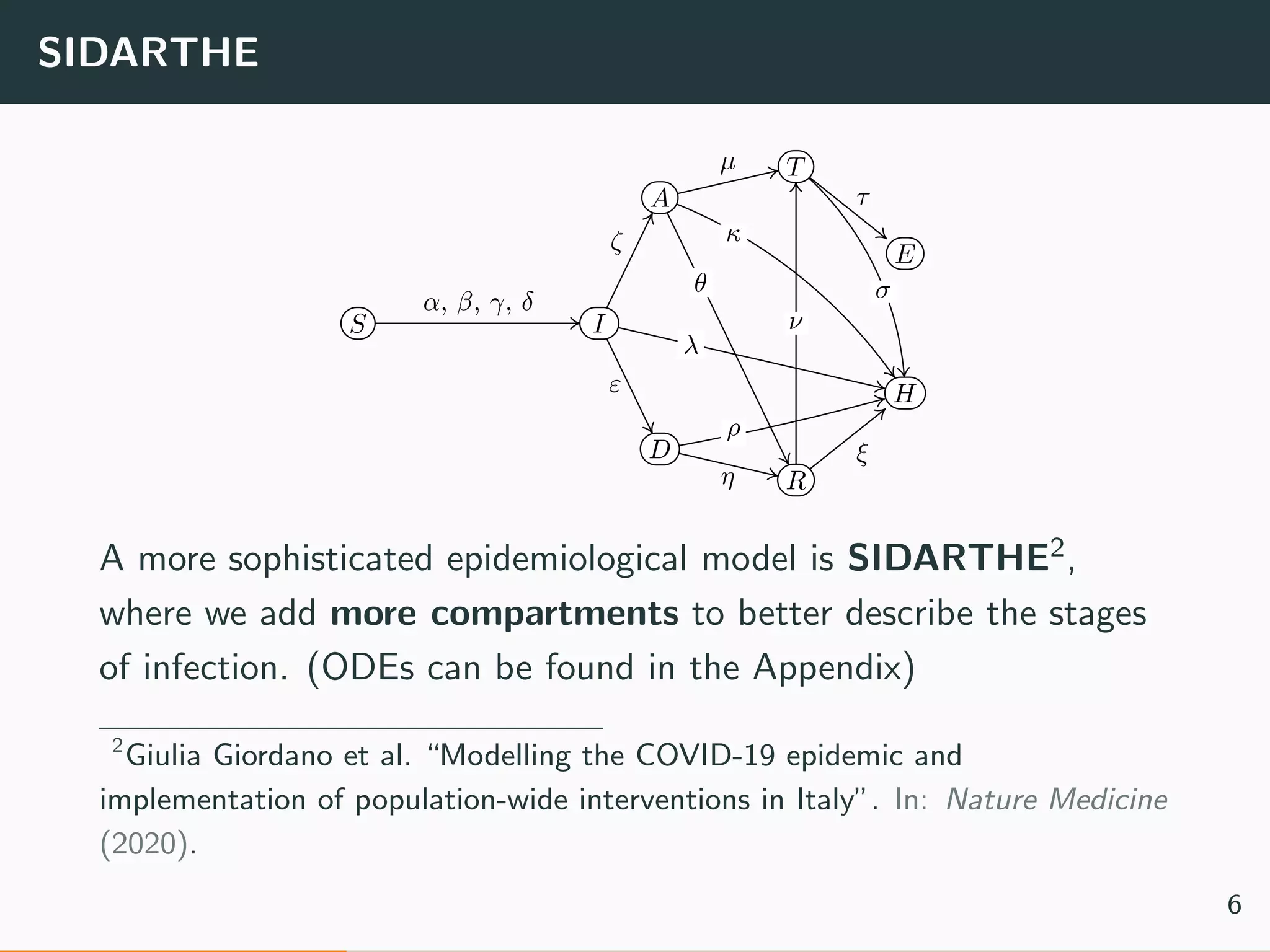

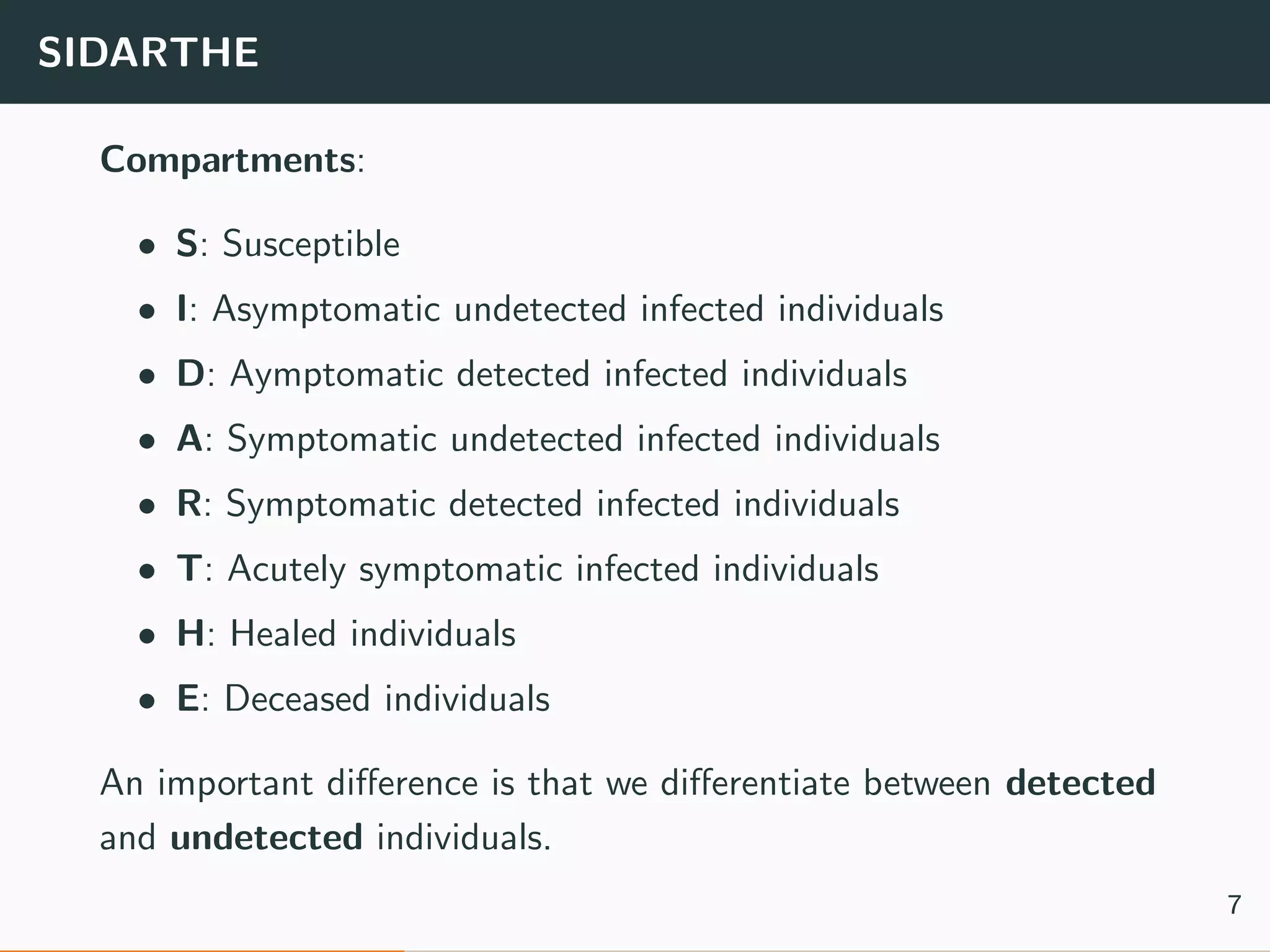

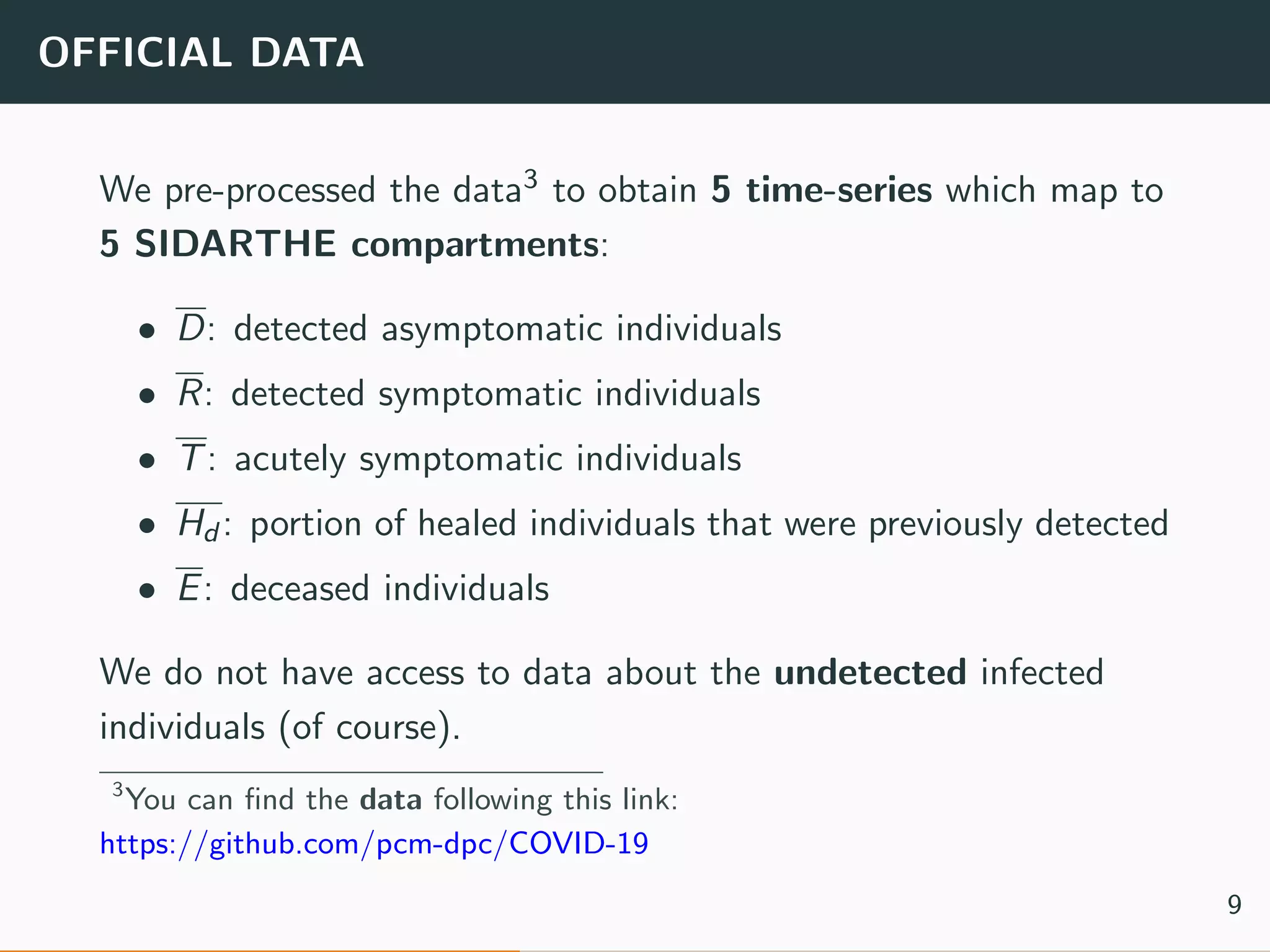

