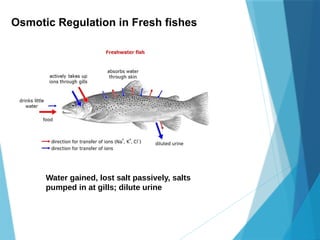

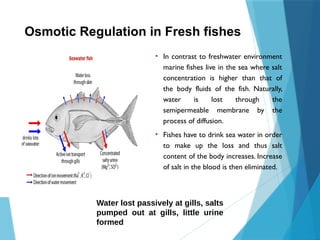

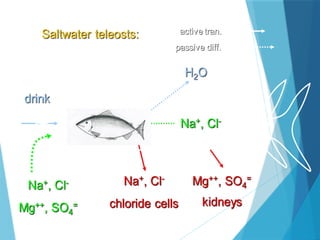

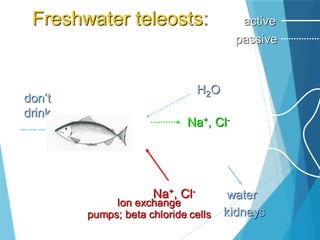

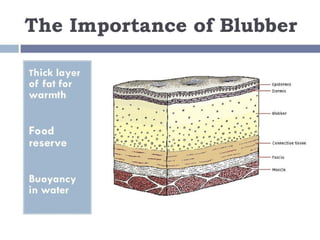

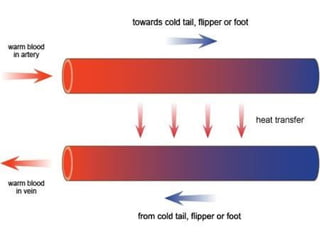

The document discusses various adaptations of aquatic organisms, focusing on how they evolve features to thrive in their respective habitats, particularly in freshwater and marine environments. It covers aspects of osmoregulation, thermoregulation, and specific adaptations such as streamlined bodies and specialized respiratory systems that allow marine mammals to survive in cold aquatic conditions. Additionally, it highlights the differences between freshwater and marine animals regarding osmotic strategies and adaptations to manage salinity levels.