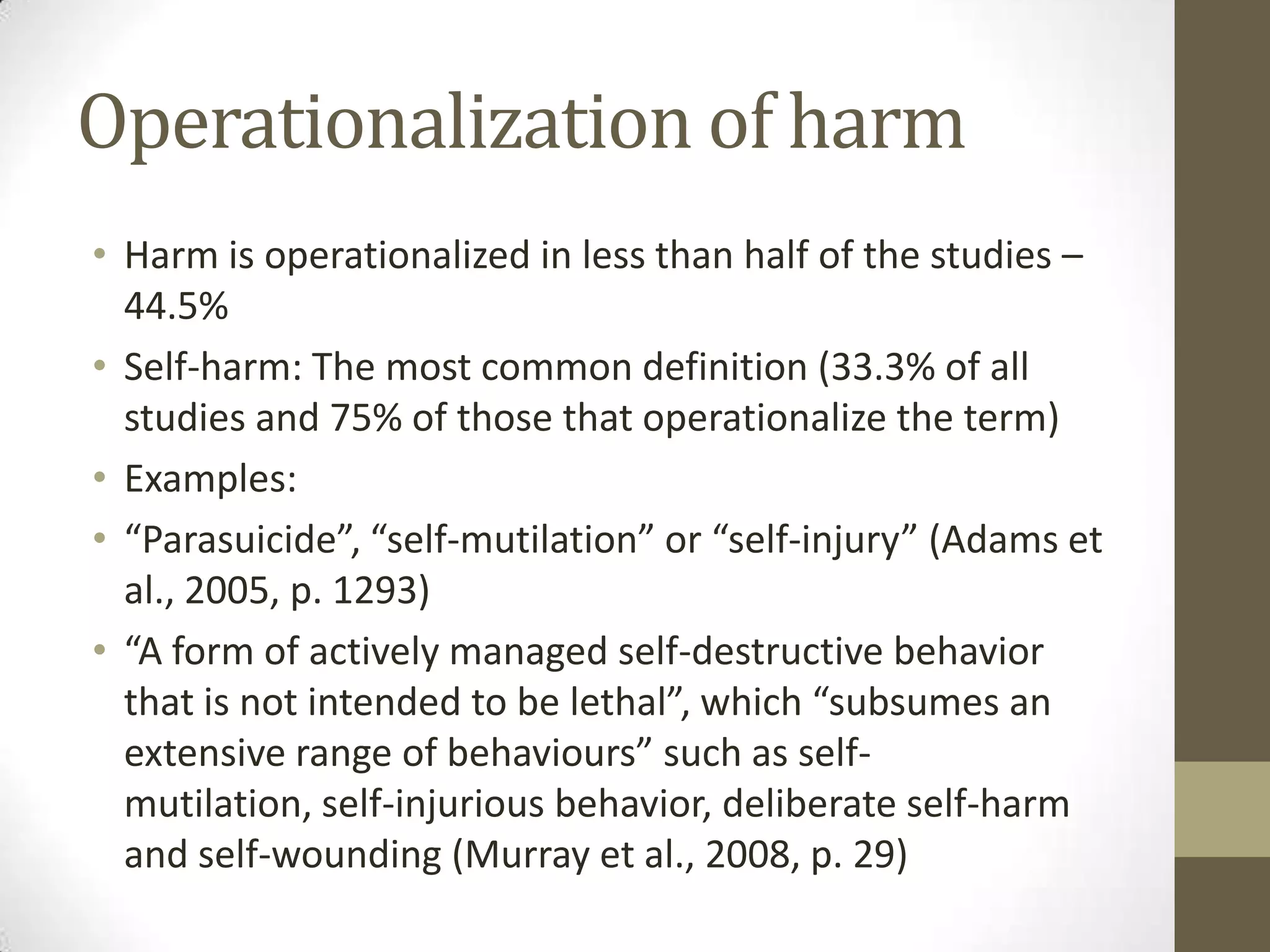

The document summarizes research on whether the internet harms children's health. It finds that while some children experience real health harms from online risks, like encouragement of suicide or eating disorders, the evidence for widespread or low-risk harms is limited. Studies often rely on surveys that show potential harms and risks but provide little data on actual harms experienced. More research is still needed, especially on whether behaviors like viewing pro-eating disorder websites cause harm. In conclusion, some children are harmed, but the level of harm across all children is unclear from current research.