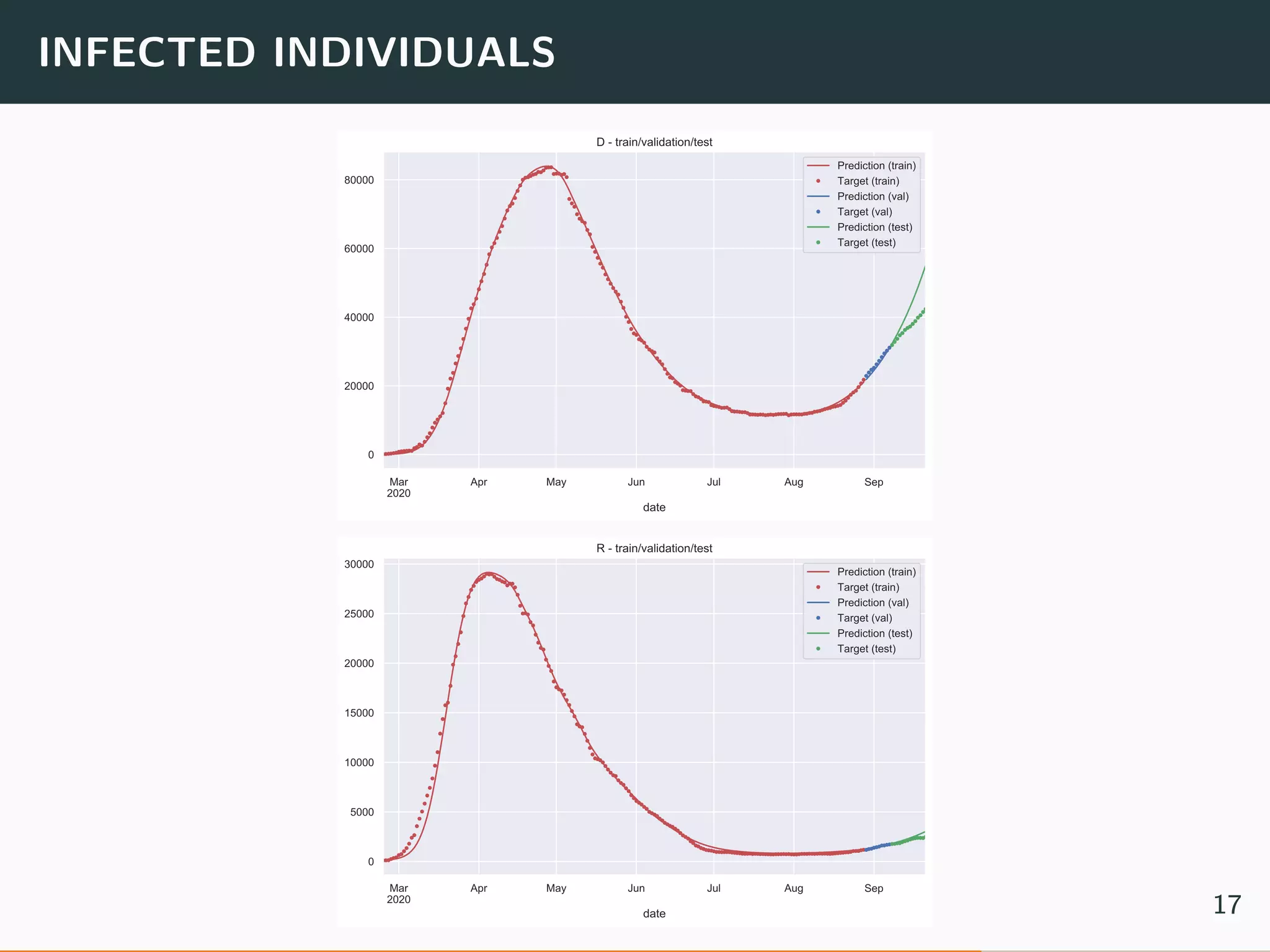

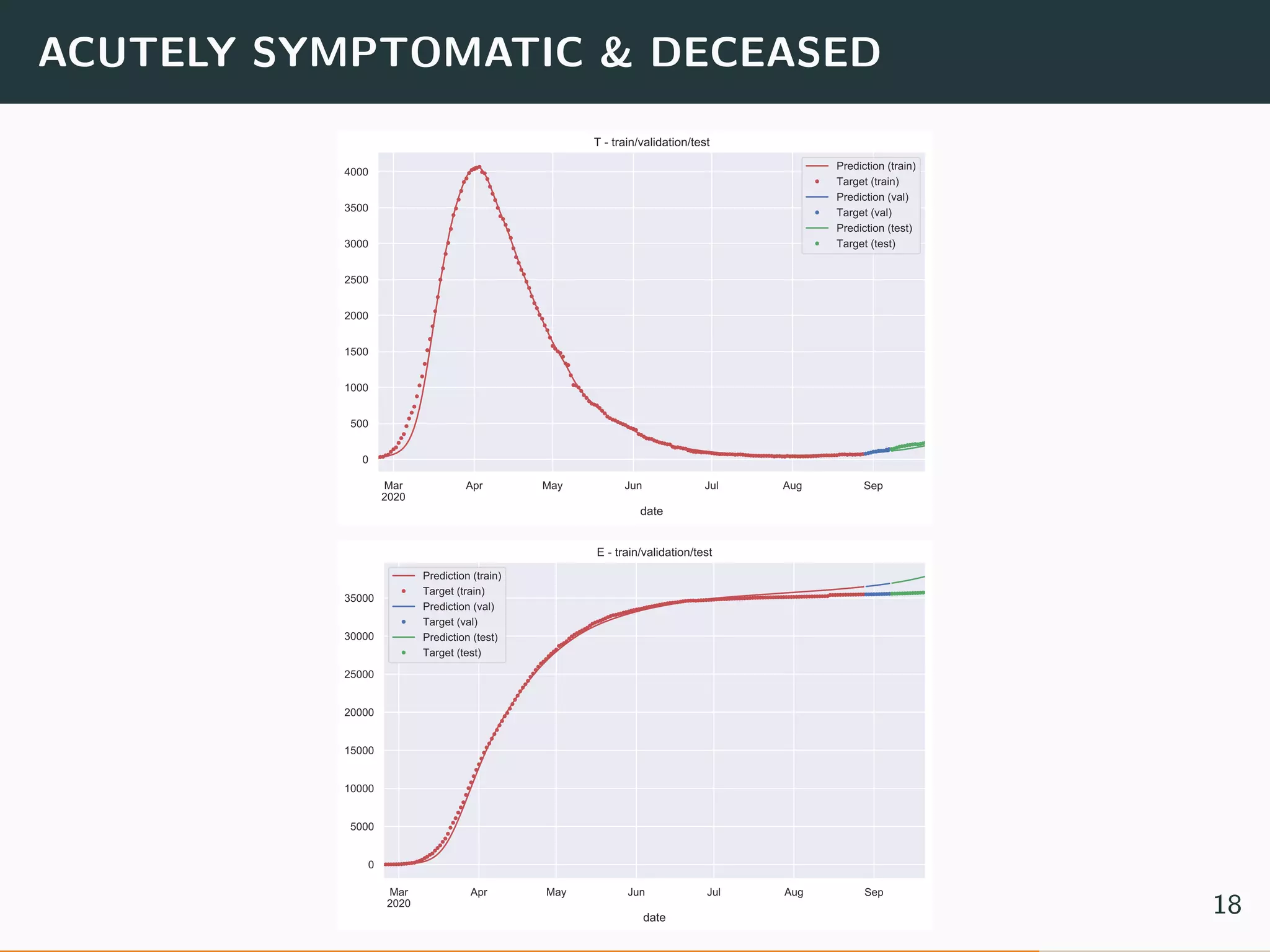

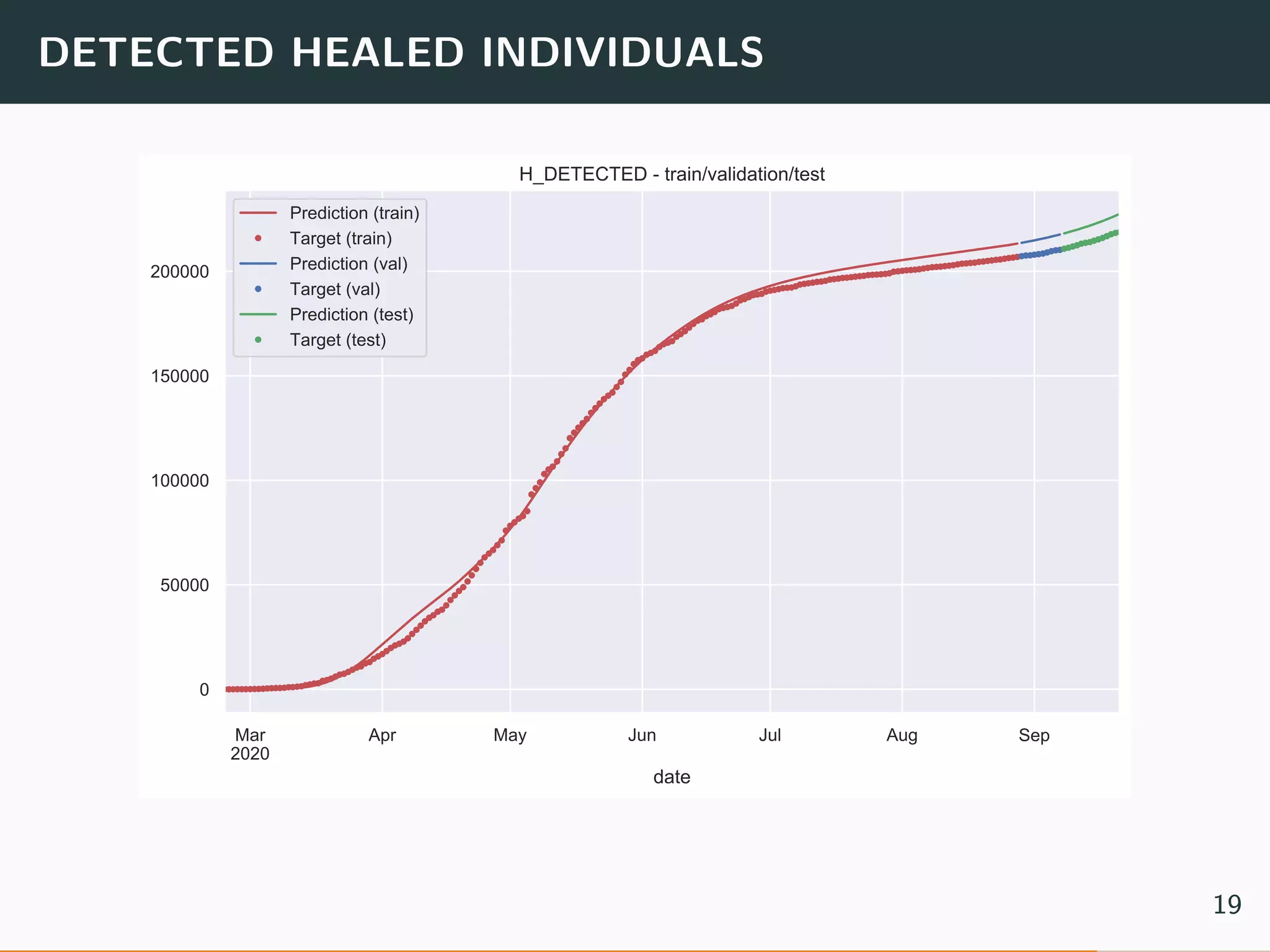

