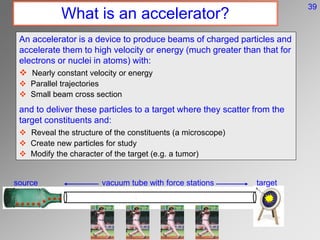

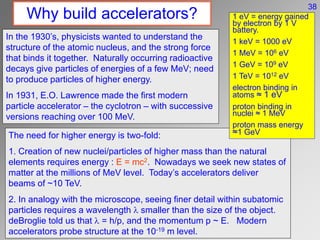

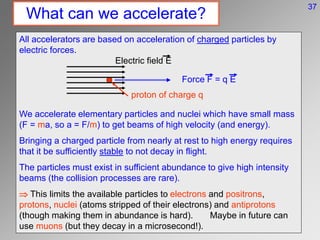

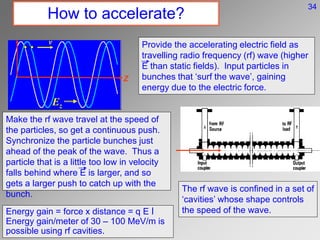

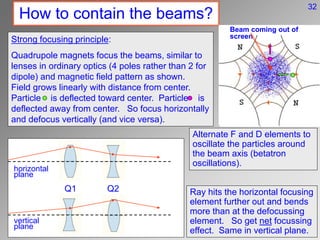

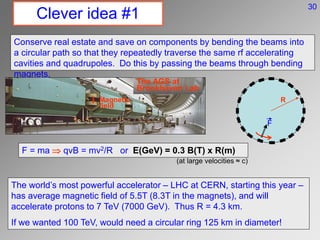

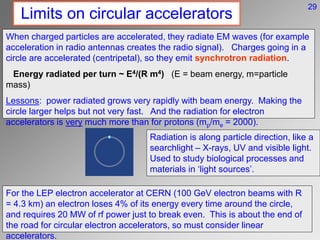

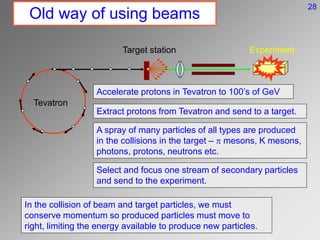

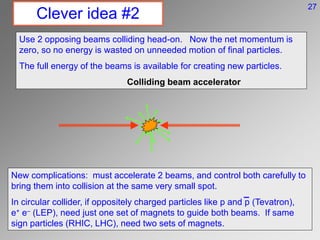

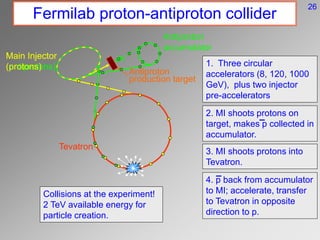

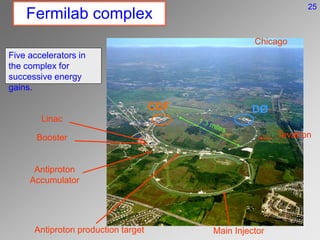

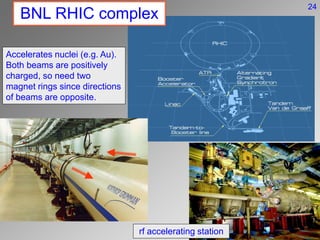

Particle accelerators use electromagnetic fields to accelerate charged particles like electrons and protons to high energies. They do this by using radio frequency cavities to impart energy to particle bunches, quadrupole magnets to focus the beams, and circular or linear designs. The highest energy particle colliders use opposing beams of particles and antimatter particles circulating in rings to study particle interactions at very high energies and reveal new insights into matter at the smallest scales.