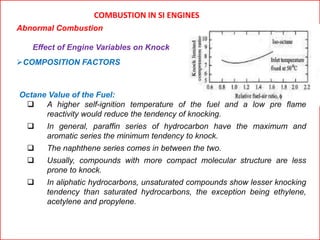

This document outlines the syllabus for an Advanced Internal Combustion Engines course. The syllabus covers 5 units: 1) Spark Ignition Engines, 2) Compression Ignition Engines, 3) Pollutant Formation and Control, 4) Alternative Fuels, and 5) Recent Trends. Some key topics include fuel injection systems, combustion processes, knock, emissions, and alternative fuels like ethanol and natural gas. The objectives are to understand IC engine operations and components and to evaluate pollutant formation, control, and alternative fuels. Upon completing the course, students will be able to compare IC engine types and components and assess pollution issues.