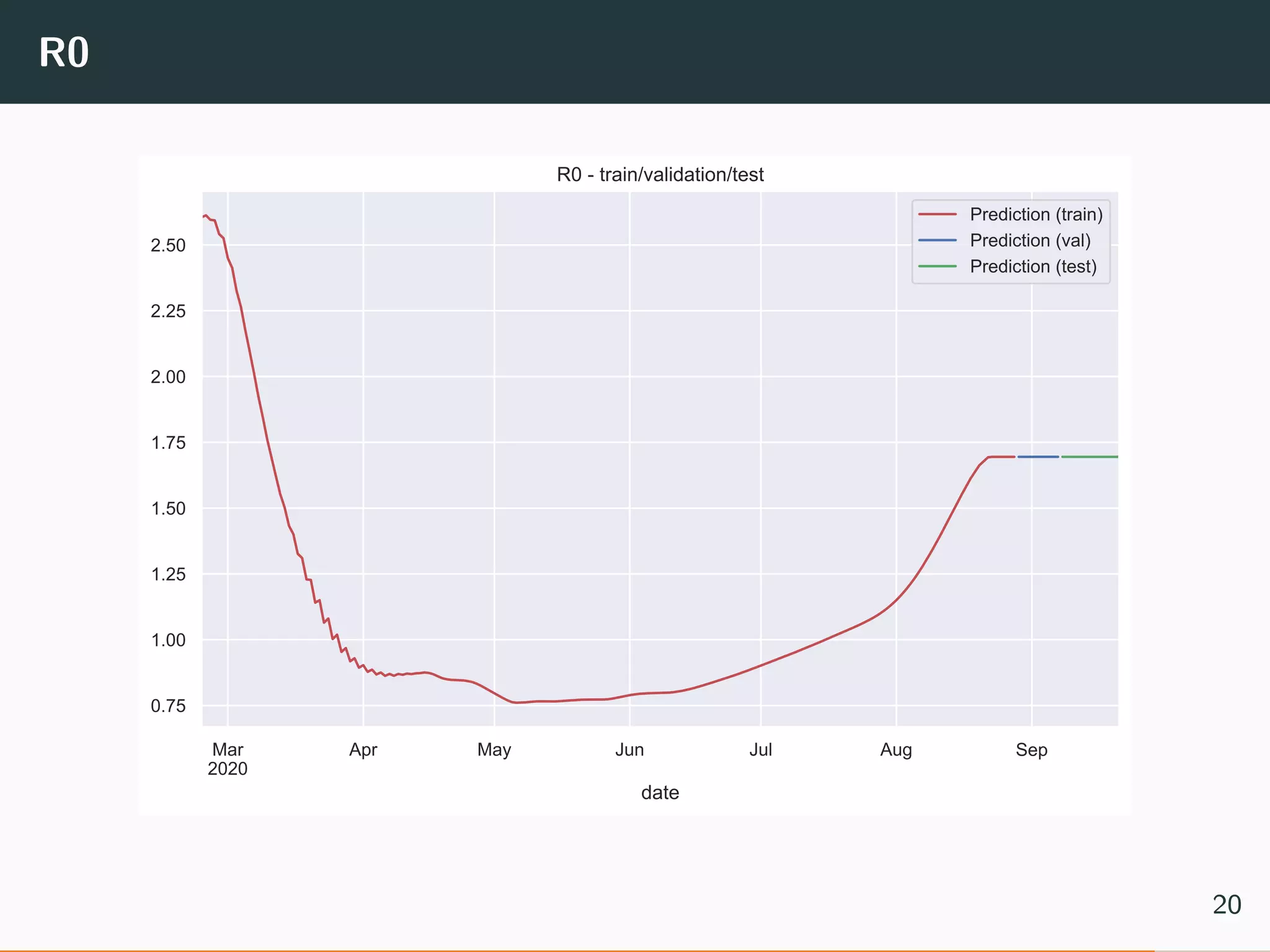

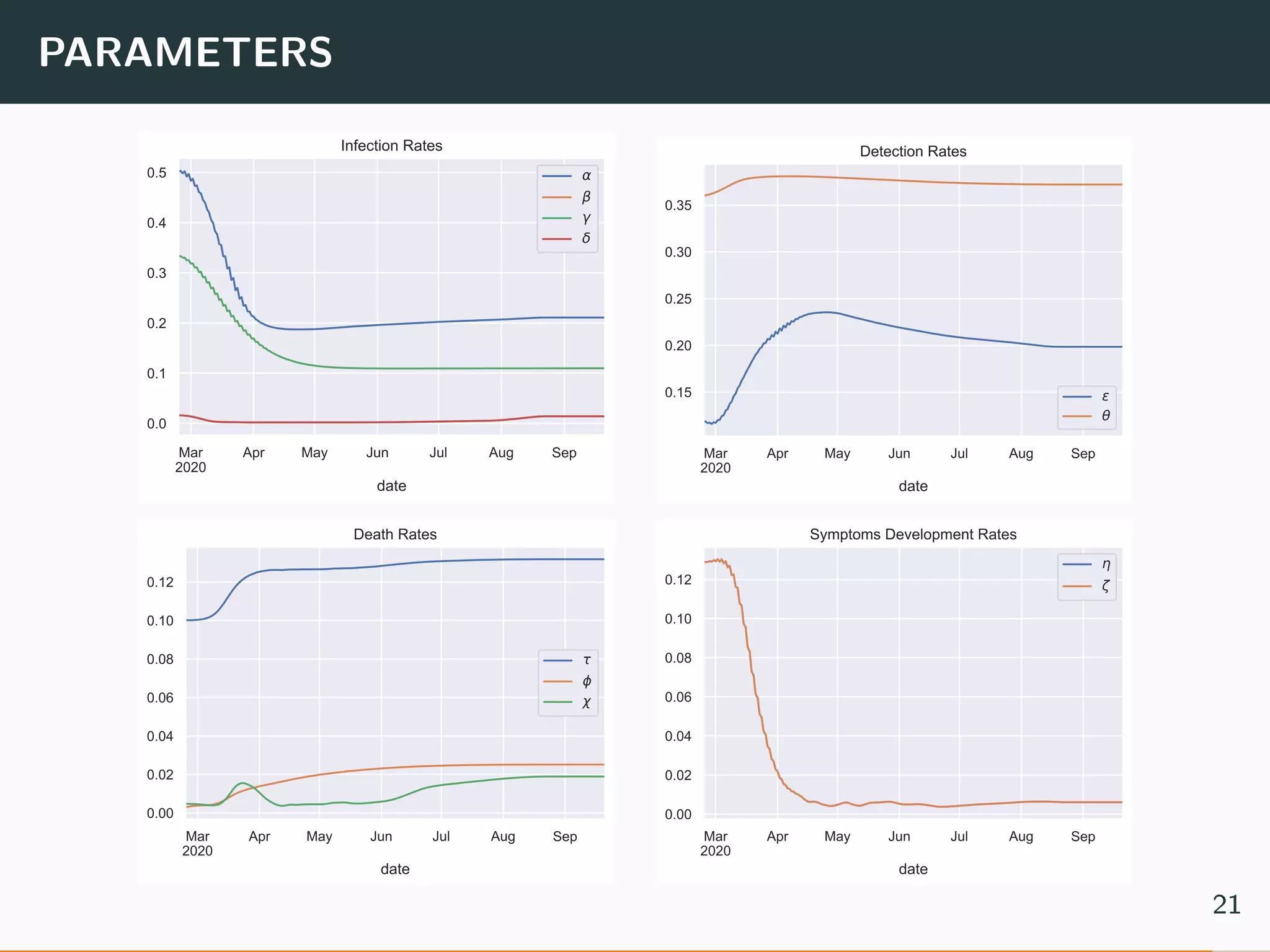

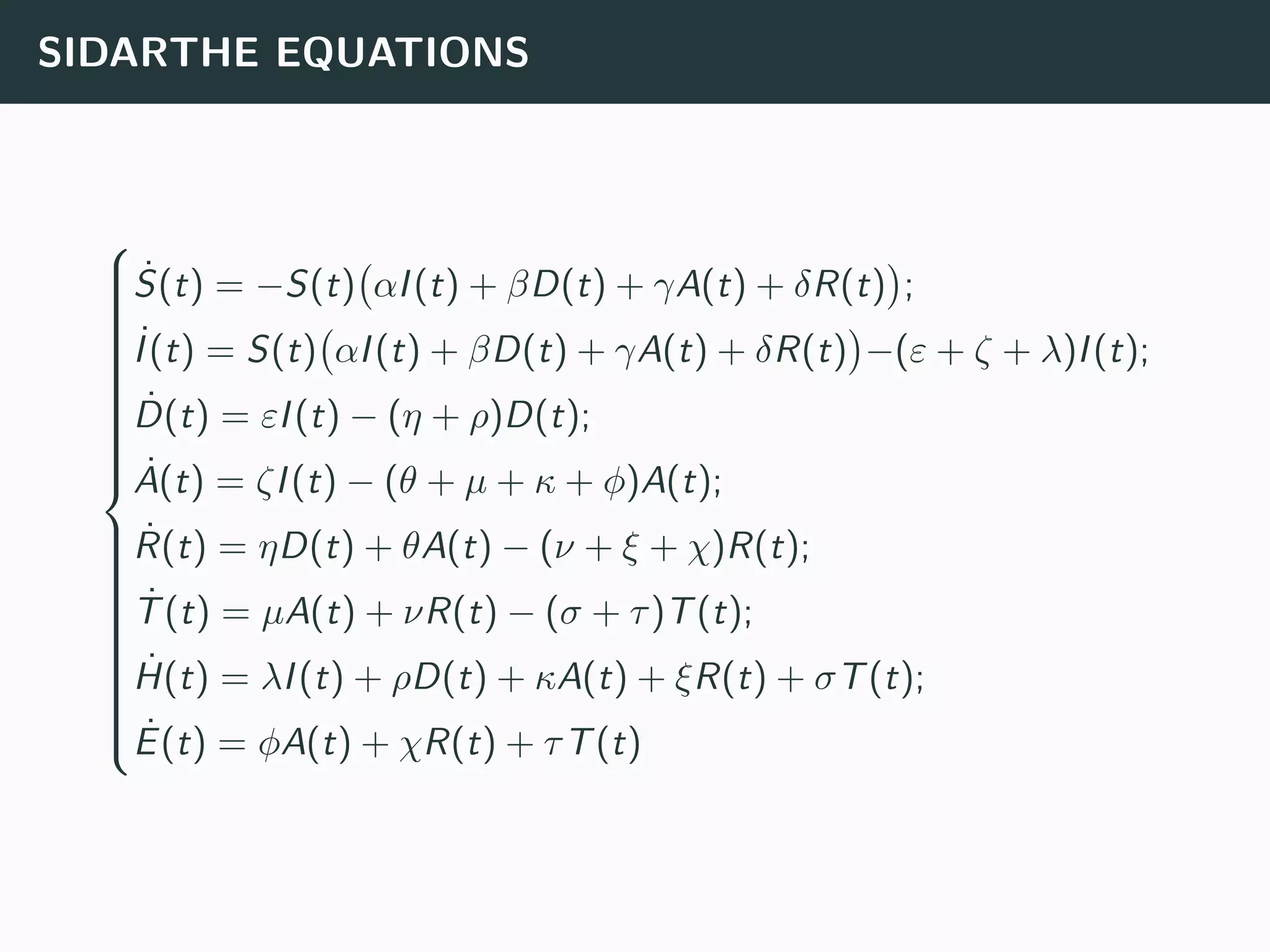

