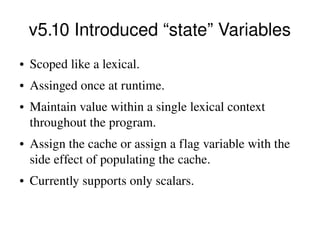

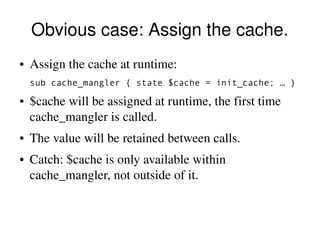

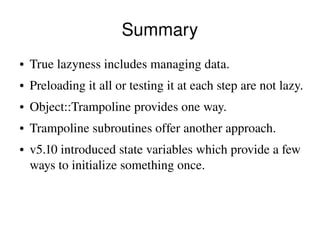

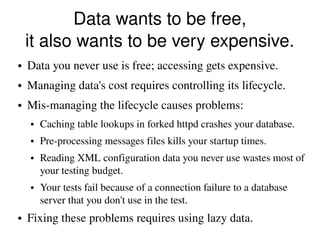

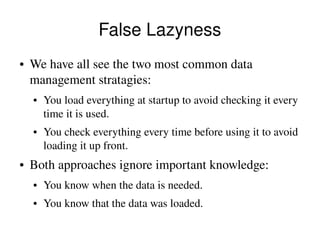

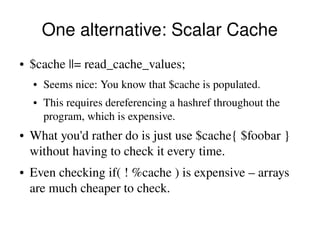

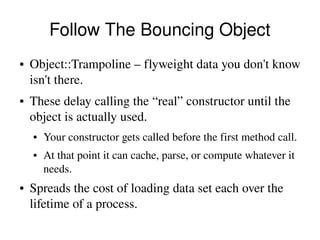

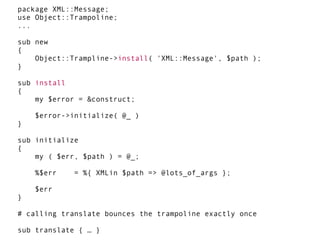

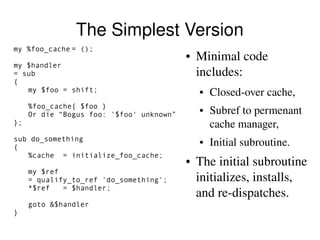

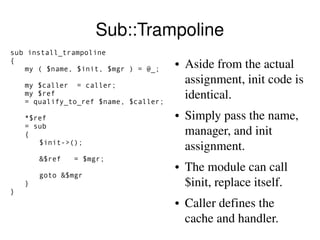

The document discusses the concept of 'true laziness' in data management, emphasizing the importance of loading data only when needed and maintaining its lifecycle to avoid expensive access issues. It introduces techniques such as trampoline objects, trampoline subroutines, and state variables from Perl v5.10, suggesting that these can efficiently manage caches and improve performance. Ultimately, the document critiques common strategies that mismanage data access and highlights the advantages of a lazy loading approach.

![BEGIN Blocks Are Cleaner

BEGIN

{

my $name = 'foo_handler'; ● The block isolates

my $ref = qualify_to_ref $name;

my %cache = (); cache, ref, and

my $handler sub variables;

= sub

{ allows recycling

%cache{ $_[0] } or die ...

}; the ref.

*$ref

= sub

● This is also rather

{

%cache = init_the_cache;

amenable to

*$ref = $handler;

installation by

module.

goto &$handler

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lazy-data-110703173127-phpapp01/85/Lazy-Data-Using-Perl-11-320.jpg)

![Using Sub::Trampoline

use Sub::Trampoline;

my %cache1 = ();

my @cache2 = ();

my $cache1_mgr

= sub { $cache1{ $_[0] } or croak "Unknown '$_[0]'" };

my $cache2_mgr

= sub { first { $_ eq $_[0] } @cache2 } };

my $init_cache1 = sub { %cache1 = select_from_hell }

sub init_cache2 { @cache2 = XMLin $nasty_messy_xml_struct }

install_trampoline( subone => $init_cache1, $cache1_mgr );

install_trampoline( known => &init_cache2, $cache2_mgr );

my $value1 = subone $key1;

if( known $value )

{ … }

else

{ carp “Unknown: '$value'” }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lazy-data-110703173127-phpapp01/85/Lazy-Data-Using-Perl-13-320.jpg)