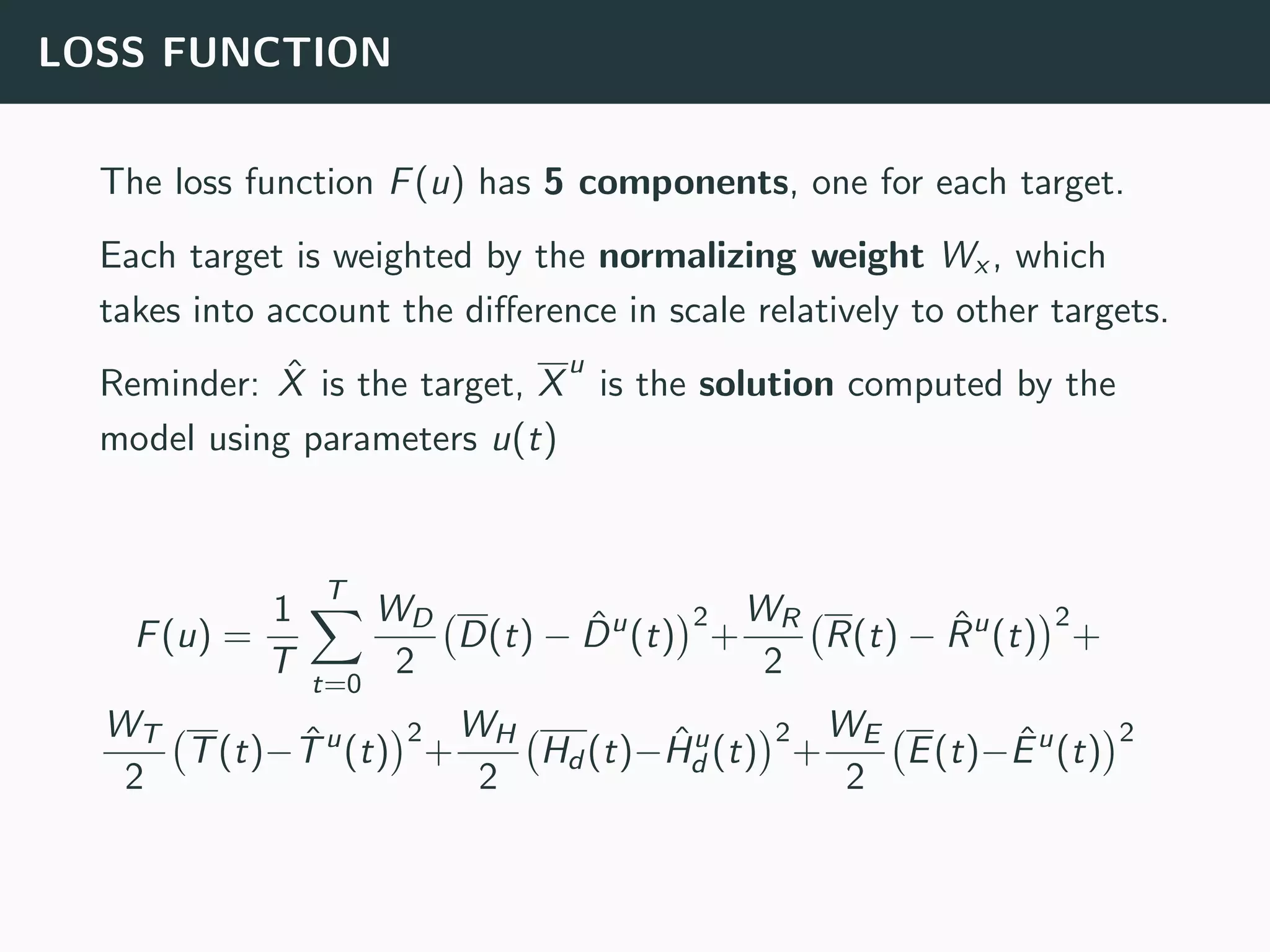

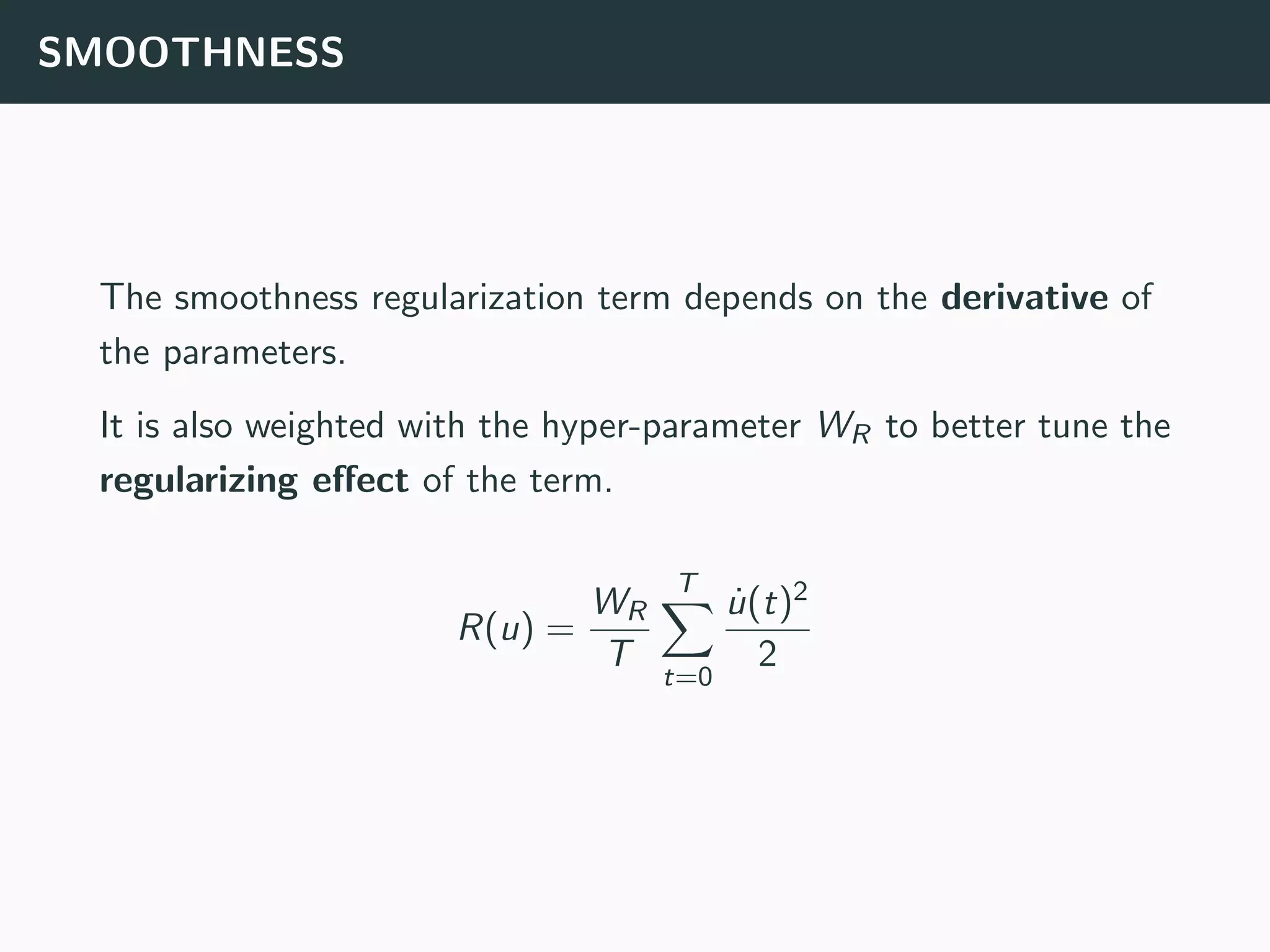

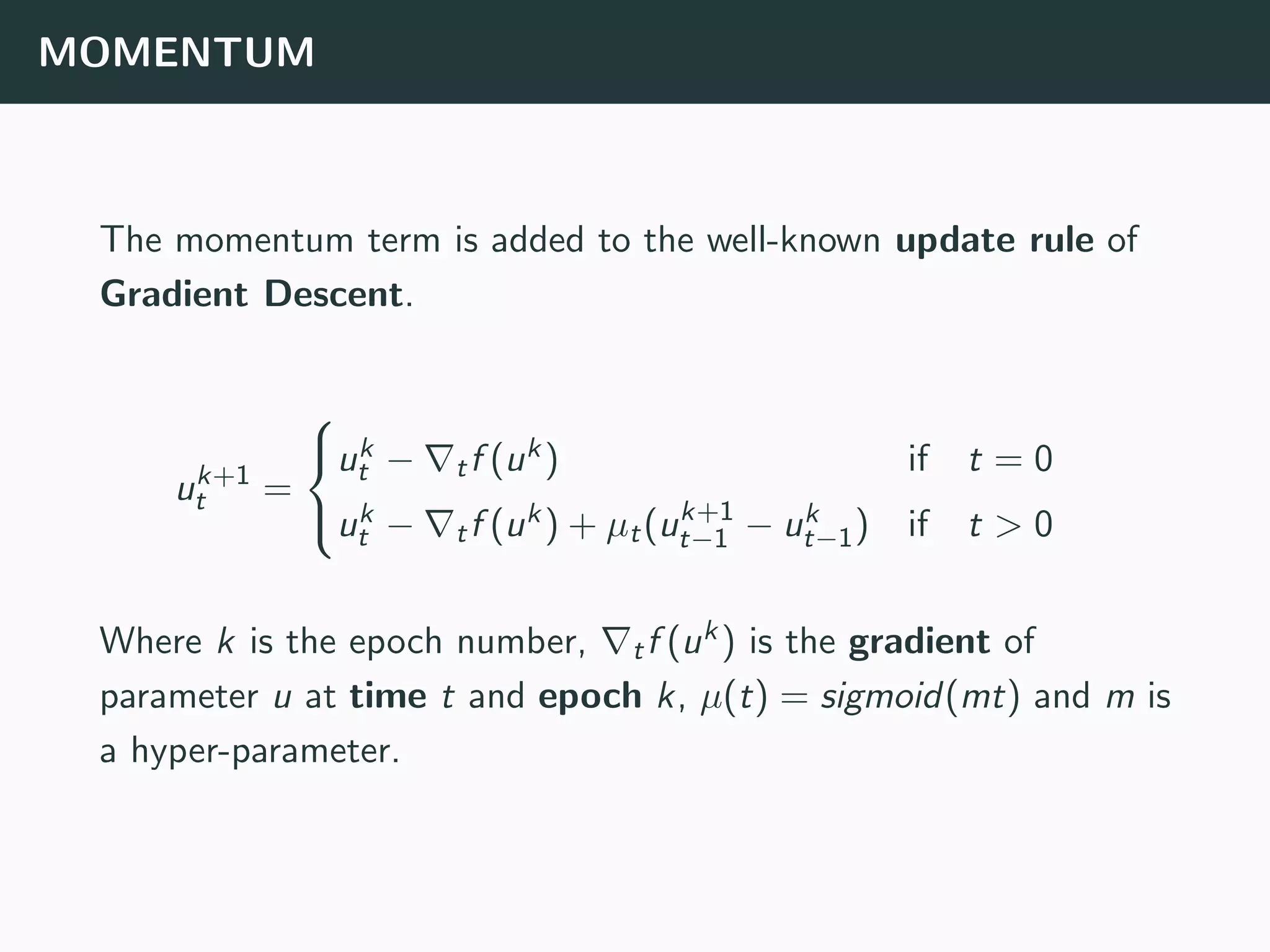

The document discusses the application of machine learning to epidemiological models, particularly in the context of COVID-19. It details the limitations of traditional deterministic models, favoring a more dynamic SIDARTHE model that accommodates time-varying parameters to capture the effects of public health interventions. The document also outlines methodologies for training and validating these models using extensive datasets to better predict the disease spread and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.